Collective of Geoeconomics

14/11/23

PREAMBLE

This article is re-published from Adam Tooze Chartbook #245, Nicolas Pelham’s account, Tannira (2021) essay in The Political Economy of Palestine; additional, comments from Wilson Centre, Council for Foreign Affairs and the New York Times illustrations; with datasets from UNRWA and UNCTAD

I] INTRODUCTION

Resourceful people confined in such desperate circumstances resort to extraordinary makeshifts. In Gaza, the most remarkable phase of the struggle for survival and prosperity came with the era of the “tunnel economy”.

Today we hear of tunnels mainly in a military context or as places to hold hostages. Gaza’s tunnel system began first and foremost as a means of economic survival to gain access to Egypt.

II] TUNNEL ECONOMY

Nicolas Pelham’s account of the emergence of the tunnel economy from the Journal of Palestine Studies in 2012 is worth quoting at length:

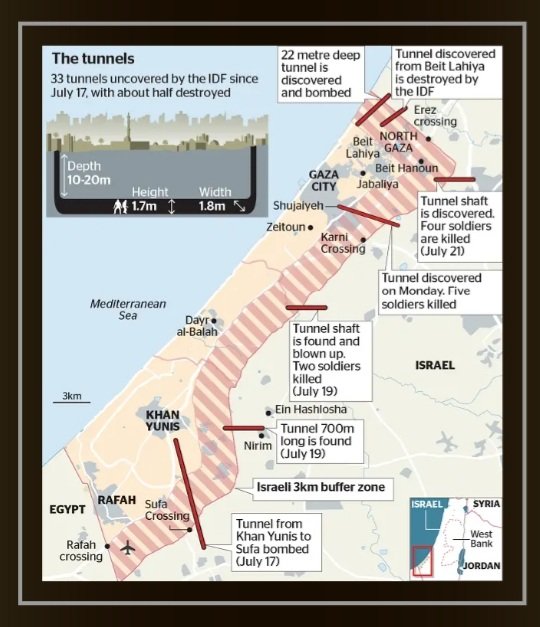

Hamas’s summer 2007 military takeover of the Strip marked a turning point for the tunnel trade. The siege, already in place, was tightened. Egypt shut the Rafah terminal. Israel designated Gaza “a hostile entity” and, following a salvo of rocket-fire on its border areas in November 2007, cut food supplies by half and severed fuel imports. In January 2008, Israel announced a total blockade on fuel after rockets were fired at Sderot, banning all but seven categories of humanitarian supplies. As gasoline supplies dried up, Gazans abandoned cars on the roadside and bought donkeys. Under Israeli blockade at sea and a combined Egyptian-Israeli siege on land, Gaza’s humanitarian crisis loomed, threatening Hamas’s rule. The Islamists’ first attempt to break the stranglehold targeted Egypt as the weaker link. In January 2008, Hamas’s forces bulldozed a segment of wall at the Rafah crossing to allow hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to pour into Sinai. While long pent-up consumer demand was released, the measure provided only short-term relief. Within eleven days, Egyptian forces succeeded in herding Palestinians back. Egypt then reinforced the army contingent guarding the locked gates and built a fortified border wall. As the siege intensified, employment in Gazan manufacturing plummeted from 35,000 to 860 by mid-2008, and Gaza’s gross domestic product (GDP) fell by a third in real terms from its 2005 levels (compared to a 42 percent increase in the West Bank over the same period).6 With access above ground barred, the Islamist movement oversaw a program of industrial-scale burrowing underground. With each tunnel costing $80,000 to $200,000 to build, mosques and charitable networks launched schemes offering unrealistically high rates of return, promoting a pyramid scheme that ended in disaster. Preachers extolled commercial tunnel ventures as “resistance” activity and hailed workers killed on the job as “martyrs.” The National Security Forces (NSF), a PA force reconstituted by Hamas primarily with ’Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades (IQB) personnel, but also including several hundred (Fatah) PA defectors, guarded the border, occasionally exchanging fire with the Egyptian army, while the Hamas government oversaw construction activity. Simultaneously, the Hamas-run Rafah municipality upgraded the electricity grid to power hundreds of hoists, kept Gaza’s fire service on standby, and on several occasions extinguished fires in tunnels used to pump fuel.

