collective on geoeconomics

1st May 2024

PREAMBLE

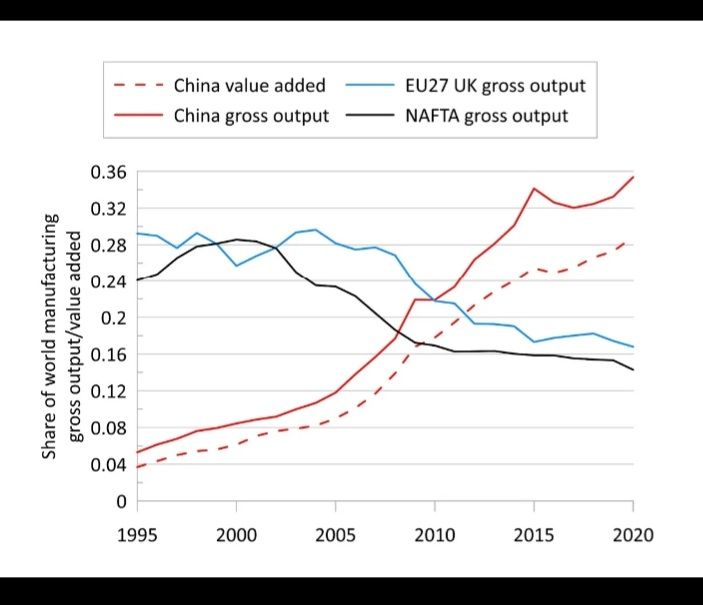

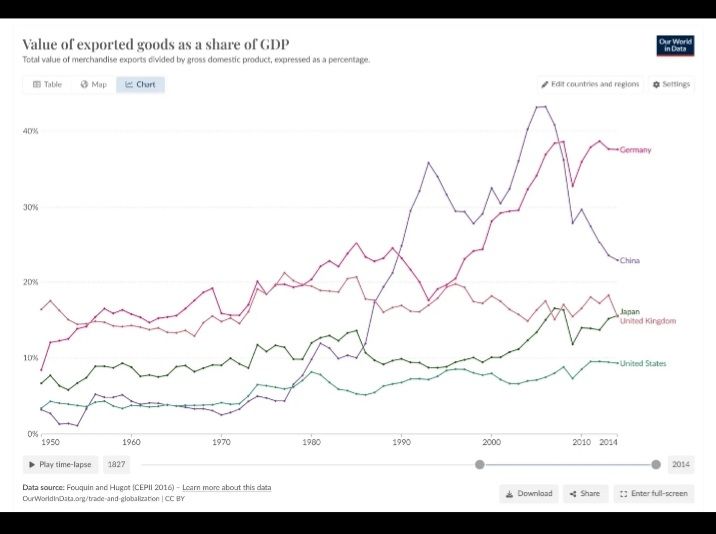

As a Hyper-Imperialism state cannot compete efficiently in economic performance with a civilisational state in Asia, therefore, it has to persuade China to commit an economic suicide, (John Ross, monthlyreview 20/04/24; John Ross, May 2023, peak China). However, such an U.S. geopolitical economics venture is only destabilising world economy through deglobalisation the supply chain. It is an undeniable fact during an era when China‘s manufacturing prowess is that of a socialism efficiency economic development model , she is able to promote an alternative economic model than American capitalism which is collapsing.

Since China’s economy was opened up during the 1970s at a time when Malaysia went through its industrialisation initiative welcoming the incursion of transnational companies onto an emerging economy, it shall be interesting to compare an indigenous socialist politico-economic endeavour to adapt to changing situational environment with one attached to the capital-led IMF/World Bank advisory-allegiance process that ensued an emerging economy’s slow-paced socio-economic developmental effort which has also deteriorated through the decades.

We shall use Kari McKern short piece as an exemplary exploration in comparative study.

Driving the dragon: China’s adaptive policymaking

By Kari McKern

![]()

China’s economic policymaking over the past few decades is a fascinating example of adaptive planning and strategic foresight. From pivoting away from reliance on globalisation to emphasising domestic infrastructure and poverty alleviation, tilting towards the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and now focusing on “high-quality development” (simultaneously upscaling advanced manufacturing while deflating the property bubble), China has demonstrated a sophisticated capacity to recalibrate its economic policies in response to the changing global and domestic landscape.

