20th September 2023

(updated 18/02/2024)

Preamble

On 20th September 2023, in celebration of its 100th year anniversary event, the Kuala Lumpur Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall (KLSCAH) organised a National Affairs Conference where the dons of the country’s politico-economics: Professor K.S. Jomo, Professor Edmund Terence Gomez and Dr. Muhammed Abdul Khalid expanded from their various academic papers to an audience of KLSCAH constituent members, the media and academia.

What were presented at the Conference have been explored in this site and exposed on other platforms, too; this essay shall tepidly traverse the geoeconomic landscape on an Madani economy Malaysia approach.

1] Neocolonialism to the emergence of Financialisation ethnocapitalism

Jomo began his presentation to articulate the existence of a neocolonial economy – whence 70% of national wealth was owned and controlled by foreign enterprises – at the time Malaya gained her independence to the present challenges in an era with the end of trade liberalisation under a Cold War 2.0 regime where countries have to remain steadfast to not only non-aligned but pacifists to the resonnance drums of war, and whence the state of a nation has to retain, and maintain, an economic nationalism in capital deployment and to privilige domestic investments than to rely on foreign direct investments (FDI), and whence the management of a national economy has to be of a more progressive role than to be dependent of The Triad monopoly-capital inflows to be captured by the technological elements of the infrastructural information systems platforms, (see Global Research, Sept 2023, G77 to reject digital monopolies; STORM March 2023, short-circuiting the rakyat; STORM January 2023, digitalisation-capitalism-and-smes) or even the Industrialisation 4.0 which the country does not have the process capacity nor the talented capability to attain those objectives.

Through the ownership and control of information, monopoly-capital dominates the digital capital, too. Capital accumulation permeates the entire production chain but through soft elements in the ownership of patents, copyrights, brands and logistical systems impoverishing the poors but enrich the bourgeoisie class by way of financialization capitalism. It was such that by the decade leading up to 2019, the largest 100 firms in the world had increased their total market capitalisation by US$12.7 trillion. A third of that increase (US$4.2 trillion) can be said to be accounted for by just seven firms: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft (the famous quintet ‘FAAAM’), Alibaba, and Tencent as enabled and enhanced by digital technologies:

In the country, there is a growing centralisation of political and economic power in the Office of the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance with a confluence of influence of the state over the GLCs that have the concentration of capital and accumulation of capital as Gomez laid out in Minister of Finance Incorporated: Ownership and Control of Corporate Malaysia, and more importantly, by offering higher dividend returns, cooperating closely with those local corporate capital that have connections to Global North monopoly-capitalists and through internationalising their operations, they successfully link up electrical and electronic small manufacturing enterprises (SME) with products assembly, supplies and logistics competitiveness into the Global North supply chains.

Some of the input to the local Digital Infrastructure or DI is the physical medium, the infrastructure through which the traffic generated by the internet flows. This includes everything from telephone wires, cables (including optic fiber and submarine cables) to microwaves, satellites, and mobile technology such as fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks, IoT, and servers as well. On the server-side, major companies like Amazon or Microsoft stepped in to build and provide this growing digital infrastructure known as “the cloud”. Besides cables, cloud, and other things mentioned above, the data centers (hardware and software) and their administration is also a part of wide digital infrastructure work; see STORM Feb. 2023, deepening infrastructural platforms stronghold.

The later stages of the New Economic Policy (NEP), as Gomez reiterated, only reinforced a government-intervened economy besides the emergence of monopoly financialisation capitalism with the formation of government-linked companies (GLCs), and kleptocracy within an entrenched ethnocapitalism environment that most of the time collaborated, and colluded, with Global North monopoly-capital – in an age of new economic imperialism, (Suwandi, 2018).

Thus, after gaining political independence, the economic state of a nation is still being dominated (45%) by foreign-owned enterprise; see Gomez’s last line bottom right column presentation slide above.

As an instance, M&E vendors like AIDA, SKF, Cohu, VAT, Oerlikon Balzers, Favelle Favco, Bromma, Vitrox, etc.; presently, Digi, Nestles and British American Tobacco are, by market capitalisation, leading the list of foreign companies that dominate the local businesses nowadays, see STORM 2021, Dominance of Financial-Monopoly Capitalism.

A TNC can be a 100% foreign-equity company; and there are over 5000 such sendiran berhad in the country, commanding an overarching external ownership and control of the national economy, (Charles Brophy, Ownership and control in 21st century Malaysia, newmandala, 17/01/2018; Puthucheary 1960) .

