Collective on Geoeconomics

28th February 2023

For a long time it seems – more than two decades – since Olin Liu’s IMF Report is there a structural approach to national economic development that is more strategic and formative in dealing with politico-economic realities faced by the nation in totality.

An analysis on a previous attempt in structural reform under a stagnated economy was explored HERE.

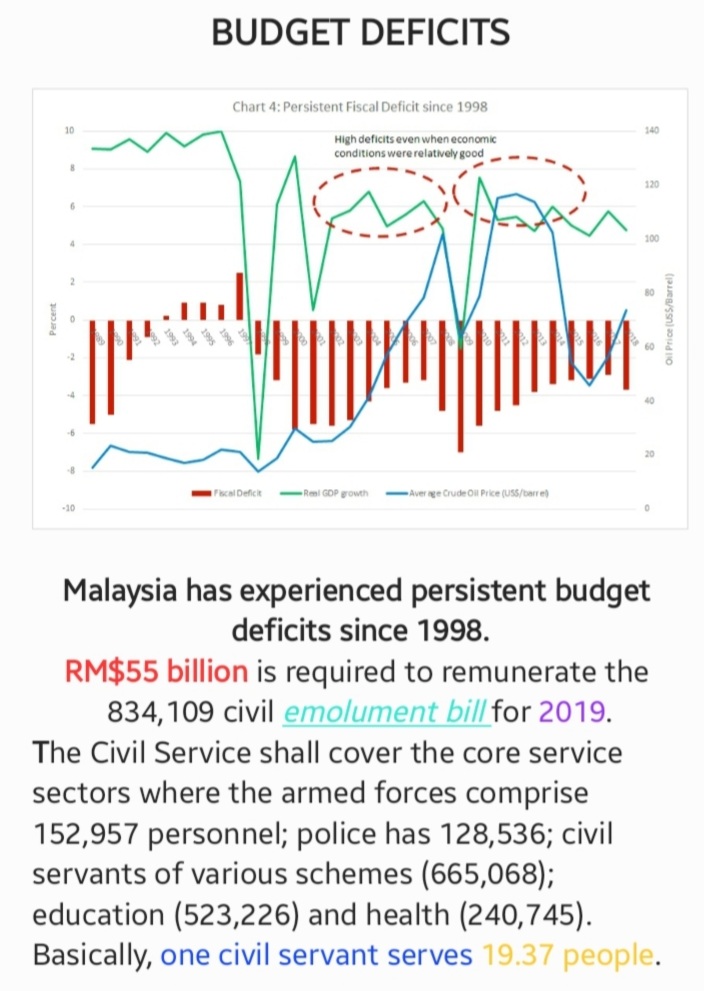

1] THE BUDGET 2023 will allocate RM388.1 billion for spending, of which RM289.1 billion is for operation expenditure and RM99 billion for development expenditure – once again amplifing the dire direction state of nation is heading. Only 25% in budgetary allocation is devoted to sustain developmental endeavours, whereas three-quarters of expenditure are to service day-to-day operations or for every ringgit, 75 sens go to maintain and retain the civil service sector and its pensionable remunerations.

[In the 1960-70s, nearly half of a National Budget is devoted to development purposes towards long-term returns on investment, covering widely upon education, socio-economic services and the health segments]

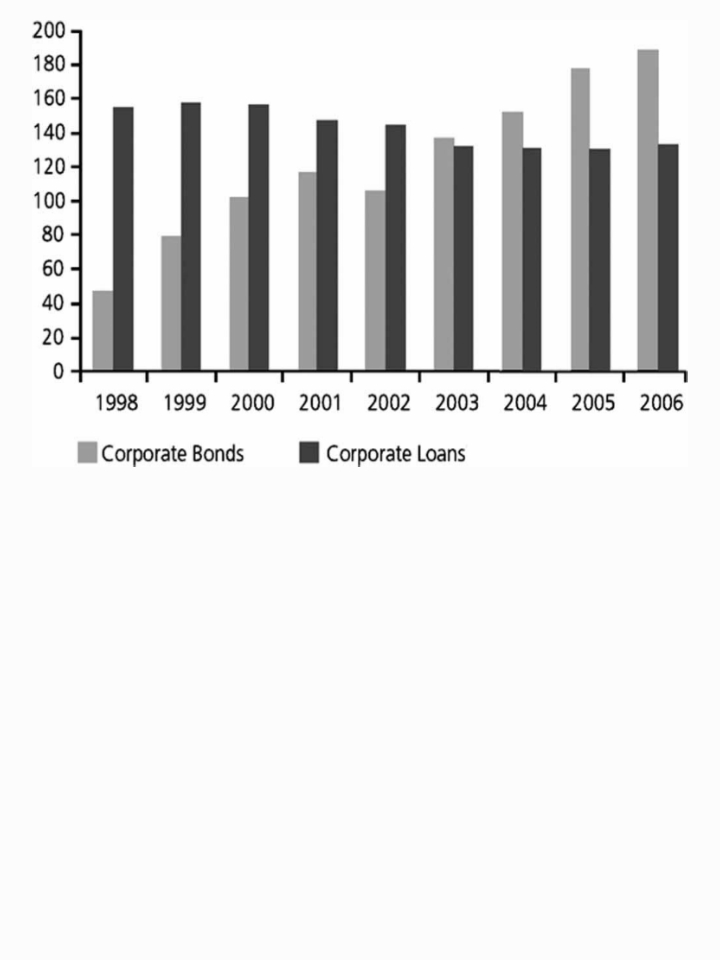

Whereas, nowadays, the national debts are increasing as a resultant outcome of continous high operation expenditure with consistent budget deficits since 1998:

