collated and compiled by the Collective on Geoeconomics

12/04/24

INTRODUCTION

KS Jomo and Ngongo have expressed that since the 2008 global financial crisis, developing nations have to borrow massively from private finance – at exorbitant interest rates – to scale funding up ‘from billions to trillions’. Indeed, servicing external debt now blocks progress whereby governments have cut back spending in line with conditions or advice from powerful foreign economic agencies as such. Onset with the global debt crisis in 1979 the transition and developing Global South economies had paid cumulative US$7.673 trillion in external debt service, see Paulo Nakatani and Rémy Herrera.

In fact, the external debts of developing and transition countries reached 29% of their GDP in 2019. The short-term debts rose to more than one-quarter of the total external debts alone.

The Global South debt even then during the same period has increased from US$618 billion in 1980 to US$3.150 trillion in 2006, according to figures published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The external debt of this group of countries, comprising 145 member states, will continue to grow throughout 2007, according to the IMF, to more than US$3.350 trillion. The debt of the Asian developing countries alone could rise to US$955 billion, even though they have already repaid, in interest and capital, far more than the original amount due in 1980!

Malaysia 2019 external debt was RM$231225.9 million, (Asia Development Bank, External Debt Outstanding in Asia and the Pacific, Asian Development Outlook, April 2020).

According to a report to the Asian Development Bank, in September 2020, by Donghyun Park, Arief Ramayandi, Shu Tian stating inter alia that borrowing heavily for fiscal stimulus packages to support growth and provide relief for vulnerable groups whilst at the same time, private companies and households may be forced to borrow more to survive the economic impact of COVID-19…..In addition, the economic downturn challenges their capacity to service their existing debts. Therefore, despite widespread concerns about the current escalation of public debt and its sustainability, we should not lose sight of the potential risk from possible surges of private debt…..

Coupled with a weakening economy, already, as late as July 2023, a IMF Report has projected that under its baseline forecast, growth will slow from last year’s 3.5 percent to 3 percent this year and next – a 0.2 percentage points. Our MIDF Research data have maintained its forecast that Malaysia’s GDP growth would moderate at 4.2% in 2023 (2022: 8.7%), weighed down by uninspiring external trade performance as real export of goods is predicted to contract by 2.8% (2022: +11.1), reflecting weakness in regional and global demand.

Furthermore, the national household debt-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio had already surged to a new peak of 93.3% as at December 2020 from its previous record high of 87.5% in June 2020, according to Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM).

Malaysia National Government Debt reached 255.4 USD bn in Dec 2023, compared with 246.4 USD bn in the previous quarter. Malaysia Government debt accounted for 64.3 % of the country’s Nominal GDP in Dec 2023, compared with the ratio of 63.8 % in the previous quarter; see csloh, Destined to Debts.

We shall define the Global debt as borrowing by governments, businesses and people. Presently, it is at dangerously high levels. In 2021, global debt reached a record US$303 trillion, a further jump from what was record global debt in 2020 of US$226 trillion, as reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its Global Debt Database,21 Dec 2023.

The IMF must do more to support low-income countries and fragile states, Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said on Tuesday at the Center for Global Development (CGD).

Speaking with Masood Ahmed, CGD President, Georgieva called for the Fund to be more representative of the global economy, with a better balance between advanced economies and the voices of emerging and developing countries. She also expressed the need to help countries build resilience to a more shock-prone world.

Georgieva said she sees two equally important tasks for the Fund: “To ensure that we have the financial capacity to operate, and support vulnerable middle-income countries and low-income countries……And to bring our membership together….Despite all the difficulties in cooperation, we will work towards consensus on those issues on which the future of our children and grandchildren depend,” Georgieva said. She also explained the IMF’s role in its work on climate.

During a subsequent conversation with World Bank Group President Ajay Banga at an event on support for low-income countries, Georgieva shared more of the Fund’s thinking. For low-income countries to reduce vulnerabilities and achieve a sustainable and meaningful rise in income levels quickly, it will take the countries themselves to do more to build the strength of their economies, and the international community to be a reliable partner, she said.

“We see that those [countries] that are doing better are countries with strong institutions, rule of law, transparency, and less corruption, and building those strengths is something no one but the countries can take on.”

Managing The Debts

Hidden Debt Hurts Economies. Better Disclosure Laws Can Help Ease the Pain.