2] Shared Community Wealth or Poverty of a Nation

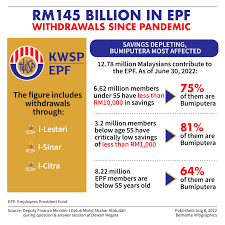

Khalid pointed out that with the wholesome withdrawal of the Employee’s Provident Fund (more than $145 Billion) during the Covid-19 pandemic.

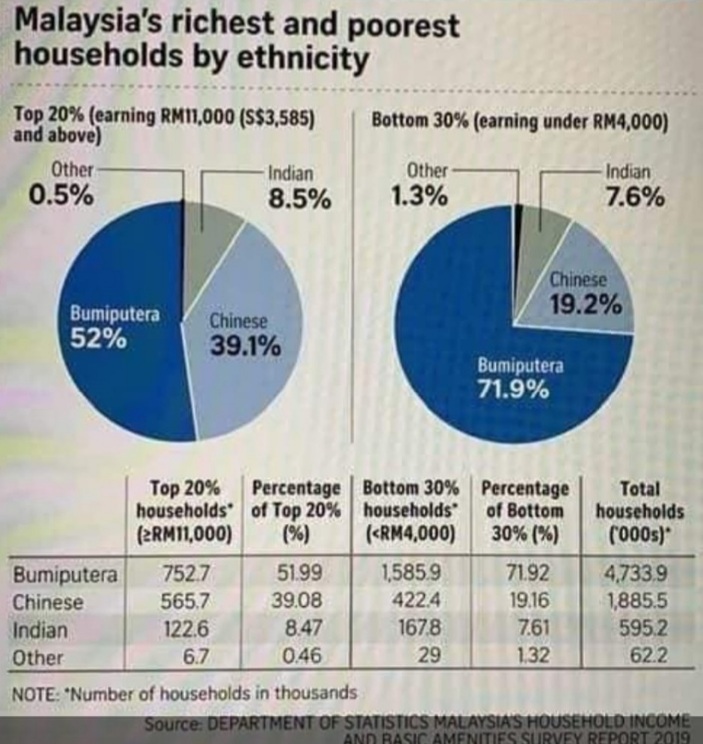

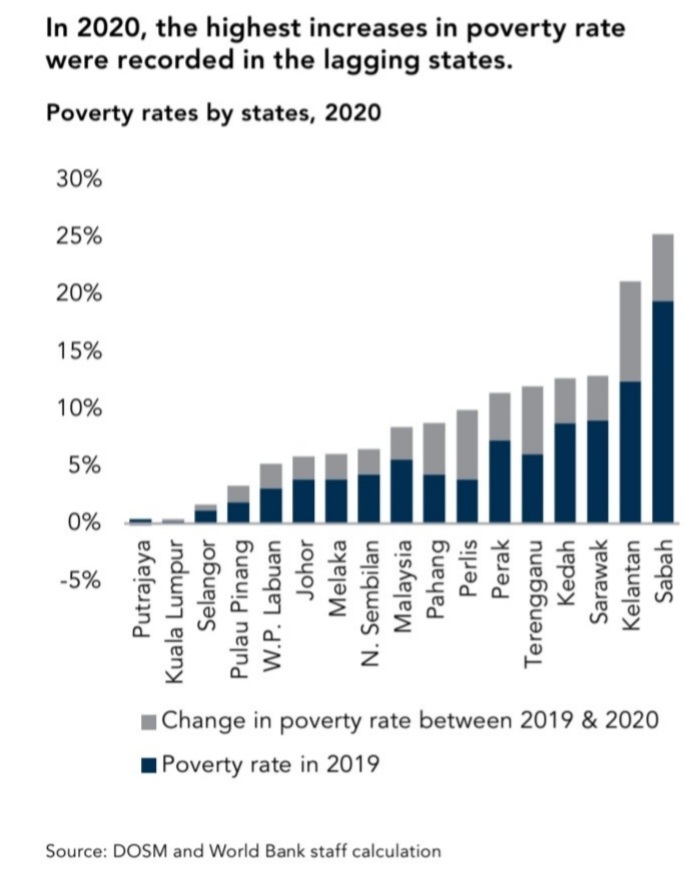

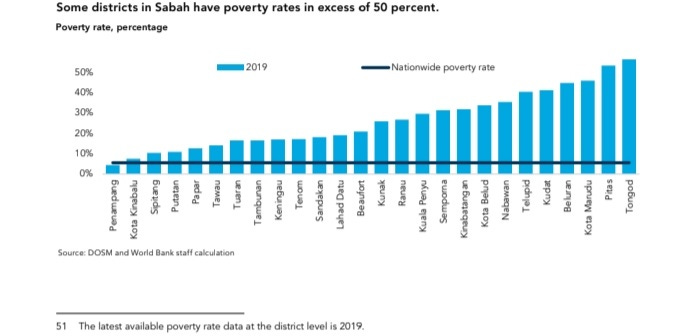

The country has more than 2 million below the poverty line, with Sarawak consisting 1 in 10 under the poverty line, Sabah the poorest state, and where the vulnerability is widespread because even in states like Selangor and Penang having 14% and 15% of their populace being in the poverty category.

The fact that many rakyat2 had not attained parity despite +60 years of neo-liberal enforced economic development is the existence of a new class of compradore capitalist nurtured by political elites.

It also come to pass that throughout Malaysia’s post-NEP economic history, and including the National Development Policy (NDP) (1990-2000) and National Vision Policy (2000-2010) – the inclusiveness agenda continues in the New Economic Model (2010-2020), where the policy goal is for Malaysia to become a high-income country by 2020 as well as sustainable and inclusive whereby the latter is defined as “enabling all communities to fully benefit from the wealth of the country” (National Economic Advisory Council, 2010) – the economic development processes have not bear out to support an equitable progressive domain.

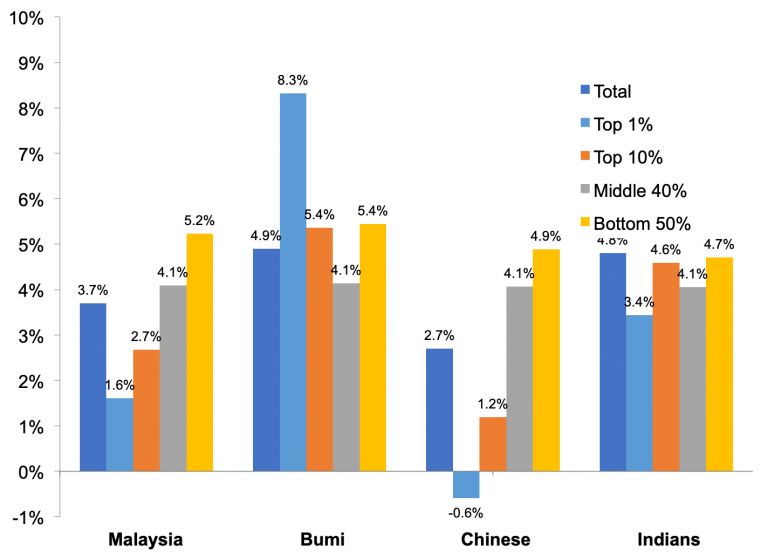

It has come to a situation where many a B20 malay child shall have only 1% of his/her generation peers being able to attain socio-economic mobility migration upwards; see Khalid lse research paper.