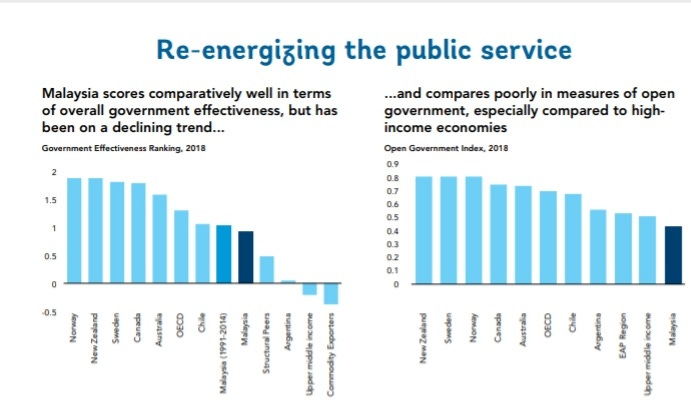

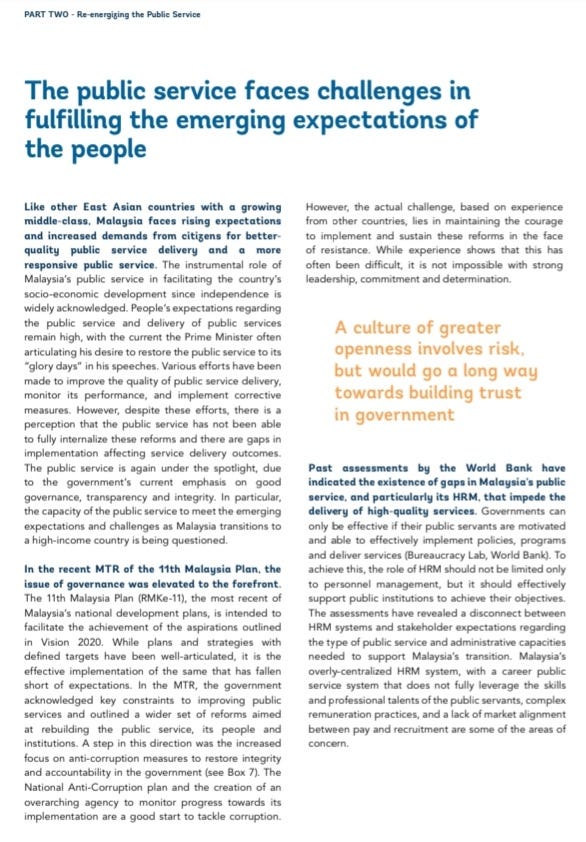

The public sector, through the decades supporting the dastard nature of kleptocractic practices, has not met the performance criteria deemed a necessity to spur economic development, but furnished as an intermediary medium between political master and to rentier capitalism in vested projects’ implementation. Some elements have even aligned with the political kleptocrats and clientele capitalists in helping themselves in gorging unfetted gains.

Not infrequent harsh critique of an ethno-administrative regime is the poor performance of the civil service, its sluggish deliverance of public goods and services, slackness in work productivity, and widening misuse of public funds – as observed by the World Bank consultation teams: Over the years, various efforts have been undertaken to improve public sector productivity in Malaysia, but not unsurprisingly, with limited resultant outcomes. Core difficulties often lie in translating researches on public sector productivity findings into policy actions. The elements constraining effort on improving public sector performance centre on administrative human-resource incapacity, a broadbase corruptive regime with burden of privileges mentality, a lost community soul living in a society laced with serial systemic odious practices, including money-laundering, (read icij, Panama Papers).

Over the years, various efforts have been undertaken to improve public sector productivity in Malaysia, but not unsurprisingly, with limited resultant outcomes. Core difficulties often lie in translating researches on public sector productivity findings into policy actions. The elements constraining effort on improving public sector performance centre on administrative human-resource incapacity, a broadbase corruptive regime with burden of privileges mentality, a lost community soul living in a society laced with serial systemic odious practices, including money-laundering, (read icij, Panama Papers).

The Pandora Papers exposè only widen the mired state of nation politico-economic praxis wherein RM$1.8 Trillion is siphoned abroad by corrupted compradore capitalists and their clientel ethnocapital; this amount is even more than the national debt of RM$1.5 Trillion in 2022!

Singapore has one time or another has a SG$1.57 Trillion in sovereign reserve while

Norwegian Sovereign Wealth, accumulated since exploitation of North Sea oil – about the same time that Malaysia started exploration of oil and gas off South China Sea – is a stacked US$1.2 Trillion.

Thus, the country has an outsized public sector which is imperfect in its non-productiveness (reference: World Bank (2019), Malaysia Economic Monitor: Re-energizing the Public Service).

All the above issues are aided and abetted by neoliberalism capital endowment in the guise of foreign advisors to dash any hope of an indigenous contribution to proper economic development but an economic growth praxis that engulfed a state of nation crises after crises with subservient subsidies mentality and those consistent provision supports that inhibit an alternative mode in uplifting the development of a country.

