15/02/24

first posted on 23/04/2023

[Additional embedded referenced-sources on 18/2/24]

1] INTRODUCTION

By financialization capitalism we shall mean an emerging form of capitalism that increasingly uses finance, and apply financial tools and means, in the operations of capitalism (John Bellamy Foster, The Financialization of Accumulation, Monthly Review vol:62, issue 05 October 2010), or simply as the financialization of the accumulation of capital process (Paul Sweezy, “More (or Less) on Globalization,” Monthly Review 49, no: 4 (September 1997).

The defining process of accumulation in financial capital would involve the investment of money or any financial asset to increase the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form of profit, rent, interest, royalties or capital gains.

This shift in economic activity from production, and in the service sector, to financial activities that generate high private rewards disproportionate to their social productivity (as stated by James Tobin, Nobel Prize in Economics 1981) is one central aspect whereby the surplus value, that is, the added value created by workers in excess of their own labour-cost is being appropriated by the new financial capitalists as profits, (Marx, The Capital, chapter 8). This surplus value as the source of society’s accumulation of fund or investment of fund, part of is re-invested, but part of it appropriated as personal income, and used for consumption purposes by the owners of capital assets. The workers cannot capture this benefit directly because they have no claim to the means of financial creation or its final production.

2] MONOPOLY-FINANCE CAPITALISATION

The creation of monopoly-finance capitals in the neoliberalism economy of Malaysia is no more than the hegemonic economic ideology in neoliberalism-is-neo-imperialism of the Thatcher and Reagan regimes reflecting the new imperatives of capital – especially by advancing IT-geared financial globalization planted in Malaysia as the engine of financialization capitalism model (Lena Rethel, Malaysian Capitalism, Rents, and Financialisation, University of Southampton, 2010; STORM April 2023, the financialization of capitalist system; csloh 2022, Concentration of Capital), whence increasingly, that specific

