26/01/24

PROLOQUE

Malaysia is at a juncture in its politico-economic path crashing into fractious politics headlong on an inequity route with an expanding B40 lower-income class, (mef.org 2023). The socio-economic situations are becoming precarious. This is because of a stagflation risk arising amid sharp slowdown in growth that is accompanied by an accelerated inflation runaway globally, (World Bank, Global Economic Prospects, June 7, 2022) as confirmed by the Bank of International Settlements in its Annual Economic Report, 26 June 2022, and amid subdued external demand could only edge up to 4.3% GDP in 2024 (World Bank Malaysia Economic Monitor 2023), though Standard Chartered gave a favourable 4.8% of GDP; while the Madani Malaysia model is trekking slowly along an uneven economic development track that is strewn with global geoeconomic uncertainties and internal socio-economic instability.

Could and would the enlargement, and deepening, of the infrastructural platforms accompanying an artificial intelligence regime therein salvage the state of a nation or the adoption of such advance technology savages the country with further neo-imperial penetrative wounds while accompanying digitalised colonisation process?

I] INTRODUCTION

Standing at a crossroads of techno-capitalism and neo-imperialism, artificial intelligence (AI), with its potential promise though has profound existential problems to the Global South because advances in AI originated in wealthy nations of the Global North — developed in those countries for local users, using local data. Over the past several years, Columbia’s Daniel Björkegren and Berkeley’s Joshua Blumenstock for Finance & Development have conducted research with partners in low-income nations, working on AI applications for these countries, users, and data. However, AI systems require investment in knowledge infrastructure, especially in emerging and developing economies, where data gaps persist and the poor are often, if not, always digitally underrepresented. Besides, developing nations typically ill-afford such expensive large-scale deep neural networks infrastructure using expensive AI-driven application software.

Afterall, Artificial Intelligence (AI) leverages computers and digital machines to mimic the problem-solving and decision-making capabilities of the human mind.

Frequently, the techno-optimism in the advanced economies (Goldman Sach 2023; and, according to a Bloomberg’s PwC Report, AI would boost the global GDP to US$15.7 trillion by 2030) is at odd with Global South economic development outcomes, (Daron Acemoglu Simon, IMF); where AI technology is in likelihood to destroying jobs and displacing workers, (Andrew Berg Chris, IMF); or where the building block for AI governance is weak (Ian Bremmer, Mustafa, IMF) on system design, project implementation and subsequent operational processes. Indeed, Artificial Intelligence could well widen the gap between rich and poor nations, (Alonso, Kothari and Rehman, IMF Blog Dec 2, 2020; IMF 2018).

Then, on this understanding, to duly acknowledge that in emerging markets such as India, where agriculture plays a dominant role, less than 30 percent of employment is exposed to AI. Brazil and South Africa are closer to 40 percent. In these countries, the immediate risk from AI may be reduced, but on the other hand, there may also be fewer opportunities for AI-driven productivity boosts, (Gopinath, Harnessing AI for global good).