This economic nationalism posturing capriciously as affirmative action policy differs from those of other countries. It is “the politically dominant majority group which introduces preferential policies to raise its economic status as against that of an economically more advanced minorities“.

[see Puthucheary seminal work, written while in a prison, on the Ownership and Control of the Malaysian Economy, and the continuous in-depth studies by Gomez, with Jomo and Lim Mah Hui – collectively critical of selective privatisation and bumiputera equity quotas, and in the promotion of money politics that are acutely detrimental to national economic development; read also the 50 years NEO hasn’t worked and those articles in NLM#10.]

We are also at a juncture where the GLCs being money-suckling, their existence has had hindered the development of the true bumi enterpreneur class, as aspiring bumi enterpreneurs are either enticed into taking short cut to wealth through lucrative projects with high-priced and high-profit margins that inevitably in any long-term infrastructure project exhausted and expired them. However, once on board, very few bumi contractors would ever disembark from the enticing gravy train.

Any wonder then that despite 40-odd years of bumiputra policies and assistance to the bumis in the construction industry, there is not a single successful bumi contractor?

Ahmad Zaki Bhd, the most “successful” or prominent 100% bumi contractor listed on KLSE is on the verge of bankruptcy, while Panzana Enterprise SB a 35 years old 100% bumi contractor with good track records is in ICU after being stabbed in the back by Turnpike Synergy, a subsidiary of Prolintas which is 100% owned by PNB – a financial capitalism entity under a sovereign fund management.