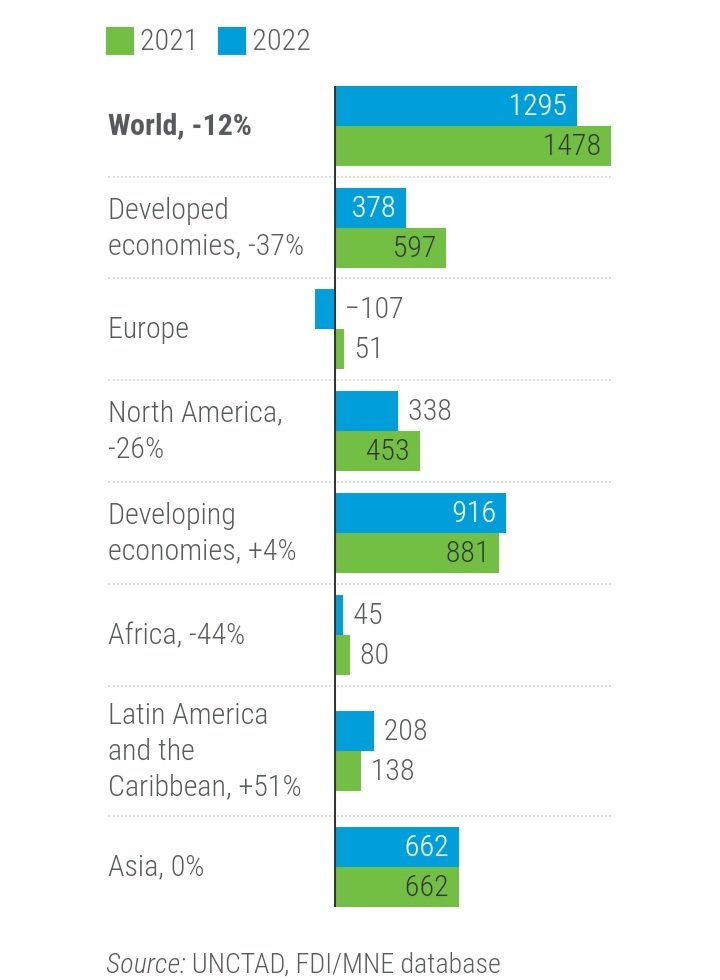

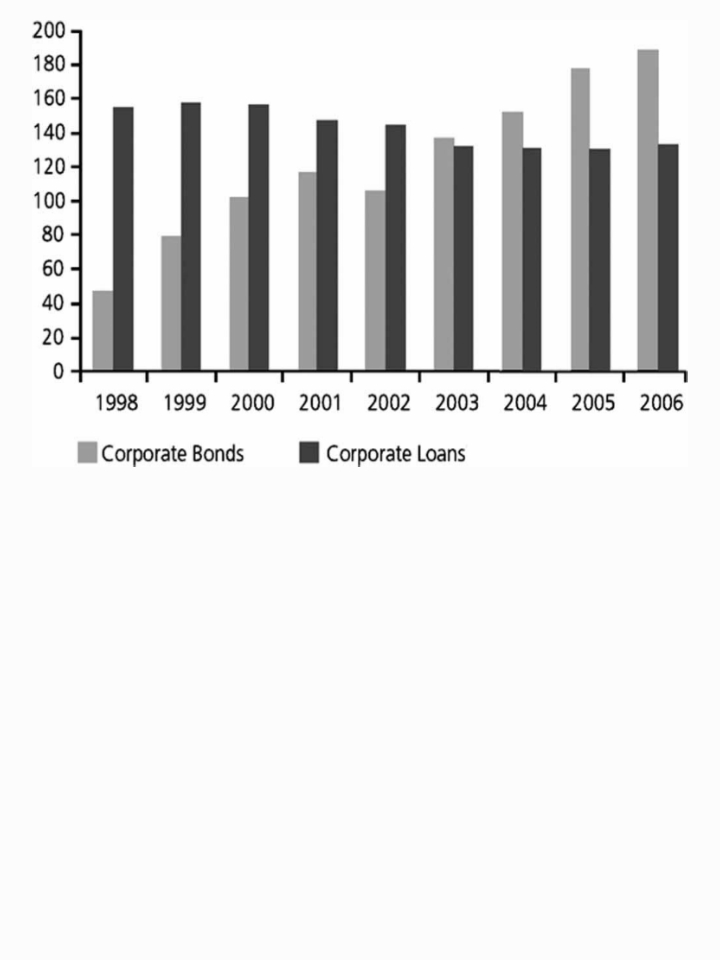

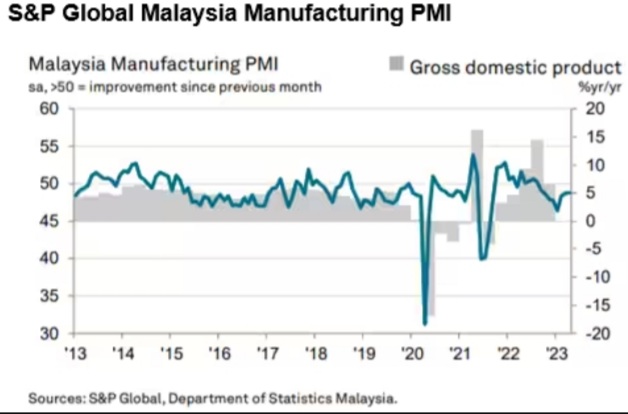

In the early 1990s, Malaysia corporations used to seek funds from the domestic equity market while non-financial enterprises relied on bank debt and the issuance of bonds abroad. Since 2003, however, the corporate bond market has reached an unprecedented size of RM$190 billion, while similarly since 1999 the total private sector bonds outstanding have surpassed that of public sector bonds (Bank Negara, 2007).

This expansion of bond finance favours bigger corporations linked to the government – much to the disadvantage of the Chinese and Indian capitals’ SMEs (the small and medium-sized enterprises) that do not have the sizeable funding resources, though presently, 98.5% out of the total 49101 establishments in Malaysia manufacturing sector are SMEs whilst the rest of 1403 companies are large firms, majority are the transnational corporations (TNCs); see STORM 2023, Industry 4.0 Initiative; STORM 2021, TNCs’ labour exploitation.

The ensuing financialization of Malaysian capitalism led to the emergence of a new politics of debts, and it also coincides with rising levels of household indebtedness (Geneva Graduate Institute, Global Challenges, issue 12, November 2022), globally reconfiguring society where share ownership and shareholder value take preeminence, a growing influence from capital market-based financial system, the further entrenchment of the political renter class power as well as the polarization of wealth and income – wealthy rich and poverty poors – especially with the explosion of financial innovation and trading that led an economy more towards “speculation” than the engenderment of production to be equally shared by rakyat (see Costa Lapavitsas, “The financialization of capitalism”, SOAS abstract).

The above processes occurred when the existing relationship between the various forms of capital rent-seekers collude. Under the New Economic Policy (NEP) with state capitalism this process only accentuated with increased financialization, reinforcing the existing strand of an ethnically divided capitalism (Searle 1999, Riddle of Malaysian Capitalism, Asian Studies Association of Australia). The country’s economic initiative was to be in alliance with the private sector, especially while in collaboration with Chinese capitals during the early 1980s, was also evidently prominent in the collusion of the privatization of state assets at that period, (Heng Pek Koon, The New Economic Policy and the Chinese Community in Peninsular Malaysia, The Developing Economics, 1997).

