8/05/2024

I PRESENT OUTLOOK

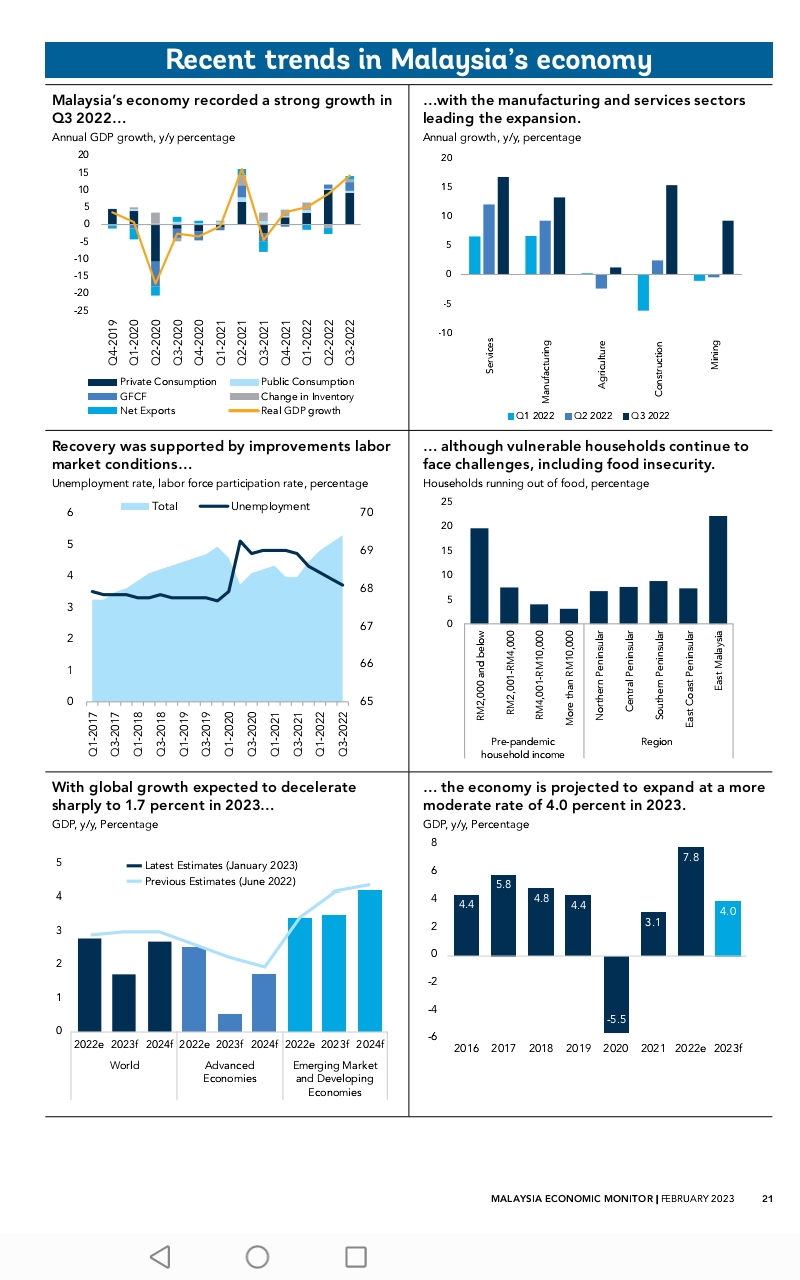

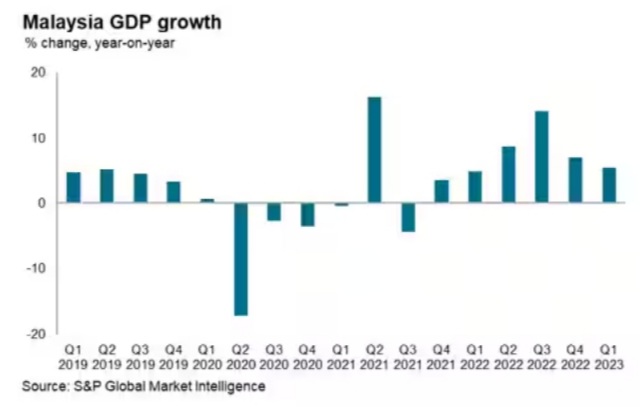

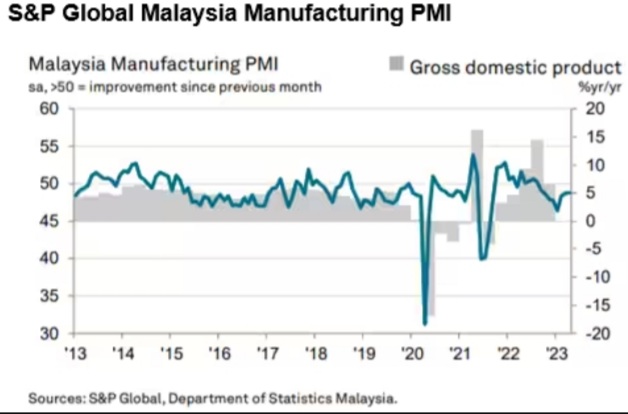

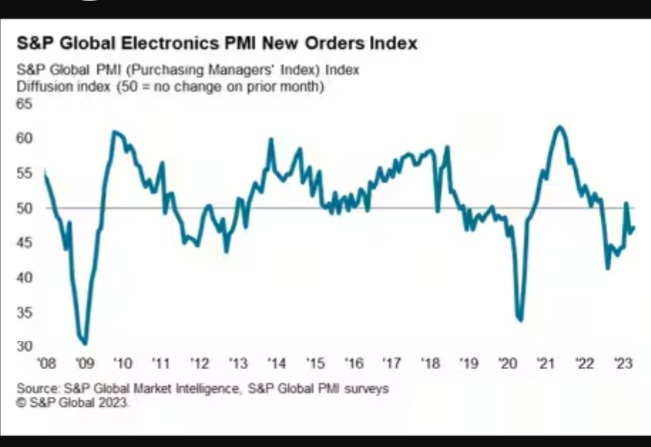

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has revised the outlook for Malaysia’s real gross domestic product (GDP) by a notch to 4.4 per cent this year from its earlier prediction of 4.3 per cent, (IMF 17 Apr 2024), whilst Bank Negara Malaysia projects 4%-5% GDP growth in 2024 when global growth is expected to rebound in 2024, driven by the technology upcycle, tourism recovery, and low base effects in 2023, (Bank Negara in its annual report released on 20 Mar 2024), primarily underpinned by continued expansion in domestic demand and improvement in external demand.

The IMF growth estimation for the country is based on its World Economic Outlook, April 2024 which is to be Steady but Slow: Resilience amid Divergence. That the baseline forecast for the world economy is to continue growing at 3.2 percent during 2024 and 2025, at the same pace as in 2023. Also, it is based on an expect real (inflation-adjusted) U.S. economic growth of about 2% in 2024, higher than its initial estimate of about 0.5%.

II YEAR 2022 GLOBAL

The present year has a better forecast than whilst in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic year of 2022 when there were many encountered economic turbulences.

The first headwind is a global financial tightening. The Federal Reserve was then much more aggressive in tightening monetary policy as U.S. inflation remained stubbornly high. This was translated to tighter financial conditions for Asia. Sovereign yields had also risen, and capital outflows in emerging market Asia leaked as voluminous as in past stress episodes, even though they remained limited to a few economies.

The second headwind was the continuing conflict in Ukraine, which inevitably led to a spike in commodity prices. Most countries in Asia had also seen a deterioration of their terms of trade. This situation was an important factor behind currency depreciations insofar as in 2022.

