08/08/2023

1] INTRODUCTION

In the narrative of MADANI concept and on the conversations following such a propogation, it was pointed out that two critical components in the approach on national economic development may restrict, and even retard, the pulsating economic push forward.

There has to be a dual-prong approach to ensure the maintainability and viability of the MADANI model trust and performance thrust. The primary retrograding elements that are limiting the forward push boldly lay in the availability of sizeable financial resources in activating economic development projects and programmes, and the other is an inertia of the public service sector in assisting the implementation process effectively by its own deficient yet administrative weaknesses.

2] DEVELOPMENT REVENUE SOURCES

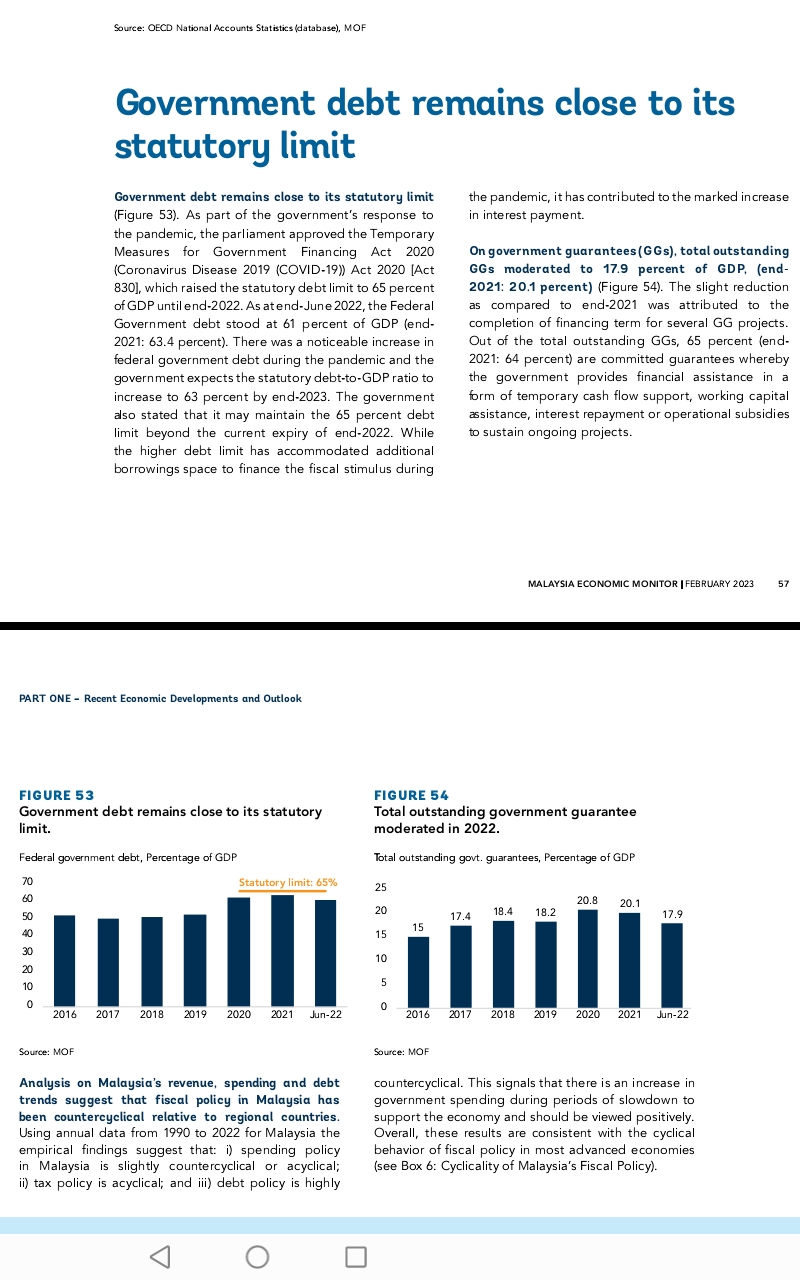

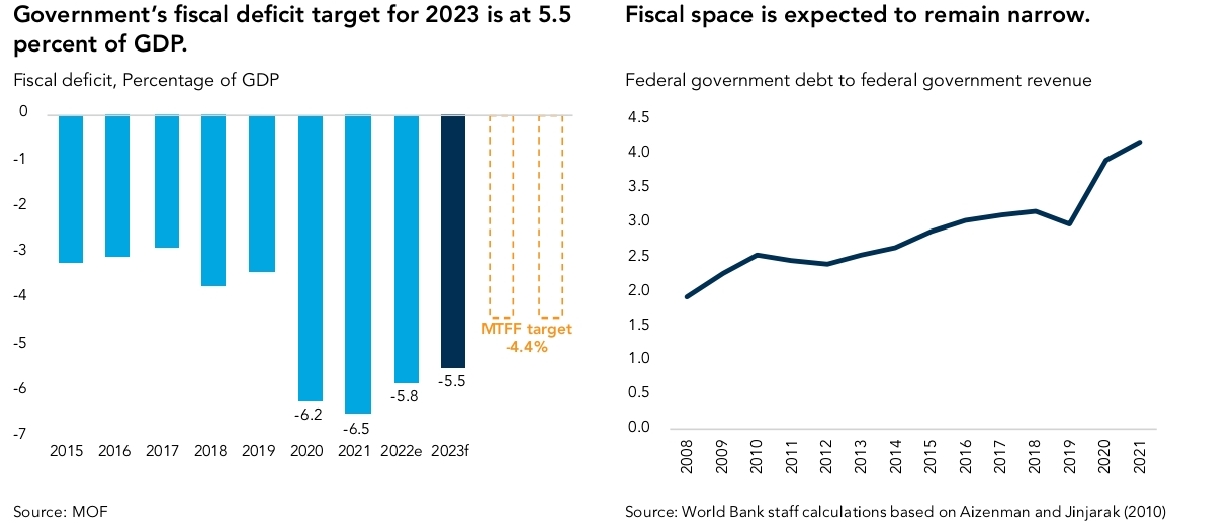

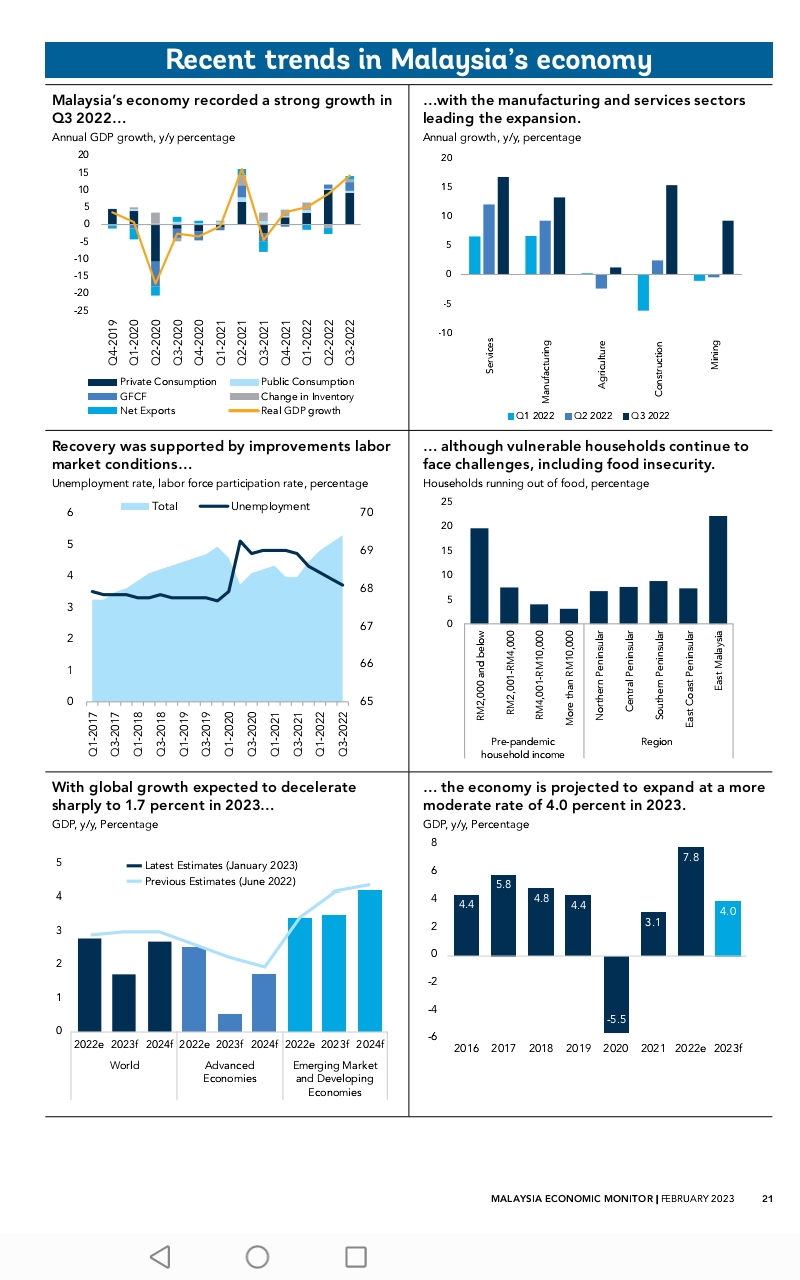

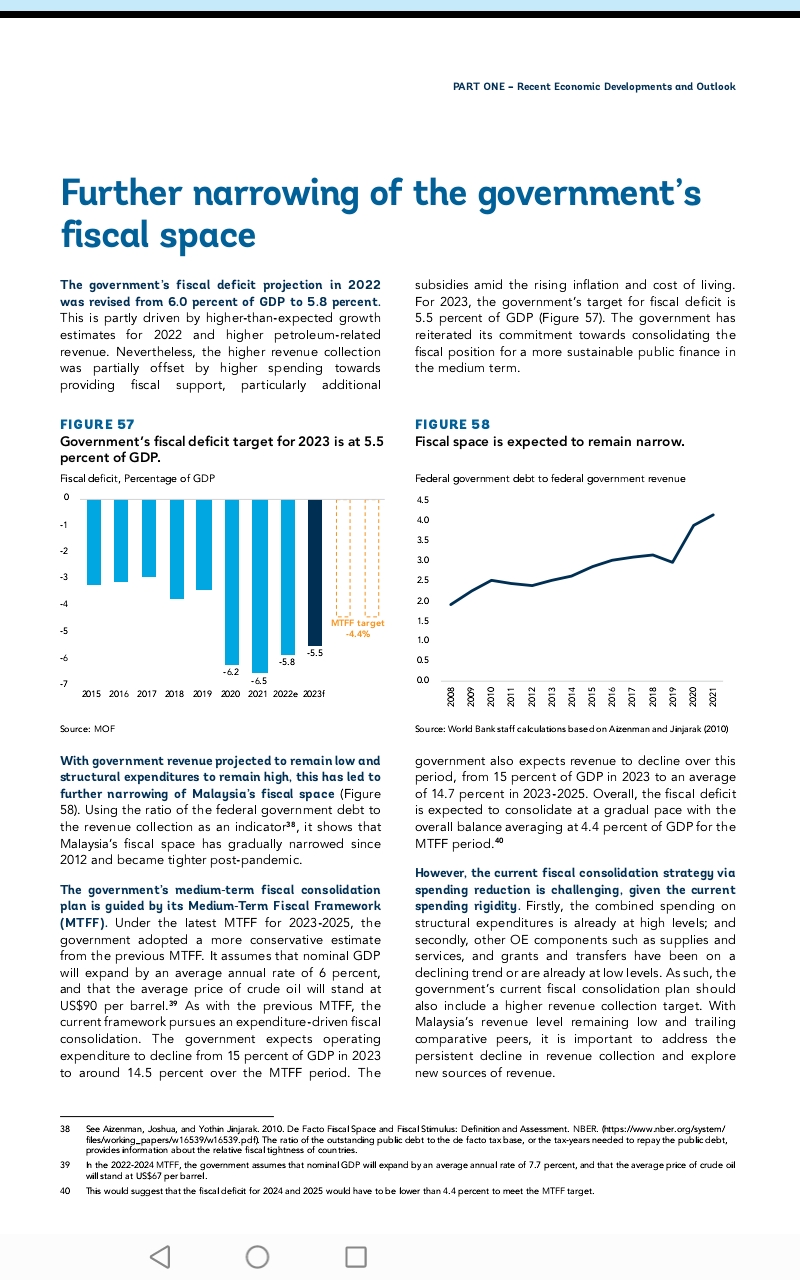

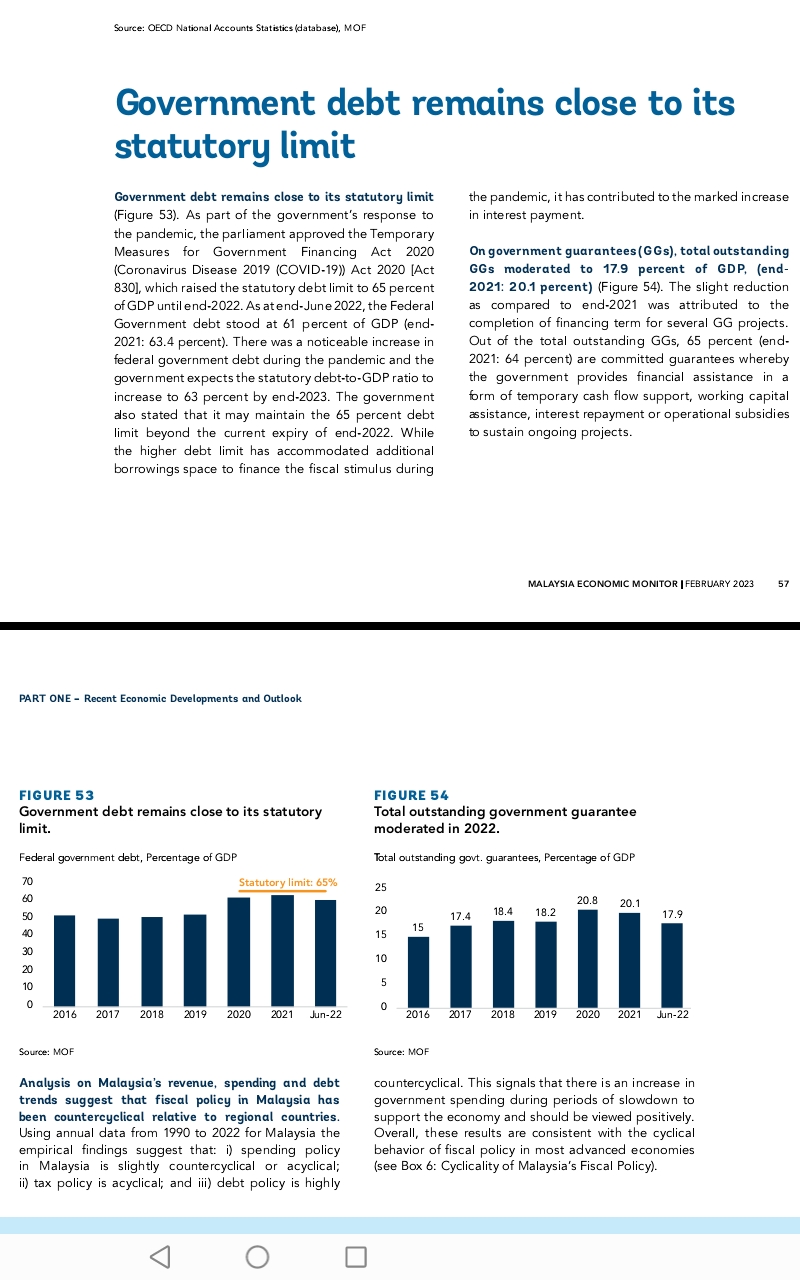

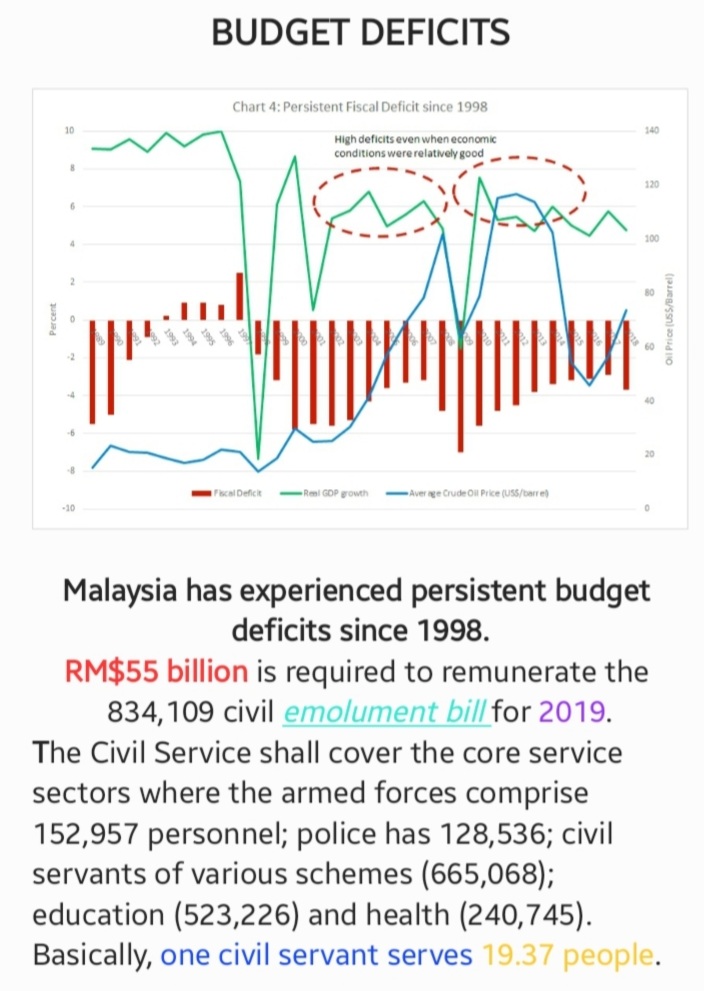

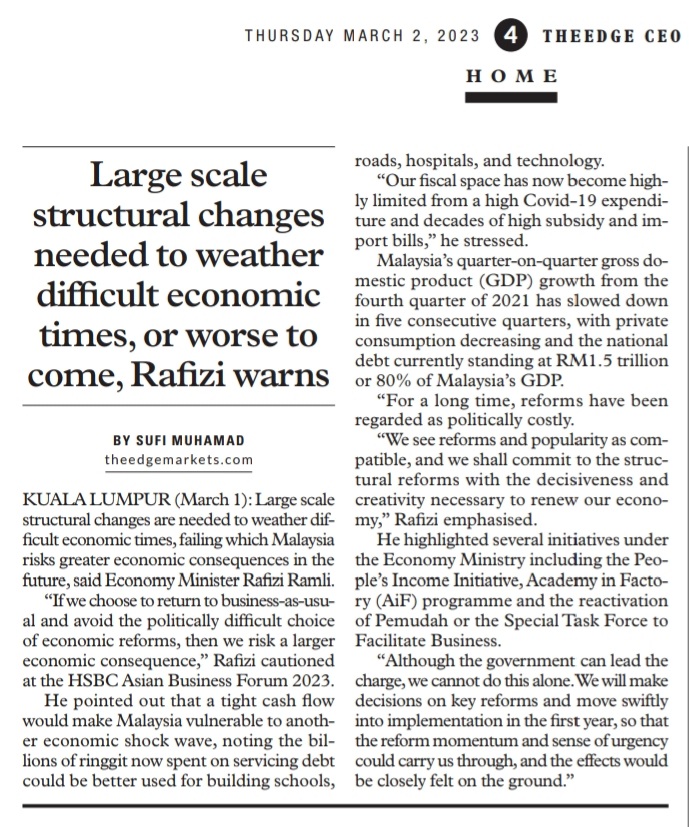