As Mahmud Zahar, a Hamas Gaza leader, explained, “No electricity, no water, no food came from outside. That’s why we had to build the tunnels.”

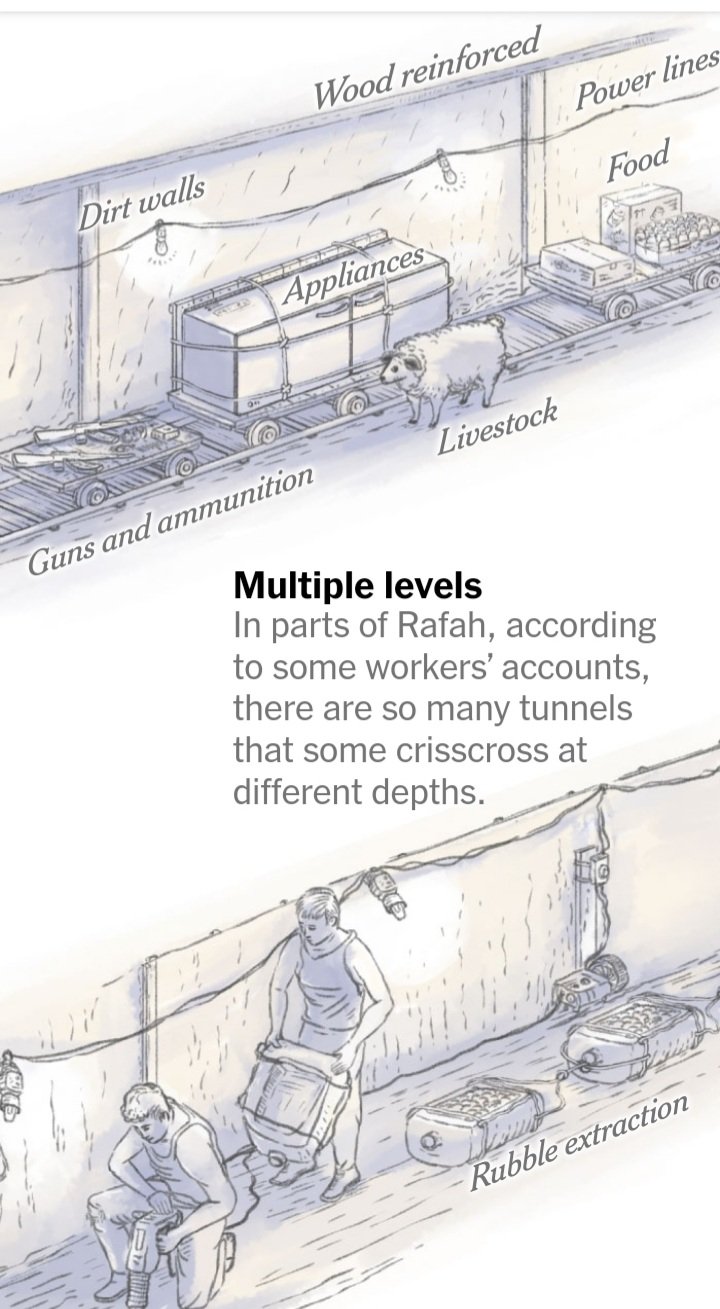

Private investors, including Hamas members who raised capital through their mosque networks, partnered with families straddling the border. Lawyers drafted contracts for cooperatives to build and operate commercial tunnels. The contracts detailed the number of partners (generally four to fifteen), the value of the respective shares, and the mechanism for distributing shareholder profits. A typical partnership encompassed a cross-section of Gazan society, including, for example, a porter at the Rafah land crossing, a security officer in the former PA administration, agricultural workers, university graduates, nongovernmental organization (NGO) employees, and diggers.

