18th September 2022

1 INTRODUCTION Sarawak, a state in Borneo, exhibits slower development but rapid environmental degradation.

Sarawak, a state in Borneo, exhibits slower development but rapid environmental degradation.  The World Bank Monitor June 2022 Report “Catching Up: Inclusive Recovery & Growth for Lagging States”, points to 5 states, namely Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, Sabah, and Sarawak, with the lowest average income and highest incidences of poverty.One of the priorities under the 12th Malaysia Plan was to multiply the growth of less developed states to reduce the regional development gap.Sarawak is attempting her economic development programs sustaining ahead with a better performance.

The World Bank Monitor June 2022 Report “Catching Up: Inclusive Recovery & Growth for Lagging States”, points to 5 states, namely Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, Sabah, and Sarawak, with the lowest average income and highest incidences of poverty.One of the priorities under the 12th Malaysia Plan was to multiply the growth of less developed states to reduce the regional development gap.Sarawak is attempting her economic development programs sustaining ahead with a better performance.

2 ECONOMIC SURGES

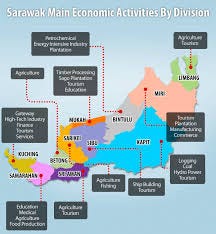

Sarawak’s economy recorded a positive 2.9 percent in 2021 – an improvement from a negative growth of -6.8 per cent in 2020 – with an economic value of RM$131.2 billion.In 2021, Sarawak retained its position as one of the top six contributors to Malaysia’s overall national gross domestic product (GDP) growth. According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), Sarawak contributed 9.5 per cent to Malaysia’s total GDP growth. Selangor lead of the national economy with a contribution of 24.8 per cent.The Service Sector is the largest contributor to Sarawak’s economy with a contribution of 35.9 per cent followed by the the manufacturing sector which contributes 28.4 per cent and the mining & quarrying sector with a contribution of 21.1 per cent. The agriculture sector and the construction sector respectively contributed only as much as 11 and 3.4 per cent.

According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM), Sarawak contributed 9.5 per cent to Malaysia’s total GDP growth. Selangor lead of the national economy with a contribution of 24.8 per cent.The Service Sector is the largest contributor to Sarawak’s economy with a contribution of 35.9 per cent followed by the the manufacturing sector which contributes 28.4 per cent and the mining & quarrying sector with a contribution of 21.1 per cent. The agriculture sector and the construction sector respectively contributed only as much as 11 and 3.4 per cent.

For the GDP per capita, the 13 states and two federal territories in Malaysia registered an increase in the GDP per capita value compared to 2020, with seven states recording a GDP per capita value above the national level of RM$47,324, namely the Federal Territory (FT) of Kuala Lumpur (RM$124,232) and FT of Labuan (RM$78,032), Penang (RM$58,527), and Sarawak (RM$57,635). Further, upon improving trade performance, Sarawak registered double-digit growth in year 2021 as compared to the previous year.

Further, upon improving trade performance, Sarawak registered double-digit growth in year 2021 as compared to the previous year.

This growth was driven by robust external demand and higher commodity prices – valued at RM$150.9 billion – where total trade increased by 27.8 per cent with a surplus of RM$52.7 billion, an increase of 45.1 per cent.Products wise, the surge in exports was contributed mainly by liquefied natural gas (RM$6.3 billion, 21.8 per cent), palm oil (RM$3.9 billion, 35.5 per cent), crude petroleum (RM$3.3 billion, 45.5 per cent), aluminium (RM$2.7 billion, 53.1 per cent) and condensate & other petroleum oil (RM$2 billion, 64.3 per cent).

3 ECONOMIC CLIENTELSHIP At a time when there are 84 “sick projects” identified in Sarawak; and that there are plans to rescue contractors, concessionaires and capital clientels with proposals that these projects would be re-tendered – only point to ulterior and fortunous opportunities for these clientel-players to replenish once again their capital accumulation. Some of the ongoing mega construction projects embrace the Pan Borneo Highway, Engineering, Procurement, Construction, Installation and Commissioning (EPCIC) of the Kasawari Gas Development Project, the Baleh Hydroelectric project, the EPCIC of Jerun Development Project, the construction of the Sarawak Coastal Road Package. There are other proposed constructions, including the completion of Muara Lassa Bridge, Mukah, and the Sawarak Water Grid Programme phase 2 in Miri.All these big-ticket projects are for the comprador capitalists as the ruling regime in Sarawak has already committed RM$64bil for various efforts to further develop basic infrastructure with allocated state budget.In June 2022, the state government had said that 7,530km of new roads would be built to connect all rural areas, while 3,487km of roads must be upgraded or rehabilitated.It needs to be said that CMS is the sole cement manufacturer in the state while KKB, an associate company of CMS, is involved in civil construction and steel-related manufacturing. The Sarawak Economic Development Corp (SEDC) holds 10.7% in KKB through a private placement in December 2021.These corporate inter-linkages are one aspect of ethnocapital still in dominance in Sarawak’s economy; not surprisingly, many of these entities are involved in the Pan-Borneo Highway project (read: STORM, Taken for a Ride), and related state development projects.