This remarkable stack of serial achievements, each built upon the success of the last and necessarily a prerequisite for the next, warrants close analysis of the methodology behind this success.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, China found its relatively low value-added, export-reliant economy vulnerable to the shock of lower demand. The crisis prompted a strategic shift towards bolstering domestic demand and reducing reliance on foreign markets. A significant element of this strategy involved huge investments in infrastructure required to build a nation-spanning high-speed rail network. With just over 300 kilometres completed by 2008, China extended the network to more than 43,000 kilometres in the following decade.

After independence gained, the Malaysian nation-state needs high-quality foreign investment to boost growth, but that requires broad reforms (already well expressed 20-odd years ago by Olin Liu et al in an International Monetary Fund Report, Malaysia: From Crisis to Recovery, IMF Occasional Paper No. 207) covering everything from the education system and labour participation to its investment promotional framework that were not completely executed by succeeding ruling regimes that cemented and colluded on clientele relationship upon a rentier capitalism platform peconomy.

Since 1997, the country had gone through four economic crises: the Asian Financial Crisis-1997, the dotcom-2002 crash and the Global Finance Crisis-2008, besides enveloped in the fourth crisis: Covid19-2020 of an Ecological-Epidemiological-Economical calamity, but each crisis had been concentrating on saving kleptocrates’ enterprise in support of capital than caring for a rakyat2 economic wellbeing, and as such, succeeding ruling regimes had not wholesomely restructure the political economy with a strategic competitive outlook, but maintained the feudal-clientiel capitalism superstructure.

“While other countries sprinted into high-income and developed nation status, Malaysia is jogging slowly,” said Raad, the World Bank country manager for Malaysia.

Whereas in China

But the strategy of improving transportation had larger goals in mind. It represented a new paradigm of mega-scale development and railway engineering driven by innovation in construction. The challenges overcome in connecting the diverse and often difficult terrains of the country honed the skills of Chinese construction firms in tunnelling and bridge-building. These capabilities signalled China’s transformation into a global leader in infrastructure development while stimulating domestic segments of the economy and reducing unemployment that was a direct aftermath of the global financial crunch.

By 2020, the Malaysian economy had contracted by 5.6%.