2. THE REVENUE for 2023 is projected to be RM$291.5 billion compared to RM$294.4 billion last year; the nearly +RM$90 billion shortfall is to be covered by debts financing and dividends from Petronas and Khazanah, plus tax base which is already too pit-bottom shallow. (The T20 segment makes up 80% of Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) contributions; out of 16-million workers, only 2.5 millions are tax-payers).

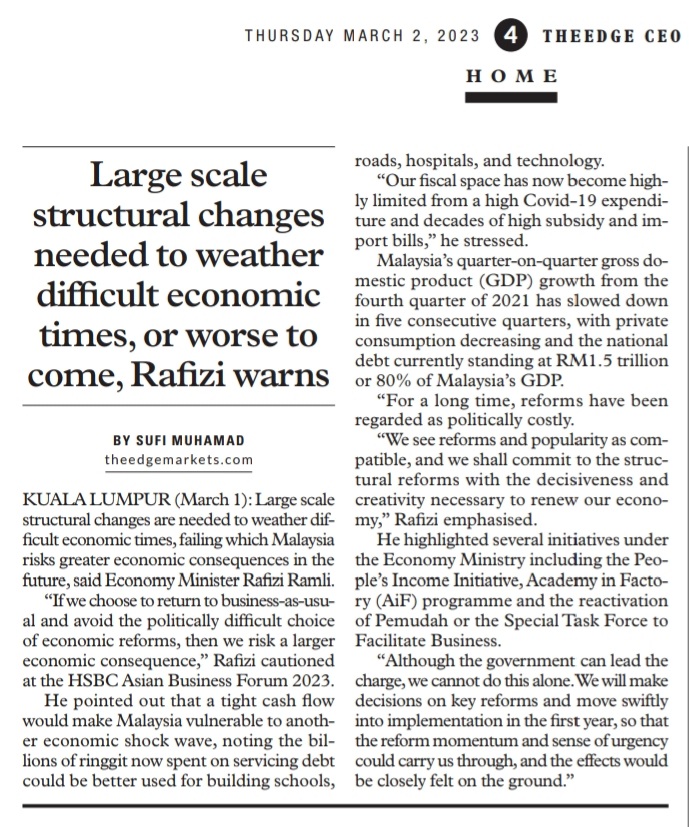

The deferment in implementation of the capital gain tax and a wealth tax until 2025 only indicate the preference to capital interests than immediate rakyat-rakyat beneficial wellbeing. There is a definite need for reforms towards long-term fiscal sustainability if governance is committed to improving the credibility of the fiscal policy conduct and framework through more holistic reforms which should include revenue enhancement measures and subsidy rationalisation programmes while maintaining macroeconomic stability and safeguarding the wellbeing of the rakyat.

Unfortunately, the social assistance allocation of RM$8 billion to cover the needs of 8.7 million people will amount to a paltry RM$920 per person per annum, (theedgemarkets, 27/02/2023).

Listen to Treasury Secretary General Datuk Johan Mahmood Merican on the thought process that went into drawing up the budget HERE.

3. THE ECOFOOD SECURITY issue is inadequate in tackling daily bread-and-butter problems by not prioritising the maintenance of open and operational food supply chains. Equally in importance is to address other looming threats to food security including climate change that is already damaging food production as temperatures and precipitation patterns fluctuate. Further, the wide-spread urbanisation has caused a proportionate decline in the agricultural labour force as the current cohort of farmers age and fewer young people are interested in taking their place.

Therefore, the country’s land-use practices in catering large-scale agribusiness and real-estate development are unsustainable, especially with introduction of considerable imminent deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and chemical pollution.

Given these challenges, agricultural research and development (R&D) must be a core component of any national food security policy. Climate-focussed research is also needed to develop the various crop varieties that are tolerant against a more uncertain climate and extreme weather events. More appropriately – in any quadrilateral helix operational approach mode (with distinctive articulated strategic goals) – there is a need for a strategic reorientation in the ability to resolve present and future food scarcity by collaborating with international bodies and countries to mitigate the ecofood insecurity issue, (BowerGroupAsia, 2023).