Whereas the majority of businesses built during the prewar period were found in the tin and rubber industries that comprised illustrious family firms built by Low Yat, Loke Yew, Chong Yoke Choy, H.S, Lee, Tan Chay Yan and Lau Pak Khuan who colluded with imperial British plantation interests to build their empires, the “new money-capital” entities like YTL Corp’s Yeoh Tiong Lay, Berjaya’s Vincent Tan, Genting’s Lim Goh Tong, Sunway’s Jeffrey Cheah, Lion’s William Cheng and the Ananda Krishnan groups and business stables attempted the forging of more Sino-Indo-Malay corporations, that is, a co-opetition strategy whereby Chinese and Indian capitals can compete as well as co-operate with Malay interests, (see Neo Yee Pan “The Role of Chinese Business in the Context of Our National Objective” paper delivered at the MCA Economic Congress, March 3rd. 1974; Jesudason 1989, Ethnicity and the Economy: the State, Chinese Business, and Multinationals in Malaysia, Oxford University Press, Singapore; Heng, op.cit.).

Those Chinese capitals and Indian compradors would, by forming joint ventures with Malay capitals, tap upon the vast capital resources of State agencies such as PERNAS, PNB and Peremba Bhd, besides

- UMNO-controlled corporations like the Fleet Group and Media Prima

- Institutional funds such as Lembaga Urusan Tabung Haji (LUTH or Islamic Pilgrims Management and Funds Board) and Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera (Armed Forces Funds Board)

- Private sector capital held by new class of Malay millionaires such as Tun Daim Zainuddin, Tun Sri Azman Hashim, Tan Sri Wan Hamzah and Tun Sri Rashid Hussein

- Royal entrepreneurs like Tunku Imran ibni Tuanku Ja’afar of Negeri Sembilan and Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar of Johore whose latter’s wealth estimated by Bloomberg is a conservative worth around US$5.7 billion, and the royal family’s due US$1.1 billion investment portfolio, which includes US$105 million worth of investments in public companies, US$483 million worth of investments in other private companies, and various real-estate projects.

Then, one has to look at the ordinary category of depositors who are redefined as fee-paying consumers of financial products such as car and motor-cycle hire-purchase loans and credit cards payment to consumer products besides those remitting housing mortgages.

Thus, in 2005, the ratio of total household debt to GDP amounted to 72.6%, of which nearly 85% was provided by banks (Bank Negara Annual Report 2006), and that between 1999 and 2006, total Malaysian household debt grew at an annualized rate of 15%. From a base in 2000 over RM$160 billion in household debt, this amount had risen over a short period to nearly RM$400 billion by 2006.

Consequently, the national domestic and external debt, between 1991 and 2011 soared:

What is beginning to happen is that compared to the NEP period, between 1970-1980, the bank-based development state model was that the consumption needs of households had been subordinated to the financing needs of the industrial sector as well as the ethnic-based distributive policy, that is the NEP, whereas post-economic downturn 1980s had seen private consumption (and thus household borrowing) is increasingly seen as the important driver of domestic growth. This also means that bank lending is much about sustaining consumption than that of production.

The fifth point is that the passing of the buck-ringgit, so to speak, is the “individualization of risk” had meant a high incidence of household debts arising from marketed consumption patterns whereby April 2006 the Credit Counseling and Debt Management Agency (AKPK) has to be established as part of the government approach – to develop a personalised debt repayment plan in consultation with financial service providers – to confront the ever increasing consumer debt that was primary affecting many in the Malay (youthful) community. Unfortunately, AKPK had often portrayed these debtors as “innocent victims of circumstances” or as “hapless” or being “foolish” whereas the main underlying and real reason is that the rising household debt owes too much kleptocratic capitalistic instinct to empower capitalism, and more recently the financialisation of capitalism by ethnocapital rentiers – whether enticing youths to possess new versions of motorcycles or a variety of credit-cards.

By March 2016, more than 148,000 borrowers have joined the debt management programme conducted by AKPK (Malaysian Reserve, May 25th. 2016).

Finally, public interest rates were driven to very low rate to enable such banks to make secure guaranteed profits by lending to their customers and households at higher rates. In short, the financialization of Malaysian capitalism had only encouraged public funds being injected into private and kleptocratic banks to boost capital and enlarge capital formation, and further where this public liquidity was to enable these banks to sustain their continuous siphoning operations.

Therein highlights the contradictions of poverty and inequality within society.

The other key point is that the rise of a ‘mass investment culture’ has strengthened the ‘dominance of finance capital’ (Harmes 2001, Mass investment culture?, New Left Review, 9, pp 103-24), and is a contributing trend in the financialization of capitalism in Malaysia today, too. Take as an example, PNB has also nowadays invests in bonds and structured instruments, thus assisting in the reproduction of a sustainable capital market-based financial system – a collateral vulnerabilities of increasing individual exposure to the capital market whereby inevitably “households had become financialized, too” (Costas Lapavitsas, Financialised Capitalism: Crisis and Financial Expropriation, Historical Materialism 17 (2009), School of Oriental and African Studies, London).