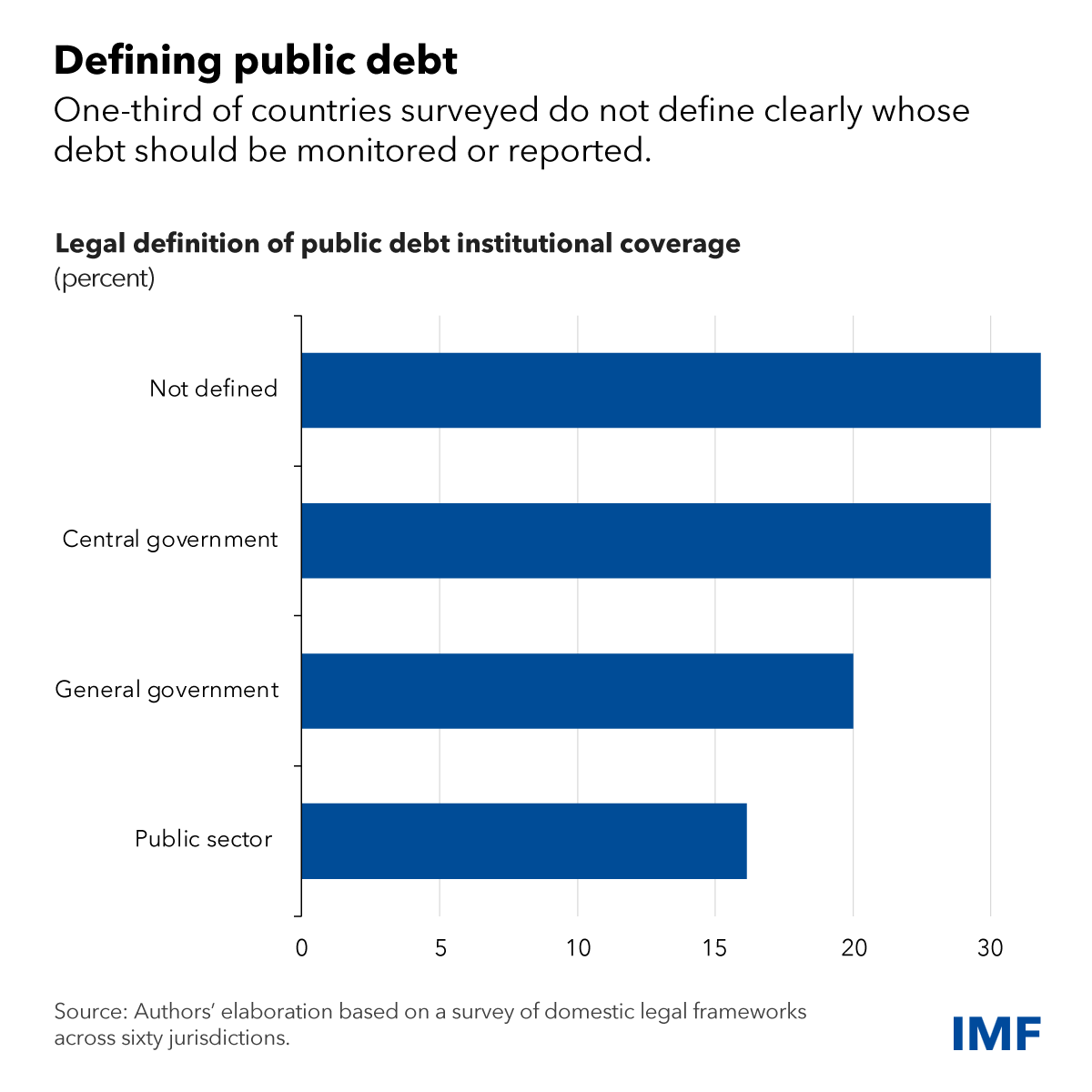

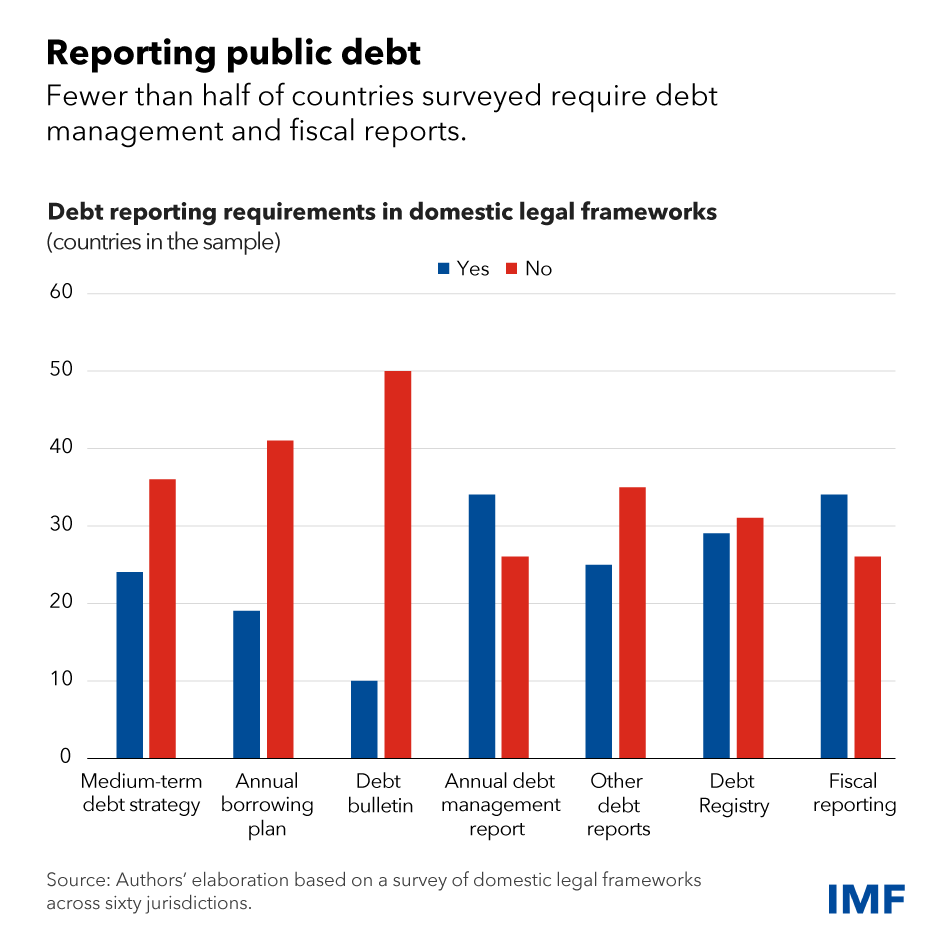

Not only has the national economy shrinks, its debt has surmountly increased concurrently :

Malaysia’s economy grew on average only 4% annually over the past decade, a marked deceleration from the 9% yearly growth from 1967 to 1997, according to a World Bank Report.

The stagnation has been analysed adequately by Sudhdave’s and in a firesstorms paper.

Whereas, in China

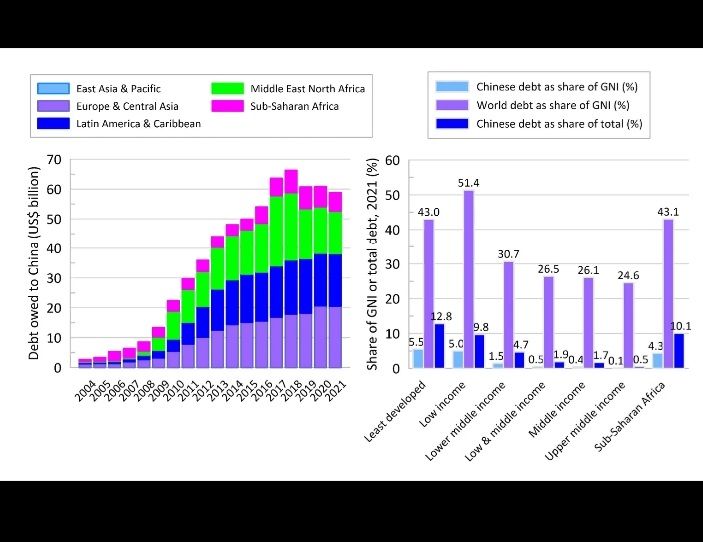

The domestic success of the high-speed rail projects demonstrated a capacity to complete large-scale infrastructure projects efficiently and effectively. The Belt and Road Initiative, announced in 2013, signalled China’s intentions to deploy its infrastructure prowess on a global scale, involving hundreds of projects across Asia, Europe, and Africa. The initiative encompassed not only transportation infrastructure like railways and ports but also energy projects and telecommunications networks.