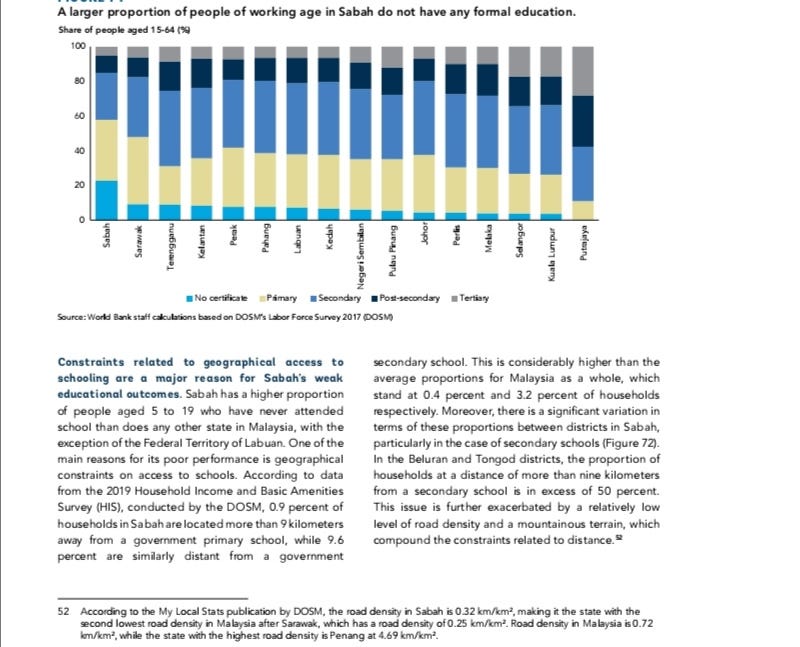

4 ECONOMIC DEFICIENCIES A] The Education sector, like in Sabah, has been in attainment deficiency:

A] The Education sector, like in Sabah, has been in attainment deficiency: A higher proportion of young generation do not have a certificate or obtain a primary schooling, and worst, many of the youngsters (age: 5-19) just do not attend schooling – not dissimilar to the situations in her neighboring state of Sabah.

A higher proportion of young generation do not have a certificate or obtain a primary schooling, and worst, many of the youngsters (age: 5-19) just do not attend schooling – not dissimilar to the situations in her neighboring state of Sabah. Since Education is knowledge, and skills that should be fully utilised, to their current work. However, owing to the lack of schooling facilitates, a majority of “employed graduates” are in the semi-skilled category which accounted for 32.9 per cent (1.50 million persons). They were largely employed as Clerical support workers (14.4%), followed by Service and sales workers (10.8%) and Craft and related trades workers (4.2%).

Since Education is knowledge, and skills that should be fully utilised, to their current work. However, owing to the lack of schooling facilitates, a majority of “employed graduates” are in the semi-skilled category which accounted for 32.9 per cent (1.50 million persons). They were largely employed as Clerical support workers (14.4%), followed by Service and sales workers (10.8%) and Craft and related trades workers (4.2%).

B] A study by Assistant Professor of Communication at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota, Dr Nuurrianti Jalli, has found dissatisfaction among 67.1 per cent or 385 users over Internet access in East Malaysia due to weak, slow, and unstable connectivity – with some being unable to log in at all; read 18-year-old Veveonah Mosibin internet-surfing challenging episode in STORM, A Digital Knight. “Telecommunication Tower” in a village near Miri

