31st May 2023

1] INTRODUCTION

The IMF Report on Malaysia 2023 projects a slower economic growth this year owing to a high global inflation rate and the cross-border conflict between Russia and Ukraine. This institution expects the global economic growth to drop to 2.8 per cent this year, down from its earlier forecast of 2.9 per cent and in comparison to the growth in 2022 of 3.4 per cent. Consequently, a correlated decreasing growth in the country is expected.

2] ECONOMIC GROWTH DIMENSION

The central theme in a capital-driven economy is a system driven by endless economic growth impulse. This mode becomes the root of our multiple, interlinked, and the contributory and accelerating crises become embedded within the socioeconomic system. The consequence of this growth – especially with the Global North excessive material throughput – drives the ceaseless accumulation of capital where it builts upon a constellation of exploitation of labour and extraction of natural resources.

Capitalism – which surges from crisis to crisis – is leading us to ecological collapse, while creating inequality on its capital accumulation process through commodifying essential goods and services. It assumes the replication of neocolonial relations with the Global South, and committed neoimperialism in this endeavour.

One distinguished aspect clearly distinctive is that with globalisation, rentier capitalism compradores begin attaching to neo-imperial monopoly capitalism and their linkages to the global commodity chain dimension because of the multiple roles of rent intermediaries between capital and its accumulation. The consequence is that these capitalists are accentuating wealth disparity with the working class.

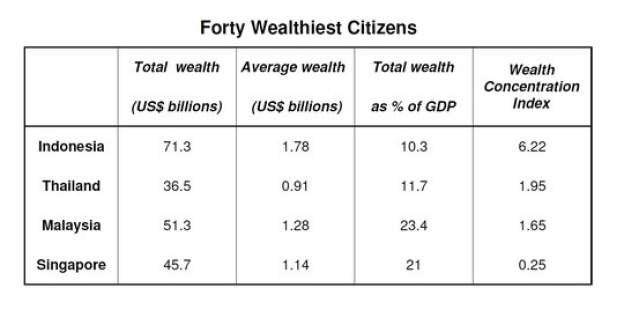

Malaysia’s 50 Richest 2020: bottom 40% of population only get 16.4% of the national income share of wealth; see Khalid 2019.

The absolute gap across income groups has increased with the top 20% of population – the T20 – possess 46.2% of the national income share, while M40 have 37.4% but the bottom 40% of population – the B40 – only 16% share of national income.

Compounded with

i) Compared to many other countries that have graduated from middle-income status, Malaysia has a lower share of employment at high skill levels and higher levels of inequality.

The foreign cheap labour is the biggest policy issue in Malaysia because if they are cheap, our young people cannot get their wages up.

ii) There is a growing sense that despite economic growth, the aspirations of Malaysia’s middle-class are not being met and that the economy did not produced enough well-paying and sufficient high-quality jobs. There is a widespread sense that the proceeds of growth have not been equitably shared and that increases in the cost-of-living are outstripping incomes, especially in urban areas, where three-fourths of Malaysians reside. The UNICEF 2020 Report has shown that low income female-headed households are exceptionally vulnerable.

iii) The country shall, increasingly, need to depend upon more knowledge-intensive and productivity-driven growth, closer to the technological frontier and with a greater emphasis on achieving inclusive and sustainable development, yet this generation is not forthcoming.

iv) According to the World Bank’s Human Capital Index, Malaysia ranks 55th out of 157 countries. To fully realize its human potential and fulfil the country’s aspiration of achieving the high-income and developed country status, Malaysia will need to advance further in education, health and nutrition, and social protection outcomes.

v) Key priority areas include enhancing the quality of schooling to improve learning outcomes, rethinking nutritional interventions to reduce childhood stunting, and providing adequate social welfare protection for household investments in human capital formation.

Companies need to organise their training and reskilling programme as part of their business strategy. This is

also truism for the civil service, (see STORM 2023, Place, Position, Power of Public Sector) because the economic dimensions are changing very rapidly.

On one prominent aspect is that lower economic growth translates into lower ROE for FDI which is the Malaysia’s structural weakness of

relying on debt-driven domestic consumption to fuel economic growth.