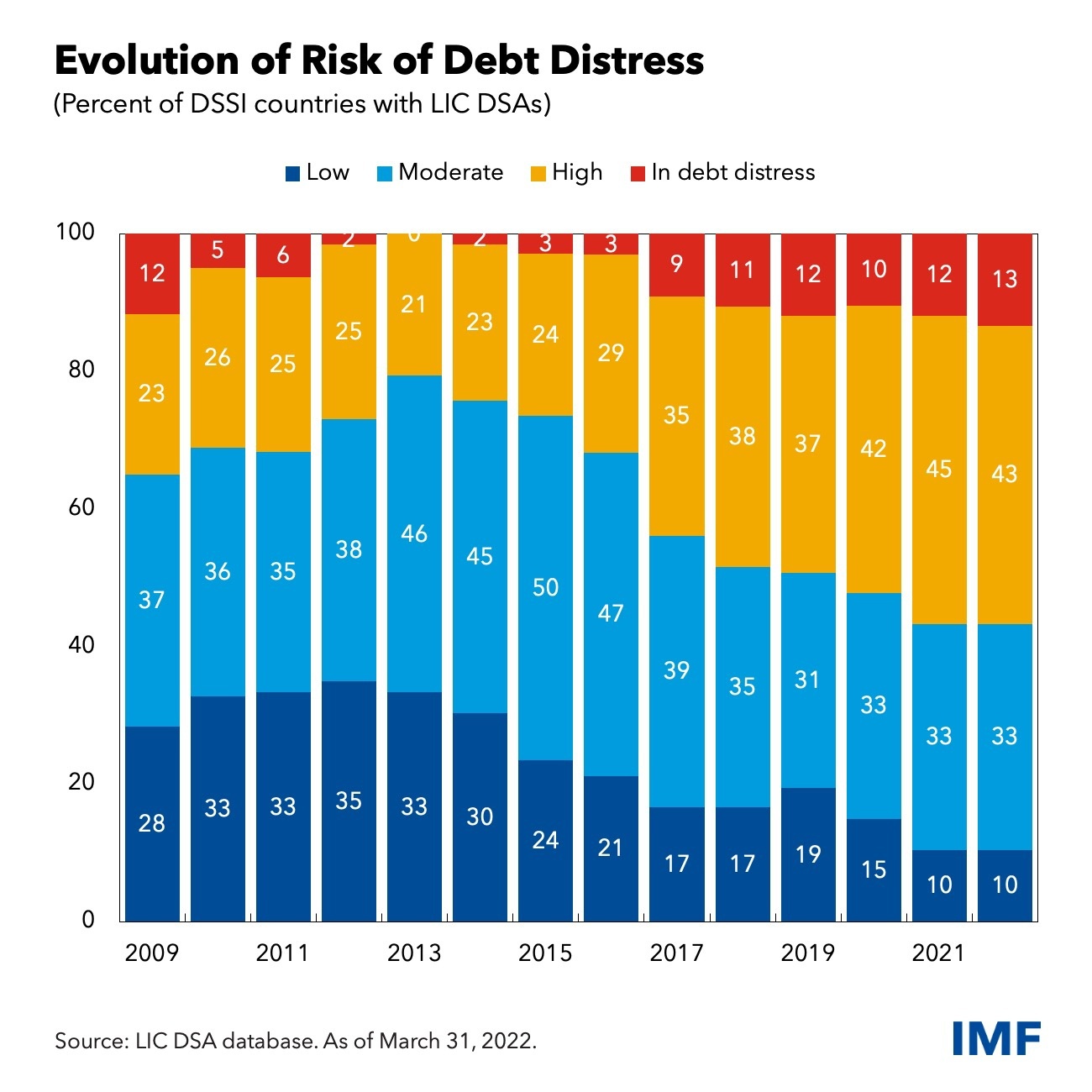

4] THE NATIONAL DEBTS shall slow the economy growth path for many years to come; it could likely be seized upon by the oppositions ahead of state polls and could dilute the credibility of the Anwar governance, so said BowerGroupAsia senior analyst Arinah Najwa.