3] The Challenges

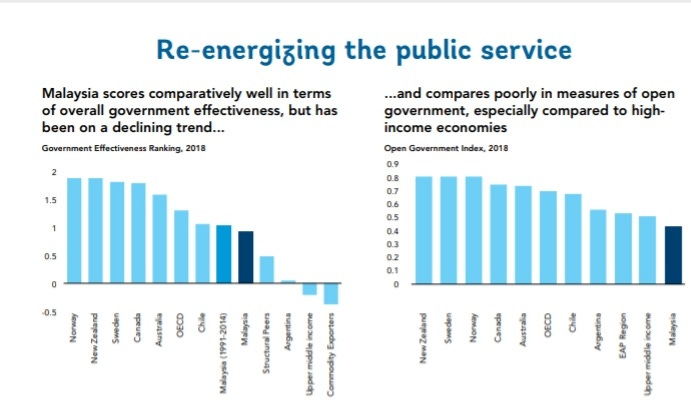

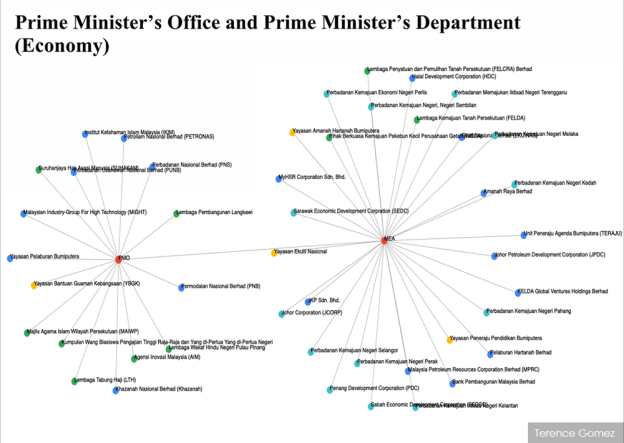

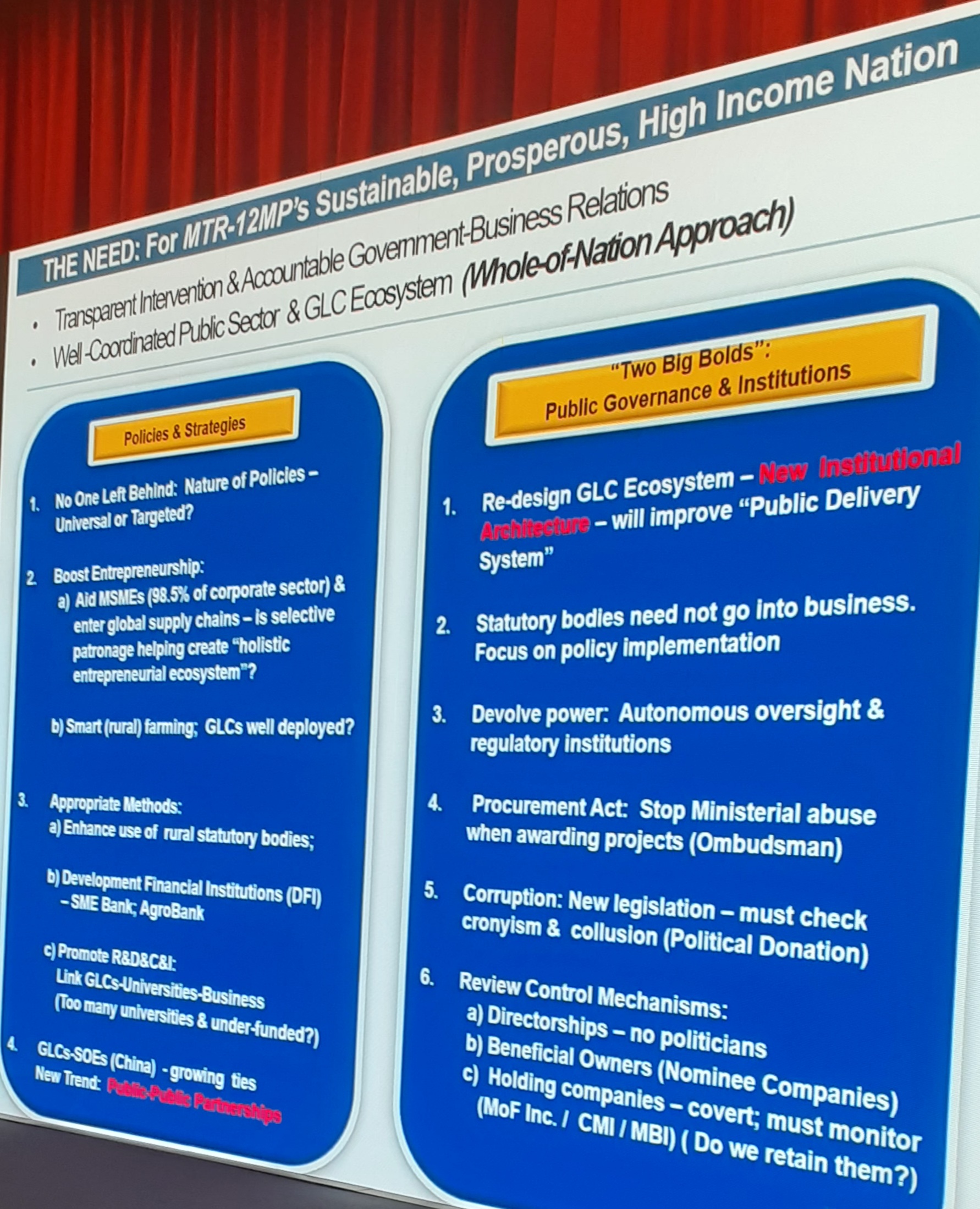

i) Gomez opined that one has to clean up the GLCs so that there is public governance without resource wastefulness, and to curb rampant corruption so that there would be no pandering to the political and capital powerful forces. Otherwise, as it is – the Ministry of Finance has hydra-like tentacles to own and control various types, categories and identities of GLCs entities.