The third headwind was the sharp and uncharacteristic slowdown in China. The IMF have had thus marked down Chinese growth for 2020 with 3.2%, its second lowest level since 1977. This reflected the impact of the zero COVID lockdowns on mobility and the crisis in China’s real estate sector. The slowdown was then estimated to have important spillover to the rest of Asia through trade and financial links. Zee

During the 2022, the headwinds were contributing to a global slowdown compared to the April World Economic Outlook. As such the IMF has had downgraded its forecast for growth in Asia and the Pacific by 0.9 percentage points in 2022 and 0.8 percentage points in 2023. So, the growth was at 4% in 2022 and 4.3% in 2023 while inflation grew more modestly in Asia in 2021. This change follows the sharp volatility in global commodities since the war in Ukraine. This increase reflected both rising food prices, particularly in Asian emerging market and developing economies, but also higher core inflation as region recovered and output gaps had loss. Indeed, core inflation had once again exceeded central bank target in most Asian economies and in most cases by a wide margin. It was argued that there should be a need for further tightening of monetary policy to ensure that inflation returns to target, and inflation expectations would then remain well anchored.

At that time, it was expected that fiscal policy would have to complement monetary policy to fight inflation around the world in Asia. Fiscal consolidation was also advised to be incorporated to stabilize public debt. Asia is now the largest area in the world and so comes at high risk of debt. It was further felt that distress positions and rising interest rates could possibly pose financial volatilities from high leverage and unhedged balance sheets and further risks increases in public debt ratios.

The challenging conjuncture then was aggravating the medium-term economic scars opened by the pandemic, which was expected to be aggravating worsen in Asian. Also, it was assessed that much of the shortfall in growth in Asia relative to other regions could be further explained by lower levels of investment, employment and productivity following the pandemic. While exact policy responses at that 2022 period would expected to depend on country specific circumstances, tackling corporate debt overhang and mitigating human capital losses would also be important for a wide range of countries in the region.

During this period, the prospect of greater geo-economic fragmentation was also a significant risk to the region. In the report, it was stated that worrying early signs of fragmentation and consequences of a destruction of global trade links. One such sign of fragmentation pressures emerged from the crises was elements of trade policy uncertainty. In fact, the spiked in 2018 amid tensions between the United States and China and had further accentuated amid Russia’s trans-border war in Ukraine as sanctions created uncertainty around future trade relations. The IMF analysis at that time had indicated that a typical shock to trade policy uncertainty like the 2018 build up of China-U.S. tensions somewhat reduced investment in the region by about 3.5% after two years. It had also projected a decreased gross domestic product by 0.4% and raised the unemployment rate by 1 percentage point.

In addition to rising uncertainty, the prevalence of harmful trade restrictions was stated to have increased since 2019. The sectoral decomposition of trade restrictions had also been shifting. The shared restrictions that target high tech sectors had also been steadily increasing since the global financial crisis. Since the war in Ukraine, restrictions targeting the energy sector had also increased sharply, while those aimed at high tech sectors had also remained high. During that period, the IMF team had considered the long-term risks of deeper fragmentation scenario, and as such have had articulated the consequences of a purely hypothetical global economy divided along the lines implied by the votes cast on March 2nd, 2022 United Nations General Assembly motion to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It was evisaged then if the world would to be demarcated into two separate blocs, then the losses could become significant. Global losses were then expected to be of 1.5% of GDP. Whereas, those in Asia were slightly over 3%, with losses forseen to be especially large for countries with a high level of openness and that have production structures that straddle both blocs.