“Telecommunication Tower” in a village near Miri

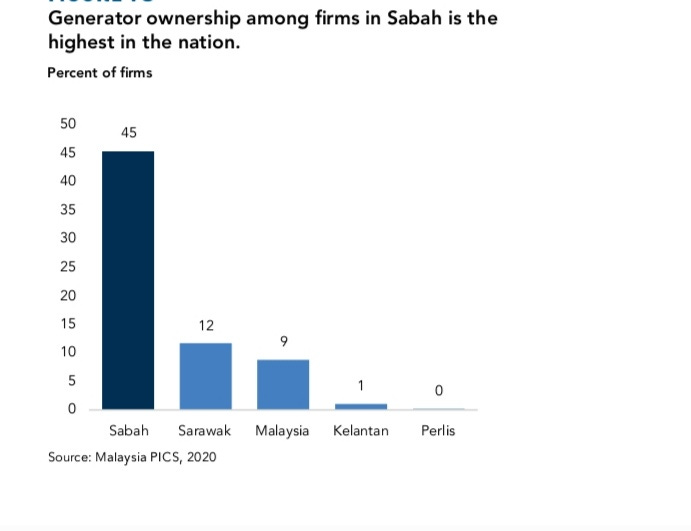

C] Infrastructure – simple basics like electricity and water are not easily available, especially in the highland interiors. Also, not unlike in Sabah, there is community-sharing in the use of generators where diesel fuel to operate them are expensive to ferry across turbulent river currents. A research on Indigenous community preferences for electricity services: Evidence from a choice experiment in Sarawak, Malaysia has indicated that the most value was placed on the operator-model underpinning the provision of electricity services and that there was a strong preference for a community-based model over a utility-based model. Interestingly, the researched results suggest that the preference for a community-based operator model may be related to the experience of using electricity for productive uses. The study has demonstrated the importance of social and institutional challenges in providing electricity services to indigenous communities, and highlight the need for the state utility to engage with indigenous communities to overcome these challenges.5 ECONOMIC NATIONALISMOutstanding issues pertaining to eradicate Sarawak economic underdevelopment, in summary:

A research on Indigenous community preferences for electricity services: Evidence from a choice experiment in Sarawak, Malaysia has indicated that the most value was placed on the operator-model underpinning the provision of electricity services and that there was a strong preference for a community-based model over a utility-based model. Interestingly, the researched results suggest that the preference for a community-based operator model may be related to the experience of using electricity for productive uses. The study has demonstrated the importance of social and institutional challenges in providing electricity services to indigenous communities, and highlight the need for the state utility to engage with indigenous communities to overcome these challenges.5 ECONOMIC NATIONALISMOutstanding issues pertaining to eradicate Sarawak economic underdevelopment, in summary:

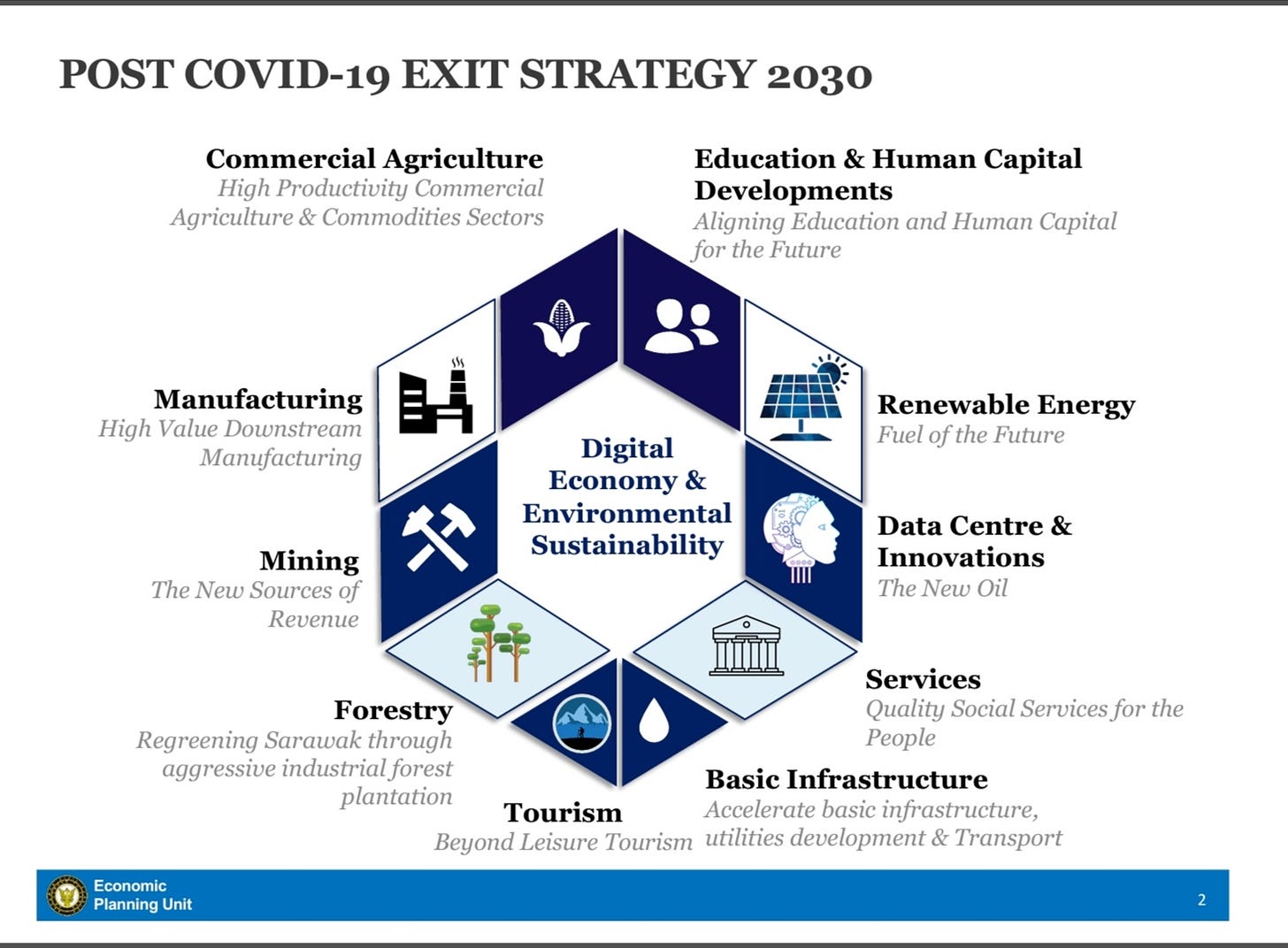

i) overall restructuring the education system in the state not only in repairing and modifying dilapidated rural schools, and provision of adequate teaching staff therein – to be funded by oil and timber extraction premiums to provide scholarships and loans to students pursuing their tertiary education so that human resources are geared towards the Industrial Revolution 4.0 and the digital and cyber analytics workplace environment in marketspace of the future. Higher Education Ministry had stated that nation-wide there were 197,000 unemployed graduates in 2021, the highest numbers having degrees in social sciences, business and law, with the DoSM Labour Market Review for the first quarter 2022 showing a skill-related under-employment of 37% mismatch between occupations and qualifications, (thesun, 15/09/2022).

Higher Education Ministry had stated that nation-wide there were 197,000 unemployed graduates in 2021, the highest numbers having degrees in social sciences, business and law, with the DoSM Labour Market Review for the first quarter 2022 showing a skill-related under-employment of 37% mismatch between occupations and qualifications, (thesun, 15/09/2022).

Malaysia’s politico-economic – and Sabah with Sarawak economic underdevelopment – must be rectified so that wealth will be shared more equitably by the bumiputera and every citizen regardless of race and religion, and encouraged to embrace – and to include the Orang Asal of the country’s First People – towards our wholesome economic nationalism development together as One People, One Nation, One Progress.

ii) United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, United Nations, 2008 declaration identifies an “urgent need to respect and promote the inherent rights of indigenous peoples which derive from their political, economic and social structures and from their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories and philosophies, especially their rights to their lands, territories and resources.”

Specifically,

Article 28 addresses how indigenous peoples are entitled to restitution or compensation with respect to “confiscated, taken, occupied, used, or damaged” customary land.

Additionally, Article 10 explicitly bans the forced removal of indigenous populations from their land, recognizing that relocation can only occur with free, prior, and informed consent and equitable compensation or compensation with respect to “confiscated, taken, occupied, used, or damaged” customary land.

Nicholas has recommended a shift in the mindset of JAKOA and politicians to actively advocate for the Orang Asal communities, remove prejudicial practices, and re-educate the public on Orang Asal issues.Given that many of the Orang Asal’s prevailing challenges stem from their lack of customary land ownership, systemic change must come at legislative level to implement a truly land reform movement for marginalised natives with titled land for all, (read: STORM, 2020, The Development of Underdevelopment).

iii) There is a need to transform and innovate the healthcare system, with better healthcare delivery – including coverage for outlaying native communities – and accountability systems, with consideration the impact of globalisation has changed the epidemiology of emerging and epidemic-prone diseases. Created to be is an unified system of clinics connected to the family doctor-nurse teams serving at community-base level

iv) Implementation therein, and the acceleration thereof, in infrastructure provisions (clean water, continuous electricity, accessible land and riverine routes) so that the balance growth of Sarawak economies are integrated in bridging the rural-urban divide

v) From a post-independence neo-colonial economy to a DASHarvard’s managed monopoly-capital economy sustaining the continuance of a neo-liberal economic development, we are witnessing the development of underdevelopment in Malaysia today between unequal economies in peninsula Malaysia and the client states of Sabah and Sarawak.It was only in the late 1965 that the country asserted an economic nationalism posture with a Dawn Raid on the British agency houses, but unfortunately this corporatisation take-over inevitably became part of an ethnocratic economic realignment to the New Economic Policy positioning with all its negative ramifications. Now it is the turn of Sarawak and Sabah to take a midnight raid to reclaim the rights in the MA63 Malaysia Agreement 1963 so that in a truly developmental effort by a new generation of progressive leaders attuned to equal sharing of community resources for the due distributed benefits for every rakyat2 in their owned homeland.