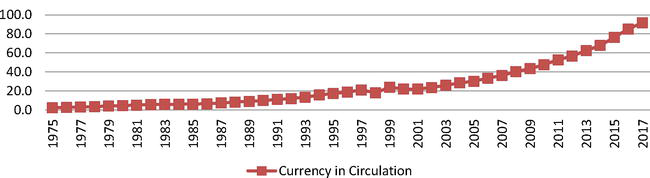

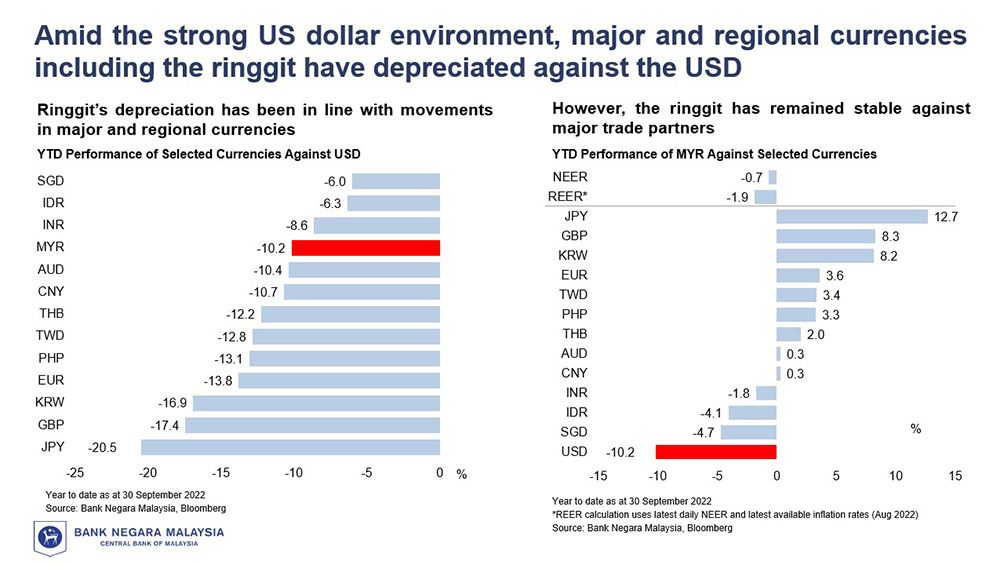

However, Malaysia economic stagnation in the country’s economic growth since the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC 1997) and the Global Financial Crisis (GFC 2008) persisted when the country decoupled from industrialisation towards a financial capitalism regime (see: Southampton’s Lena Rethel Financialisation and the Malaysian Political Economy; STORM, Financialization Capitalism in a Covid19 Political Economy, and firesstorms‘ Financialization of PNB Capital) where Khazanah and PNB playing primal roles, creating – instead of producing physical manufactured outputs – a high volume of monetary throughput with currency in circulation :

It is also the wide corruption embracement during the Najib governance where the 1MDB AFFAIR encouraged economic mismanagement and political uncertainty.

In China

By leveraging the experience and capabilities developed through its domestic infrastructure boom, Chinese firms embarked on BRI projects with a competitive edge in cost and expertise. This phase of Chinese economic strategy aimed at creating more expansive trade networks, essentially exporting the model of infrastructural development that had proved successful domestically. Furthermore, the BRI served to mitigate overcapacity issues within China by offloading excess production capabilities in steel, cement, and construction.

While the BRI continued to expand, domestic challenges such as the real estate bubble and concerns about environmental degradation prompted another strategic shift towards sustainable, high-quality development, which the Chinese government had anticipated in the “New Normal” strategy of the 2010s. China’s transition from a high-quantity to high-quality economic growth model began a decade ago. The shift was not a reactive measure but a policy-driven adjustment in response to changes in the global market. The Chinese government planned for a gradual deceleration of GDP growth from 10% to around 6%, aiming to maintain this rate before the unforeseen impact of the pandemic. This strategy marked a deliberate shift from high-speed growth to more sustainable, moderate growth rates, focusing on enhancing the quality rather than the quantity of economic expansion.

Meanwhile, in Malaysia

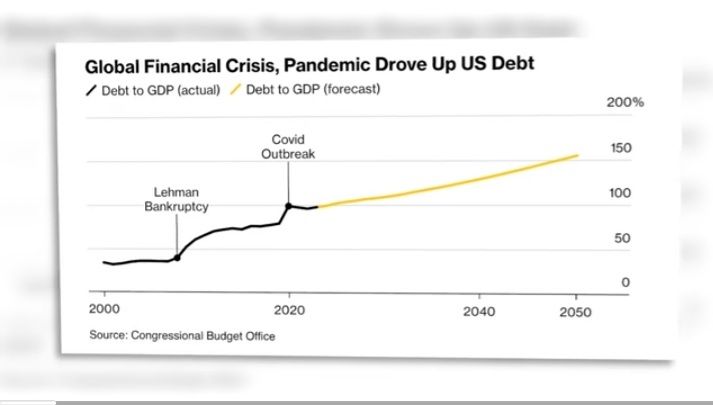

Succeeding ruling regimes are adamant on its ethnocratic economic thrust, clinging to political clientship under rentier capitalism whilst trying to “develop“ a national economy with an immense debt that is bloating yearly that by 2020:

We were there at 89.2%!

