collective on geoeconomics

30/07/2023

I] THE MALAYSIAN ECONOMY

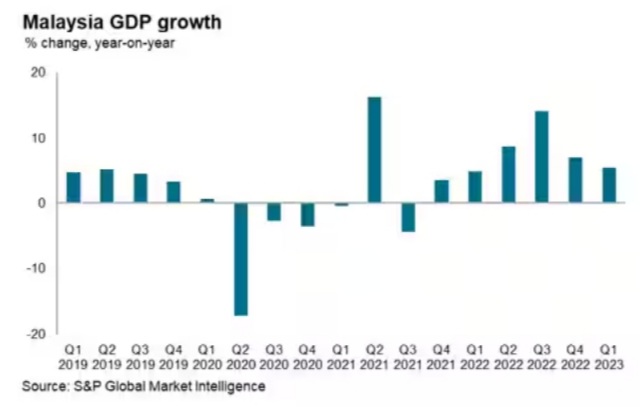

The national economy grew at a bouyant pace of 5.6% year-on-year (y/y) during the first quarter of 2023, indicating a continuous and fast-paced expansion after an annual economic growth rate of 8.7% in 2022 which was the fastest annual GDP growth rate since 2000.

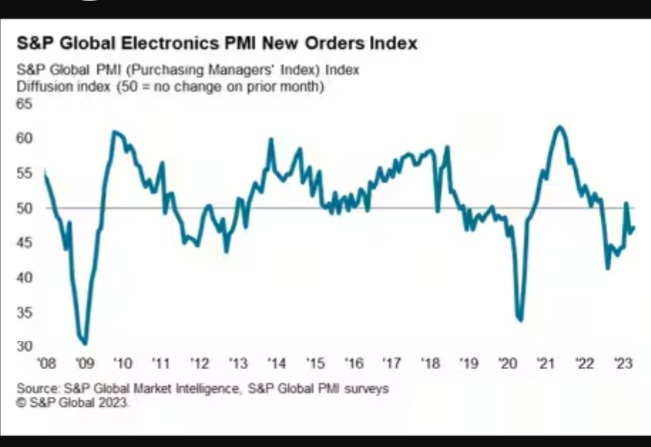

However, the pace of expansion is expected to moderate during 2023 due to a number of geoeconomics headwinds, including the impact of high base year effects and sliding down of merchandise export growth.

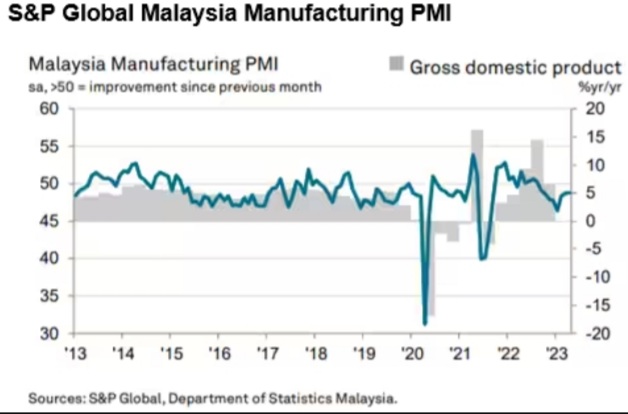

The Malaysian economy is able to maintain a positive momentum during the first quarter of 2023 is due to a strong domestic demand where the services sector continued to show rapid growth of 7.3% y/y in the first quarter of 2023. The pace of expansion in the construction sector also remained strong, growing by 7.4% y/y in the first quarter of 2023. However, growth in the manufacturing sector has moderated in recent quarters, growing by 3.2% y/y in the first quarter of 2023, not dissimilar to the 3.9% y/y pace in the fourth quarter of 2022.

According to the seasonally adjusted S&P Global Malaysia Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) was unchanged at 48.8 in April, indicating that business conditions remained challenging for firms.