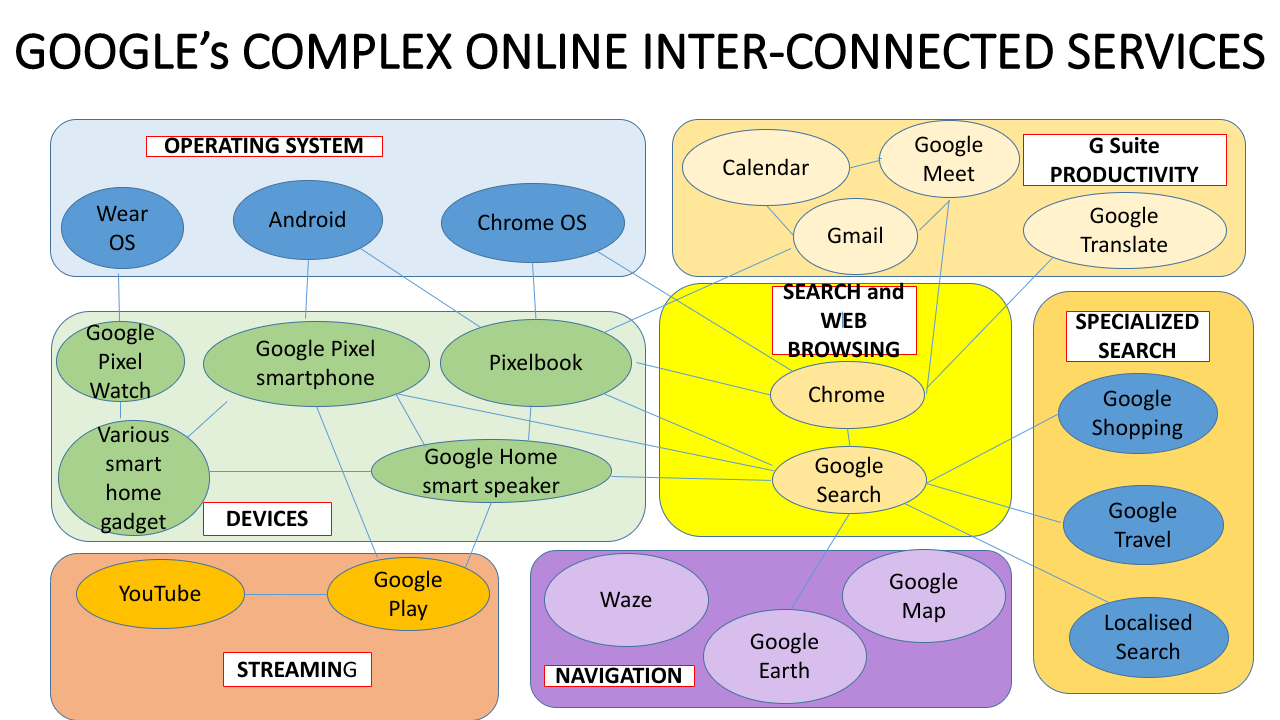

Secondly, Silicon Valley corporations are taking over the digital economy in the Global South with little notice, or for those encouraged by the World Bank – but short-circuiting the rakyat2 – as in Malaysia,(WB 2021; MEM 2023), the domestic infrastructural platform ecosystems are already consolidated by the Global North monopoly-capital Big Tech, (STORM 2023). In case country South Africa, Google and Facebook dominate the online advertising industry, and are considered an existential threat to local media. Uber has captured so much of the traditional taxi industry that drivers have been petrol bombed in the “South African taxi wars”. Similar battles have broken out in Kenya, (al jazeera, 2019).

Netflix is not only pulling subscribers away from local television services, but are buying up content in Africa. While in India, Facebook was forced to cancel its “Free Basics” programme that gave the social media giant control over the Internet experience on mobile phones, she was able to retain its influence in countries like Kenya and Ghana.

This is known as digital colonialism where once former Colonial powers deployed their infrastructural domination in ports, waterways, and railroads across their vast empires, only that at present day neo-colonialism is continued through digital routers and data servers.

The digital infrastructural platforms are not unlike colonial ‘forward movement’ activities where lands are waiting to be discovered and conquered. Whoever gets there first, and holds fast and tight, shall get their information server-riches. The infrastructural platform kings (colonial-feudal lords) positions themselves above users (the colonised), and their data surfing activities (serfs’ farm cultivation), thereby giving them overwhelming privileged access (lordship) to record and retrieve (dictate and dominate) endusers (the serfs) as and when demanded (as surplus value expropriation) under an information-commodity chained monopoly-capital environment (via routers and cloud servers) .

Thirdly, tech capital flows unencumbered trans-borders where new ecosystem of digital platforms has emerged over the past decade that is transforming the very structures of capitalism. This new business model of large monopolistic digital platforms are capable of extracting immense amounts of data overwhelming legacy enterprises and suppressing labour empowerment, (see Paul Langley and Andrew Leyshon, 2020). This is “netarchical capitalism” , where infrastructure is “in the hands of centralized privately owned platforms”, (Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism, 2017).