In effect, the evolution of unit trust investment, on one side though deviating from NEP redistributive schemes, has on the other hand, turns the capital markets as part of social policymaking, too. By October 2008, the ruling regime borrowed RM$5 billion to shore up the credit-crunch-affected equity market, with the money provided by EPF but disbursed by Khazanah jointly owned by EPF, PNB and Khazanah itself.

Thirdly, this shore up of government interests (not dissimilar to crony capitalism in the early stage of the NEP implementation during the 1970s) that only act as a political behaviour to protect the up-and-coming Malay middle class (Embong, State-led Modernisation and the New Middle Class in Malaysia) and the Barisan Nasional clientel, but also as a conduit on preserving the wellbeing of the capital market so as to be used to bail out Malaysian corporations and favoured individual capitalists.

As the state’s role was being transformed to meet the new imperatives of financialization, the kleptocratic governance had to assume as lender of last resort–bailing out crony capitalists like Malaysian Airline System’s Tajudin and Halim Saad’s United Engineers Malaysia (UEM) and the Renong Group (the largest bumiputera-owned conglomerate then) when in August 2001, Syarikat Danasaham – the wholly subsidiary of state-owned investment house Khazanah Nasional – made a conditional voluntary offer to purchase the entire shares and warrants of UEM, including Renong’s stake.

Lastly, PNB evolution from changing state investment practices to assume increasingly a role as ‘market players’ where the investment strategy has become more neoliberal following financial considerations on return-oriented basis, there is a competitive stance in maintaining, and retaining, share of the market than that of a distributive expression as articulated within the 1970s’ NEP objectives. It started as a state investment vehicle to strip off government assets for private Bumiputera interest. Using these ill-gotten funds, by 1981, PNB has had became one of the leading Bumiputera investment institutions acquiring RM$487 million shares in 60-odd companies.

3] ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT REVISIONISM

With this expanded capital base, the 1980s economic development revisionism only contributed to the seedling of fund that eventually induced the introduction of financialization capitalism in the country. For example, PNB has together with Khazanah, implicated in the launch of the “transformation programme for government-linked companies”. For instance, Pemandu (Performance Management Delivery Unit) was set up under the Prime Minister Department on Sept 16, 2009 to oversee the implementation of the Economic Transformation Programme (ETP) and the Government Transformation Programme (GTP), the two key pillars of the government’s New Economic Model (NEM) introduced in 2010.

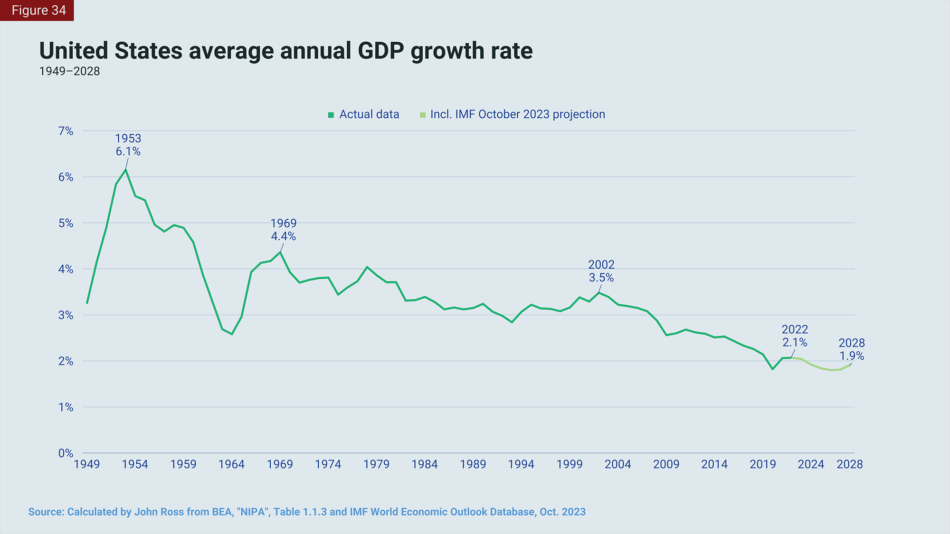

Secondly, the reforms heralded by Prime Minister Najib in 2009 and implemented by Idris Jala, Minister in the PM’s Department heading the Performance Management and Delivery Unit (Pemandu) have been lackluster, and not as successful in their implementation as often propogated (Research for Social Advancement (REFSA), A Critique of the ETP, Part I and Part II, January 2012). According to other analyses of the 12 national key economic areas that Pemandu targeted upon, they averaged lower gross national income growth than non-key sectors between 2011 and 2014 at 4.99 percent against a national average at 8.77 percent.

These state-funded vehicles, instead of overseeing the New Economic Model progress, have willingly driven public funds being routed into the banking system to boost capital. With the availability of ready liquidity of public fund, the consolidated domestic banks nowadays are able to more than sustain their profitable operations.