At present, the World Bank has indicated that Malaysia’s fiscal space has narrowed considerably since 2012 and has in fact became even tighter post-pandemic. Indeed, the current fiscal consolidation strategy – via spending reduction – is, to many national economists and political analysts, (bfm.my, IDEAS, theedgemarkets, O2 Survey) rather challenging, given the current tight spending domain.

The way out:

A) Sovereigns can borrow from within their own country or from abroad.

Domestic borrowing – from local banks and asset managers or directly from households (EPF employees’ money or PNB owners’ saved trust units) could likely be a steady and reliable source of financing. However, there is a limited amount of money available and repayment maturities tend to be short.

Not infrequently, governments also borrow from international capital markets, in larger amounts and usually at longer maturities.

Otherwise, there is a wide and diverse range of private sector entities willing to lend to sovereigns, too. Asset managers, such as pension funds, typically hold a large amount of government debt. They need relatively safe long-term assets to match their long-term liabilities.

B) In big ticket projects, such infrastructure constructions like highway extensions or light transit transit system can be financed typically through government budgets, either from tax revenue or from government borrowings, and in past projects some had often been financed through special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) — for example, DanaInfra, which was set up to raise financing for several infrastructure projects. The debts of these SPVs are guaranteed by the government, and hence, can be considered ultimately as government debt.

Many public infrastructure projects have also been privatised, and the private investors would recover their cost of investment through collecting tolls or charges from the users. Examples of these include the toll roads, independent power producers and land-swap projects. In such cases, the government does not carry any liability for these projects unless it has given some form of revenue guarantees to these private investors. This financing model (using private-sector finance and project development expertise) is known as a public private partnership (PPP).

Not often publicised is another variant of PPP, where private investors recover their cost of investment through payments from the government. This is generally known as a private finance initiative (PFI) which has its many odious transactions. PFI payment obligations comprise a large proportion of the PPP debt of RM$201.4 billion, which was only known, and later announced, by the preceeding government in May, 2022, (read PFI, 2022).

Inevitably, instead of borrowings that incurred interests, a progressive way is to implement a windfall tax on industries that benefit greatly, according to Khazanah Research Institute senior advisor Professor Dr Jomo Kwame Sundaram.

“This is precisely the time when you must reform taxes as you have it (windfall tax) all the time amid extraordinarily high petroleum prices or palm oil prices.”

This view is also concurred by the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies research fellow, Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid, who pointed out that policy-makers tend to ignore the imposition of capital gains tax when it comes to the issue of tax reform.

Even Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) assistant governor Dr Norhana Endut noted that the government’s tax collection capacity had not kept pace with the economic growth.

Indeed, Malaysia tax to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio, has been on a steady decline over the medium term. It fell to 12% in 2019 from 15.6% in 2012.

Further, Malaysia’s individual income tax also continued to come from a narrow pool of taxpayers. For instance, in 2018, among a labour force of 15 million people, only 2.5 million were taxpayers!