Basically, Malaysia’s growth strategy of the last 25 years since the Asian Financial Crisis was a debt-driven domestic consumption story. This is the dominant structural issue that Malaysia now faces conspicuously, and has not only to destruct its legacy and lack lustre entities but to construct a new economic development mode, (see STORM April 2023, Structuring lnstitutional Reforms for Economic Development {SIRED} ; TAPAO; and Madani Malaysia praxis).

It had once expressed if development in Malaysia is to be self-directed and comprehensively inclusiveness, then traits of such a “developed society should also embrace secularisation, industrialisation, commercialisation, increased social mobility, increased material standard of living and increased education and literacy besides such things as the high consumption of inanimate energy, the smaller agricultural population compared to the industrial, and the widespread social network” (Syed Hussein Alatas, “Erring Modernization: The Dilemma of Developing Societies”, paper presented at the Symposium on the Developmental Aims 1996, pp 70-71).

Therefore, the key challenge for the next two decades, at least, would be to improve the indigenous innovative capacity of domestic firms and to continue to raise the productivity of Malaysian workers and firms whereas succeeding ruling regimes had given preference towards corporate capital than socioeconomic determinants of rakyat2 labour well-being, (see STORM, May 2023, MADANI the SCRIPT : labour exploitation and capital accumulation factors).

3] CRITIQUE OF THE IMF REPORT

On the inflation spectre, though it is projected to remain elevated at about 3.25%, there is a likelihood of a persistence in core inflation. Then, there is also an emerging evidence of a build-up of demand-side pressures, adding to higher prices, (see various MIDF Research reports).

Further, with record spending on subsidies, though seen from within the country that the inflation had not surge in tandem with global food and commodity prices, but nevertheless, there was still on the upward trend for most of 2022, reaching 3.3% for the year that may migrate to the later part of year.

Therefore, monetary policy would require further tightening to keep inflation contained and rakyat² expectations well anchored.

Secondly, whether the gradual fiscal consolidation strategy, as set out in the 2023 Budget, can be set to rebuild buffers has yet to he discerned. The national debt is yet to be on a downward path but instead has been tracking upwards. The ability to reduce overall fiscal risks – high budgetary expenditure on top of repayments to 1MDB debt interests, and the efficiency to collect due corporate taxes – is still an unknown uncertainty. Debt repayment is the second highest operational expenditure in the 2023 Budget, where 18.5 percent is designated to repaying public debt.

This owes to the fact the previous governance had not performed due compliance, expecially durable revenue collection measures of high quality and enforced with prudence.

Preceeding regimes had constant, and continuous, budget deficits (meaning it spends more than it brings in through taxes and other revenue), and had inadvertently borrowed huge sums of money to pay its bills.

If these measures are not applied bluntly, then likely there is not much of created space for critical investment needs and, most importantly, for targeted transfers to low-income households. Further, if these revenue-collection tasks are well coordinated, and managed administratively well, this would help market confidence in the country’s strong fundamentals.

Thirdly, the unity government’s commitment to fiscal reforms is highly appreciated by capital and endorsed by labour. As such tabling of the Fiscal Responsibility Act is most welcomed. Further, the planned subsidy reform, and plans to develop a medium-term revenue strategy, would positively tighten the economy, and may bring the currently accommodative stance to neutral. What this means is that the approaches would well be kept inflation contained, and thereby, rakyat² expectations anchored.

MIDF Research has indicated that Malaysia’s growth of gross domestic (GDP) is set to increase 4.5 per cent for this year and 2024. In a sense, the structural reforms initiated by the unity government is on the correct Madani Malaysia pathway to an economic growth, (see SIRED, 19/04/2023).

However, though the economy is growing but with unbalanced development where geographically some states in semanjung and in the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak are still stumped by retarded development.

As an instance, ten years ago, the median household income in Kuala Lumpur was 2.6 times higher than in Kelantan; latest data indicates that this ratio has crept higher to 3 times higher.

As stated, of great concern are regional inequalities as in Sabah and Sarawak where the rights to access to basic infrastructure are sparse or not in existence.