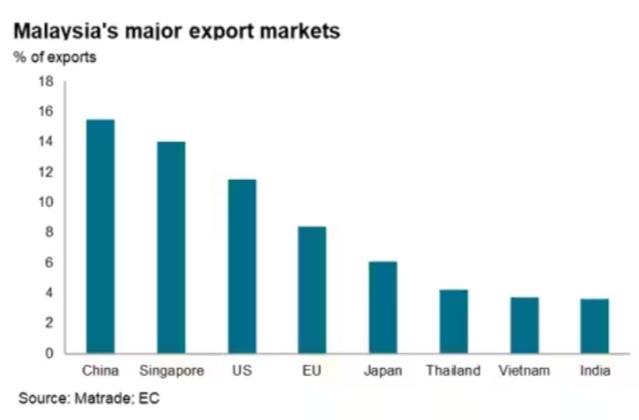

As mainland China is Malaysia’s largest export market, accounting for 15.5% of total exports, the continuing rebound in mainland China’s economy during 2023 may help to mitigate the impact of other softening merchandise exports to the US and EU.

The main products exported from Malaysia to China were Integrated Circuits (US$11.2B), Petroleum Gas (US$3.27B), and Blank Audio Media (US$2.23B). During the last 26 years the exports of Malaysia to China have increased at an annualized rate of 12.2%, from US$2.42B in 1995 to US$47.9B in 2021.

China and Malaysia witnessed frequent and close high-level exchanges in 2022 with bilateral trade between the two countries reaching a record high of US$203.6 billion (US$1=RM4. 42), according to Chinese Ambassador to Malaysia Ouyang Yujing, (MIDA, 17 February 2023).

The IMF July Report 2023 says that under its baseline forecast, growth will slow from last year’s 3.5 percent to 3 percent this year and next – a 0.2 percentage points upgrade for 2023 from its April projections. Global inflation is projected to decline from 8.7 percent last year to 6.8 percent this year – a 0.2 percentage point downward revision, and 5.2 percent in 2024.

