1st August 2023

PREAMBLE

The cacophony on orchestrating the Madani Economic Narrative ( MEN) is overwhelming loud, with the Malaysia Institute of Economic Research (MIER) not likely to hold the baton too soon.

The symphony of disagreements on MEN has stretched from the theological aspect within a secular society (Bakri; Tajuddin; Hunter) with an uncertain economic Islamic impact upon non-muslims (Ignatius; Ramakrishnan), to the complications of managing complexity in developmental execution (UNICEF; World Bank, 2022; and World Bank, 2019); STORM; Ramesh Chander, Murray Hunter, and Lim Teck Ghee) while trying to achieve a post-ABIM script (Mohktar).

Whether the Madani precepts alone can serve as the pillars of a grand nation-building project when a rumah in a kampung built on a capital-muddied stilted foundation likely to collapse at any time under a neoliberalism policy regime, is due for a conversation.

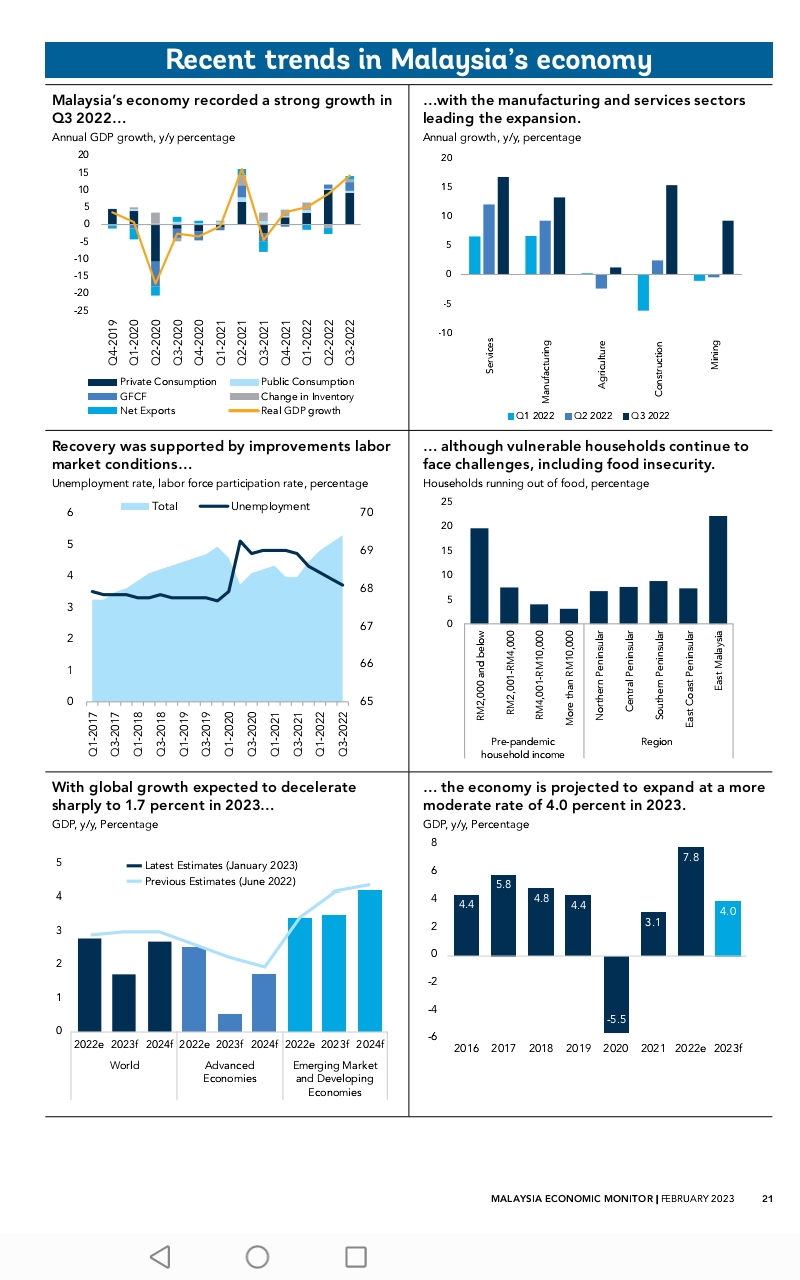

This is appropriate time because even an neoliberal institution – which was in the country prior to her independence as the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD precursor to the World Bank) – has once again expressed the multifaceted problems facing the economic state of a nation:

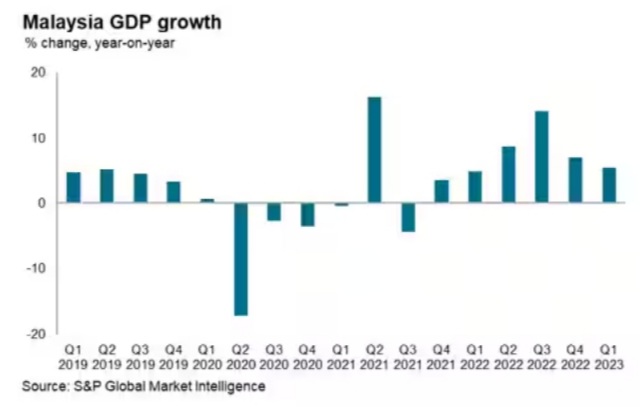

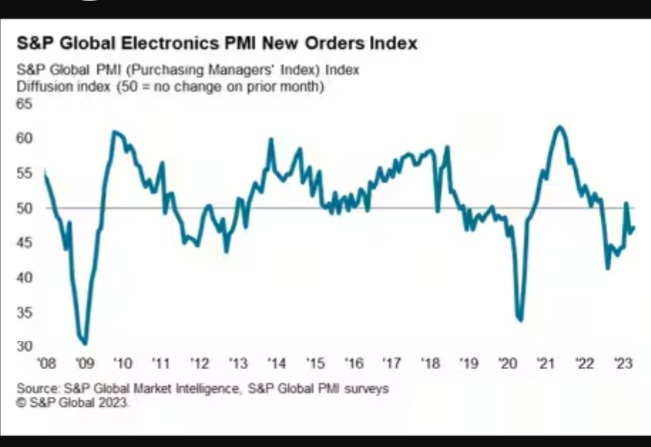

These uncomfortable situational conditions are further decimated by the MIDF Research data which maintained its forecast that Malaysia’s GDP growth will moderate at 4.2% in 2023 (2022: 8.7%), weighed down by uninspiring external trade performance as real export of goods is predicted to contract by 2.8% (2022: +11.1), reflecting weakness in regional and global demand.

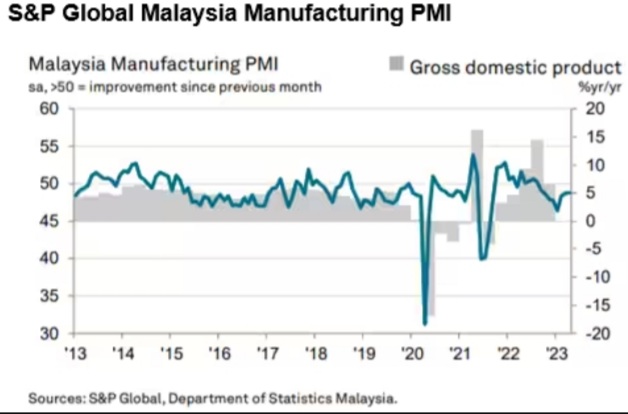

The 2nd August 2023 economic brief indicated that Malaysia’s S&P Global Manufacturing PMI recorded at 47.8 in July 2023 (June 2023: 47.7), marking 11 straight months of contraction which was mainly attributable to a significant dip in new orders, as demand has consecutively paced down for the last 11 months, (theedgemalaysia 2/8/23

I] THE POVERTY PROBLEMS

The successful implementation of Madani depends on reaching of targeted area poverty alleviation objectives (TAPAO) which shall rest upon the genre of structural changes to be adopted, the availability of debt financing in economic development, the wholeheartedly adherence to sound economic developmental praxis and a faithfulness to the core MADANI implementation principles