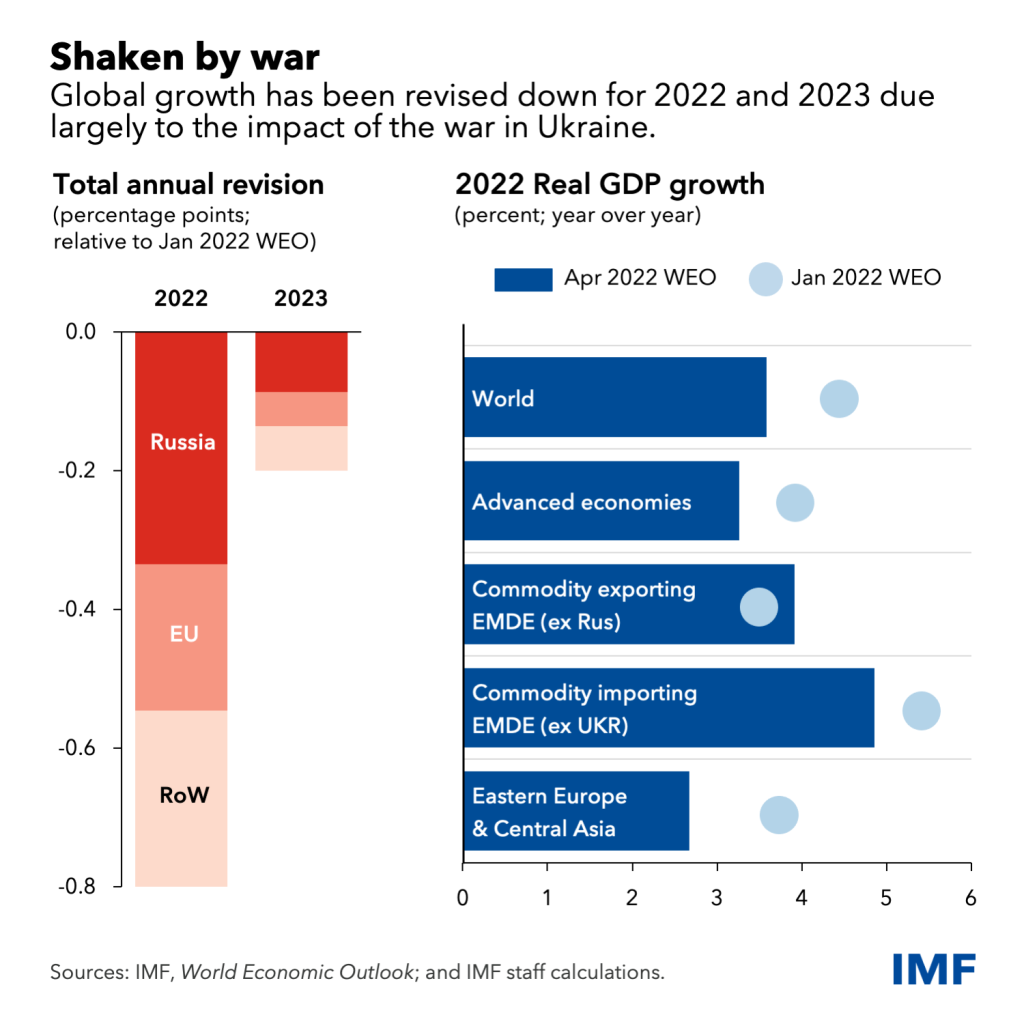

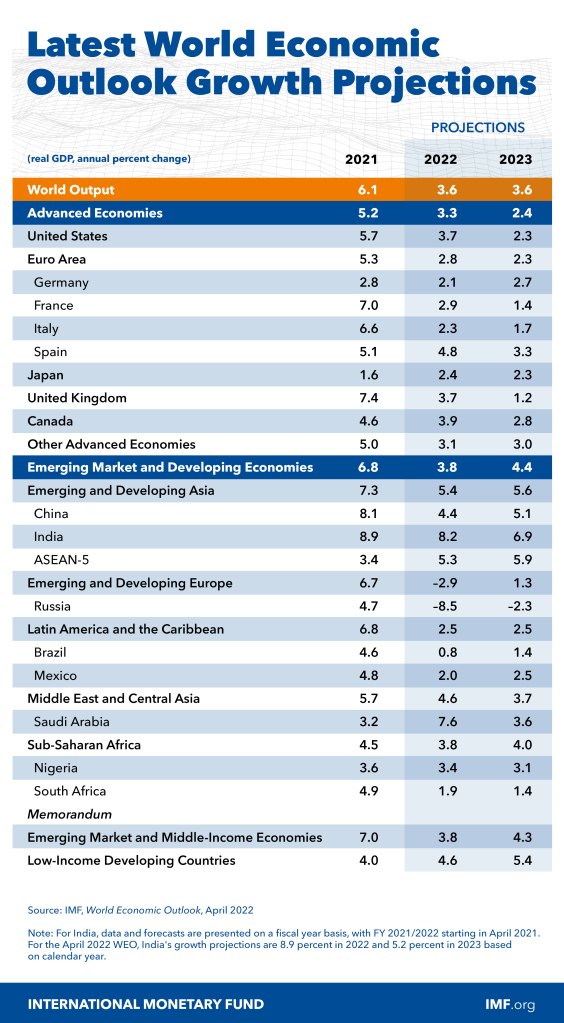

Further, economists do not expect the nation’s strong economic growth witnessed in 2022 to continue into 2023 as consumer pessimism weighs significantly on growth which is affected by Global North consumption patterns and the cosmopolitan centres’ inflationary trends. Indeed, many economists believe that domestic consumption will slow significantly by end-2023 due to cumulative inflationary pressure, the waning effect of the Employees Provident Fund’s special withdrawal scheme that was imposed in April 2022, and the expiry of the car sales tax exemption. This could be further impacted by the government’s potentially more restrictive spending as operational expenditures enlarged, (see the report in FitchSolution in Appendix).