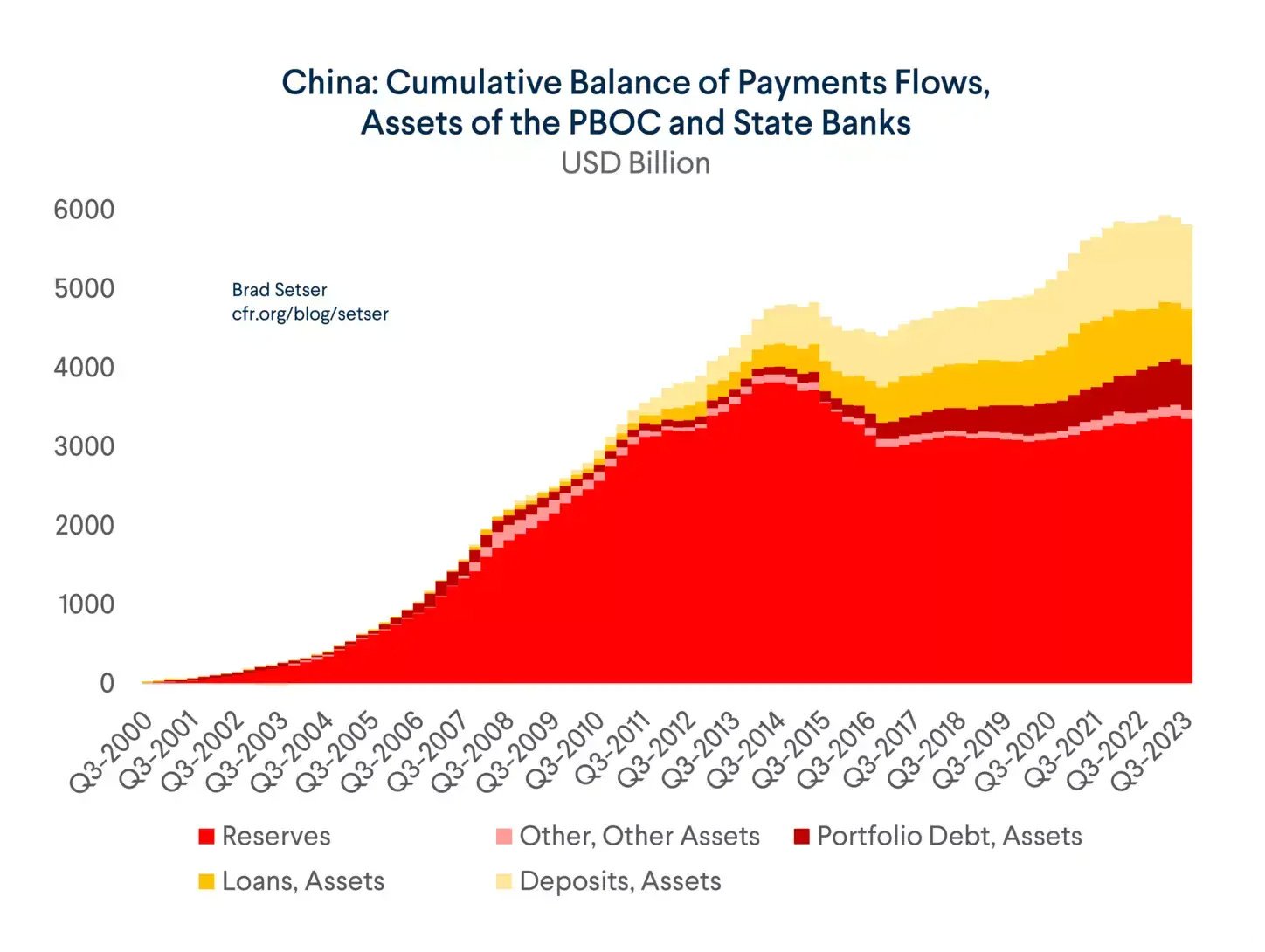

The third pointer is that public interest rates – by which the central bank in hoarding dollar reserves, Bank Negara is able to “sterilize the reserves” – are being driven down to enable the banking system to make secured profits by lending to their clienteles at higher rates.