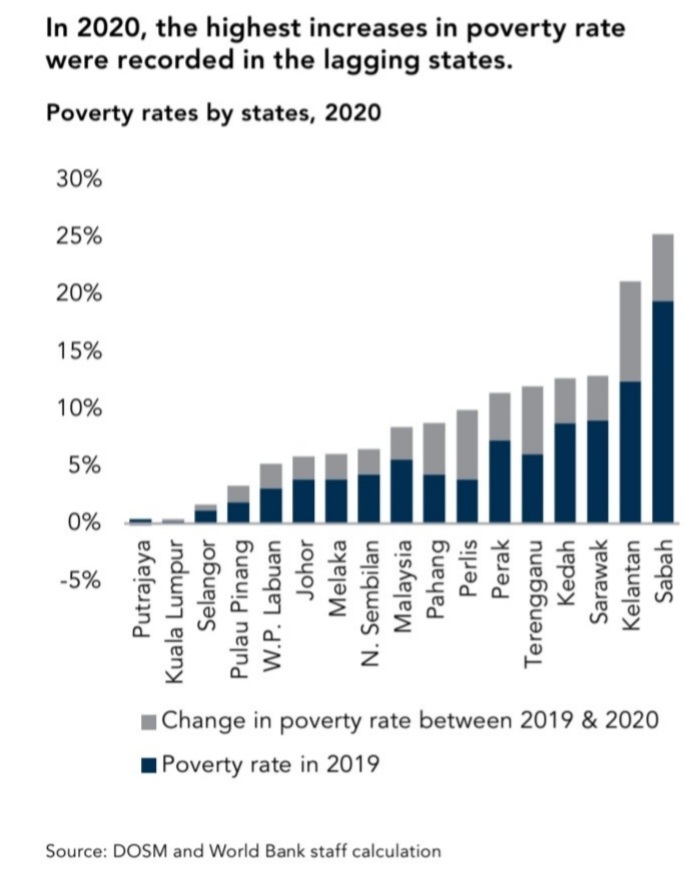

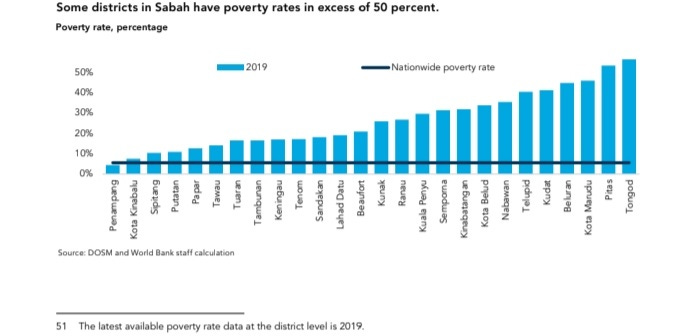

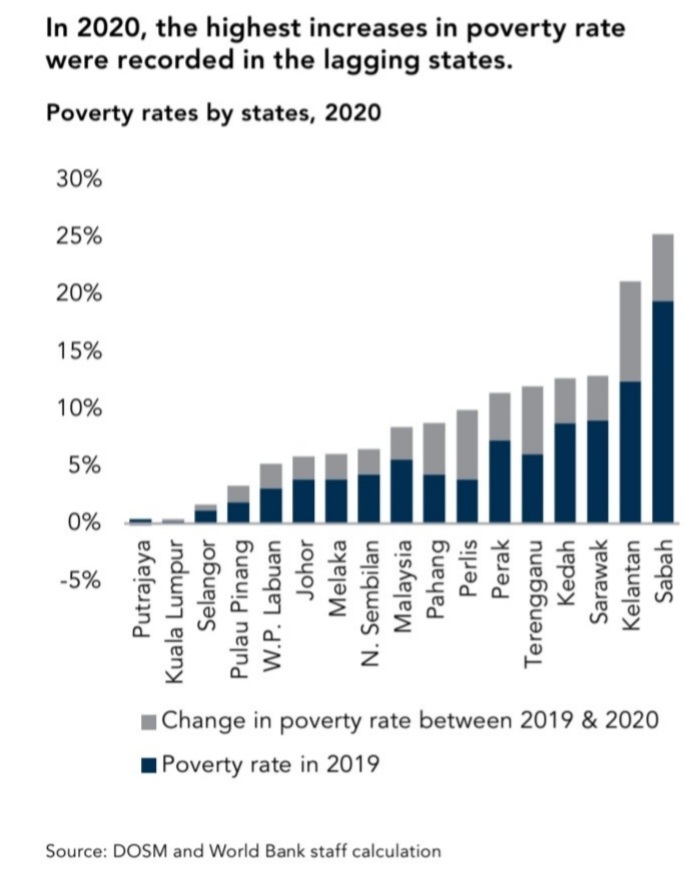

The Madani Challenges facing this state of nation were familiar issues covering +65 years in the development of underdevelopment of a nation where poverty, inequality, and marginalisation are predominant. As late as 2015, the Malaysia poverty rate was 4.80% which is the percentage of the population living on less than US$5.50 a day, (World Bank).