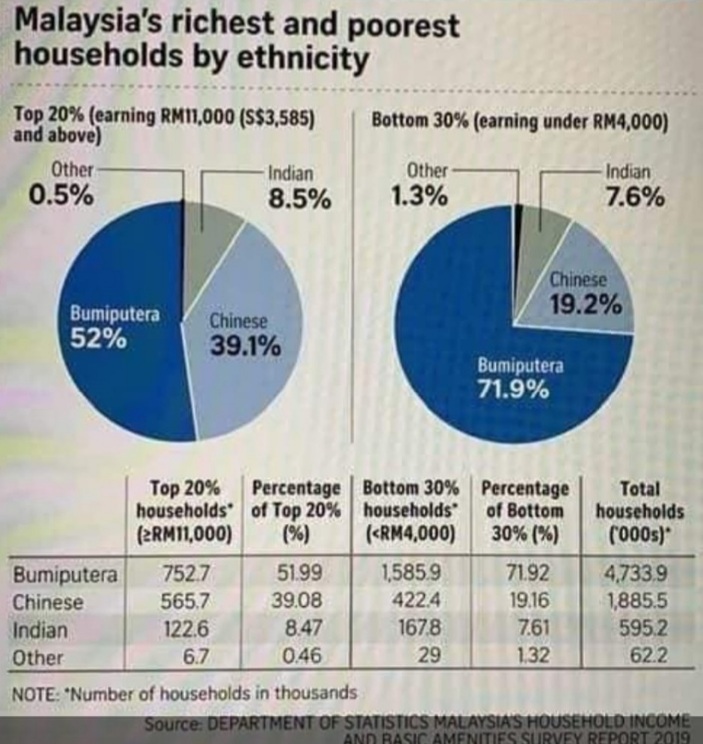

The primary losers under an ethnocratic-based economy means allocation of resources in any national budget is not according to means nor resting upon a national well-being agenda but racially, and non-secularly, biased, with resultant marked rise in absolute inequality through the years:

By 2020, Malaysia‘s average gross national income (GNI) per capita is estimated to reach US$11,200, still US$1,335 short of the current threshold level that defines a high-income economy. It is not surprising that Vision 2020 is not realized because, as Jomo expresses, the major political tendencies in Malaysia are invoking ethno-populist agendas that inevitably torn the already divided nation apart, even while vehemently claiming otherwise.

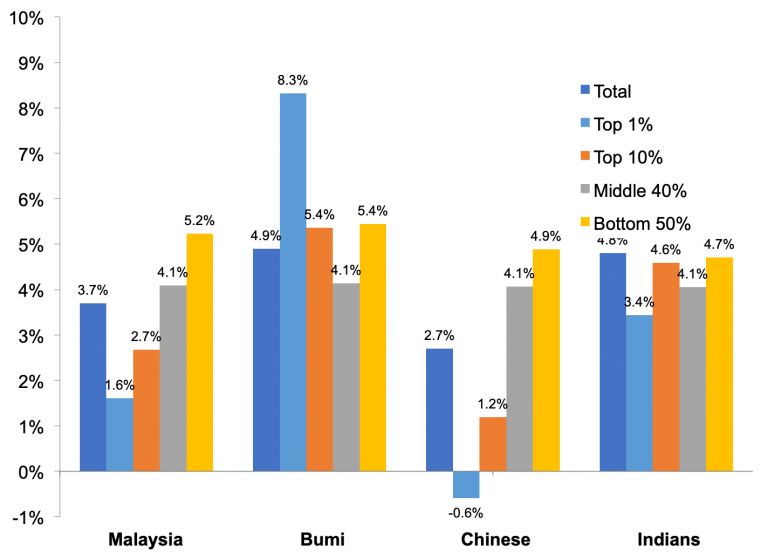

The direct beneficiaries are the Bumiputera who are the top income groups (the top 1 per cent and the 10 per cent) benefited the most from economic growth where in the top 10 per cent, the average growth rate per adult national income for Bumiputera is 5.4 per cent, compared to 1.2 per cent for Chinese and 4.6 per cent for Indians. While the gap in the growth rate among the different ethnic groups was large in the top 10 per cent; however, it is even larger for the top 1 per cent. In the top 1 per cent, the average growth rate for Bumiputera was 8.3 per cent, which is sharp contrast to -0.5 per cent for Chinese and 3.4 per cent for Indians:

The World Bank Report has this to say:

“The bulk of inequality today can be explained by differences in socio-economic factors within ethnic groups rather than differences across groups. It is time to bring all Malaysians within the ambit of greater economic opportunity.”

In China

The transition towards high-quality development involved prioritising innovation, higher value-added industries, and green development.