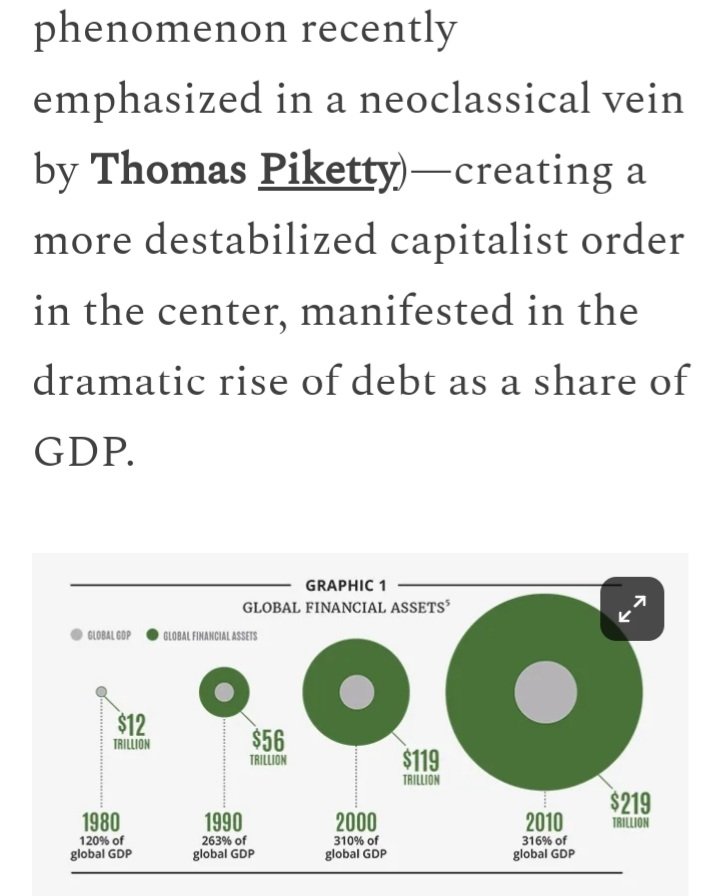

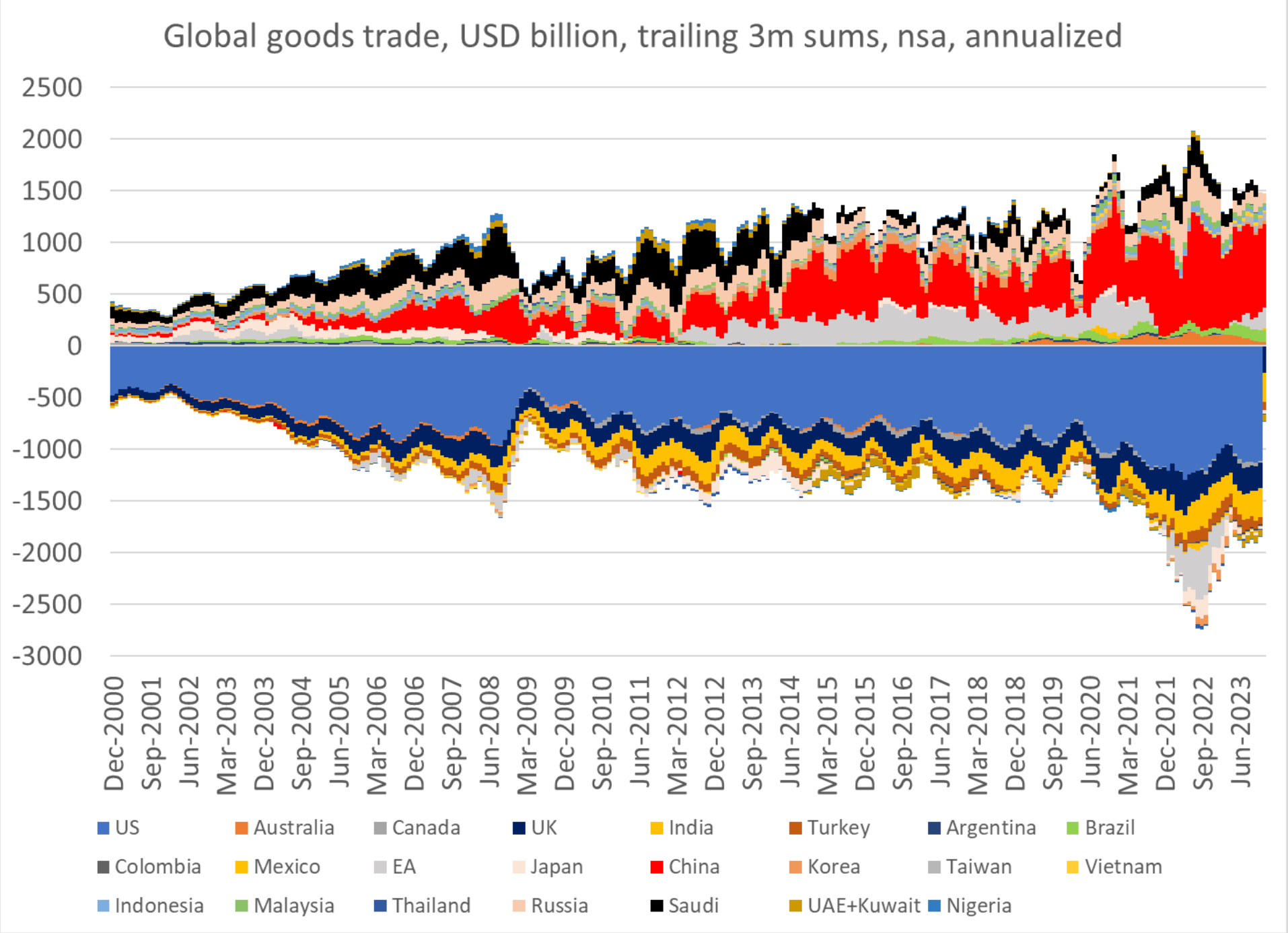

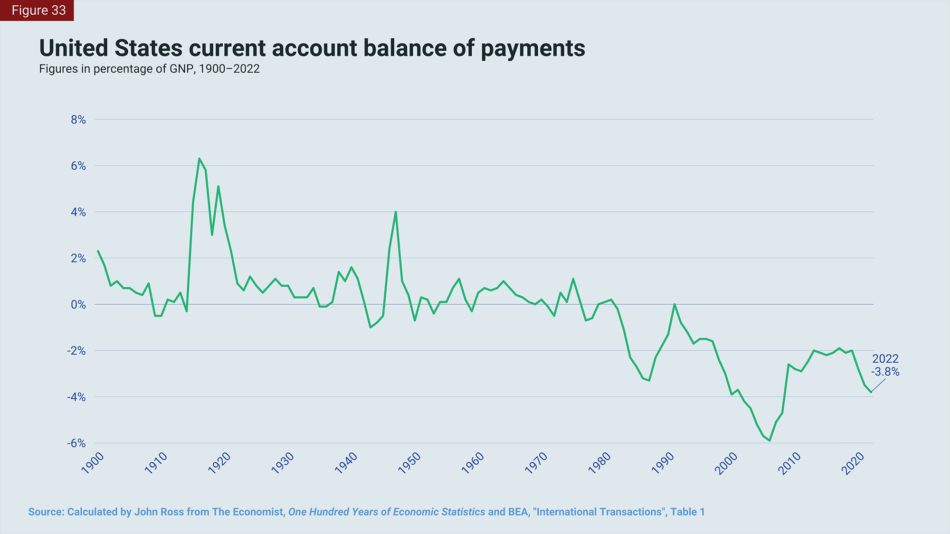

4] GROWTH OF FINANCIALISATION OF WORLD ECONOMY lies in the deeper imperial penetration into underdeveloped economies with wider financial dependence, (see Magdoff 1978, Imperialism: From the Colonial Age to the Present and Magdoff, 1969, The Age of Imperialism; also refer to Foster “The New Imperialism of Globalized Monopoly-Finance Capital – An Introduction”, Monthly Review, Vol:67, Issue 03), like in Brazil and Venezuela where the domination of global monopoly-finance capital has attracted portfolio investment, and to pay off its external debts to international capital, including the IMF that accrued high interest rates, de-industrialization, a slow growth in its economy, and the continuance vulnerability to the often rapid movements of global finance (IMF, World Economic Outlook, 2015; csloh, destined-to-debts; ks jomo, IMF-deepening-world-stagnation; csloh, debt-crisis-threatening-Global-South).

The daily average volume of foreign exchange transactions, even from old data set had indicated the magnitude the seriousness and depth of neo-imperial financialization penetration: US$570 billion (1989) had increased to US$2.7 trillion by 2006, and US$5.7 trillion in 2013 (Bank of International Settlements, various reports). Therefore, the agglomeration of wealth, and its continuous transferring across the globe, had pointed to the increasingly