Information and infrastructural platforms have empowered a new kind of ruling class. Through the ownership and control of information, this emergent class dominates not only labour but capital. It is not just tech companies like Amazon and Google; even Walmart and Nike can now dominate the entire production chain through the ownership of brands, patents, copyrights, and logistical systems – all “soft” elements than physical end-products, all accumulated through financialization capitalism through a neo-imperialism monopoly-capital pathway.

Digital technology has already indeed transformed the world economy; the decade leading up to 2019, the largest 100 firms in the world had increased their total market capitalisation by US$12.7 trillion. A third of that increase (US$4.2 trillion) can be accounted for by just seven firms: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft (the famous quintet ‘FAAAM’), Tencent and Alibaba. The aggressive rally of tech stocks during the COVID-19 pandemic had given due recognition that an entirely new model of value creation was enabled, and primarily all enhanced, by digital technology.  Tech companies are the new empires of today: Alphabet revenue surpassed Hungary’s GDP, Facebook employs over 15000 content moderators around the world, and Microsoft has built data centers in nearly every corner of our planet, with Google global dominating the infrastructural platform corporate businesses.

Tech companies are the new empires of today: Alphabet revenue surpassed Hungary’s GDP, Facebook employs over 15000 content moderators around the world, and Microsoft has built data centers in nearly every corner of our planet, with Google global dominating the infrastructural platform corporate businesses.

Hidden from view, but the most vital part of this Techno-capitalism identity is the convergence of fibre-optics under the strategic blue waterways and sea corridors around the world that connected the various routers and artificial intelligence neural-networked database in a singularity ecosystem:

Since raw data, processed information and uninterrupted communications are of prime importance in a globalised geoeconomic environment, the installation, repairs and maintenance of the underwater cables in the country are with these infrastructural platform players of tech giants such as Google, Amazon and Microsoft, and the national internet exchange body, Malaysian Internet Exchange. However, the conflicting battle between national sovereignty and Global North financialised monopoly capitalism only accentuate the brute reality of intrusive Techno-capitalism and its digitalised colonisation process, (STORM 2023, marine-cabotage-under-netarchical-capitalism; whereas, the neo-imperialism aspects on 5-Eyes, Unmanned Underwater Vehicles, USVs, and the geopolitics involving AUKUS and QUAD are covered in firesstorms, August 2022).

II] TECHNO-CAPITALISM

With the emergence of new capital, the capital-endowed new ruling class extracts the content capacity of information to route around worker and social movements to barricade labour participation and involvement. The emerging ruling class is the digital feudal lords overseeing a common of digital infrastructure where bands of peasantry-labour are the digital gig-slaves to be exploited. In this digitalized business model, returns do not diminish as businesses scale up but increase exponentially. Geared towards the exploitation of digital-dehumanised workers (Yanis Varoufakis) whence they are mere interfacing intermediary conduits to big data storage and retrieval by infrastructural platforms powered by artificial intelligence nowadays that are so overwhelmingly powerful in exploiting surplus value of labour relentlessly, and with brutal efficiency, it is the accumulation of capital, through and thoroughly (Ursula Huws, Labor in the Global Digital Economy: The Cybertariat Comes of Age, 2014; read a case country of digital knights in a kingdom of infrastrutural thrones, in STORM 2020; Big Tech and Large Gig-Labour: STORM, June 2022 and Digital Labour: STORM, December 2020 ; and a related essay on Techno-feudalism, in STORM, August 2022).

It is also becoming but unbelieving for foreign investors – specifically Global North monopoly-capital corporates – not wanting to partner local expertise to provide support and services from their financialised capital. These Global North entities insist on retaining their monopoly investments, especially on the infrastructural platforms varied ecosystems.

As an instance, the country needs local expertise to ensure our national undersea cables are well maintained and not to be wholesomely dependent on Global North monopoly-capital corporations on an unequal economic and inaccessible technological exchanges. That the international infrastructural platforms had once threatened to withdraw in cooperating with the national digital economic aspiration is uncalled for.