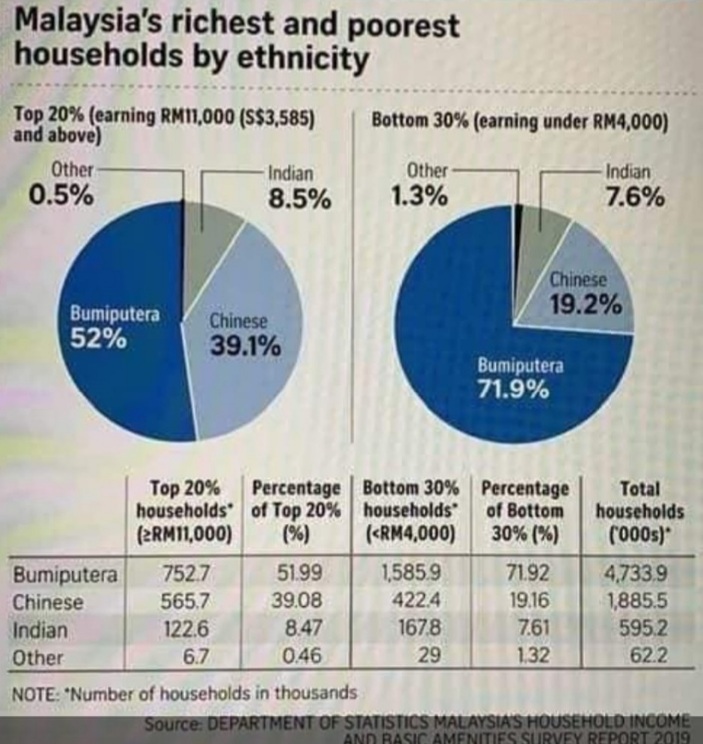

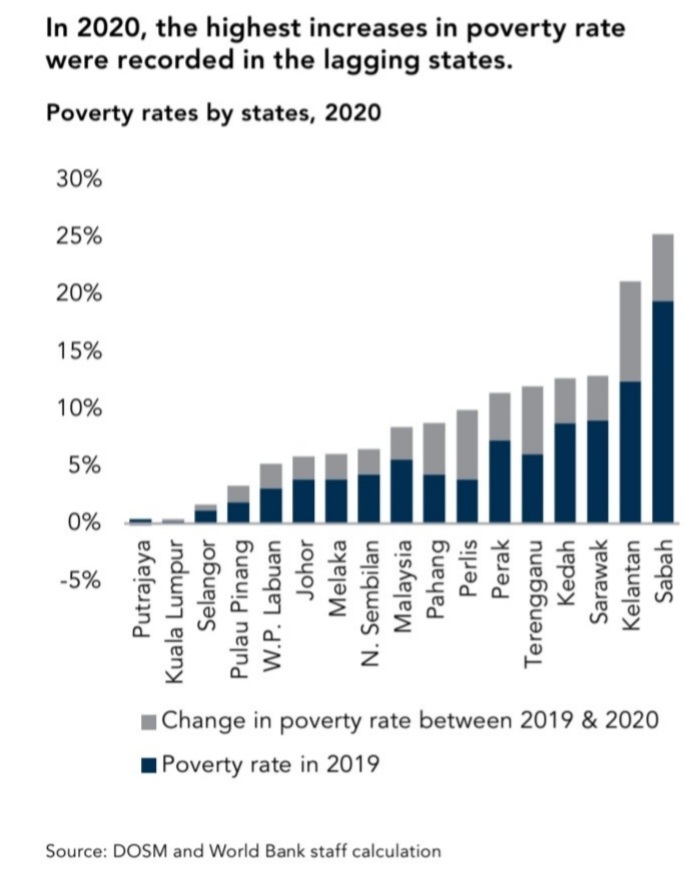

There is a definite need in expanding the tax base be a priority over the medium term, besides existing tax incentives and exemptions should be reviewed on a regular basis as some of them are outdated and ineffective, affecting the beneficial economic development among the marginalized poor’s.

This is also during an era of inflationary trend. Global inflation is expected to fall to 6.6 percent in 2023 and 4.3 percent in 2024, still above pre-pandemic levels, thus socio-economic impacting heavily on the B40 rakyat².

“Malaysia, of course, benefits from having oil and gas revenues as a source of non-tax revenue, but these have tended to be quite volatile,” so said Richard Record, one-time the World Bank Group’s lead economist for Malaysia. The country definitely needs to raise more revenue and spend it more effectively.

Present revenue collection is low mostly because rates are low and there are so many allowances and exemptions benifitting capital. Reforming the SST (Sales and Services Tax), and in particular sharply reducing the number of non-essential items that are zero-rated or exempted from.

