15/02/24

1] INTRODUCTION

In his chapter on “The Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist” in the first volume of Capital, Karl Marx placed special emphasis on the notion of colonialism proper — that is, settler colonialism (from the Latin colonus, meaning settler). In his words, “The treatment of the indigenous population [of the Americas] was…most frightful in plantation-colonies set up exclusively for the export trade.…“.

The actual situation is that large-scale plantations supplied consumption commodities such as coffee, sugar, cotton, and tea – and the rubber latex tapped as rolls of caoutchouc and balls of rubber – known as “niggerheads” from their alleged resemblance to the skulls of black people – arrived in Europe aboard returning slave ships where England had a 33 percent total share of the slave-trading in the Caribbean West Indies and North America in 1673 and 74 percent by 1683; indeed, the Royal African Company, under the ruling arms of the British Crown, owned and controlled 90 percent of the African-slave share by 1690. The transatlantic slave trade allowed for both elimination of Indigenous peoples and the insertion of a racialized Black body marked as slave labour.

From the explicit exploitation of the dark and brown proletariats comes the Surplus Value filched from human beasts’ hearts and souls, Du Bois intoned: Black Reconstruction in America 1860–1880 (1935; repr. New York: Free Press, 1992), 15–16).

Marxist feminists like Claudia Jones in the 1940s and many others today argue that Black women face a triple or interlocking oppression when neither the induction to work nor the surplus value created by all workers is the same because capitalist exploitation is more intensive and brutal for workers of colour. Through the structural and historical framework of racial capitalism, it is determined that capital accumulation depends on this global racialised division of labour and who would eventually be disproportionately impacted, (Claudia Jones, An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman! (New York: National Women’s Commission CPUSA, 1949; read the other works of FEMALE black Marxist writers; Jean Alt Belkhir).

2] COLONIAL CAPITALISM

A few hundred years ago, colonial capital ploughing through our pristine forests opened up settlement plantations and mineral mines had brought about rubber latex and tin ores for new product consumption in the western hemisphere what is commonly referred to as the Global North. Under this imperial process, indenture labour and labour slavery were introduced to peninsula Malaya, Sarawak and British North Borneo:

The plantation system was based on the superexploitation of labour. Pay was so low that the English assistant Leopold Ainsworth wondered how the Tamil workers and their families could “possibly exist as ordinary human beings” on the wages paid on his boss’s Malayan plantation. In 1926, the cost of a Papuan indentured laborer was 20 percent of that of a white worker, 25 percent of that of an employed estate manager, and 10 percent of that of a white unskilled laborer. Racist humiliation, insult, and cruelty were part of the everyday lives of the coolies ( a humiliating term given to the local inhabitants ), while the pale-skin estate owner sipped at stengahs (whisky and sodas) clad in sweatstained khakis, summoning a “boy” with a teapot or gin bottle to the veranda at the end of another hot and humid day with the topee on his head.

It was during a time in the 15th century that the Roman Catholic Church divided the world in half, granting Portugal a monopoly on trade in West Africa and Spain the right to colonize the New World in its quest for land and gold. Pope Nicholas V buoyed Portuguese efforts and issued the Romanus Pontifex of 1455, which affirmed Portugal’s exclusive rights to territories it claimed along the West African coast and the trade from those areas. It granted the right to invade, plunder and “reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.” Queen Isabella invested in Christopher Columbus’s exploration to increase her wealth and ultimately rejected the enslavement of Native Americans, claiming that they were Spanish subjects.

Spain established an asiento, or contract, that authorized the direct shipment of captive Africans for trade as human commodities in the Spanish colonies in the Americas.

When the Spanish conquistadors reached the shores of The Philippines in 1521, the people of Mactan, led by Lapu-Lapu, resisted. Magellan burnt down their villages after they resisted demands for tribute as well as accepting his god and king.