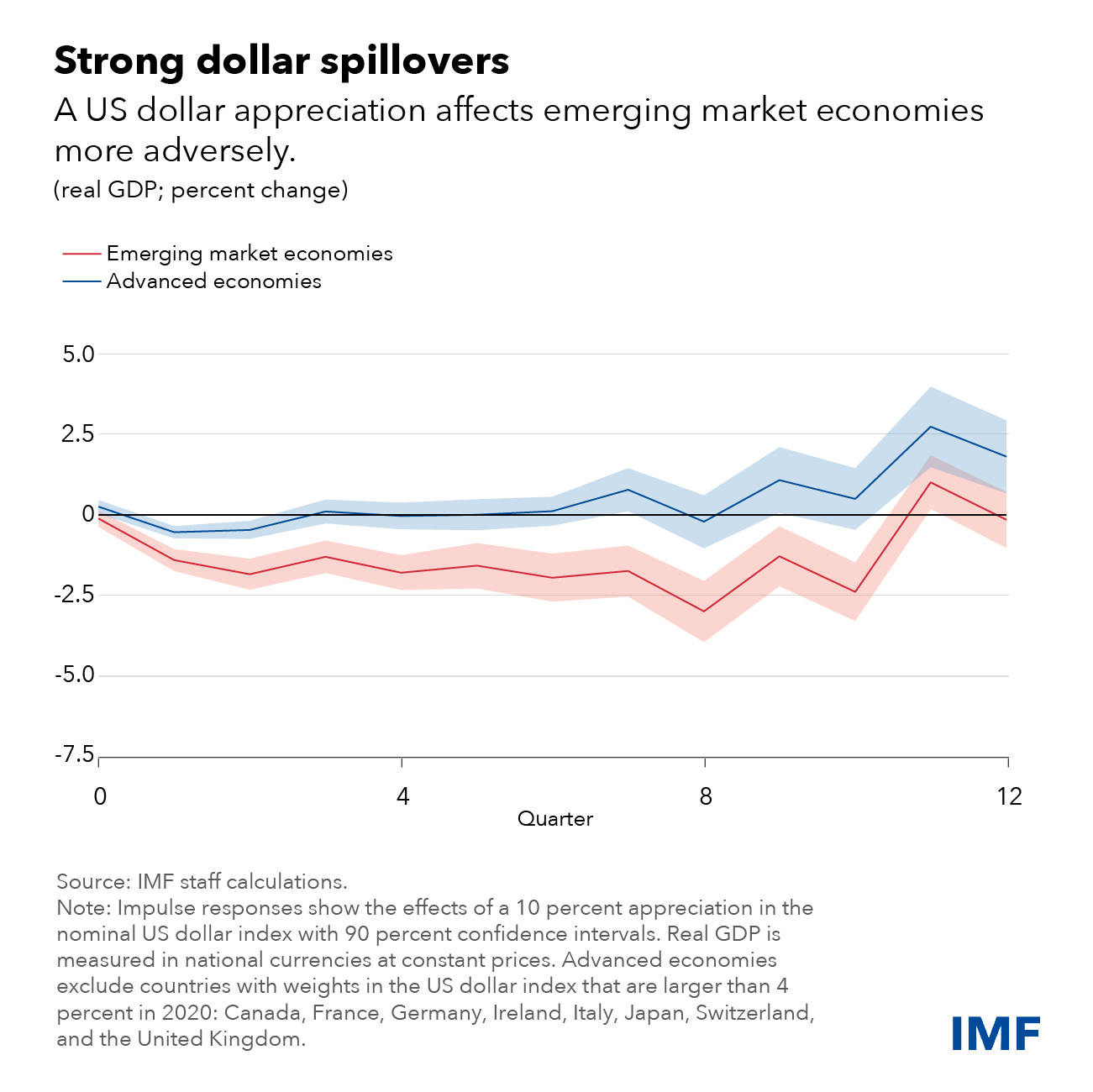

The slowdown is concentrated in the developed economies, where growth will fall from 2.7 percent in 2022 to 1.5 percent this year and remain subdued at 1.4 percent next year. The euro area, still reeling from last year’s sharp spike in gas prices caused by the Ukrainian cross-border special military operation, is set to decelerate sharply.

By contrast, growth in emerging markets and developing economies is still expected to pick-up with year-on-year growth accelerating from 3.1 percent in 2022 to 4.1 percent this year and next.

As our national economic vitality is dependent on China’s economic performance, we shall present the following excerpts from the ASIA TIMES – taking into various assessments and analyses from academic think-tanks, commercial consultants and China-watchers – as to what implications thereon shall affect the MADANI economy praxis and consequential development performance.

II] STATE OF CHINA’S ECONOMY

China’s anti-Mario Draghi moment surprises markets

China is eschewing the former European Central Bank chief’s pledge to ‘do whatever it takes’ to stabilise via monetary easing.

For weeks now, global markets have ricocheted between excitement over a Chinese stimulus boom and disappointment that Beijing was taking its sweet time to jolt a slowing economy.

It’s now clear that Xi Jinping’s team has settled on a strategy somewhere in between. And for the global economy, the signals from this week’s meeting of the Politburo, the Communist Party’s top decision-making body, seem short-term negative for world markets – but long-term positive.

As Bill Bishop, long-time China-watcher and author of the Sinocism newsletter, sees it, the policy direction being telegraphed seems “fairly dovish,” but “doesn’t seem to signal much more significant stimulus incoming near-term.”

That’s bad news for bulls betting on a new Chinese stimulus bonanza that lifts markets from New York to Tokyo. Under the surface, though, there are myriad hints that the arrival of Premier Li Qiang in March is putting reforms on the front-burner once again. In other words, Beijing cares more about avoiding boom/bust cycles going forward than just mindlessly fuelling a 2023 boom.

As “no fiscal expansion plans have been revealed so far, the impact will only be felt very progressively,” says economist Carlos Casanova at Union Bancaire Privée.