Abu Ahmad, who had earned NIS 30–70/day as a taxi driver, invested his wife’s jewelry, worth $20,000, to partner with nine others in a tunnel venture. Investors could quickly recover their outlay. Fully operational, a tunnel could generate the cost of its construction in a month. With each tunnel jointly run by a partnership on each side of the border, Gazan and Egyptian owners generally split earnings equally. …. By the eve of Operation Cast Lead in December 2008, their number had grown to at least five hundred from a few dozen mainly factional tunnels in mid-2005; tunnel trade revenue increased from an average of $30 million/year in 2005 to $36 million/month. Mitigating to some extent the Gaza economy’s sharp contraction resulting from the international boycott of Hamas,

Hamas regulated the tunnel trade with a tunnel committee. It charged fees, organized security and regulated the types of good that were traded. As Tannira (2021) writes in the excellent collection The Political Economy of Palestine:

Under the trusteeship of Hamas, smaller businessmen were allowed to invest capital in the construction of mid-advanced tunnels to allow for the flow of goods and supplies. Tunnel workers (who were responsible for digging the tunnels) were also included in the ownership of these tunnels in a way that they had a particular quota of revenues generated through individual tunnels. At the same time, Hamas obtained between 25 and 40% of tunnel revenues … Traders tooka dvantage of the significantly cheaper prices of goods smuggled from Egypt … At the same time, goods were sold in the local markets at the same price as Israeli-taxed goods… Hence, new traders were able to make significant profits … The high security risks and security considerations involved …. led Hamas to only allow a smaller group of Hamas-vetted traders …. to get involved … “

At its height in the early 2010s Hamas was likely generating $750 m per year in revenue from the tunnel system. Crucially, the tunnel system enabled a supply of construction materials with which Gaza could meet its need for housing and rebuilding after the disastrous confrontation with Israel in 2008-9. As UNCTAD reports:

… between 2007 and 2013, (there were) more than 1,532 underground tunnels running under the 12 km border between Gaza and Egypt. …. The size of the tunnel trade was greater than the volume of trade through official channels (World Bank, 2014a). According to the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, based on the materials allowed in by Israel, it would have taken 80 years to rebuild the 6,000 housing units destroyed during the military operation in December 2008 January 2009. However, imports through the tunnels were so significant that they reduced the time frame to five years (Pelham, 2011). Similarly, Gaza’s power plant ran on diesel from Egypt brought through the tunnels in the range of 1 million litres per day before June 2013 (OCHA, 2013).5

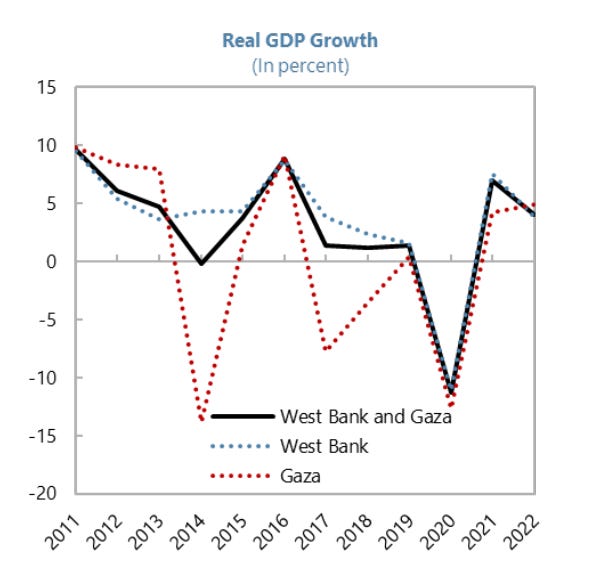

The tunnel economy reached its peak between 2011 and 2013 after Mubarek’s repressive regime in Egypt was overthrown in the Arab spring and the Muslim Brotherhood ruled in Cairo. With supplies flowing in, and the construction sector booming, Gaza’s GDP per capita rebounded from the low of 2008. But then double disaster struck.

In July 2013 the Egyptian military seized power, overthrowing the allies of Hamas, and a year later, in July 2014 Israel launched its 50-day war against Hamas. The result was utter devastation. Not only was Gaza subject to a devastating bombardment by tens of thousands of artillery shells and bombs, but a joint Israeli-Egyptian campaign closed off the tunnel system.

By May 2015 the number of Palestinian refugees solely reliant on food distribution from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) increased to 868,000 by May 2015, representing half the population of Gaza and 65 per cent of the registered refugees (UNRWA, 2015b).

Nor were bombardment and isolation the only threats that the Gazan economy had to deal with. As IMF data, show, the Gazan economy rebounded from the massive shock of 2014, only in 2017 to suffer a financial crisis and government spending squeeze. Tannira summarizes a disastrous escalation of this austerity.