Alissa Ashcroft, Karla Vasquez, Rhoda Weeks-Brown

Domestic laws need updating to ensure that public obligations are transparent

April 2, 2024

If efforts to address record global public debt are to leave no stone unturned, then weak disclosure laws warrant deep scrutiny. Hidden debt is borrowing for which a government is liable, but which is not disclosed to its citizens or to other creditors. And while this debt—by its nature—is often kept off the official government balance-sheet, it is very real, reaching $1 trillion globally by some estimates.

While these undisclosed obligations are not large when compared to global public debt topping $91 trillion, they pose a growing threat to low-income countries, already highly in debt with annual refinancing needs that have tripled in recent years. The problem is even more pressing amid higher interest rates and weaker economic growth. Accountability, too, is imperiled without accurate information about the extent of borrowing, which heightens the risk of corruption.

These potentially dire consequences can be avoided by strengthening domestic legal frameworks. Our new paper, The Legal Foundations of Public Debt Transparency: Aligning the Law with Good Practices, presents findings from a survey of 60 countries that examined vulnerabilities and loopholes in national laws that hinder transparency.

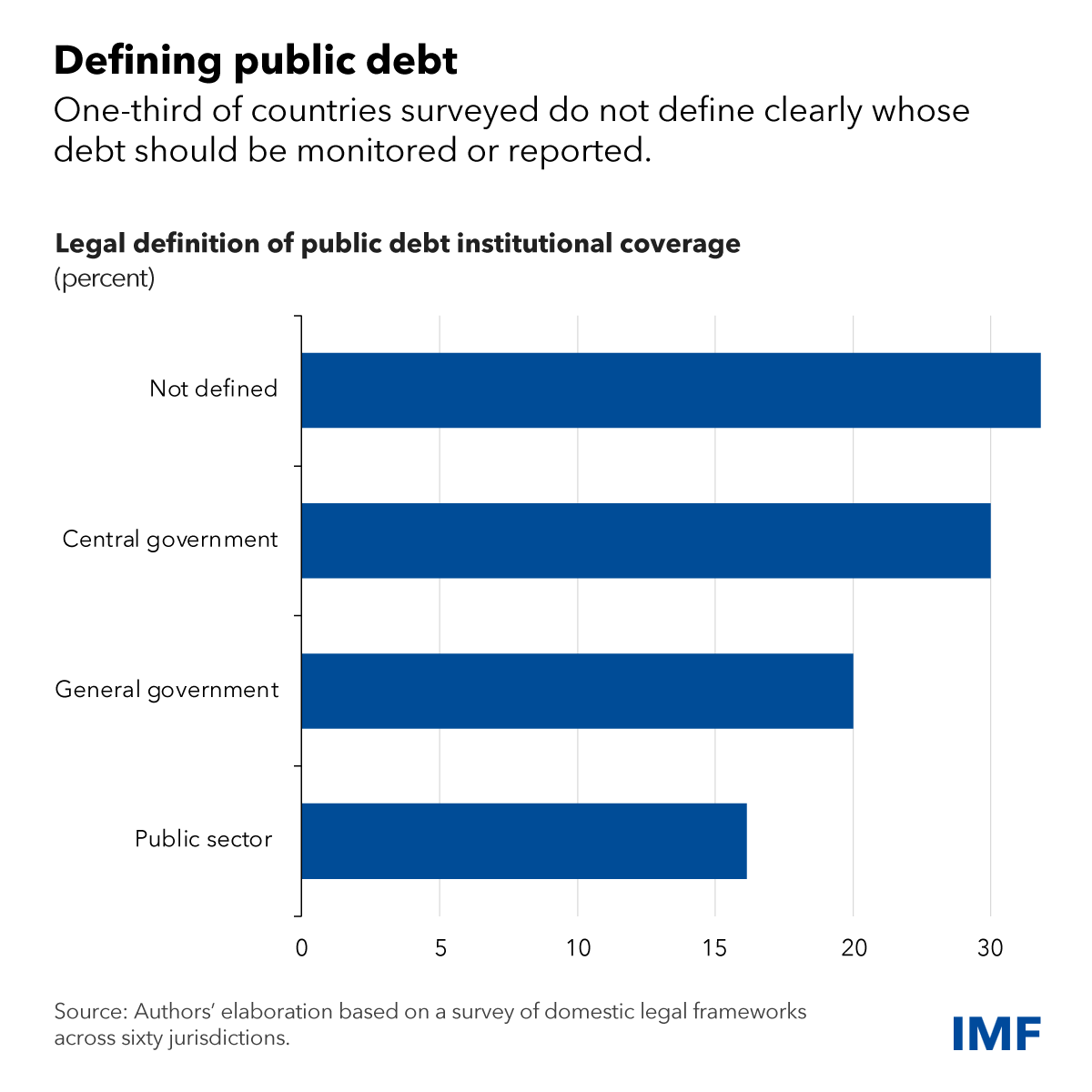

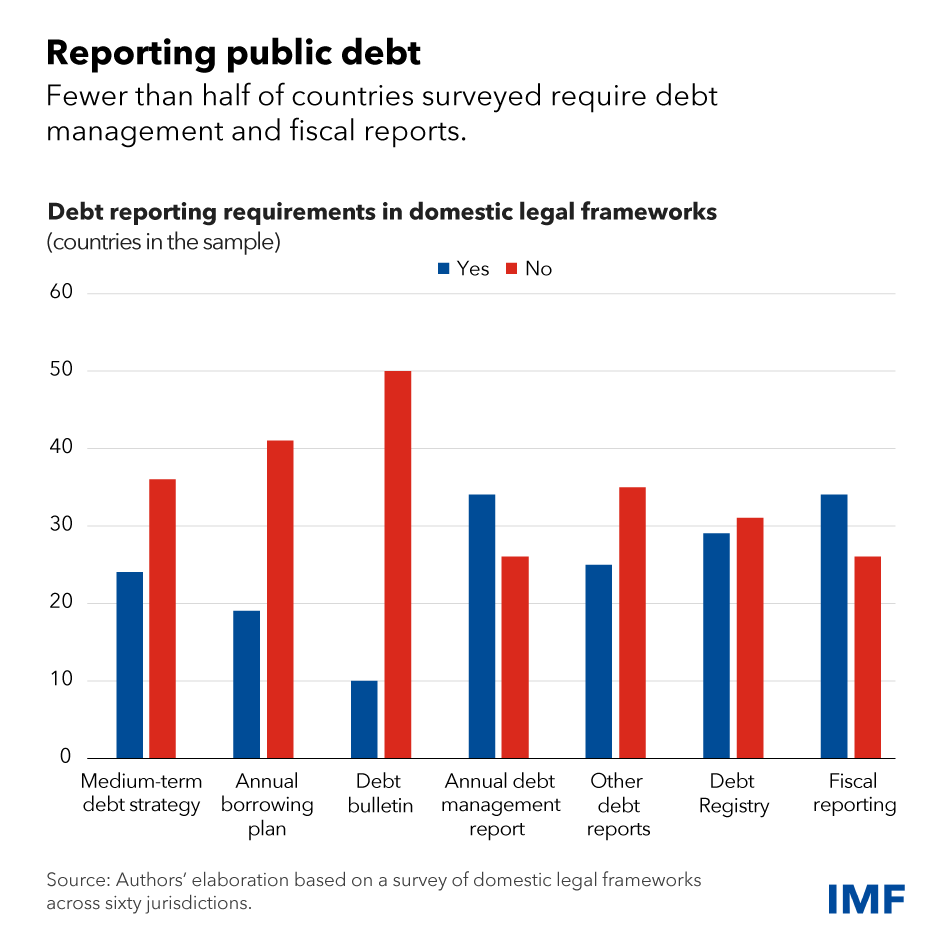

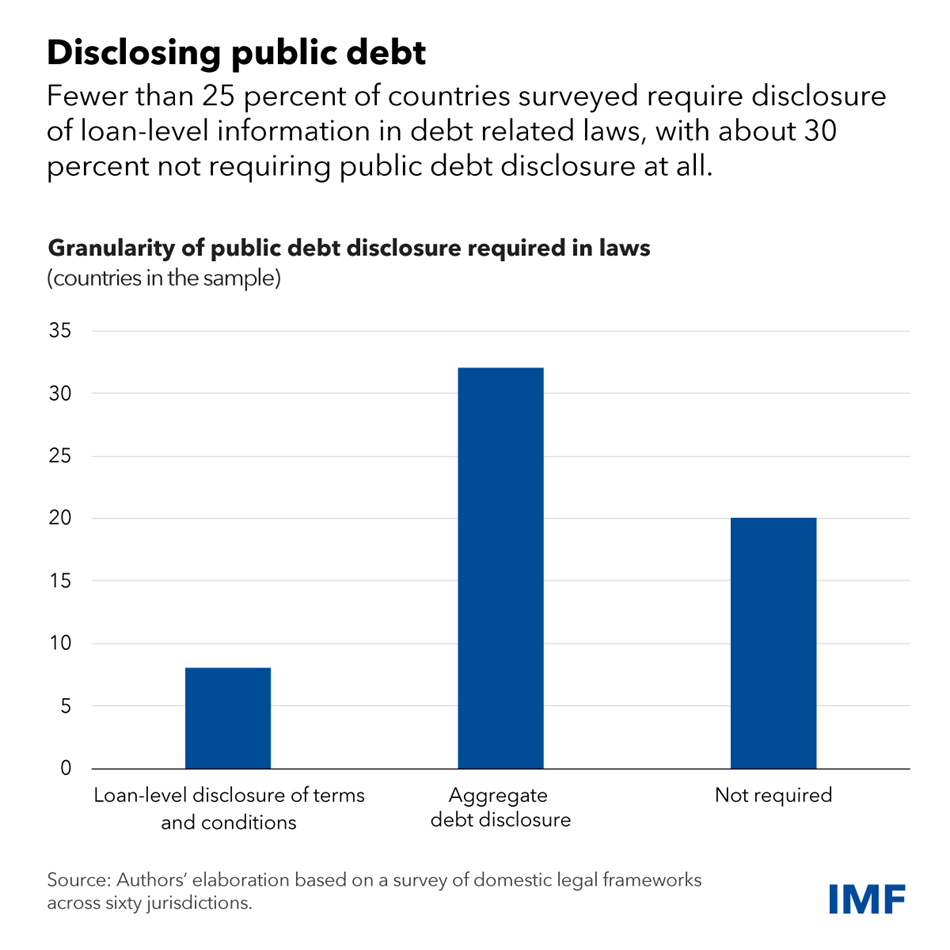