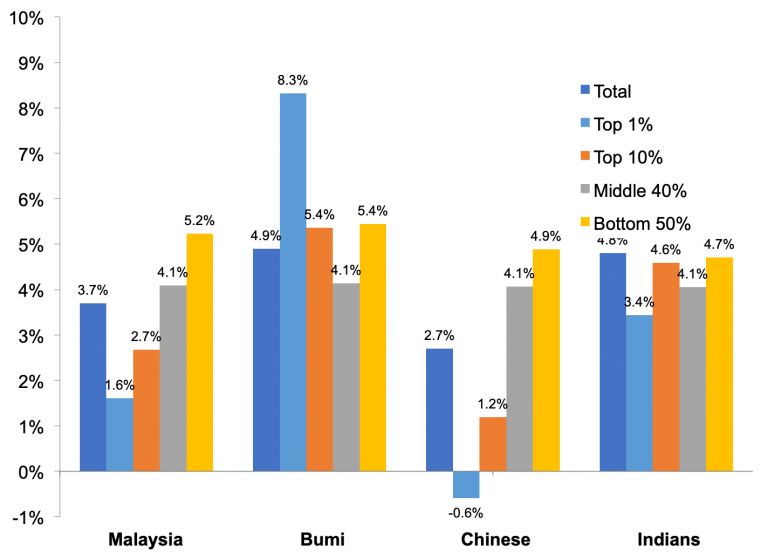

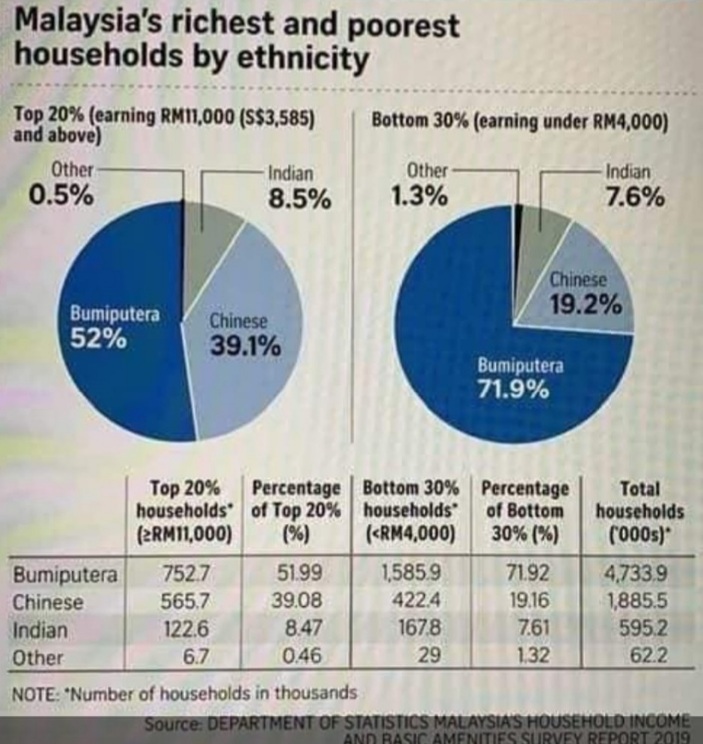

This is ardently expressed by Khalid research paper at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where presented, the disparity among the Malay community – the top 1% – is very much acute then as it is likely to be accentuated:

The most important implication is that although the middle 40 per cent and the bottom 50 per cent benefited significantly from economic growth, the Bumiputera in the top income groups (the top 1 per cent and the 10 per cent) benefited the most from economic growth. In sharp contrast, the income of the Chinese in the top income groups deteriorated. In a way, the strong growth in high-income Bumiputera occurred at the cost of a decrease in Chinese and the slow growth of Indians in the top income groups; Khalid, Income Inequality and Ethnic Cleavages in Malaysia: Evidence from Distributional National Accounts (1984-2014), World Inequality Database, working paper No. 2019/09.

The World Bank Report has this to say:

“The bulk of inequality today can be explained by differences in socio-economic factors within ethnic groups rather than differences across groups. It is time to bring all Malaysians within the ambit of greater economic opportunity.”

The need to update Malaysia’s inclusiveness strategies reflects both new realities and new challenges. The new reality is that poverty is no longer the key issue when thinking about inclusive growth. Poverty still exists—and pockets of poverty remain deep and concentrated—but inequality is now in the spotlight and is presenting a tremendous challenge. The other new reality is that inequality is no longer what it was four decades ago. Nowadays over 90 percent of the level of inequality is explained by differences within ethnic groups rather than differences between these groups. Individual socio-economic characteristics, such as activity status, sector of employment, urban versus rural stratum, and educational levels in different geographical locations are despairingly displayed.

II] REQUISITE STRUCTURAL CHANGES

This leads to the next step that demands structuring the economy for sustainable development.

To undertake this task, according to Philip Schellekens, lead author of the Malaysia Economic Monitor, (World Bank, 2010).

“The dual approach in the Economic Transformation Program of combining cross-cutting policies with private sector-led projects provides an excellent platform. The proof of the pudding, however, will be in the consistent execution of policy reforms,” he said. “Also, until solid implementation of policy reforms is seen there is unlikely to be a groundswell of positive sentiment of foreign investors towards Malaysia.” (World Bank 2010, ibid).

The November 2010 issue of the Malaysia Economic Monitor offered another analysis of where Malaysia is today and where it could go tomorrow by updating its inclusiveness strategies. “Our recommendations on this highly charged topic do not come out of the blue — they are based on a detailed analytical study of the latest household income, labour force, and enterprise surveys, which the authorities have made available to our team. We are also leveraging on the experiences of other countries around the world, who have addressed or are coping with similar challenges.”