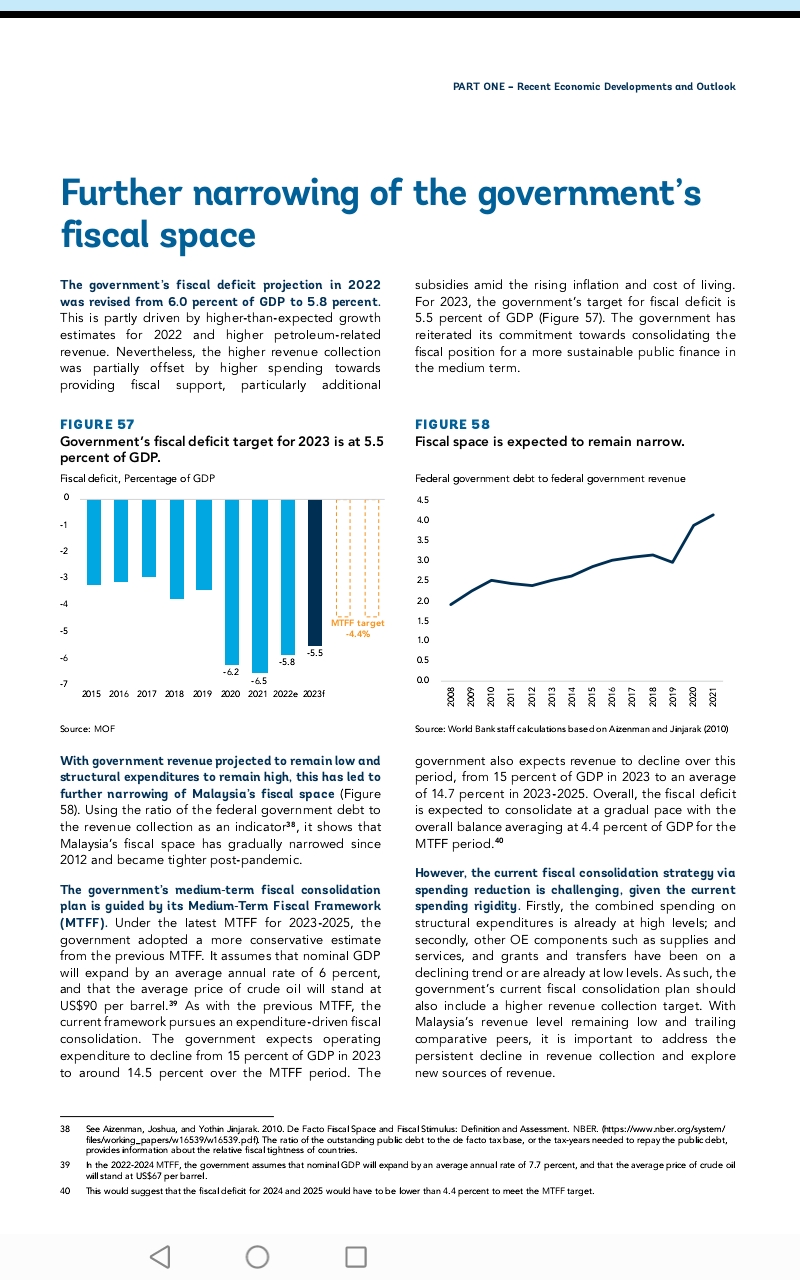

GLCs and GLICs (government-linked investment corporations) collectively controlled 68% of the Kuala Luimpur Stock Exchange: commanding more than RM$440 Billion in total assets. Further, this overwhelming overall control of government agencies and state corporations is connected to the Prime Minister Department and the Ministry of Finance :

ii) There is an existential need to protect the informal sector zero-hour labour where the social security elements should be holistically implemented to ensure a socio-economic wellbeing safety net rather than exploiting, and short-circuiting digital platform workers ;

iii) with the increasing cooperation between nation states, the public state corporations SOE-SOE relations need to be better redefined, and key actors must be held responsible otherwise ecological disasters will occur like the Melaka Gateway and Lynas rare-earth extractions pollution; see also Raub gold mining and Malmut copper mining.

iv) what new banking roles could be promoted by Bank Negara Malaysia as a banker intermediation between SMEs and the Big Bank which have a tendency to collarise transactions to the disadvantages of small firms, and where there is a powerful banker class attached to the financialisation capitalism in the country.

The financial oligarchs and capital rentiers are so dominant that it is truly an ethnocapital assertion in the national banking sector.

v) with an encirclement of China, an imminent US-CHINA conflict arising, (RAND Corp. 2021) in what ways would a pacifistic Non-Aligned posture shall position the country foreign affairs, and her foreign trade which contributed in 2022 140.75% to the gross domestic product has to be geostrategically assessed, too, especially with possibly decoupling and fractionalisation of global commodity chains.