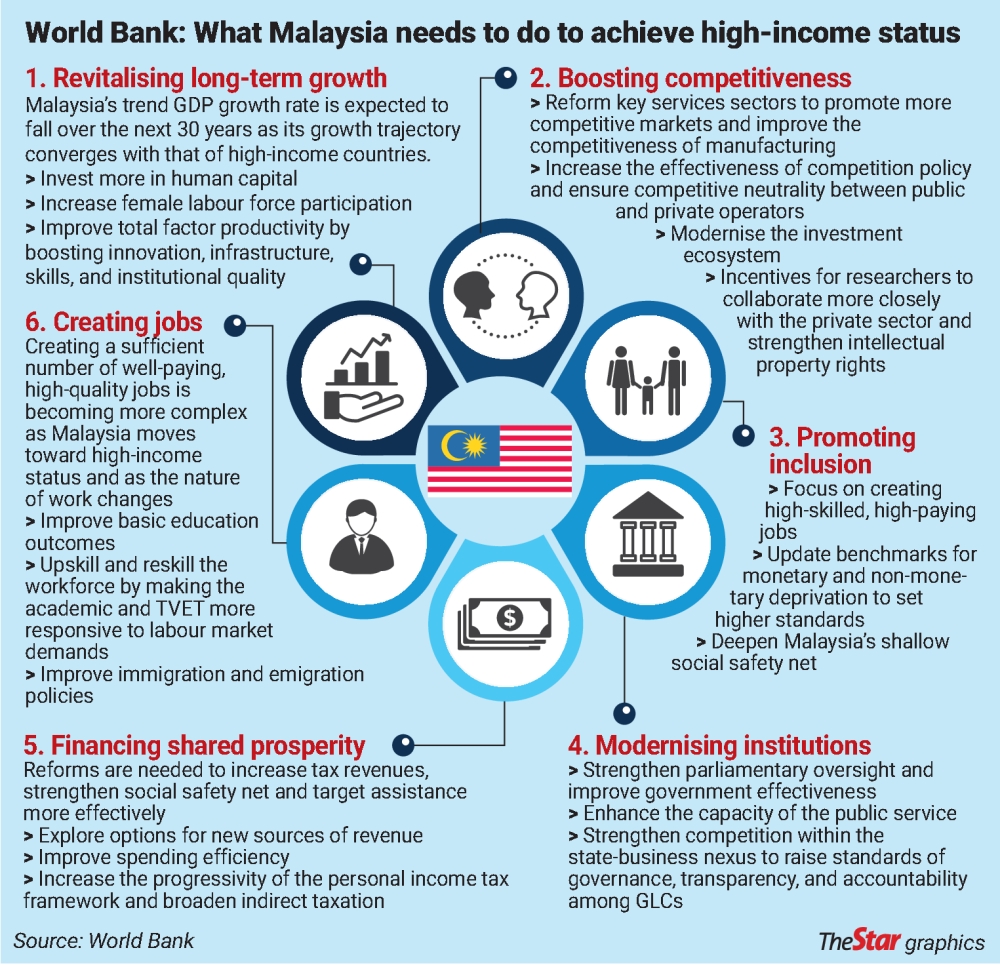

Indeed, there should be greater effort across tax instruments: to increase the progressivity of personal income tax, re-examine the number and targeting of corporate income tax incentives and to consider new sources of revenue such as environmental taxation and capital gains taxation, and even a wealth tax.

The introduction of capital gains tax, raising the tax rate for those in the top individual tax bracket and imposing a tax on retirement savings above a certain threshold were among the suggestions on how to enhance revenue in the World Bank Report, 2021.

If the present Government continues to borrowing – the interest rate has to be minimal – then it has to prevent the structure of such debts from becoming too risky. This is because, at one time, we find it cheaper to borrow in US dollars or euros than in our own currency. However, this finanancial method can cause problems if the ringgit depreciates because this increases the real burden of the debt – as was clearly exemplified proportionately in the 1MDB case, and at times of a present ringgit depreciation.

D) Otherwise, it is to apply traditional methods like using Government bonds issued to finance budget deficits but with a glaring pitfall. If there is a continuous growth of debt, the private sector creditors may become concerned about the government’s initiative to repay it. Over time, these creditors will expect higher interest payments to provide a greater return for their increased perceived risk as it is widely acknowledged that higher interest costs dampen economic growth.

On the other hand, for Danaharta it uses cash to purchase loans from the domestic banking system by paying sharp discounts of as much as 50 per cent on a loan that was either collateralised by property or shares listed on the stock exchange.The consequence is too much liquidity in the matket, and the country went south can be partly identified to the solidification of financialisation capitalism (see: Southampton’s Lena Rethel Financialisation and the Malaysian Political Economy).

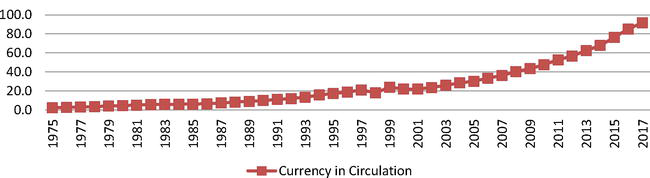

The flooding of money in the market is not to generate wealth but within the circuit of financialization capitalism components of FIREs (finance, interests, real estate) in furtherance of repaying mortgage loans, hire purchases, insurances, real estates tax dues and other debt interests.(Rajah Rasiah, 2011) has ambly demonstrated that with accentuated and expanded monetary instruments circulation, the national economy had impaired, through wide currency circulation, unfavourably:

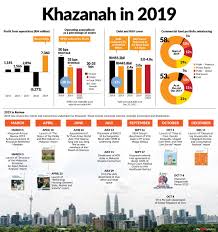

E) Inheriting such a burgeoning debt burden, sovereign wealth fund Khazanah Nasional Bhd could sell its assets to raise cash for the state of a nation as she is sitting on assets easily worth more than US$30.5 billion (December 2021) that could probably raise over 10% of the government’s +RM$1.5 trillion debt and contingent liabilities.

Another financial resource lies with Petronas as it is financially in a comfortable position to pay, given that its total assets has strengthened during 2022.

On March 14, Bernama reported that Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) posted its strongest financial performance with a net profit of RM101.6 billion in the financial year ended Dec 31, 2022 (FY2022), up 100 per cent against RM50.14 Mar 2023.

• Strengthen the oil and gas (O&G) sector by enhancing the attractiveness of existing energy and petrochemical hubs, increasing and intensifying exploration in the South China Sea and offshore deepwater elsewhere in the world. The objective is to maximise output and to include a robust stockpiling policy and infrastructure for rainy days.

Malaysia’s petroleum reserves for oil and gas resources are projected to last for only 15 years, according to the Reserves Life Index calculation. However, this may be stretched to over 40 years through high capital investment, new technologies, as well as a more stable and competitive investment landscape, according to Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department Datuk Seri Azalina Othman.

• Diversify and expand the O&G sector by transforming Petronas and its subsidiaries from an O&G or oil and energy company into a global industrial conglomerate, not limited to expansion and investments into energy and renewable energy business and assets, but into renewable chemicals, petrochemicals, materials and other businesses. The term “core” business must be wider and more flexible to quickly adapt to market forces and disruptions.

F) Alternatively, government-linked companies (GLCs) and government-linked investment corporations (GLICs) would also likely be encouraged to pay higher dividends. The government could tap these state enterprises to help out just as like the recent RM$58 billion stimulus package to counter impact of the Covid-19 pandemic 2020 crisis.

G) Another definitive prospect is to spur local start-ups, government-linked companies including Khazanah Nasional Bhd and EPF in investing RM$1.5 billion for those that are innovative and have high-growth potential. This model will see a lead company (not as yet identifiable, but capital shall continue to dominate as Jomo observed in a French Embassy-sponsored forum) that shall partially or fully take over the operation of TVET institutions and revamp training programmes so that they meet industry needs: provisio it is free from identity politics but based on Madani politico-economics mantras.

Inheriting such a burgeoning debt burden, sovereign wealth fund Khazanah Nasional Bhd could sell its assets to raise cash for the state of a nation as she is sitting on assets easily worth more than US$30.5 billion (December 2021) that could probably raise over 10% of the government’s +RM$1.5 trillion debt and contingent liabilities.