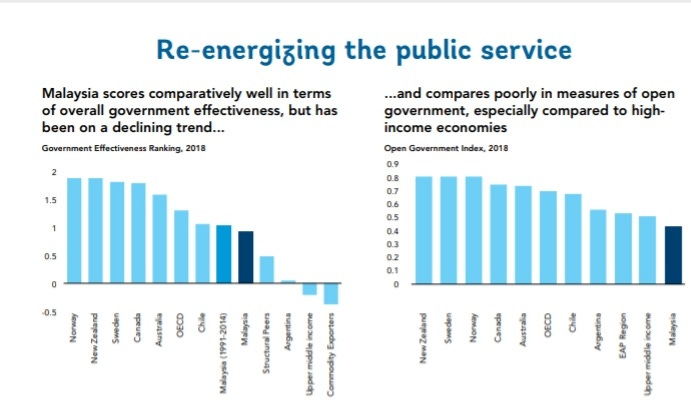

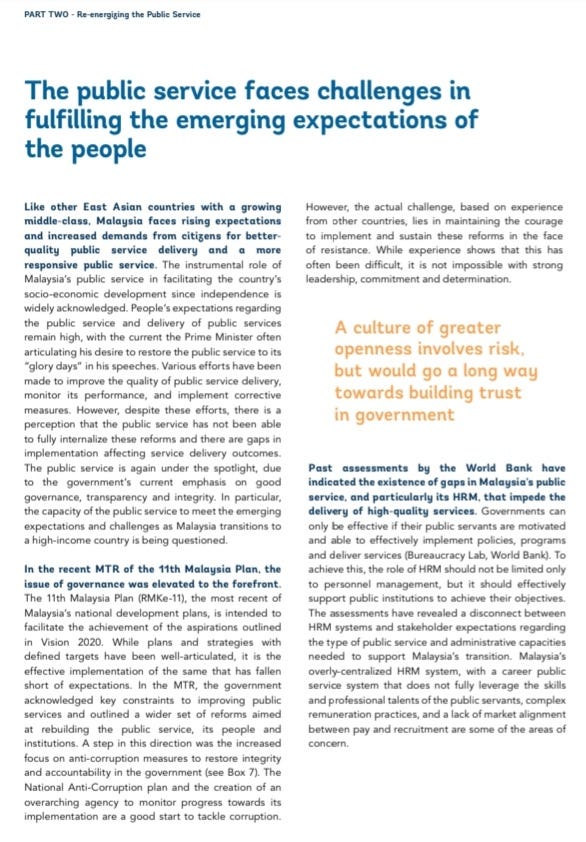

The implementation of an economic development plan requires the proficiency and professionalism of the public sector. This is where the effectiveness from the public service is under constant, and continuous, doubts.

At a time when the emoluments and the retirement charges of the public sector constitute 31.2% of the RM$372.340 million Budget 2023 announced on 7th. October, 2022 (which excludes contingency reserves yet-to-be disclosed) in the operating expenditure which are equivalent to the 32.8% of development expenditure for socio-economic programs and projects, including subsidies and social assistance – there is more than much concern on the performance and productivity of our civil servants whom,some alluded, to performing money-laundering.