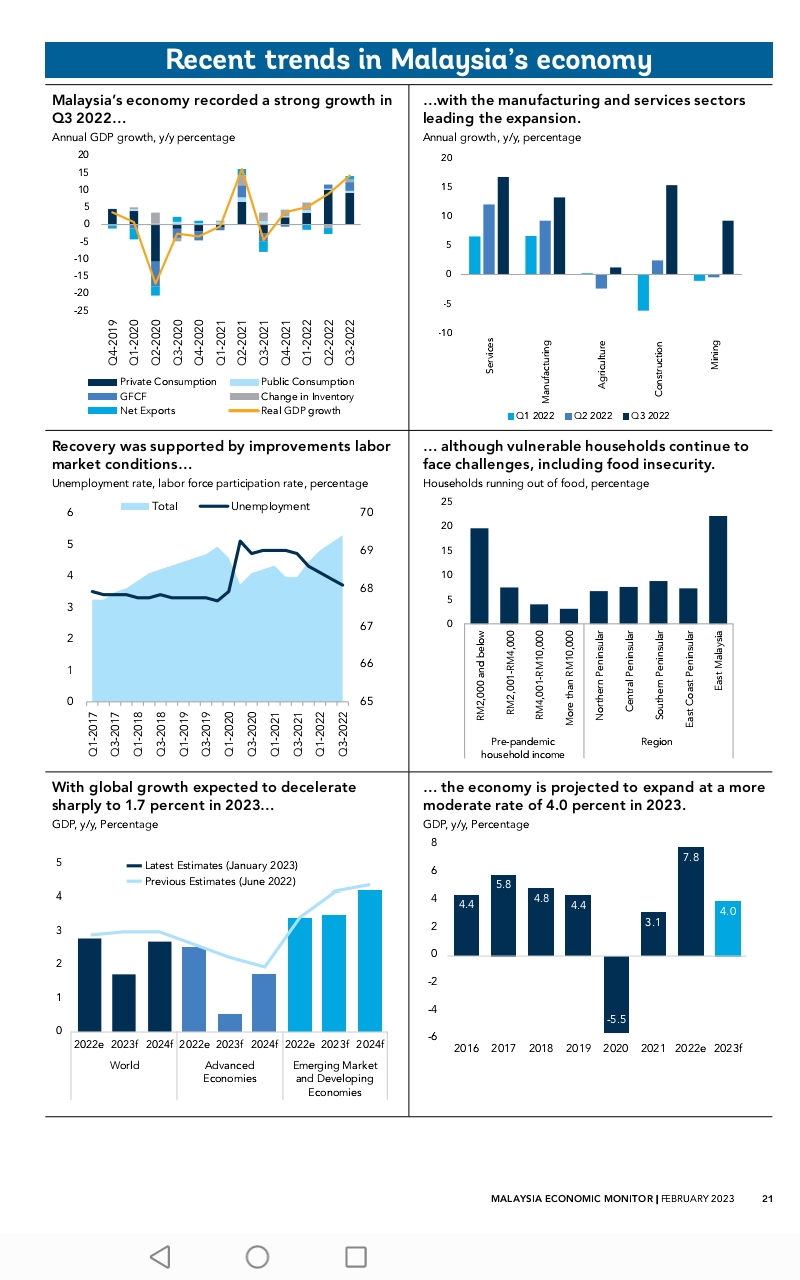

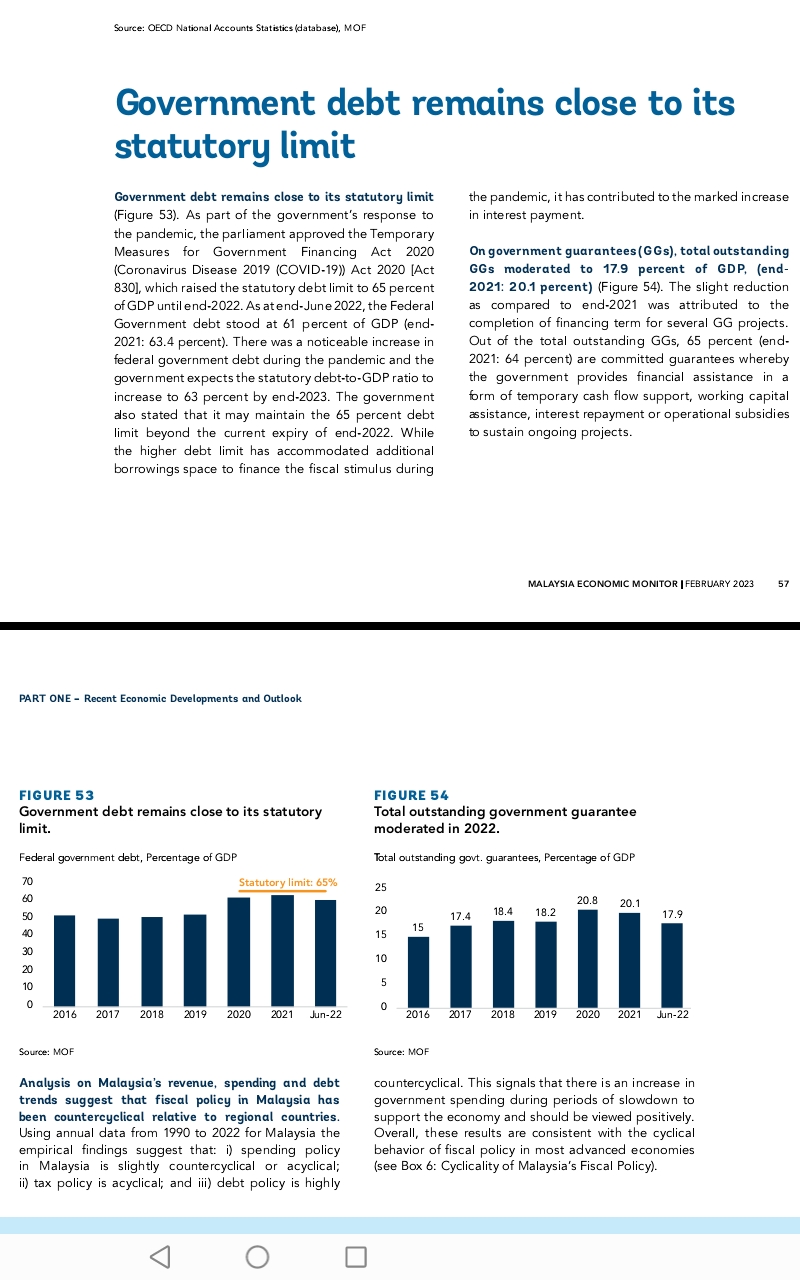

Indeed, it is also at a period when Malaysia’s economy only grew 3.7% in 2023, according to Bank Negara Malaysia data, coming in below the target of 4% to 5% due to “prolonged weakness” of external demand. The annual result was far off the 8.7% pace recorded for the previous year, (asia-nikkei, 16th. February 2024; as was concurred by AHAM Capital Malaysia.