At a time of an epidemiological-economic-ecological polycrisis, many national banks accelerated the monetary flow – and the resulting wave of liquidity – leading to substantial increases in corporate wealth in many developed and advanced economies, whereas the emerging and low income economies face external debt distress compounding poverty of the global poors, (World Bank 2022; STORM, 2022, Wealthy Rich, Poverty Poors). As a result of falling income levels, widespread employment losses and widening fiscal deficits, (UNCTAD 2020) – a rakyat-oriented governance should not allow appearance of vulture-capitalism in the guise of infrastructural platforms be roaming the waves of high blue waterways as predatory pirates, (STORM, January 2023) when there is a sea of opportunities for the country in laying submarine cables, too:

And even as the Covid-19 pandemic coursed through the world’s population, Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta Platforms – were able to rake in US$255.7 billion in profits in 2022, or 16.4% of the Fortune 500’s total earnings for the year, (Fortune, June 2023). Their capital accumulation revealed grotesque class and racial inequalities and the gross lack of public investment and preparation, (monthlyreview).

To compound developmental efforts, transnational corporations (TNCs) exploit legal loopholes in low-income countries (LICs) to avoid or minimize tax liabilities by applying a practice known as ‘base erosion and profit shifting’ (BEPS). Under such circumstances, tax havens collectively cost governments US$500–600B yearly in lost revenue. Low-income countries will lose some US$200B – more than even the foreign aids of US$150B that they received annually, (Jomo, June 2022). Indeed, TNCs-supported agents, and lobbies, have blocked the International Tax Cooperation initiative, (Anis Chowdhury and Jomo Sundaram, June 2021) to ensure tax equity and revenue intake equality, (see also STORM 2023, International Corporate Taxes – issues of misdeeds).

And whatever financial assistance as rendered, the World Bank category of aid only encourages governments to enable illicit financial outflows to offshore tax havens – where such tax havens could cost countries US$4.7 trillion over the next decade, (icij 2024) – reducing capital controls, thus draining further precious foreign exchange and government resources, (KS Jomo, 2024).

III] DIGITALISED LABOUR

Nested in the platform capitalism model is the software component and the associated IT infrastructural platforms’ solutions. Unlike in the manufacturing sector where labour is kept within borders while capital moves freely, in Big Tech there is this process ability to intrude into a target country to install infrastructural platforms as well as troll the planet for cheap labour in any part of mother Earth at any time.

The resultant, and a transformed economy, is the gig economy, also widely defined as “platform economy”, “on-demand economy” or “sharing economy”, synchronises to the demand and supply of short-term or task-based work activities, and as a part of the national economy where freelancing workers use digital platforms to participate in the national economy, including their connections with the traditional yet formal businesses. According to Emir Research, about four million people in the Malaysian workforce which is about 26% of the labour force work in the gig economy; this is almost double the global average.

This business model is what technology guru Azeem Azhar names as the ‘AI lock in loop’ where, as the tech companies deploy products and services, they also collect data about their consumers’ use of those products and services. Through machine-learning processes performed on those collated data, these business entities envisage in presenting opportunities towards the development of better products and services. It is by integration of multiple data-rich digital assets into a single platform that gives such tech companies access to the entire vertical product chains (examples like Google or Grab siphoning off personal biodata and geographical locations) and the supply-chain capacity to expand horizontally into new products and services with relative ease and effectiveness. For examples: Google, Facebook, WeChat or Grab becoming cloud-servers, WhatsApp as a communications medium and Instagram an media aggregator, (Social Europe, Gig Workers Guinea Pigs of the New World of Work, February, 2021 where ‘bogus’ self-employment workers are left outside of the regulatory framework; Foundation for European Progressive Studies, Governing Online Gatekeepers: Taking Power Seriously, 2021; see also ILO 2021 report on the states of precarious digital labour.