The new emphasis is on developing sectors like technology and services, which are less resource-intensive and more sustainable in the long term. This shift is supported by policies that foster innovation, such as increased spending on research and development, and initiatives to enhance the technological capabilities of industries.

Strategic goals are also supported by China’s series of Five-Year Plans. These plans have consistently emphasised infrastructure development, technological advancement, and now increasingly, sustainability. The 14th Five-Year Plan, for example, places significant emphasis on innovation, green development, and the digital economy, which directly support the infrastructure and technological goals of the BRI.

Whereas in Malaysia

The loss of a global competitiveness in the electrical and electronics sector, and in manufacturing and exports more generally, has also given rise to concerns that Malaysia is deindustrialising prematurely, which has the potential to undermine the country’s long-term growth prospects. The weaker business sentiment from the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is not that promising either as regime’s policymakers had not undertaken adequate strategic longer-pterm future planning nor during preceding years, had any tactical short-term initiatives to solidify a firmer base towards strong growth trajectory progressively.

Instead, in 1983, two-thirds of the government total expenditure were spent to operate twenty seven of the country’s largest public entities, (see Shahriza Ilyana Ramli et al in Malaysia’s New Economic Policy: Issues and Debate, American Journal of Economics, 2013).

Department of Statistics Malaysia chief Uzir Mahidin said on February 11, 2021 that Malaysia’s fourth quarter GDP fell again by 3.4 per cent – bigger than the 2.7 per cent decline in the third quarter. Overall GDP shrank by 5.6 per cent, the biggest contraction since the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis. This sliding trend was foreseen a year ago when theedgemarket Feb 5th 2020 issue publishes a Malaysian Rating Corp Bhd (MARC) report stating that the country expects to record minus 5.6% GDP growth for 2021.

By then 4th. Dec 2020, Fitch Ratings has already downgraded Malaysia’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to ‘BBB+’ from ‘A-‘.

In China

The secret sauce of China’s policymaking process involves several key steps.

Before formalising any major initiative, the Chinese government often employs experts from think tanks, academia, and industry to conduct extensive research and feasibility studies. This helps in shaping the policy’s objectives, mechanisms, and potential impacts.

Major policies often originate from the top leadership, with significant input from the CCP’s highest echelons, including the Politburo and its Standing Committee. President Xi Jinping personally announced and championed the BRI.

For sweeping initiatives, coordination across various government bodies is crucial. This includes ministries such as Foreign Affairs, Commerce, and others that deal with infrastructure, finance, and international cooperation.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), along with other relevant ministries, also plays a crucial role in formulating the detailed policy framework. They draft plans, guidelines, and funding mechanisms.

Once formulated, the policy is queued for approval by the CCP’s central committee and the State Council. After approval, it is officially promulgated and the implementation phase begins. This phase involves local governments, state-owned enterprises, and private sector players.

Chinese policies typically undergo periodic reviews. Feedback mechanisms are in place to monitor progress and challenges, allowing for adjustments to the policy as necessary.

The BRI, as a global infrastructure and economic development initiative, is managed with a high degree of state coordination, aiming to enhance trade routes and economic ties between Asia, Europe, and Africa, reflecting China’s strategic economic and geopolitical interests. This initiative is a prime example of China’s top-down approach to policymaking, where strategic visions set by the leadership dictate policy directions and implementation mechanisms.

Whereas in Malaysia

The history of capitalism, from the beginnings of British colonialism more than half a millennium ago to our present ruling regimes of using clientel-capitalism to colonialise the minds of the unrepresented destitutes in order to retain and sustain political power, immiserising countless rakyat2 land-settleless, and to continue impoverishing the poors in order for capitalism, specifically clientel ethnocratic capital – with political fabrication and economic entrenchment of the NEP construct (James Chin, 2016) which clearly divisive to the nation’s unity and sense of belonging (Lim Teck Ghee).

The process of national economic development continuance even after independence with the implementation of a series of neoliberal economic development programs scripted with the assistance of the Development Advisory Service of Harvard (DASH) and the “consultancy advisory ” of the IMF/World Bank neoliberalism-is-neo-imperialism twin – laid the doomed foundation to a series of capital in crisis after crises, (STORM, 01 June, 2022, ethnocapital and class; STORM, 06 June 2022, ethnocapitalism in calamity crisis).