Compounding the financial pressures on the Palestinian authorities, Israel regularly withholds tax revenue which are due under the Paris economic agreements of 1994.

Under the impact of these pressures, even before the current explosion of violence it has become increasingly difficult to speak of Gazan economic development at all. GDP per capita has slumped towards as little as $1500 per capita. The unemployment rate in Gaza hovers between 40 and 50 percent, roughly three times higher than in the West Bank.

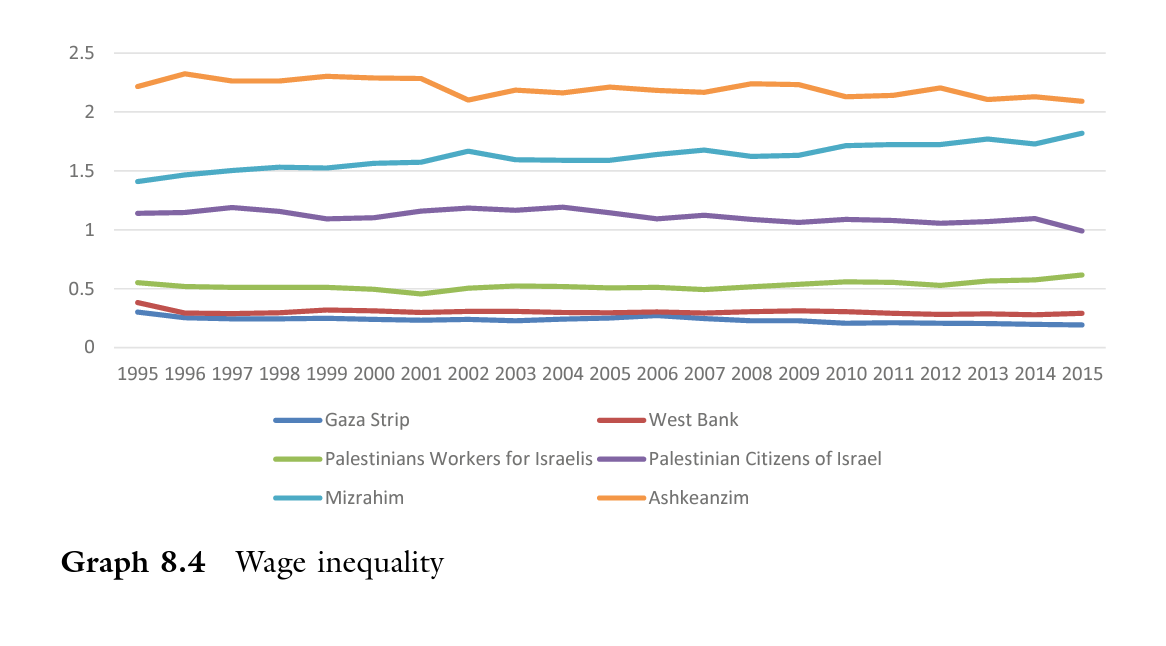

As Shir Hever’s data show, wages in Gaza stagnate at the very bottom of the racialized pyramid in Israel/Palestine.

In the 1980s when Roy first coined the idea of “de-development” her aim was to insist that Gaza was not developing even though incomes were growing. Since 2014 even that seems over-optimistic. The Gaza economy as such has been extinguished. When people speak of an “open-air prison” they barely exaggerate.

III] DISPOSABLE DE-DEVELOPMENT

In the final edition of Roy’s ground-breaking work, which appeared in 2016:

she argues that Gaza’s trajectory over the last 48 years has reconstructed the territory from one that had been economically integrated and deeply dependent upon Israel and strongly tied to the West Bank, to an isolated and disposable enclave cut off from the West Bank as well as Israel and subject to ongoing military attacks.

So, this is the answer to our question. This is how half the population of Gaza can simply be ordered to move from one end of the enclave to the other. The civilians have no wealth to speak of and few or any connections with the outside world. They depend, in any case on aid and what little they can smuggle in. They have become, as Roy so presciently put it, “isolated and disposable”. At this moment of crisis, the IDF would prefer not to have them in the way, when what it wants to concentrate on doing is killing Hamas fighters and destroying their military infrastructure. So it is time for them to move.

You must be logged in to post a comment.