Building on a July 2023 paper, our new research shows that fewer than half the countries surveyed have laws that require debt management and fiscal reports, while less than a quarter require disclosure of loan-level information—key legal features for facilitating transparency. We also identify four noteworthy vulnerabilities in domestic laws that enable debt to be hidden: a narrow definition of public debt, inadequate legal requirements for disclosure, confidentiality clauses in public debt contracts, and ineffective oversight.

Definition

In many countries, a narrow definition of public debt, in one or in multiple laws, permits some forms of sovereign debt to escape oversight. We recommend that the definition of public debt be broad and comprehensive, meaning that it should capture arrears, derivatives and swaps, suppliers’ credit, and assumptions of guarantees as well as loans and securities. The definition should also cover extra budgetary funds, public trust funds (pension funds, for example), and special purpose vehicles.

A good example is found in Ecuador, which pursued legal reform in 2020 to ensure that short-term financing instruments—such as securities or treasury paper with terms of less than one year—were included in debt calculations and statistics. Other good examples include the legal definitions used in Ghana, Jamaica, Rwanda, Thailand and Vietnam, all of which encompass multiple types of debt instruments.

Disclosure

Second, across the globe, legal requirements for debt disclosure are inadequate. A strong legal basis is crucial to signal that there is a clear requirement to report debt data in a manner that is both timely and relevant for policy analysis, transparency and accountability. Strong reporting laws are found in in Benin, Kenya and Rwanda, which define both public debt reporting requirements and the timeframes for these reports.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality in public debt contracts directly hinders transparency. Across the globe, few laws regulate (and limit) the confidentiality of public debt, which hands policymakers wide discretion to label such contracts confidential for national security or other reasons. This is exacerbated by the fact that current debt-related international standards and guidelines provide limited guidance on how to tackle confidentiality issues.

We recommend that the law tightly define exceptions to disclosure and the scope of confidentiality agreements. Legislative oversight and other safeguard mechanisms such as administrative or judicial remedies should also be spelled out in the applicable legal provisions. Laws in Japan, Moldova and Poland are among the few that authorize legislative or parliamentary oversight of confidential information.

Oversight

The disclosure of public debt may also be inhibited where there is ineffective oversight governance by legislatures and supreme audit institutions (national government audit institutions), which are all important guarantors of accountability. Legislative bodies must be able to monitor and scrutinize public debt on behalf of the people, and they need to have staff able to read and grasp highly technical reports.