Eventually other European nation-states — the Netherlands, France, Denmark and England — seeking similar economic and geopolitical power joined in the trade, exchanging goods and people with leaders along the West African coast, who ran self-sustaining societies known for their mineral-rich land and wealth in gold and other trade goods. They competed to secure the asiento and colonize the New World. With these efforts, a new form of slavery came into being. It was endorsed by the European nation-states and based on race, and it resulted in the largest forced migration in the world: Some 12.5 million men, women and children of African descent were forced into the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The sale of their bodies and the product of their labor brought the Atlantic world into being, including colonial North America. In the colonies, status began to be defined by race and class, and whether by custom, case law or statute, freedom was limited to maintain the enterprise of slavery and ensure power.

Even presently, as an instance, thirty percent or more of Congolese cobalt mining is “artisanal”. By sourcing copper in an artisan manner (ASM), it is no more than miners using rudimentary tools and work in a most hazardous condition to extract dozens of minerals andll South. Because ASM is almost entirely informal, artisanal miners rarely have formal agreements for wages and working conditions. There are usually no avenues to seek assistance for injuries or redress for abuse. Artisanal miners are almost always paid paltry wages on a piece-rate basis and must assume all risks of injury, illness, or death,(review Cobalt Red).

This extraction – and exploitative – process is no more any different from the Great Powers colonialism era on their forward movements to exploit raw resources in Africa, Asia and south America where in the latter continent between 1849 and 1874, over 90,000 Chinese workers were contracted to be shipped to Peru. Around 10 percent of those transported died during the voyage across the Pacific. Besides working on plantations or railroads, the most unfortunates were sent to work in the guano pits, where they were forbidden to leave the islands. The total workforce fluctuated between 200 and 800 Chinese workers; new workers simply replaced those who died, given the extensive coolie labour system, (Michael J. Gonzales, “Chinese Plantation Workers and Social Conflict in Peru in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Latin American Studies 21, 1955: 385–424).

It involved grueling physical labour by males, using picks and shovels to extract the guano from the mountainous deposits, loading wheelbarrows and sacks, and transporting the manure to chutes for loading boats. Each worker was expected to load five tons of guano each day. Behavioral infractions and failure to meet daily quotas were met with physical punishment. The work was exhausting; the stench was overwhelming; and guano dust coated everything, penetrating the eyes, noses, and mouths of the workers. Opium was imported in an attempt to prevent further revolt and suicides among the workers, (see Lawrence A. Clayton, “Chinese Indentured Labor in Peru,” History Today 30, no. 6, 1980: 19–23); Alanson Nash and contemporary witnesses reflecting on these conditions, elaborated, “once on the islands a Chinaman seldom gets off, but remains a slave, to die there…….They were seen as expendable beasts, forced to “live and feed like dogs.”

An account, in the Christian Review noted that “the subtle dust and pungent odor of the new-found fertilizer were not favorable to inordinate longevity.” Guano labour involved “the infernal art of using up human life to the very last inch,” in Chinese Coolie Trade, Christian Review, April 1862; The Chinese Coolie Trade, 1862; see also Basil Lubbock, Coolie Ships and Oil Sailers, Glasgow: Brown, Son and Ferguson, 1955, 35; Charles Wingfield, The China Coolie Traffic from Macao to Peru and Cuba, London: British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 1873.

Even after slavery was abolished, millions of people in the Global South still fell victim to the continuing worst of the “free” marketplace. Even after the Second World War, when decolonization led to the end of the so-called “Golden Age of Capitalism,” new liberal economics’ adventurers returned boldly to rob again the wealth of Global South during an era known as neo-colonialism.

3] NEO-COLONIALISM

Michael Morgan in his contribution in Malaya: The Making of a Neo-Colony – (edited by Malcolm Caldwell and Mohamed Amin is a collection of articles with a socialist analysis of Malayan History from 1874 to independence) – pointed out Malayan rubber alone in 1947 earned for Britain US$200 million in comparison to US$180 million earned by all its manufactured exports.

To get some perspective on the magnitude of the US$200 million in 1947 which the British earned from the sale of Malayan rubber to the US, it would be more than 2 billion dollars (US$2,337,051,162) in today’s value, or more than 9 and a half billion ringgits (RM$9,544,012,524).