Economist Wei He at Gavekal Dragonomics added that “the Politburo’s meeting on the economy shows that officials recognise weak demand is an issue. But the meeting mainly called for ‘precise’ policy adjustments.” As such, it “remains far from certain whether those can deliver a near-term turnaround in growth. The conservative stance points to, at best, a stabilisation or weak recovery” in the second half.

Instead of aggressive plans for massive monetary easing and fiscal pump priming — as markets had assumed — the chatter is about prudent policymaking with an emphasis on lower taxes and fees and incentivising increased investment.

Rather than sharp drops in the yuan to boost exports, Li’s reform squad is focused on catalysing greater scientific and technological innovation and giving the private sector more space to thrive and create new good-paying jobs.

In lieu of scores of top-down decrees or public jobs-creation schemes, the zeitgeist is that developing a thriving micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSME) sector is a more forceful way to address record youth unemployment than large-scale stimulus.

What Xi and Li are telegraphing might be best called the “anti-Mario Draghi” approach to enlivening Asia’s biggest economy.

The reference here is to the former European Central Bank president’s infamous pledge “to do whatever it takes” to stabilise the financial system via powerful monetary easing.

A year later, Draghi’s liquidity onslaught inspired then Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda to follow suit.

On Draghi’s watch, the ECB unleashed stimulus on a level that would’ve been unfathomable to Bundesbank officials of old. In Tokyo, between 2013 and 2018, the Kuroda BOJ’s balance sheet swelled to the point where it topped the size of Japan’s $5 trillion economy.

Neither monetary boom did much, if anything, to make the broader European or Japanese economies more competitive, productive or, broadly speaking, more prosperous. Instead, executive monetary support generated a bubble in complacency.

Draghinomics — and Kurodanomics — took the onus off government officials from Madrid to Seoul to loosen labor markets, reduce bureaucracy, incentivise innovation, tighten corporate governance or invest big in strengthening human capital.

China, it seems, is determined to go the other way. In the months since Xi started his third term — and Li arrived on the scene as his number two — Beijing has confounded the conventional wisdom on Chinese stimulus.

The start of this week’s Politburo is no exception. Markets were betting on major stimulus moves. Instead, China unveiled a 17-point plan to attract more private capital its way.

In a note to clients, analysts at Capital Economics said that “the absence of any major announcements of policy specifics does suggest a lack of urgency or that policymakers are struggling to come up with suitable measures to shore up growth.”

One possible interpretation was that Xi’s inner circle wants to put some actions on the scoreboard before next month’s annual huddle in the resort of Beidaihe to discuss long-term policy direction. Yet the tenor of steps seems more about supply-side reforms than fiscal and monetary pump-priming that might squander progress in reducing financial leverage.

Instead of talking about reaching this year’s 5% growth target, the government said the priority now is that “good foundation is laid for achieving the annual economic and social development targets.” Officials admitted, too, that “economic recovery will show a wavy pattern and there will be bumps during progress.”

In other words, the instant gross domestic product gratification that investors came to expect in Xi’s first two terms has been replaced with a more pragmatic approach. While there will be “prudent monetary policy” and at times an “active fiscal policy,” the bigger objective is to “extend, optimise, improve and enforce tax cuts and fee reductions.”

Stimulus will indeed emerge when, and where, needed. The Politburo said, for example, that it would “accelerate the issuance and use of local government special bonds.”

This means it’s entirely possible that local governments may be allowed to “dig into” remaining special bond quotas, including from previous years, says economist Yu Xiangrong at Citigroup, who estimates the quota to be about 1.1 trillion yuan (US$154 billion).

But there was far more discussion of ways to “adapt to the major change in supply-demand relations in the property market,” and, in timely fashion, to “adjust and optimise real estate policies.”

That, Beijing says, means steps to “increase construction and supply of low-income housing,” and “revitalise all types of idling properties.”