III 2025 FUTURE

The IMF has earlier raised this year’s gross domestic product growth outlook for the region to 4.5% from the previous 4.2% estimated in October, with China’s figure upgraded by 0.4 percentage point to 4.6%.In the latest regional outlook released, the IMF pointed out that fiscal stimulus enacted over the past several months helped buoy the economy. It added that its China growth forecast for 2024 “may be revised upward,” as the country’s first-quarter growth came in stronger than expected. But it warned of several challenges for Asia’s largest economy. “Chief among risks for Asia’s economy remains a protracted property sector correction in China,” it said in the report, expressing concern that this may weaken demand and make continued deflation more likely. In addition, the IMF raised the issue of industrial overcapacity weighing on industries from steel to automobiles recently. “Policies that boost supply, such as investment subsidies to specific companies and industries, would worsen overcapacity, reinforce deflationary pressures, and potentially provoke trade frictions,” the IMF said. China’s official purchasing managers’ index released had shown the country’s manufacturing activity grew for the second consecutive month in April.

As for Malaysia’s outlook, in its latest World Economic Outlook (WEO) entitled Steady but slow, resilience amid divergence, IMF predicted the GDP growth to remain at 4.4 per cent in 2025. It projected Malaysia’s current account balance at 2.4 per cent in 2024 and 2.7 per cent in 2025.

By ensuring such growth prospects

Characteristic Gross domestic product:

2025: US$477.83 B

2024: US$445.52 B

2023: US$415.57 B

2022: US$407.03 B

would be determined by the GDP growth in the United States which is projected to be 2.6% in 2024, before slowing to 1.8% in 2025 as the economy adapts to high borrowing costs and moderating domestic demand. According to Wang and Tyler, the economic data should “give more confidence that the US economy is recovering in additional sectors” and that “recession fears for 2024 are likely to be pushed into 2025.” On the other hand, GDP in China is expected to reach 18825.00 USD Billion by the end of 2024, according to Trading Economics ( TE) global macro models and analysts expectations. In the long-term, the China GDP is projected to trend around 19673.00 USD Billion in 2025 and 20617.00 USD Billion in 2026, according to TE econometric models.

On Malaysia, the stock market rallies in early May 2024 has given a momentum to the country’s economic wellbeing.

Malaysia’s FBM KLCI climbed to a two-year high on 7th May 2024 as gains of consumer and banking stocks extended the benchmark index’ rally to its fourth straight day.

The KLCI rose as much as 12.93 points or 0.8% to 1,610.32, its highest since May 5, 2022. The index closed at 1,605.68, still up 8.29 points or 0.52%, with 24 out of 30 constituents posting gains.

These gains also propelled Malaysian stocks’ market capitalisation to RM2 trillion in for the first time ever. The gains appear sustainable and on track to hit 1,755 by the end of this year, CGS International has stated. The aggregated 12-month target for the KLCI stands at 1,683 points where Bloomberg data have indicated.

By paying more attention to domestic-driven sectors, it is expected that the domestic economy will be picking up with an improved growth regime in both private consumption, and more importantly better gross fixed capital formation in the country’s economy.

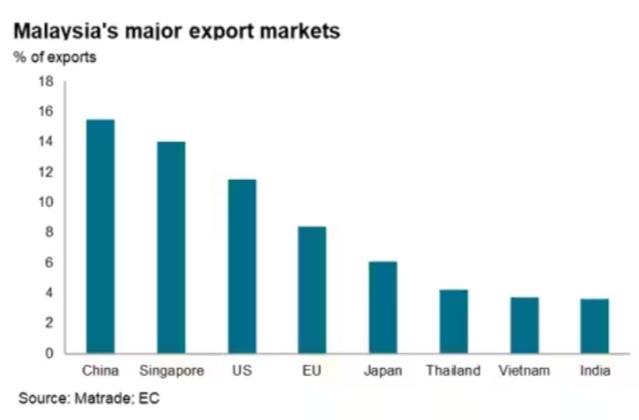

Further, on the the 50th anniversary of diplomatic ties and foster deeper economic collaboration between Malaysia and China, it is envisaged that with the Malaysia’s Madani initiative, launched in January 2023, aligning with the values and principles of the Community Shared Future (CSF) advocated by President Xi Jinping since 2013, Malaysia foresees significant potential for deepened collaboration with China, notably in infrastructure, the digital economy, green development, new energy vehicles, and the rare earth industry – whereby and thereby, the Malaysia Madani economic framework will be able to strengthen her national competitiveness by focusing on fiscal sustainability, excellent governance, and effective service delivery thenceon by 2025.