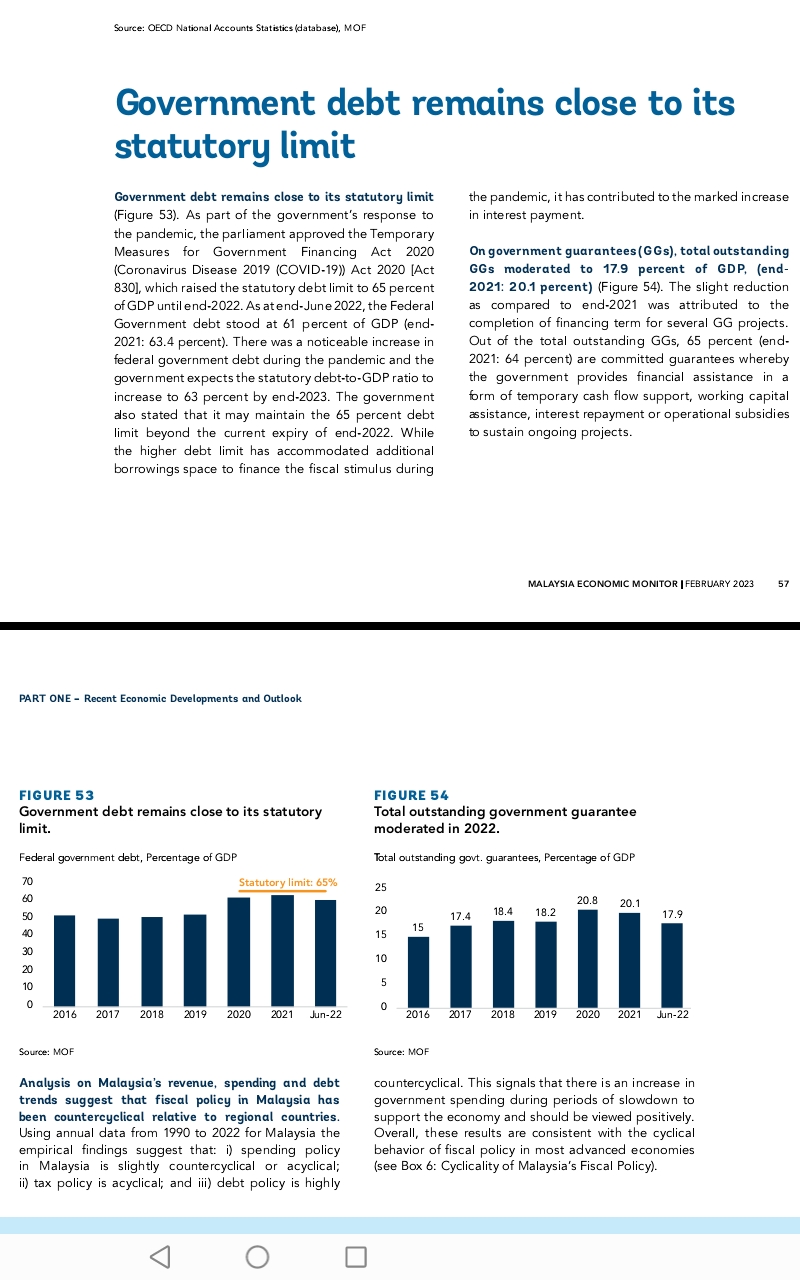

This is heading a grueling question on total government debt and liabilities as of June 2022 which is estimated to be at RM$1.42 trillion and will rise further; indeed, it was announced on 17th. January 2023 that the national debt including liabilities has reached RM$1.5 trillion. Total debt and liabilities are already 82 per cent of GDP, (read STORM October 2022, Underdevelopment of Development – consolidation of financial monopoly-capitalism).

As a share of revenue, a review done by the World Bank as far back as in 2011 has had found that Malaysia was spending about 27 percent of its revenues on salaries and wages/personal emoluments in 2009, significantly more than in some of the higher-income countries it aspires to emulate such as Canada (13.7 percent); Norway (12.5 percent); Australia (10.6 percent); and South Korea (9.6 percent).

In fact, by 2018, this percentage has increased to 34.3 percent for Malaysia, (see World Bank (2019). Malaysia Economic Monitor: Re-energizing the Public Service).

This is an extract from the World Bank 2019 Report on the challenges Malaysia has to confront to fulfill rakyat2 expections:

Can productivity performance objectives be executable or even achievable?

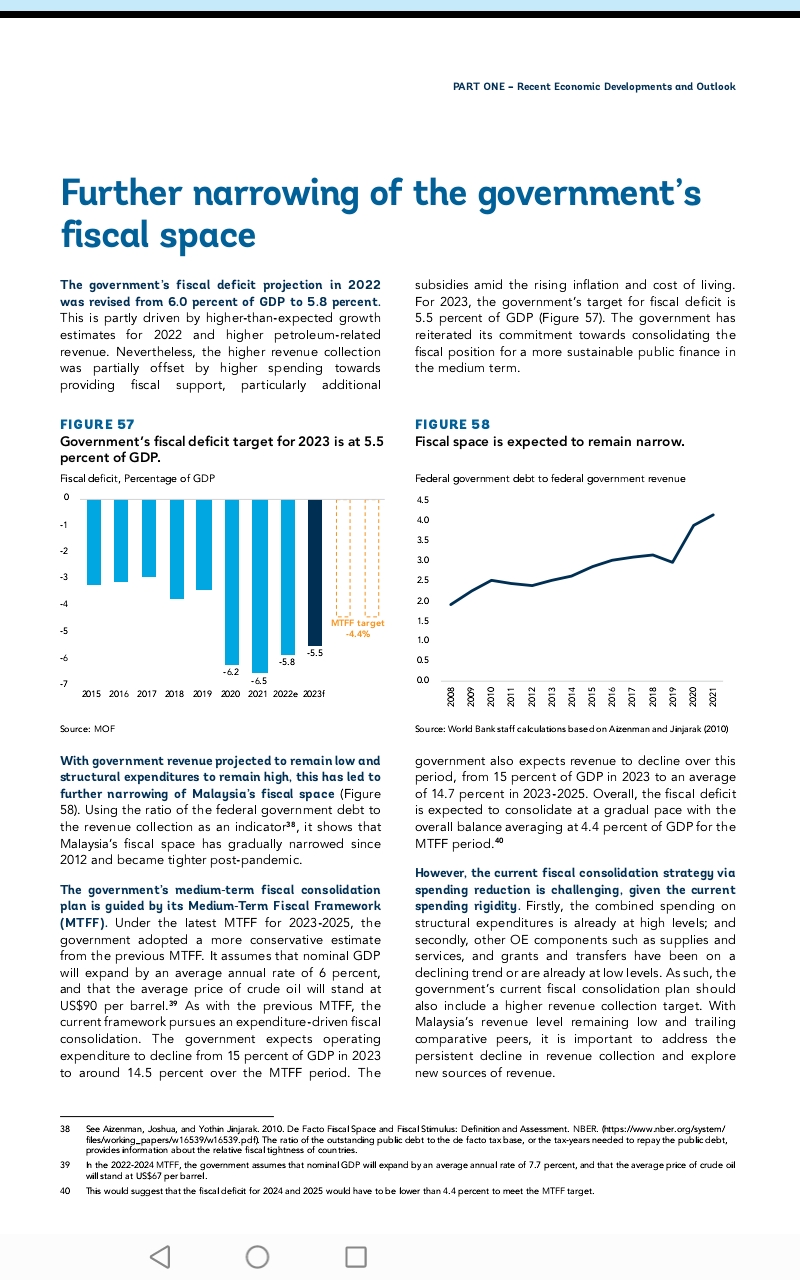

The second major restructuring requisite is the generation of government revenue to implement economic development programmes whilst supporting a top heavy, and inefficient, public sector – at a time when national fiscal revenue space is narrowing:

III] FINANCING ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

With those underlying facts, the key task is to source funds for economic development. This is well explored in (STORM 2023, Debt financing towards progressive economic path) where the nuances of the conversation are that since expenditures are already at high levels; and secondly, other operating expenditures components such as supplies and services, and grants and transfers have been on a declining trend or are already at low levels, therefore, the government’s current fiscal consolidation plan would have to include – besides restructuring Petronas, Khazanah and the GLCs -a higher revenue collection target that should coverage of a windfall tax on industries , according to Khazanah Research Institute senior advisor Professor Dr Jomo Kwame Sundaram.

“This is precisely the time when you must reform taxes as you have it (windfall tax) all the time amid extraordinarily high petroleum prices or palm oil prices.”

This is concurred by Institute of Malaysian and International Studies research fellow Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid who pointed out that policy-makers tend to ignore the imposition of capital gains tax when it comes to the issue of tax reform.

Even Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) assistant governor Dr Norhana Endut noted that the government’s tax collection capacity had not kept pace with the economic growth, at a time when the manufacturing sector is moderating on its p erformance:

IV] PRAXIS IN ECONOMIC REJUVENATION

The economic development of a nation demands that its goal to attain high-income and developed nation status while ensuring that shared prosperity is also sustainable.

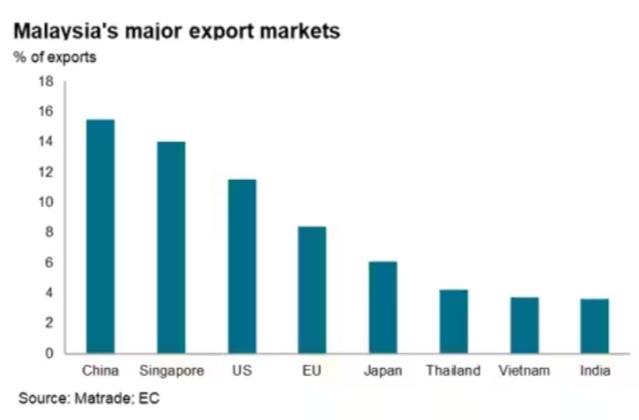

As one of the many Global South countries, Malaysia is one of the most open economies in the world with a trade to GDP ratio averaging over 130% since 2010. Openness to trade and investment has been instrumental in employment creation and income growth, with about 40% of jobs in Malaysia linked to export activities.

A government is always confronted with difficult decisions about appropriate measures under unforeseenable situations or in a crisis: what restrictions to impose and when to loosen them, where money will be spent and how it will be raised, and how to coordinate tasks between states and enable community cooperation.

These decisions have to take into account public health recommendations, economic considerations, and political constraints. Just as the policy responses varied – from the 2007–08 Global Financial Crisis, the dotcom 2002 burst and the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 – so do national policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic should differ for health, economic, and political reasons.

Play Politics

Why does the advice of independent consultants, analysts, and the academic go so often unheeded?

Political economy is about how politics affects the economy and the economy affects politics that Governments try to prime the economy before elections. However, business cycles are also creating ebbs and flows of economic activity and the circuitry of capital distribution around elections whence economic conditions have a powerful impact on elections. Politicians would manipulate these economic parameters to woo voters to gain political advantages, and contesting capital tries to support politicians.

Where are we now?

There is a cohort of powerful interests in favour of international trade and foreign investment. The world’s transnational corporations and international banks depend on an open flow of goods and capital. These are the monopoly-capitalists and the financial capitalists. This is especially the case today, when the world’s largest companies depend on complex global supply chains. A typical transnational corporation produces parts and components in dozens of countries, assembles them in dozens more, and sells the final products everywhere. Trade tariffs create barriers with these supply chains, thus the world’s largest companies are biggest supporters of freer trade.

That is why there is a need for perpetuating the mass of special and general interests in society so that these social institutions play a major role in national policymaking. The ways in which societies organize themselves – through and by economic sector, ethnicity, and importantly at this juncture of our political awareness, the class factor, shall affect how we would like to restructure our politics.

Definitely, political institutions have to mediate the pressures constituents bring to bear on them; even oligarch rulers have to pay attention to at least some part of public opinion. Political economists call this the “selectorate,” that portion of the population that matters to policymakers. In an authoritarian regime, this could be an economic elites or the ruling class or the armed forces. In an electoral democracy it would be voters and interest groups. No matter who matters, policymakers need rakyat2 support to stay in office.