To economist Zhiwei Zhang at Pinpoint Asset Management, “this is an interesting signal as the property sector downturn is arguably the key challenge the economy faces now.” As such, “it seems the government has recognised the importance of policy change in this sector to stabilise the economy.”

Just as important, arguably, is the government saying it’s committed to “effectively prevent and resolve local debt risks, make a package of plans to resolve the debt.” The same goes for commitments to “concretely optimise private firms’ development environment” and “build and improve the routinised communication mechanism with companies.”

Furthermore, the party’s latest phraseology includes pledges to “firmly crack down on excess fee and fine charging, resolve the receivables governments owe to companies” and “accelerate the fostering and growing of strategic emerging industries.” The plan, the party notes, is to “strengthen financial regulation, steadily push for the reform and risk resolution at small and medium-sized financial institutions of high risks” as a means to “stabilise the basic market of foreign trade and investment.”

Such language is more the stuff of Adam Smith and Milton Friedman than Mao Zedong. More Hans Tietmeyer of Bundesbank fame than Draghi or Kuroda. One possible area of optimism is that Xi’s government is finally serious about fixing the underlying troubles in the property sector – not just treating the symptoms.

Casanova points to the Politburo’s statement that authorities would recalibrate property policies based on the “local property market situation” and consider developments related to “demand and supply imbalances.” To him, “that last point is new, suggesting a change in the macroprudential regime, as the government now sees a structural shift, requiring bottom-up measures to better reflect local conditions.”

That’s not to say Xi and Li won’t support demand where needed.

“We expect the government to roll out modest fiscal support in the second half of 2023, but no aggressive fiscal stimulus,” says economist Ning Zhang at UBS AG. Even so, Zhang says, “some policy room may be kept to support economic growth in 2024.”

Additional stimulus measures that Zhang expects Beijing to prioritise: an acceleration of special local government bond sales; a resumption of policy banks’ special infrastructure investment funds; Beijing providing credit to clear up local governments’ arrears to corporate suppliers; modest property policy easing and credit support for stalled property projects; a modest credit growth rebound; and perhaps a small official rate cut.

There also could be “some small-scale and targeted support” for selected consumption categories as well, Zhang says.

Mostly, though, the signals coming from Beijing this week suggest a greater emphasis in increasing confidence via reform and more vibrant safety nets than runaway stimulus. Bottom line, China’s Draghi days seem over – and that’s a good thing.

first published: ASIA TIMES July 26, 2023.

III] IMPLICATIONS

Just as there shall be a subdued growth path in China, but with targeted support and selective structural changes, the unity government in Malaysia will pump in more than RM$5 billion to kick off its Madani Economy Framework to enhance the economy and improve national competitiveness.

- The framework has lofty ambitions of positioning Malaysia as one of the top 30 major economies around the globe within 10 years,

- Placing the country in the top 12 of the Global Competitiveness Index,

- Increasing participation among women in the country’s workforce to 60 per cent,

- Placing the country in the top 25 nations in the world in the Corruption Perception Index,

- Boosting the nation’s fiscal strength with fiscal deficit of three per cent or lower, and

- Positioning Malaysia in the top 25 of the Human Development Index,

- Additional allocation of RM400 million for micro financing under SME Corporation Malaysia, National Entrepreneurial Group Economic Fund’s (Tekun), Majlis Amanah Rakyat (MARA) and Bumiputera Agenda Steering Unit (Teraju). This fund is aimed at providing entreprenuerial opportunities, trainings and financing for the marginal groups including women and youth,

- Another new major funding assistance announced under Madani Economy Framework is a financing worth RM$200 million under Agrobank to facilitate the application of technology in farming,

- The country could record a six per cent growth if everyone “initiates change”.