5] THE MEDIUM-TERM FISCAL FRAMEWORK

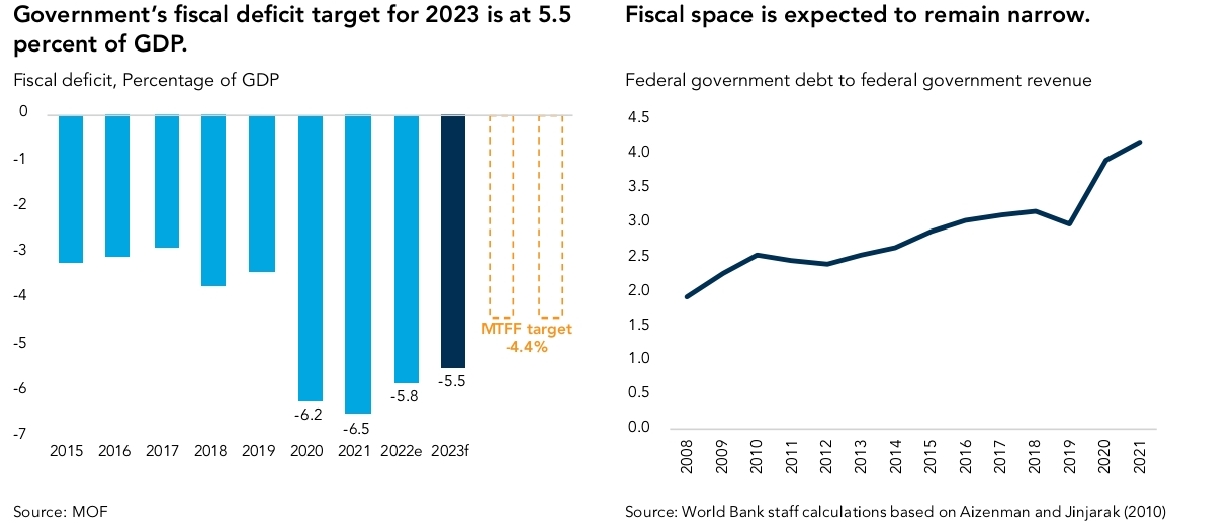

For 2023, UOB Kay Hian Research foresees gross domestic product growth halving to about 4 per cent due to a slowdown in domestic consumption in the country in alignment with IMF’s projection. Under the Medium-Term Fiscal Framework (MTFF) 2023-2025, total revenue in the medium-term is projected at RM854.3bil or 14.7% of gross domestic product (GDP), mainly contributed to non-petroleum revenue which is estimated at RM699.5bil or 12% of GDP.

The fiscal policy in 2023 will definitely need to maintain agility, supporting the growth momentum towards achieving the national development agenda. The fiscal resources have to be channelled through a more targeted approach and allocated in priority areas, particularly to enhance economic capacity and country’s competitiveness.

While the government’s budget remains expansionary to provide sufficient fiscal support in ensuring the rakyat’s well-being, the continue undertaking of premier economic reforms has to be sustained to maintain the fiscal consolidation plan. This is more vital since the Federal Government’s revenue collection in 2023 is projected to be lower at RM272.6bil or 15% of GDP due to anticipated lower non-tax revenue collection. The non-tax revenue is expected at RM$67billion, declining 23% from 2022 due to lower dividends from government entities.

A positive way is to emphasis more on the quality and multiplier effects in creating high quality jobs and building key ecosystems to help the development of local capitals and specifically SME entrepreneurship players.

The SMEs are the backbone of Malaysian economy:

The small and medium enterprises (SMEs) make up 99% of the 920,624 business establishments in Malaysia. In 2018, SMEs employed 66.2% of the workforce in Malaysia, contributing RM$522.1 billion, or 38.3%, to the Malaysian GDP. They are classified into three categories: micro, small, and medium, defined by industry, sales turnover, and the number of employees. Micro-enterprises make up 76.5% of Malaysian SMEs. In contrast, medium-sized enterprises comprise only 2.3% of SMEs.

Despite being the backbone of Malaysia’s business environment, “SMEs perform relatively poorly in digitalization. There exists a digital divide among businesses in Malaysia”, write Amos Tong, an economics undergraduate at UCLA, and Rachel Gong, a researcher at the Khazanah Research Institute in Kuala Lumpur. This owes to the fact that the larger pool of micro-SMEs entrepreneurs are marginally unskilled and too underfunded in their enterprises’ administration and daily operations; compounded that there are much to do Catching Up:

Inclusive Recovery and Growth for Lagging States in Sabah and peninsula Malaysia which needs wider spread-effect from economic development, (World Bank, 2022).

Related to the bigger picture is the question as to in what ways can the SMEs contribute to the industrial development programme in the country.

How would the New Industrial Master Plan 2030 in the third quarter of 2023 shall emerge has a bearing on cementing the future industrial platform of a nation and what intermediary roles would the SMEs play in the commodity supply (and value) chains?

Shall we revisit the E&E sector to tap upon the peripheral benefits in the West vs China-Korea-Japan Chip War? or we might got submerged within the geopolitical trade-technology warfare?

Can we generate the next generation of New Gen armed with TVET, but without adequate polytechnic knowledge nor polycrisis management skills to confront future geoeconomic scenarios?

Owing to the diverse array of activities in SME and different genres of entrepreneurship, whatever assistance offered may not be enough to aid this vital segment of the national economy. LISTEN to Chin Chee Seong, National Secretary General of the SME Association of Malaysia on his takes.

Shall we go boldly forth to seek new frontiers where everyone has been before but got net-meshed in a monopoly-capitalised infrastructural platform foundation?

In the Malaysia Economic Monitor, February 2023, the World Bank is rather persistence in advocating the advancement towards a digital economy. Though while advocating Big IT development as a means of continuing capital deployment – and capital accumulation with extracted value from states – to ensure Global North infrastructural platforms Big Tech benefiting on expansive exploitation, through global labour arbitrage where underemployed labour is truly exploitated, (read STORM, 2022, Big Tech Large Gig), and STORM 2023, Big Tech in Marine Cabotage where the infrastructural platforms could hold our nation to technical ransom on undersea communication cabling installation and maintenance.

Indeed, the large RM$1.5 billion IT allocation will benefit only wealthy and the well-connected companies – not our local SMEs entrepreneurs – with their huge expenditure for consultancy pservices.

It also highlights the longer term on how to rebalancing towards deregulated finance and foundational service sectors (like infrastructural platforms which are incrementally becoming invasive as techno-feudalism in country) franchised by privatisation and outsourcing to Global North monopoly-capital whereby compradore capital accumulates their capital as functioning intermediaries.