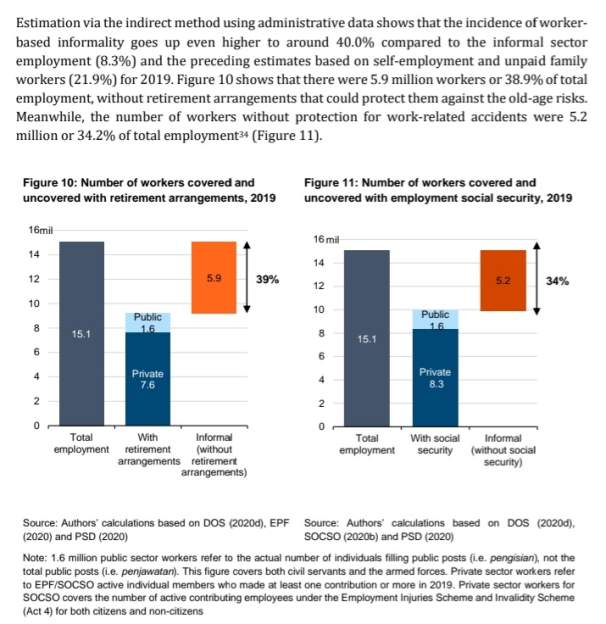

In case country Malaysia, the adoption of digitalisation only deepen the stronghold of the monopoly-capitalised infrastructural platforms that support artificial intelligence domain, in the digital frontier and defranchised digitilased zero-hour gig-labour, (STORM 2023). This informal employment sector not only occupies a sizeable segment of the country’s workforce but inevitably it is without adequate social security safety provisions in place, (read csloh, 2022: Workers; Emir Research: Brain Drain; bernama: gig-economy and Khazanah Research Institute 2020, Shrinking “Salariat” and Growing “Precariat”?):

For AI to bind adhesively within a national economic development initiative, not only must the monopoly-capital-compradore-capital eIements be done away, but the labour exploitation factor be eliminated, too. Labour superexploitation conceptually captures the real condition of the working class in Africa, Asia and south America. It involves three elements: low wages, long hours, and intense work leading to due strenuous exhaustion. Above all, it is characterised by “the greater exploitation of the worker’s physical strength, as opposed to the exploitation resulting from increasing his productivity, and tends normally to be expressed in the fact that labor power is remunerated below its real value.” Ruy Mauro Marini.

An AI class analysis can be by way of applying Nicos Poulantzas concept of class [places] as existing at each of levels of society: economic, political, and technological.

The class [positions] of the capitalist fundamental class processes are productive endusers (performers of data entry) and productive capitalists (extractors of processed data in the form of information).

The class relationship where dominating [power] ensues would be identified, therefore, through the stronghold of infrastructural platform [place] which has allied with financialised capital providers [positions] in the provision, control and ownership of software, hardware and process [power].

Capitalists appropriate surplus value from the consumption of enduser’s labour activities during the generation of data into processed information. The surplus (monetary and or metadata of say geographical locations in an e-hailing process) is distributed as extracted among beneficiaries of subsumed class positions like the state-enabler, IT vendors, financiers and compradore monopolies.

In essence, historical politico-economic development of a country comes from social practice, the struggle for production, the class struggle, and scientific work.

For the SCRIPT in Madani Malaysia to be successful, in term of implementation and sustainability of an AI-driven progressive politico-economic developmental praxis, working-class unity has to be consolidated. It can only be further solidified if the tenet of divisive divisions by capitalism is better understood both in theory and in practice. Hence, we argue for a comprehensive yet bold project that is based on TAPAO that goes beyond its ethos as a renewal of an socialist ideal with Malaysian characteristics in order to take full account of the struggle of the labour movement.

EPILOGUE

What are the remedies to limit infrastructural platform capitalism dominance, the AI perversion and the digitalised colonisation process?

A global tax on capital or the implementation of the Wealth Tax at the national level, is one way to allow for the creation of a “social state” meeting social needs, (Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century).

Taggling digital labour by putting the most essential needs of people and the environment before profits where provision “jobs…for the unemployed, food for the hungry, houses for homeless, adequate health care and income security and a decent environment for all of us” whereby the highest priority is an implementation of these collective human goals to which all special interests would then be subordinated. (Magdoff and Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion, 88–90).

Towards furtherance in engaging union activity and an unity to fight for a higher share of income to build transnational solidarity allies with the national considerations in outreaching, mobilising and organising mass of gig- workers in the country; see the manifesto proposal in Towards a post-2020 political economy and in an edition of the journal newleftmalaysia, Renewal of a Socialist Ideal, and TAPAO towards a truly national economic development initiative on the sharing of common wealth.

RELATED READINGS