Bearing in mind the total national expenditure budget in the 2000s was averaging RM$42 billion, you get a sense of the scale of exploitation. That was in that one year alone and only for the one product.

By 1951, the rubber export from Malaya to the United States was estimated to be 370,000 tons valued at US$405,000,000. Britain’s total manufactured exports to the US in that year earned US$400,000,000 – again less than its earnings from Malayan rubber. (Natural Rubber News, January 1952, p 1, cited in Li Dun Jen, British Malaya. An Economic Analysis, InstitutAnalisa Sosial., Kuala Lumpur, 1982).

In today’s value we would be looking at such a figure as US$3,913,000,000 or over RM$18 billion.

Indeed, The Annual Report of the Federation of Malaya for 1948 reported “…of the world’s total output of rubber and tin in 1948 this country produced 45.8 per cent of the former and 28.1 per cent of the latter. This achievement afforded more assistance to the UK and Commonwealth in terms of gold and dollars earned than was afforded to the UK and Commonwealth in terms of gold and dollars earned by the total export drive of Great Britain over the same period.

By way of a fact, in the 1949 annual report of the Lenadoon Rubber Estates, Sir Eric Macfadyen observed: “…rubber is of more importance to the British economy than Marshall Aid. Last year Malaya alone produced just about 700,000 tons. The USA imported from the country over 450,000 tons…Every penny in the price per pound up or down means about US$17 million in our balance of trade.”

What is often neglected to mention – until Gordon and Jomo set to dissect archived colonial records – is that besides the raw materials extraction were taxes levied, land and mining concessions gained, opium sales, and dividends paid that were administered by the British raj who as a regime of expatriates having

its control over the colonial state that metropolitan capitalism is able to control, subordinate and exploit the colony society which

served as a channel for surplus appropriation or wealth draining, (Chandra 1980: 278).

Indeed, Utsa Patnaik has calculated the British Raj siphoned out at least

£9.2 trillion, or US$44.6 trillion from India, whereas the UK’s GNP before the pandemic and ‘Brexit’ was a mere US$3 trillion. The estimated colonial contributions to the UK’s dollar pool were at US$2,115 million for 1946-52; thus, Malaya alone contributed US$1,475 million, or 70 per cent of British domestic budgetary, (Gordon and Jomo, ibid.)

That nugget of neoliberal policy paradigm, however, favours expanding the scope of markets – including global markets – by restricting the role of government action that failed. It widened inequality in and within nations, avoid promoting the climate transition, and in fact neglecting a range of global issues from public health, education, social welfare to supply-chain resilience, (so expressed by Dani Rodrik of Harvard).

4] ETHNOCAPITAL COLONIALISM

Even after post-independence, emerging clientel ethnocapitalism replaced colonial racial capitalism by enforcing drastic bad union-bursting labour measures on the working rakyat2, in an imputation of neo-colonialism; see also, Bhopal, University of North London; and STORM’s Rentier Capitalism in Accumulation, 2021).

By ethnocapital we mean a (malay) bumiputra owned and controlled an entity performing under a rentier or clientel capitalism approach whether it is a public agency, a government-linked company (GLC) or a privatised and or commercial enterprise.

On this exploratory enquiry we are to delve on the power or dominance relations among persons, their subsumed class to entitled positions that enforce political power which defines economic dominance and social status deference.

Between the dominating and the dominated, under capitalism the capitalists

are dominant at each level, the proletarians are dominated at each.

5] CAPITAL AND CLASS

Neoclassical theory premises on individual preferences, resource endowments and technological capability, while Marxian theory begins with class and class processes.

Nicos Poulantzas conceives a concept of class “places” as distinguished from class positions where “places” exist at each of the these levels of society: economic, political, and ideological (or cultural) levels where at the latter, social dominance regards bumiputeras status and on an islamic allegiance, for instance.