In 2016, nearly one in three households living in Kelantan do not have access to piped water in the home, while one in nine households in both Kelantan and Sabah live in houses classified as ‘dilapidated’. In parts of Sabah and Sarawak where connectivity is poor, geographic disparities in access to basic services are more alarming: one in five households in East Malaysia live further than 9-km from the nearest public healthcare facility and secondary school.

Therefore, neoliberalism entity like the IMF’s Executive Board may praise country’s performance to elicit continuing consultation services and financial dispensing from western imperialism .

It is another budge in opening door to Global North domination and exploitation on national economic development – and indebting nations – than an equal exchanges for mutual shared prosperity among common wealth of nations.

This situation is the hallmark of neoliberal economic policies undertaken by country since gaining independence falling into the trap of development of underdevelopment,(read Ruy Mauro Marini, The Dialectics of Dependency).

4] IMF IMPERIAL INITIATIVE

IMF, and its sister entity the World Bank, is well-known for removing foreign exchange restrictions which retard the growth of global trade, with consequential international businesses being adversely affected.

Then, we have IMF’s High interest rates charged on its advances are considered one of the major disadvantages of IMF. So, the debt servicing for the less developed countries is difficult. For example, since 1982 the interest charged for loans out of the ordinary resources of the fund is 6.6 per cent. The interest rates payable on the loans made out of borrowed funds is as high as 14.56 per cent. So, developing countries experience a lot of difficulties in redeeming their loans borrowed from the IMF.

The IMF also often insisted upon that the borrowing countries have to reduce public expenditure in order to tide over their balance-of-payments (BOP) deficits. After 1970, the IMF imposed even stiffer conditional clauses. Among them are periodic assessment of the performance of the borrowing countries with adjustment programmes, increases in productivity, improvement in resource allocation, reduction in trade barrier, strengthening of the collaboration of the borrowing country with the World Bank, etc.

Then, further conditional clauses imposed by the IMF after 1995 are still stiff; just to state a few:

- liberalizing trade by removing exchange and import controls;

- eliminating all subsidies so that the exporters are not in an advantageous position in relation to other trading countries; and

- treating foreign lenders on an equal footing with domestic lenders. The fund maintains a close watch on the activities of the borrowing country related to monetary, fiscal, trade and tariff programmes. IMF’s intervention in the domestic economic matters of the borrowing countries places them in a difficult position.

As an example, of concern is that Malaysia was reported with US$57,566,000,000 of international debts in 2021, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators on International Debt Securities: translated as two hundred fifty-three billion two hundred ninety million four hundred thousand Malaysian Rinngit Debt or RM$7,449 per rakyat owing.

The domination by rich countries is the major weakness of IMF. Though the majority of the members of the IMF are from the less developed countries of Asia, Africa and South Africa, the IMF is dominated by the rich countries like USA and western European nations . It is said that the policies and operations of the IMF are in favour of rich countries so much so that the IMF shall be regarded as “rich countries’ club”. These rich countries are always partial towards the issues faced by poor countries.

As reported in The Hindu (May 2, 2007), Venezuela’s president Hugo Chavez announced his country’s decision to leave IMF and the World Bank. He accused them of exploiting small countries. He branded the IMF and the Wold Bank as “mechanisms of American imperialism“.

Moreover, the OPEC nation’s leader Mr. Chavez said: “we are going to withdraw…. and let them pay back what they took from us”. He then issued an order to his Finance Minister to begin proceedings to withdraw Venezuela from both IMF and World Bank.

5] CONCLUSION

IMF ‘double standard’ displays capitalism’s inherent inhumanity where human lives in the periphery are worth less than human lives in the metropolis.

The IMF’s behavior is thus reflective of the very nature of capitalism, of its essential inhumanity. It does not only mean “inhumanity” merely in the sense that it places profits before people, but also in the sense which follows from it, namely that it does not see all human life as of equal value – that it is surely, and necessarily, applies “double standards” in every sphere of life, (Prabhat Patnaik, 15/05/2023).

RELATED READINGS