In building an equity society with socialism as the dominant foundation, we must do all we can to develop the productive forces and gradually eliminate poverty, constantly raising the people’s living standards. Only when this outcome is achieved and there is significant prosperity for all will it become possible to begin the shift to advanced stage of an economy that is highly developed and where there is overwhelming material abundance. Only by this process that we shall be able to apply the principle of from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

To achieve this process, there is a need on genuine planning and genuine democracy where these are through the constitution of power from the bottom of society. It is only in this way that a progressive socioeconomic society, and its healthy and well-being domain, becomes irreversible.

Towards this process in striving the Socialism with Malaysian characteristics goal, there shall be a combination of planning and markets forming the basic socialist economic system. Second, we need to keep in mind the dialectical relation between ownership and the liberation of the productive forces that shall entail, then

(1) the system contains a multiplicity of components, but public ownership remains the core economic driver, with corporate capitals supplementing capital formation but without undue surplus value extracted from labour;

(2) while both state owned and private enterprises must be viable, their main objective is not profit at all costs, but social benefit that meets ‘people-centred’ needs from appropriate shelter, education equity to community-base healthcare, harnessing modern technologies towards social needs;

(3) it employs the primary socialist principle of from each according to ability and to each according to work, limiting exploitation and wealth polarisation, and ensuring common prosperity and wealth sharing for every rakyat2 wellbeing;

(4) the primary value should always be ‘socialist collectivism’ – gotong royong community-based than bourgeois individualism and inflicted neoliberalism ethos.

Therefore, as applied under a TAPAO approach, it would be sizing and averaging rural per capita income besides focusing on the country’s hinterlands, especially the mountainous interiors of Sarawak and Sabah.

Refining the geographical target of poverty reduction programs is a necessity. The TAPAO needs to shift from daerah² to kampung² including more likely

some outside the list of poverty-stricken daerah, too. Collectively, those designated kampung² (villages) may cover

a certain high percent of the country’s rural poor. Designated villages could then apply for projects to support local production and infrastructure (including makan-pada-kerja : food-for-work programs, worker training, and agribusiness development comprising technology extension services; not to be neglected, government-linked investments in social infrastructure (schools, clinics, community and recreation centers), with a particular strong participatory community-based self-help gotong-royong approach.

V] MADANI IMPLEMENTATION PRINCIPLES

For the SCRIPT in Madani Malaysia to be successful, in term of implementation and sustainability of a progressive politico-economic developmental praxis, working-class unity has to be consolidated.

It can only be further solidified if the tenet of divisive divisions by capitalism is better understood both in theory and in practice. Hence, we argue for a comprehensive yet bold project that is based on TAPAO that goes beyond its ethos as a renewal of an socialist ideal with Malaysian characteristics in order to take full account of the struggle of the labour movement.

Within the context of Malaysia development of underdevelopment – glaringly as in the cases of northeastern states in semanjung and the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak, and the many urban poors in the country as documented by the World Bank and UNICEF, we are witnessing the relational inequality generated. This is further reproduced by labour superexploitation and relational surplus value whence labour superexploitation is the essence of capitalism as neoliberalism is imperialism, too.

For Malaysia politico-economic model to be successful, and sustainable, the core issue of contradiction between capital and labour needs to be resolved with a Madani trustful outreach.

More so, after ethnocapital has owned, controlling and dominated the Malaysia resources, it is appropriate period of a new era under an unity governance to present a new narrative on Malaysian labour working cohesively and collaboratively – at this particular junction of a historical period – with capital to a shared prosperity domain under a common wealth practice for labour, too.

For one main obvious reality of capitalism is that massive poverty across the Global South is not the result of some local insufficiency (resources or skill talent) but rather due to the functioning of neocolonialism perpertuated by liberal economic policies as neoimperialism where the ongoing effects of dependency on financialisation capitalism need to be tamed.

The haemorrhage to present economy is the resulting outcome of those extractive institutional forces since post-independence, accelerated by succeeding regimes in governance with odious practices, and as articulated by Prof Kamal Hassan in Corruption and Hypocrisy in Malay Muslim Politics while Khalid’s London School of Economics and Political Science research has pinpointed the class structure-laden beneficiaries to their enduring enterprises.

The trust between labour and capital has to be firmed up solidly in fulfillment of a Madani Malaysia – more so when 98.5% of businesses are the SMEs contributing 36% of the national GDP where labour is important as capital because it provides employment for 7.3 million people – nearly half of the country’s workforce.

EPILOGUE

In short, we need to modify, adapt, and contextualize a conversation with our preceding political-economic reform agenda, and while trying to calibrate the sequence of, and the dimensions for, economic reforms – we seek to ask the pertinent question: have we really restructured the stagnated, and a doomed, national economy, ever ?

We need to be in the threshold of a new sovereignty re-imaging a New Malaysia positioning an entity adhering a New Narrative to perform New Politics for the generasi muda.

RELATED READINGS

Renewal of the Socialist Ideal