Several legislatures have a committee system—such as committees on the budget and public accounts—which allows for specialization among legislators. An example is in the United States, where the Treasury Secretary is required by law to send the annual public debt report not to Congress as a whole, but to two specific committees—House Ways and Means and Senate Finance. We also recommend that laws provide supreme audit institutions with the authority and the necessary powers to monitor and audit government debt and debt operations.

IMF role

Debt transparency not only benefits countries directly, but it is also essential for the work of the IMF. Hidden and otherwise opaque forms of debt make it more difficult for the Fund to fulfill its core mandate in a number of ways. For example, collateralized loans, novel and complex forms of financing, and confidentiality agreements make it difficult for the IMF to accurately assess a country’s debt and help bring its economy back on track.

Thus, the Fund works to bring the benefits of debt transparency to countries directly through technical assistance and also addresses the issue in our program engagements.

Well-designed laws make it harder to hide debt. But there are not enough of these laws on the books, despite their demonstrated benefits. Given the critical importance of getting transparency right, countries and their international partners must push for reforms to improve domestic legal frameworks, which in turn benefits both borrowers, legitimate creditors, and the system more broadly. Turning stones has never been more important.

— Kika Alex-Okoh contributed to this blog.

ADDENDUM

By way of confronting China with the peak paradigm by dispelling “Peak China” myths and affirming China’s development trajectory (john ross; Habib al Badawi; the diplomat; CfR; The East is Rising, the West is Declining {东升西降}) is much a discourse that China only wants to export its labour, that China only wants to grab the world’s resources, etc., and is engaged in debt diplomacy suppressing emerging economies in their development endeavours. The Johns Hopkins University’s China-Africa Research Initiative website has exceedingly valuable statistics and reports and blogs about this matter; this site also has a discussion on the China Trap Diplomacy whereas PRC firms are being told to reduce their financial exposures in overseas jurisdictions that could move to seize assets; and there is a good roadmap since the seizures of Russian assets after the invasion of Ukraine; read Counter Sanction Strategies that China Can Learn from Russia, Ding Yifan; Countering Western Sanctions, Yi Yan.

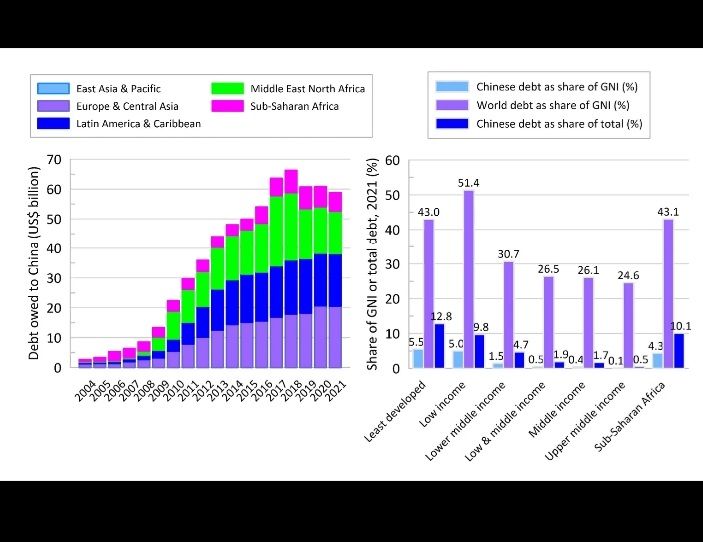

Looking at the chart below:

This chart actually plots Chinese credit, so it’s the debt of the rest of the world, the developing world, to China. And the chart on the left simply indicates the way in which debt owed to China has, of course, increased over the course of time as a result of Chinese development assistance and China’s lending, especially to parts of the Global South; read RISE OF CHINA AND DEMISE OF CAPITALIST WORLD ECONOMY.

One of the very striking things about China is that a large share of its lending is, in fact, to very low income countries. It lends more to the least developed countries in the world than do the multilateral institutions and do the OECD group.

If you see the least developed countries, their total debt to the rest of the world is 43% of their gross national income, which is, nearly one half, a very substantial share. Of that debt, the share owed to China is only 5.5%. And Chinese debt amounts to 12.8% of the total.

China’s share of GNI is 4.3%, and its share of the total debt of sub-Saharan Africa is 10%. So these claims about a debt trap are, in a sense, simply do not stand up empirically.

RELATED

Indebtedness through and by neo-imperialism