H) An excellent yet viable alternative foundation is the formation of a new sovereign fund to be created with Khazanah and Petronas seedings.

There are many units in Petronas that can be unlocked, restructured and new entities created to maximise the high productivity in an energy-rich supra-system. Through transformation processes or facilities, leading to improved efficiency in energy use and yield, and generating clear financial benefits, too

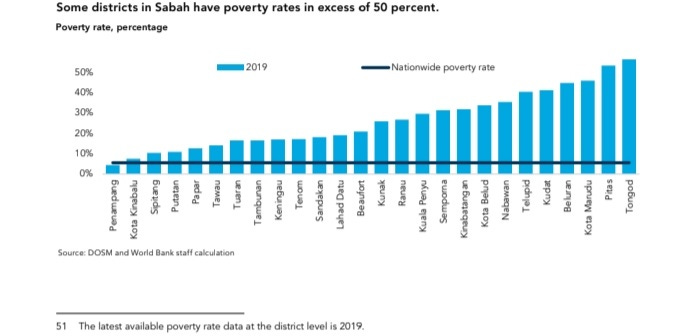

Many of the multiple approaches stated above need to be implemented because of the narrowing of Malaysia’s fiscal space (see right chart below): Using the ratio of the Federal Government Debt to the revenue collection as a reference point, the World Bank has indicated that Malaysia’s fiscal space has gradually narrowed since 2012, and had became even tighter post-pandemic if due developmental processes are not undertaken, (read STORM 2023, Debt financing towards progressive growth path).

Using the ratio of the Federal Government Debt to the revenue collection as a reference point, the World Bank has indicated that Malaysia’s fiscal space has gradually narrowed since 2012, and had became even tighter post-pandemic if due developmental processes are not undertaken, (read STORM 2023, Debt financing towards progressive growth path).

3] PUBLIC SECTOR INERTIA

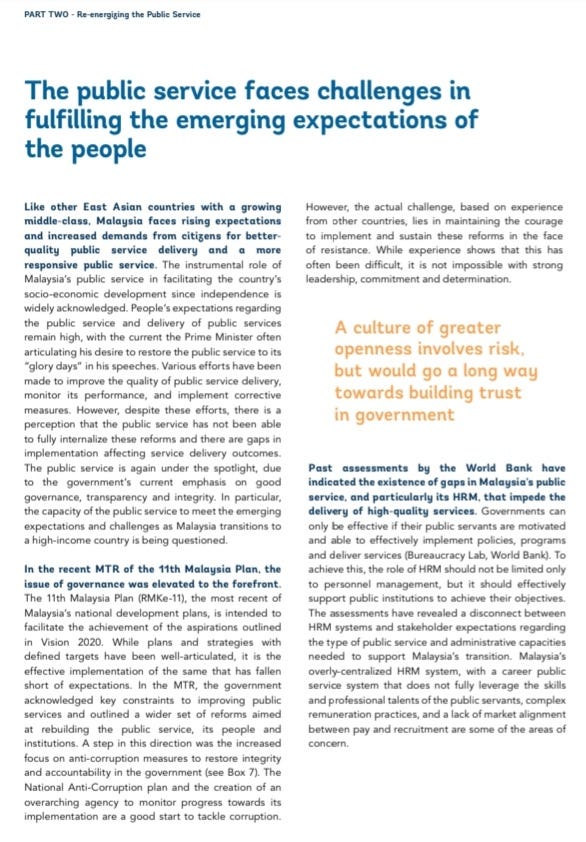

The second critical prong requires structural reorganisation of processes, procedures and people elements and parameters in the public service sector that has had its critical deficiencies in efficiencies and effectiveness on the delivery of socio-economic services and implementation of physical projects.

The Malaysian civil service is a patriarchal and rigid hierarchical organization, where privileged placing, positional status and accrued power are much more valued than creativity, and effective productivity whence it is considered threatening to outshine a superior at the rank of director and above. Indeed, the power-distance relationship in Malaysia is the highest in the world, (Hunter, 10/022023).

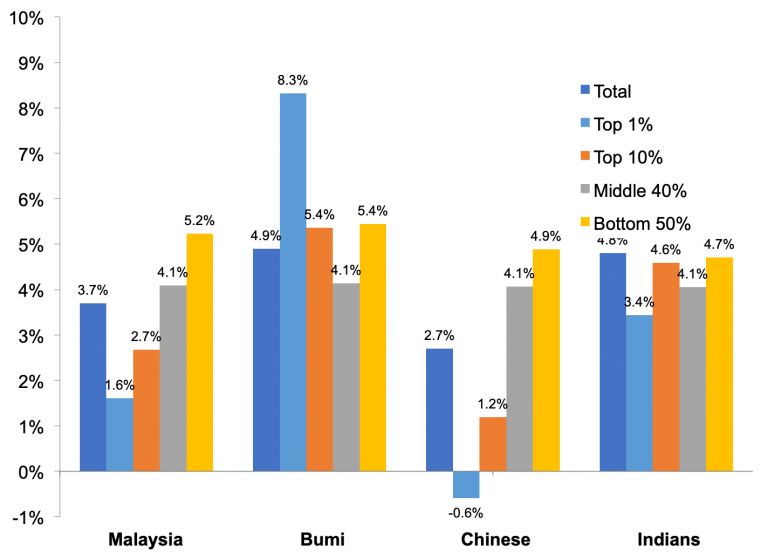

Nicos Poulantzas conceives a neo-Marxian concept of class and class processes when “places” are distinguished from class positions where “places” exist at each of the these levels of an organisational society: economic, political, and cultural levels where at the latter, social dominance regards a bumiputeras status as the premier preference.

A) A multi-dimensional approach is a possible way to improve public service performance besides understanding – and improving – upon public-sector productivity in the country.