related to finance transactions than the physical material mode of production. It also indicative in some ways through transfer-pricing by trans-national corporations (TNCs) that there is a constant leaking of investment fund from Malaysia, and there is consultancy advisory on how to minimize it (see Juliana Tan Ming Qing, Malaysia: Transfer pricing aspects of restructuring, KPMG 2014; Bob Kee and Mei Seen Chang, Malaysia: Malaysia’s evolving transfer pricing landscape, KPMG 2014).

Rich countries has had drained US$152Trillion from the Global South since 1960.

Imperialism never ended, it just changed form.

5] THE FINANCIAL SUPERSTRUCTURE STRANGLING HOMEOWNERS

The financial superstructure’s demand for new cash infusions to keep speculative financial derivatives expanding (see Foster “The Financialization of Capitalism”, op.cit.), has meant that it encourages homeowners to maintain their lifestyles even with stagnant real wages that are causing the Malaysia’s household debts being the highest in Asia – as at August 2015, the country’s household debt-to-GDP ratio stood as high as 88.1% (The Edge 22/02/2016; by March 2016, the total household debt in Malaysia stood at 89% of the Gross Domestic Product or RM$1 trillion, consisting 80% from the banking system, with 20% from non-banking financial institutions, Malaysian Reserve, 26th. May 2016); whereas, collectively, the 9 richest men in Malaysia have a total capital asset of RM$175 billion (Forbes 2016).