Related References

STORM August 2023, structuring the Madani model

Malaysianewleft, February 2024, geoeconomic challenges for the Madani model

Firestorms, May 2022, geopolitics in a multipolar world

csloh.substack, June 2022, IMF’s Malaysia

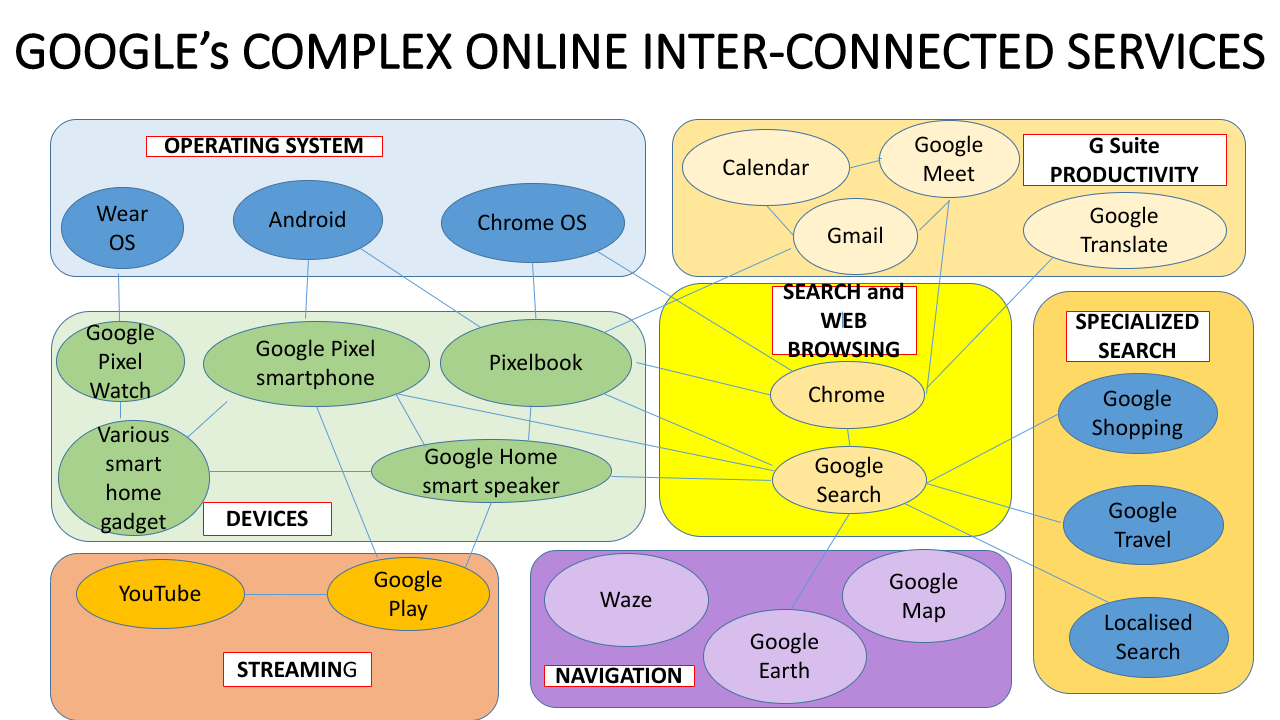

Tech companies are the new empires of today: Alphabet revenue surpassed Hungary’s GDP, Facebook employs over 15000 content moderators around the world, and Microsoft has built data centers in nearly every corner of our planet, with Google global dominating the infrastructural platform corporate businesses.

Tech companies are the new empires of today: Alphabet revenue surpassed Hungary’s GDP, Facebook employs over 15000 content moderators around the world, and Microsoft has built data centers in nearly every corner of our planet, with Google global dominating the infrastructural platform corporate businesses.