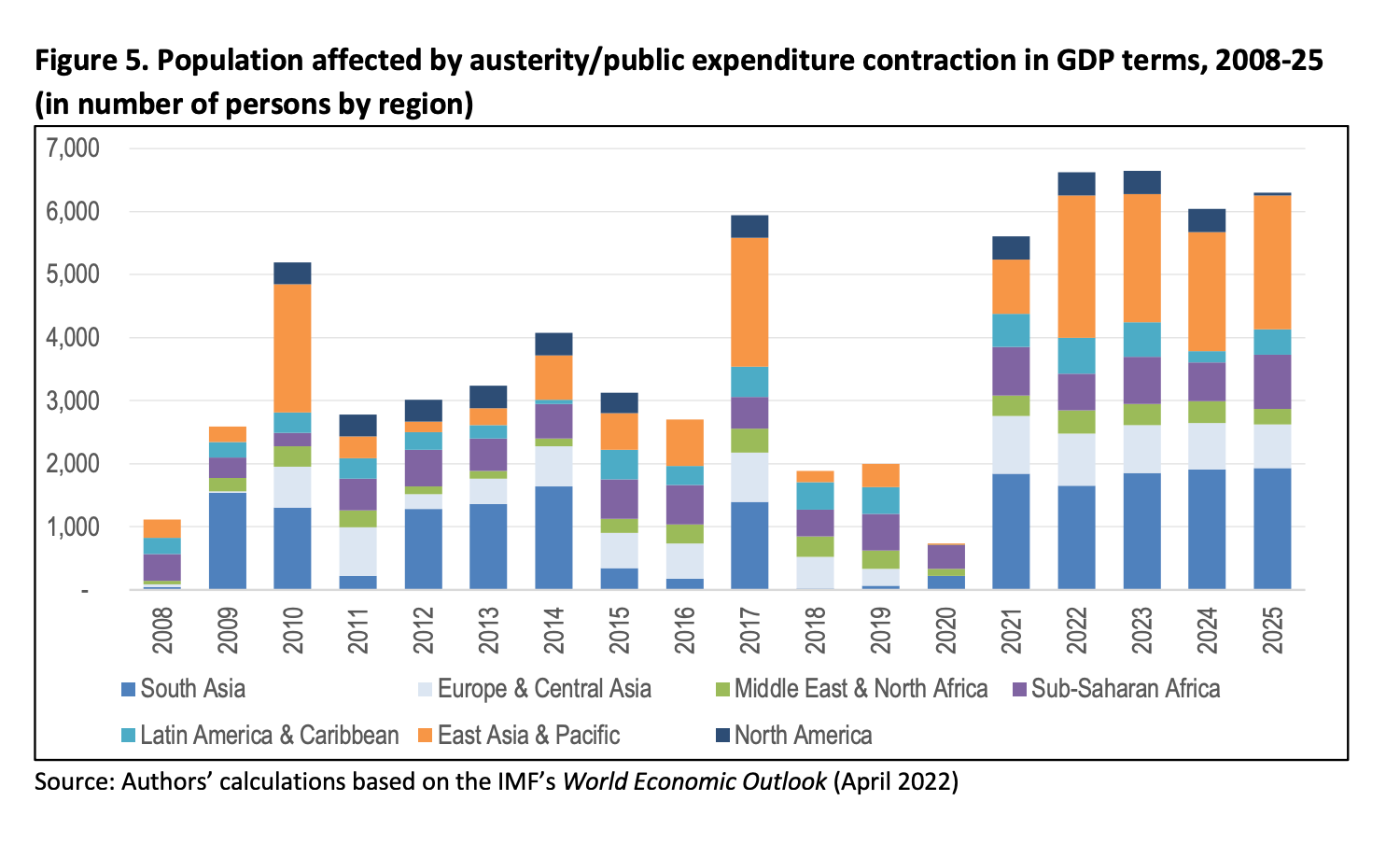

- The successful reaching of targeted area poverty alleviation objectives (TAPAO) will thus dependent on the genre of structural changes to be adopted, the availability of debt financing in economic development, the wholeheartedly adherence to sound economic developmental praxis and a faithfulness to the core MADANI implementation principles.

Then, only thence, shall the country shares a common wealth destiny with our rakyat².