Related readings herein: Financialisation Capitalism Digital Feudal Lords

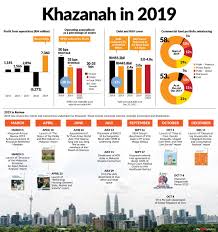

8. THE PETRONAS AND KHAZANAH FACTORS

A good prospect is to spur local start-ups, government-linked companies including Khazanah Nasional Bhd and EPF in investing RM$1.5 billion for those that are innovative and have high-growth potential. This model will see a lead company (not as yet identifiable, but capital shall continue to dominate as Jomo observed in a French Embassy-sponsored forum) that shall partially or fully take over the operation of TVET institutions and revamp training programmes so that they meet industry needs: provisio it is free from identity politics but based on Madani politico-economics mantras.

Inheriting such a burgeoning debt burden, sovereign wealth fund Khazanah Nasional Bhd could sell its assets to raise cash for the state of a nation as she is sitting on assets easily worth more than US$30.5 billion (December 2021) that could probably raise over 10% of the government’s +RM$1.5 trillion debt and contingent liabilities.

Another financial resource bulwark is with Petronas as it is financially in a comfortable position to pay, given that its total assets has strengthened to RM$699.5 billion in the first half of 2022.

Alternatively, government-linked companies (GLCs) and government-linked investment corporations (GLICs) would also likely be encouraged to pay higher dividends. The government could tap these state enterprises to help out just as like the recent RM$58 billion stimulus package to counter impact of the Covid-19 pandemic 2020 crisis. The GLCs and the crown-jewel GLICs have to be reformed to endow the national coffers.

An excellent yet viable alternative foundation is the formation of a new sovereign fund to be created with Khazanah and Petronas seedings.

The debt financing of a national economic development shall demands certain structural changes, (see Appendix B). The mere fact that much resistance to change by clientel-capitals to inhibit every rakyat-rakyat to have a share of the common wealth only befalls the stake – and sake – of a nation.

9] THE DEBT FINANCING DIMENSION

With government revenue projected to remain low and structural expenditures still increasing high, this has led to further narrowing of Malaysia’s fiscal space (see right chart below):

Using the ratio of the Federal Government Debt to the revenue collection as a reference point, the World Bank has indicated that Malaysia’s fiscal space has gradually narrowed since 2012 and became tighter post-pandemic.

The government also expects revenue to decline over this period, from 15 percent of GDP in 2023 to an average of 14.7 percent in 2023-2025. Overall, the fiscal deficit is expected to consolidate at a gradual pace with the overall balance averaging at 4.4 percent of GDP for the MTFF period.

The current fiscal consolidation strategy – via spending reduction – is, to many national economists and political analysts, (bfm.my, IDEAS, O2 Survey, theedgemarkets), rather challenging, given the current tight spending domain. Firstly, the combined spending on structural expenditures is already at high levels; and secondly, other Operating Expenditures components such as supplies and services, and grants and transfers have been on a declining trend or are already at low levels.