EPILOGUE

We have come a long way from private enterprises to privatisation to GLCs in a capital-endowed environment that is no more than neoliberal policies with neoimperialism in context that indebted a nation in a dependency syndrome.

Can we do better?

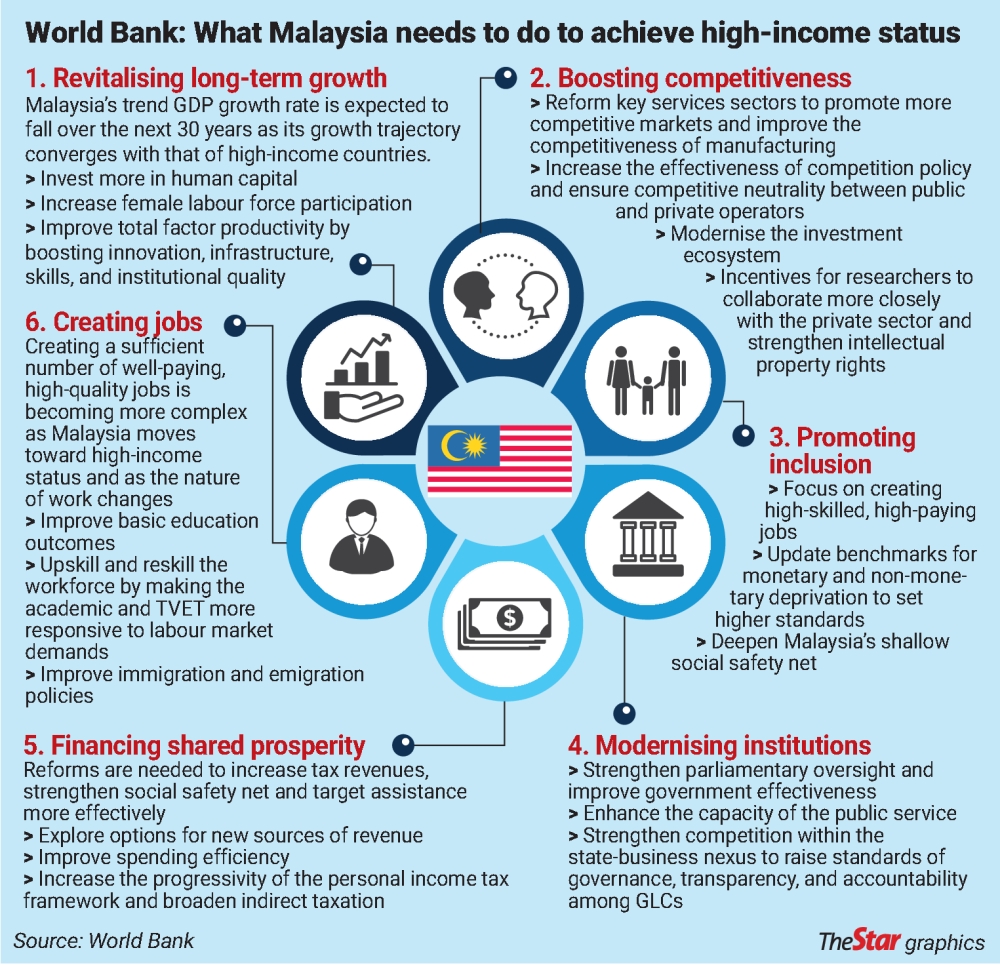

World Bank and DRC have identified the whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach in any economic development endeavour – and Malaysia has to do sama².

Long-term – strategically – we need to visionise on building communal organizations and governance to step onto a progressive path beyond capitalism and the capitalist state to TAPAO economic development and socioeconomic management, and towards a socialist undertaking that shall benefit everyone than the very few.

RELATED READINGS

The MADANI Economics Narrative

MADANI in a Defractionalised Geoeconomy

Madani Model towards economic development sustainability

PRAXIS with structural sustainability in economic development practices