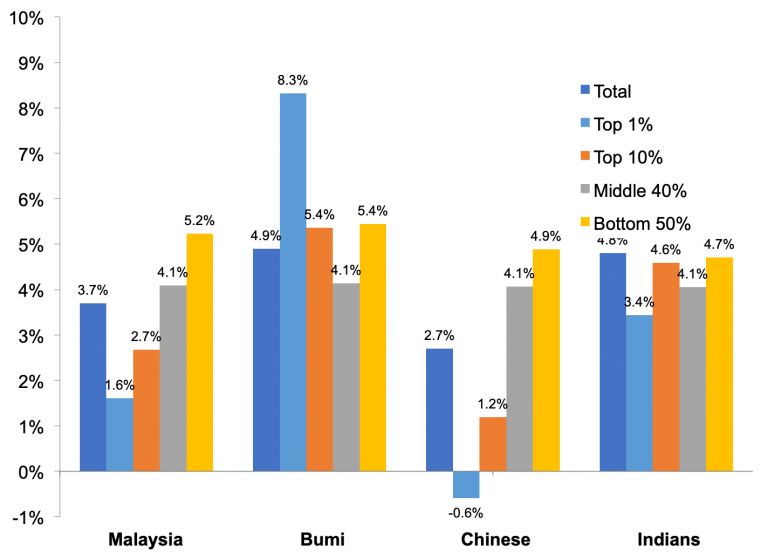

The issues relating to where the economic power emits from could be identified from the stronghold of clientelism and the ensuring political clientel relationship where ruling elites in the United Malay National Organisation (UMNO) [place] had aligned with economic oligarchs [positions] in accepting rentier capitalism to sustain their hold on [power]. They adopt this clientelism as solicitations for votes at the grassroots level, allowing ruling elites [place] the party patronage [position] and political [power] to “effectively partisanizing them and ensuring ground-level officials with whom most voters interacted with ……are political party loyalists” (Weiss, 2020), resulting in the skewed distribution of profits by political stakeholders and the stark inequality of wealth permeating in the country (Khalid):

Bumiputera in the top income groups (the top 1 per cent and the 10 per cent) benefited the most from economic development and its ensuing growth

There is every reason to say that patronage position is never moved from place prescence of ruling elite and the political power that oozes. Indeed, ruling elites are the biggest “owners” of divisional-level of UMNO constituency places with the office-bearing posts that defined political positioning posts with the ensuing power distributing spoils that emit therefrom. This is similar to what in management term that owners and managers if are taken as a whole, are elements of the same class. Their differences on this issue are of degree and not of kind. The ownership of the place loci, by situating in a position, the control of vested power elements is explicit.

The two class processes of capitalism are defined as the extraction and distribution of surplus labour in the form of value. The class positions of the capitalist fundamental class processes are productive workers (performers) and productive capitalists (extractors). Capitalists appropriate surplus value from the consumption of labour power during the production of commodities. The surplus is distributed among occupants of subsumed class positions associated with say the state, merchants, financiers, landlords, managers and monopolies. Therefore, class position is determined by the relationship of the individual to the appropriation and distribution of surplus value.

That positioning presupposes a “place” is already in place or existence – as a political party or as an enterprise entity.

It needs to be emphasised that financial control is merely the outcome of the process of capitalist reproduction. On the one hand, the gradual concentration and centralization of capital forces corporations to rely, over time, on the large pools of capital made available by financial institutions. On the other, the ups and downs of the business cycle force the corporation to rely on external capital at critical conjectures in its development.

Thereby, the value of the state of a nation lies on political stability, a performing economic outlook and achievable results with due inflow of economic developmental funds both domestic and foreign investments, a pulsating economy sustainable within competitive market conditions while reducing wastage and eradicting odious practices so as in generating confidence all-around when rakyat² are happy, educated and knowledge-imbued in excelling productivity towards the common goodness – and betterment – of the country in the sharing of a common wealth.

Related Readings

Colonial Capitalism and clientel ethnocapitalism

Imperialism, Globalisation and its Discontents

Unequal exchange under Neo-Imperialism