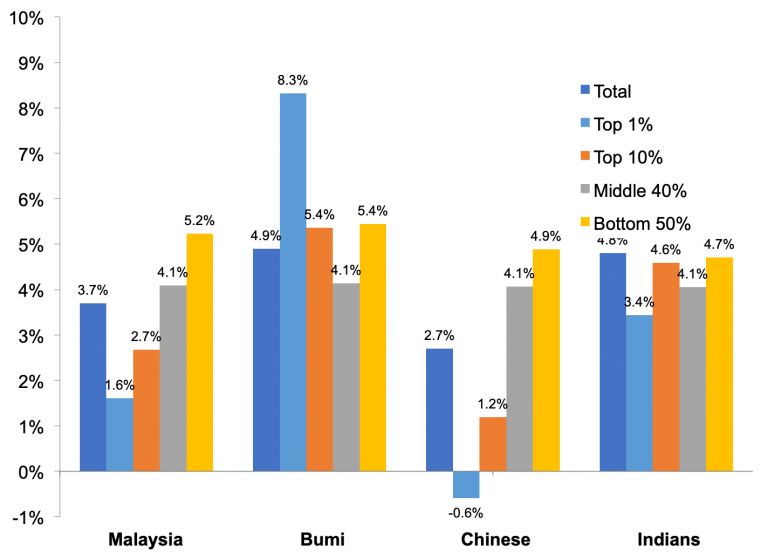

Existing data have also signified that the rapid increase in inequality have become built-in necessities of the monopoly-finance capital phase in the neo-imperialism system. The wealth gap among Malay Malaysians has grown larger significantly with the Gini Coefficient among the bumiputeras having the highest inequality (Hwok-Aun Lee and Muhammad Abdul Khalid, Is inequality in Malaysia really going down?, Faculty of Economics Administration Working paper 2014/09, University of Malaya).

This is duly noted by the Khalid research paper at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where presented, the disparity among the Malay community – the top 1% – is much acute, and accentuated as ever.

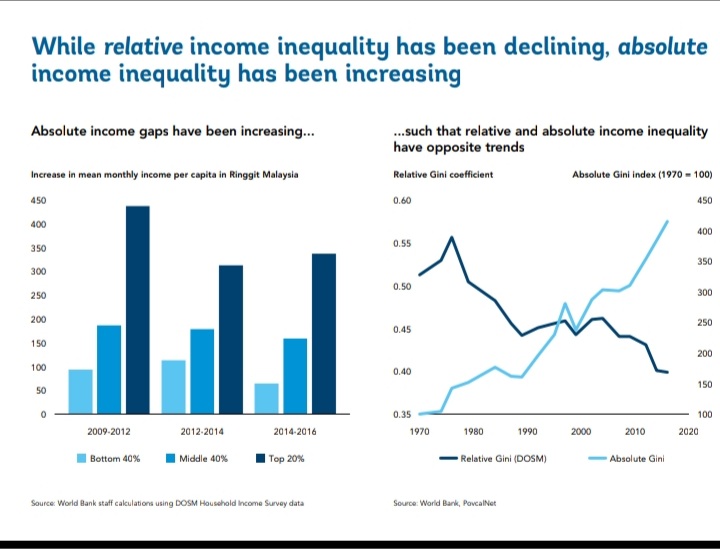

After six and half decades of sustained neoliberalism economic developmental effort, the nation of Malaysia is still as disparity in absolute income inequality as ever, (see lower right chart below)

Sources: World Bank datasets and DoSM statistics

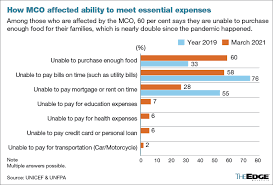

It is also an era of a generation when 70% of lower-income households cannot even meet monthly basic needs – indeed, more than 60% of these households reported having no savings at all – not much of a difference than 10 years ago:

According to the Employees Provident Fund, over two million contributors aged between 40 and 54 have less than RM10,000 in their retirement savings accounts; and

where increasingly these household expenditures are expansively spent on food:

Thus, the nation of Malaysia is still encasted in acutely absolute income inequality as ever:

As an instance, Bantuan Tunai Rahmah, the cash aid scheme, reportedly has 8.7 million recipients – a quarter of the population – which gives a damning statement on the extent of low incomes among our workers.

Indeed, an UNHDP Report shows that the richest 10% in Malaysia control 38.4% of the economic income as compared to the poorest 10% who control only 1.7%.

Related Readings

Financialisation of the Capitalist System

Unequal Exchange under Neo-Imperialism

Financialisation capitalism deepening neoimperialism penetration

Financial imperialism – the globalisation of monopoly-finance capital

You must be logged in to post a comment.