A methodology may assume tasks such as these:

i) gather expenditure data as a starting point in examining budget execution rates, providing a baseline assessment on productivity variations focused on programs and activities undertaken by the Ministeries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs).

ii) then, by combining this information with other data such as project completion rates and administrative data from the MDAs, possibly allowing for a more granular look into productivity variances and how drivers such as ICT and digital technology, administrative capacity, training and development, financial and non-financial incentives can influence productivity levels

iii) then, there is a wealth of administrative data on the public sector, such as on budget-execution and project-completion, that can be used to undertake a deep-dive diagnostic assessment into how productivity varies across public spheres and organizations and what might be the drivers of their activities.

iv) Then, rather than mere ministry-centric, a strategic economic development initiative should embrace the quintuple helix approach where The State mobilises five subsystems (helices), comprising:

(1) education system,

(2) economic system,

(3) natural environment,

(4) civil society, and

(5) the political system

to formulate a critical vision in not only articulating the objectives in the inter-linkages on conceptual visionalisation, but also the design and development of such vital mission objectives to implement: maintainable – yet sustainability in the long economic development haul ahead.

Hopefully, with such diagnostic assessments they shall assist in strengthening the conceptual framework around public sector productivity in Malaysia, identify areas around which future analyses and impact evaluations should focus, and highlight areas where measurement can be improved.

B) Can productivity performance objectives be executable or even achievable?

Here are some selective country case-studies and their resultant outcomes that can be learnt from:

i. Improving administrative human-resource capacity, by ensuring that public administrations are well staffed and have the competencies and resources to meet task demands. Basri et al (2021), for example, found that tax organizations in Indonesia that invested in improving their administration capacity (at a cost of 1 per cent of revenues) saw a 128 per cent increase in revenue collected.

ii. Merit-based recruitment can ensure that public administrations are staffed with well-qualified and competent staff that are able to effectively complete their tasks, perform at a high standard and generate new innovations and ideas. Evidence from the Brazilian civil service demonstrates the effectiveness of competitive examinations at entry for screening quality applicants (Dahis et al, 2020).

iii. Improving management practices can have large impacts on public-sector productivity, as public sector managers make decisions over the allocation of resources (both physical and human) and how to incentivize and motivate staff. For example, Rasul and Rogger (2016), studying the Nigerian civil service, find that management practices in public organizations significantly influence productivity, measured in terms of project-completion rates. Recent evidence highlights the effectiveness of training, mentoring, and consulting interventions for improving the quality of management in organizations (McKenzie and Woodruff, 2020).

iv. Implementing GovTech solutions in government can help significantly reduce costs by improving information flows, such as in the case of e-procurement (Lewis-Faupel et al, 2016); and by improving monitoring systems, leading to a reduction in fund leakages, corruption and poor performance, such as in the case of e-financial management tools (Banerjee et al, 2020) and technologies for improved monitoring of teachers and healthcare workers (Duflo et al, 2012, Callen et al, 2020).

v. Financial and non-financial incentives can motivate staff to reach and maintain a high level of productivity. Financial incentives that pay for performance have been shown to be effective at raising productivity in the public administration, such in the case of tax-collection in Pakistan, where revenues increased by 50 per cent as a result of monetary incentives for collectors (Khan et al, 2016).

4] CONCLUSION

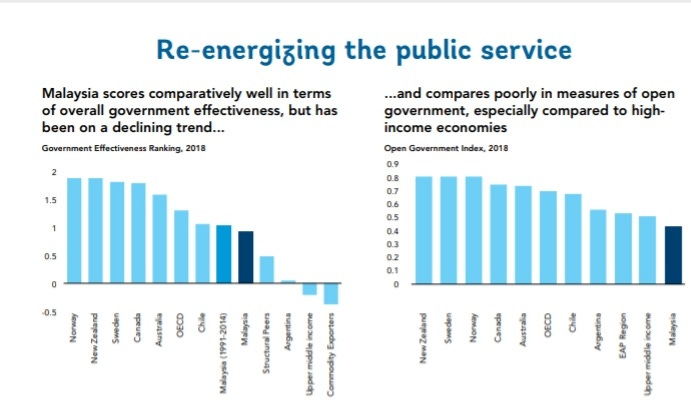

Malaysia has been under the World Bank’s consultancy, implementation and supervision of economic development projects since 1960s, and by participating in the World Bank’s Worldwide Bureaucracy Indicators (WWBI), a global dataset on public sector employment and wages covering 132 countries, Malaysia may hope to better benchmark various aspects of her public sector against comparator economies.

Further, by combining the WWBI with, for example, data from the Worldwide Governance Indicators and the World Values Surveys, a richer picture of the correlates between public sector investments, the quality of governance, and citizens’ attitudes towards government could possibly be drawn.

Whether the country can really aim high to achieve high growth (World Bank, 2021) or merely catching up (World Bank, 2022) is the daunting task of a capital-ethos, entrapped financialisation capitalism economy swirling in an ethnocapital-centric clientele-rentier relationship while wallowing within a kleptocratic capitalism domain seeking, craving and needing to gain unsavoury monetary entitlement rather than to improve the administration of its civil service deliverance.

The constant and often, continuous, offering cash increments to civil servants without due, appropriate and quality public goods and services deliverance is more than grave and hurtful injustice to every rakyat2.

Over the years, various efforts have been undertaken to improve public sector productivity in Malaysia, but not unsurprisingly, with limited resultant outcomes. Core difficulties often lie in translating researches on public sector productivity findings into policy actions. The elements constraining effort on improving public sector performance centre on administrative human-resource incapacity, a broadbase corruptive regime with burden of privileges mentality, a lost community soul living in a society laced with serial systemic odious practices, including

Over the years, various efforts have been undertaken to improve public sector productivity in Malaysia, but not unsurprisingly, with limited resultant outcomes. Core difficulties often lie in translating researches on public sector productivity findings into policy actions. The elements constraining effort on improving public sector performance centre on administrative human-resource incapacity, a broadbase corruptive regime with burden of privileges mentality, a lost community soul living in a society laced with serial systemic odious practices, including

You must be logged in to post a comment.