The construction of an unequal local situations and how by linking those compradore capitalism to the global system (Samir Amin, 2019) in the past and the clientel ethnocapitalism at present – where malay voters expect to, and rely on, patron-client relationships, nested within party machines, to benefit from distributive and development policies – we are beginning to see the transcendence of the capitalist system central to so many of our existing socio-economic problems, (see STORM 2024, A trunkful of dirty Linens).

In conclusion, China’s economic development over the past few decades has been characterised by adaptive planning, strategic foresight, and a remarkable capacity to recalibrate in response to changing global and domestic landscapes. From the pivot towards domestic infrastructure post-2008, to the global ambitions of the BRI, and now the focus on high-quality, sustainable development, China has demonstrated a sophisticated approach to economic strategy. This approach is underpinned by a centralised, top-down policymaking process that allows for the effective implementation of major initiatives. As China continues to navigate the complexities of the global economy, its ability to adapt and strategise will undoubtedly shape the planet’s economic trajectory for years to come.

Whereas in Malaysia, the Madani Economic Model has a cacophony of narratives and many a conversation that are soundly challenged (newleftmalaysia, February 2024).

Kari McKern

Kari McKern, who lives in Sydney, is a retired career public servant and librarian and IT specialist. She has maintained a life time interest in Asian affairs and had visited Asia often, and writes here in a private capacity.

Sun Liping 孙立平 | Tsinghua University Department of Sociology professorThe era of large-scale concentrated consumption experienced previously is basically over, said Sun in a speech on 14 April 2024. The PRC economy is in a period of contraction, and the consumer sector too is at a turning point. In conventional consumption’s current stage of gradually dividing, he said, ‘the poor cannot afford, the middle class does not dare, and the rich do not know what to consume’ has become a common impression. Given differentiating consumption, and the background of economic contraction, consumption of society as a whole faces a downward trend. Overcapacity is just a manifestation of this reality.Born in a Hebei village in 1959, Sun studied journalism at Peking University 1978–81, taking up sociology at Nankai University 1981–83. A journalist for some years, he joined Tsinghua University in 1993. He famously helped advise a younger Xi Jinping’s PhD dissertation, the resulting political capital arguably allowing him to test the limits of intellectual expression. His bestselling 1996 book, The Road to Modernisation, argued that politics had been outpaced by economic growth, brewing corruption, inequity, and unrest. With over 300 other intellectuals, Sun co-signed the ‘Charter 08’ open letter to the Party, urging political reform. He warned Caijing Magazine’s annual Forecasting and Strategy conference in 2013 of a ‘crisis of legitimacy.’ Widely reported, this caused a stir. Other notable works include Social Reconstruction (2009), China’s Political Reform (2011), and Crisis of Legitimacy (2013).

Sun Liping 孙立平 | Tsinghua University Department of Sociology professorThe era of large-scale concentrated consumption experienced previously is basically over, said Sun in a speech on 14 April 2024. The PRC economy is in a period of contraction, and the consumer sector too is at a turning point. In conventional consumption’s current stage of gradually dividing, he said, ‘the poor cannot afford, the middle class does not dare, and the rich do not know what to consume’ has become a common impression. Given differentiating consumption, and the background of economic contraction, consumption of society as a whole faces a downward trend. Overcapacity is just a manifestation of this reality.Born in a Hebei village in 1959, Sun studied journalism at Peking University 1978–81, taking up sociology at Nankai University 1981–83. A journalist for some years, he joined Tsinghua University in 1993. He famously helped advise a younger Xi Jinping’s PhD dissertation, the resulting political capital arguably allowing him to test the limits of intellectual expression. His bestselling 1996 book, The Road to Modernisation, argued that politics had been outpaced by economic growth, brewing corruption, inequity, and unrest. With over 300 other intellectuals, Sun co-signed the ‘Charter 08’ open letter to the Party, urging political reform. He warned Caijing Magazine’s annual Forecasting and Strategy conference in 2013 of a ‘crisis of legitimacy.’ Widely reported, this caused a stir. Other notable works include Social Reconstruction (2009), China’s Political Reform (2011), and Crisis of Legitimacy (2013).

You must be logged in to post a comment.