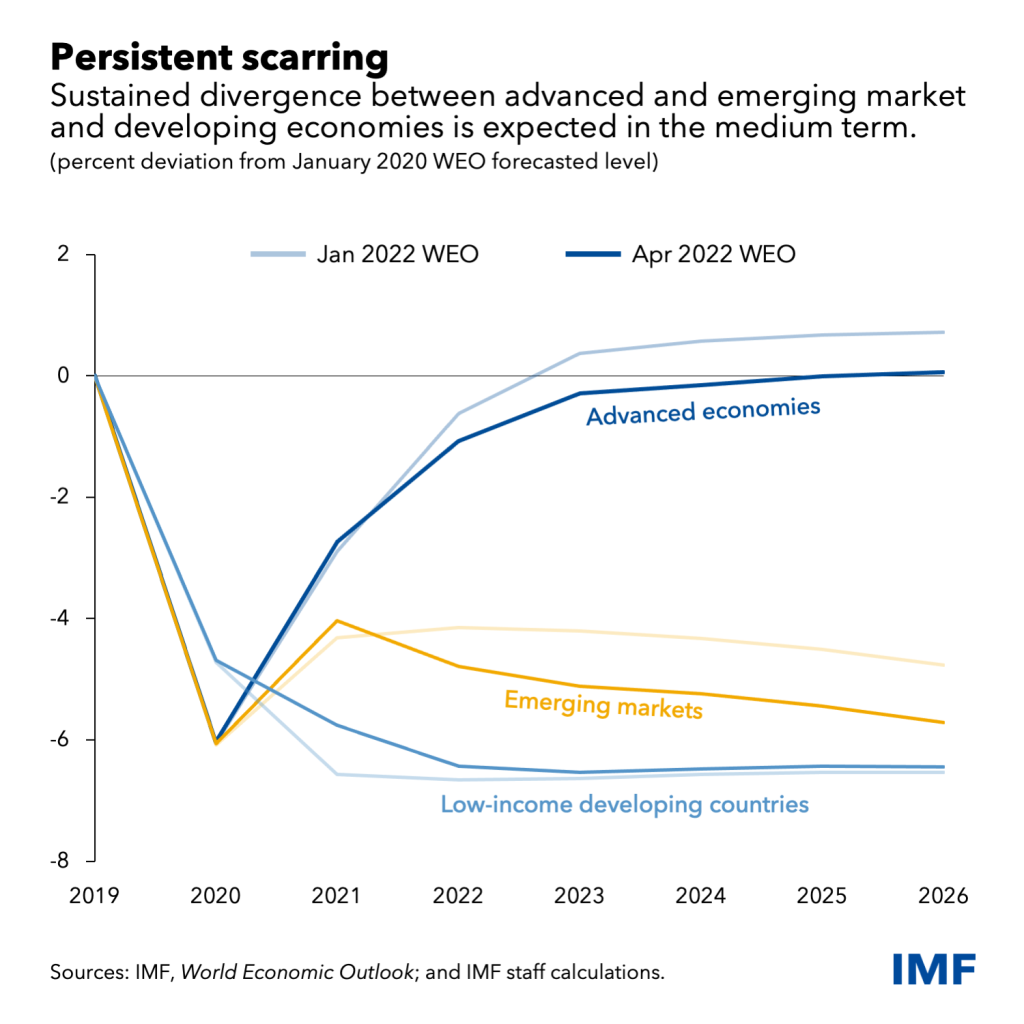

Thirdly, the Unity Governance has inherited a legacy of lackadaisical administrative performances by preceding regimes who had mangled, looted, overturned legitimate-elected government, siphoned off national coffers at a time when the nation is in deep sovereign debts, weakened by commodity supply chains in a semi-deglobalised environment and with the world economy growth marginal though inflationary trend is cooling:

10] CONCLUSION

The Budget does not provide details as to how subsidy rationalisation will unfold, other than the already increased electricity tariff for large corporations. The reduction in subsidy expenditure seems to be primarily attributable to the lower oil prices (as compared to 2022). As a nation, we are on a neo-colonial dependency development mode, and always, on subsidy dependence to crawl ahead.

With neoliberalism economic policies as the preferred approach since independence , we are but without shared common prosperity nor progressive elements of developmental governance ethos or a new ideal socialist praxis referencing an equitable distribution of social wealth. The preferred economic growth model is still undermining, and underdeveloping, the country’s economic developmental full potentialities.

In short, if development in Malaysia is to be self-directed and comprehensively inclusiveness, then traits of such a “developed society should also embrace secularisation, commercialisation, increased social mobility, increased material standard of living and increased education and literacy besides such things as the high consumption of inanimate energy, the smaller agricultural population compared to the industrial, and the widespread social network” (Syed Hussein Alatas, in a paper presented at the Symposium on the Developmental Aims 1996, pp 70-71).

There is not much leeway to manoeuvre in an inflationary-inflicted terrain, and a heavily indebted and morbid economy, but the nation has to be reformed boldly to sustain a growing developmental path that is wealth-sharing with opportunities for all.

APPENDIX A

FitchSolution Assessment

APPENDIX B

Structural Changes

APPENDIX C

Inequality and Class

The persistent question on Race and Class, Poverty and Inequality dimensions are succinctly explored HERE, with referenced links and video contents.

An extracted excerpt is expressed herein :

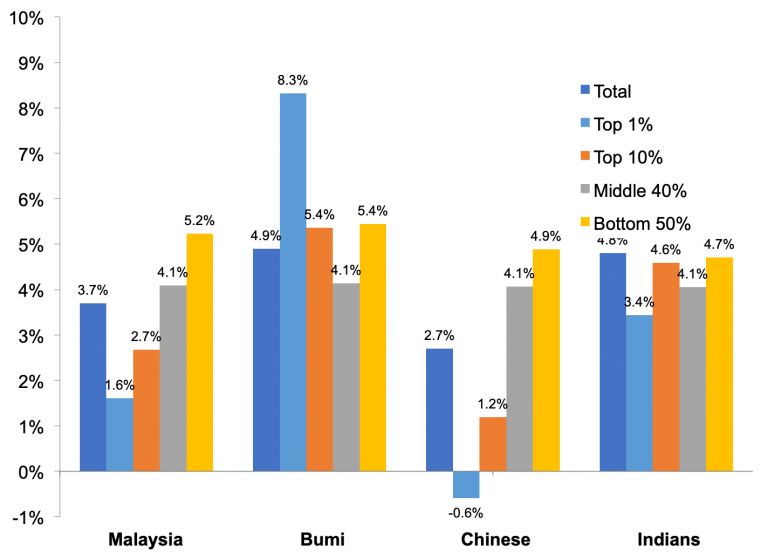

Post May 13, 1969, the country’s growth policies have shifted from strategies with an emphasis purely on economic growth toward a strategem focusing at combining growth with income inequality reduction between ethnic groups. This policy shift was formalized in the New Economic Policies (NEP) for the period 1971–1990 (see Economic Planning Unit, various years).

The relationship between economic growth and ethnic diversity (Agostini et al., 2010, Gören, 2014,

Iniguez-Montiel, 2014) is supported by a body of economic literature that finds that ethnic heterogeneity induces social conflicts and violence, which in turn, affects economic growth (see Easterly and Levine, 1997, Mauro, 1995, Montalvo and Reynal-Querol, 2005).

The negative consequences of ethnic diversity imply that adequate policies are required to ensure that the benefits of any economic growth are equally shared among all ethnic groups.

Unfortunately, six and a half decades plus downstream, the politico-economic mission objectives have yet to attain that vision reality. The 2022 budgetary version is just as bad as previous years’ The Budget and the Buffons: misallocating rare resources as well as accentuating the dominance of ethnocapital over rakyat-rakyat labour. The continuance of an neoliberalism economic approach post-independence only restrains the forward thrust in engendering a truly enduring national developmental effort.

RELATED READINGS

Renewal of the Socialist Ideal

You must be logged in to post a comment.