Collective on Geoeconomics

24/04/24

PREAMBLE

First it was that since the U.S. cannot outcompete China, then it is not by accelerating the growth of U.S. economy but by slowing China’s.

As the U.S. could not suffocate that civilisational state in Asia, therefore, the hegemon in a Hyper-Imperialism state has to persuade China to commit an economic suicide, (John Ross, monthlyreview 20/04/24).

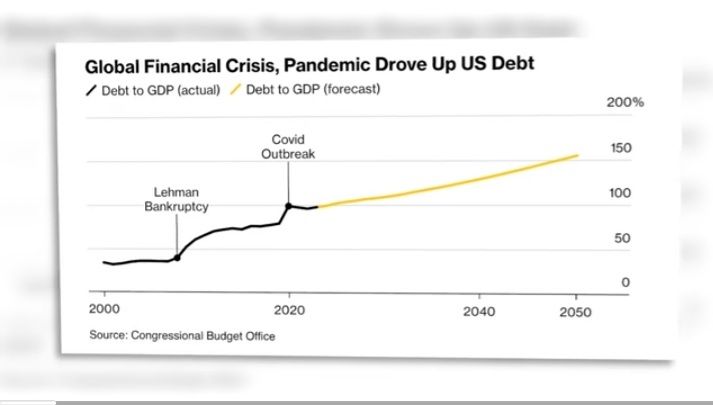

However, instead of devoting more attention to domestic economics in U.S., this global war machine is building military bases in a hegemonic hubris straining under multilateralism as a rogue’s in itself – and contributing to global growth problems – by disinvestment compared to China state enterprises, (see detailed exploration and elaboration in STORM April 2023), inevitably inducing China’s better socio-economic performance compared to the collapse of American capitalism with an increasing accompanying national debt crisis.

Now, unable to compete efficiently with China, the U.S. geo-political economics praxis is destabilising world economy through deglobalisation the supply chain especially with China‘s manufacturing prowess with a socialism efficiency economic development model , and to promote an alternative news campaign about China’s overcapacity as part of peaked China narrative, (John Ross, May 2023).

Here, from the pages of Philippa Jones of CHINA POLICY – a Beijing-based research and advisory company responding to China’s changing domestic policy and its geopolitical impact – we continue with

Beijing debates overcapacity

The diverging perspectives among well-known commentators Huang Yiping 黄益平 and Lù Fēng 路风 (to distinguish him from Lú Fēng 卢锋, who, just to confuse us all, also contributes to the debate). They are all colleagues at the same famously radical university.

From a campus nearby, Sun Liping 孙立平 posits that the current overcapacity prefigures the end of a ruling paradigm. It reminded me of his analysis just after the lockdowns. Our brief from 2023 ‘post lockdown realities’ highlighted Sun (one of the PRC’s economically savvy, bellwether intellectuals) and his brilliant ‘neo-dual structure’, along with his incisive diagram explaining it… a year on his theory is more convincing than ever.

The New Era sees new postures towards excess capacity

Long circulating in the media, overcapacity has become the hot-button issue in the PRC–West disaffection. US Commerce Secretary Janet Yellen’s early April 2024 visit to the PRC largely centred on it. In a meeting with German Chancellor Scholz on 16 April 2024, General Secretary Xi told Scholz that both sides should address production capacity ‘objectively’.

Yellen proposed formalising dialogue on excess industrial capacity in EVs (electric vehicles), solar panels and batteries, warning the US would not accept the ‘decimation’ of its industry. The PRC, she insisted, is simply too large to export its way to growth.

The US is not alone in its concerns. An EU probe into the PRC’s trade practices in EVs opened in EVs opened in October 2023; another, centred on wind turbines, started in April 2024. The bloc would later that month update and expand a list of sectors potentially distorted by PRC measures, including key strategic emerging industries like semiconductors and renewable energy products, opening the door for more anti-dumping investigations.

Excess capacity has been characteristic of the PRC economy for decades. Given its move up the value-added chain, excess capacity becomes a nagging geopolitical topic. The issue is Beijing’s ability/desire to do something about it.

Beijing’s supply side

Beijing’s understanding of the ‘supply side’ clearly differs from that of mature economies. As Xi explained the ‘new development paradigm’ to a February 2023 Politburo study session, Beijing seeks to improve demand’s efficacy in guiding supply while seeing higher-quality supply drive demand. Overcapacity might then pose problems but would eventually solve itself, given ideal central policymaking.

Conflicting views on overcapacity pervade the PRC leadership. Addressing domestic audiences, the centre rails against overcapacity. It was identified as a top problem in certain sectors in both December 2023’s CEWC (Central Economic Work Conference) and the 2024 Government Work Report. Specific sectors were not identified. CEWC 2023’s economic agenda featured supply-side structural reform, a cause first flagged back in the early 2010s, when a major increase in overcapacity was last faced.

Faced with overcapacity as a part of broader rivalry with the West, officialdom strikes a different tone. Wang Wentao 王文涛 Minister of Commerce dismisses charges of overcapacity in EVs: advantage comes not from subsidies but from PRC firms’ constant innovation and supply chain improvement.

The overcapacity debate is deemed another case of the US damaging regular trade in the name of national security, explains Liao Min 廖岷 a deputy finance minister. Overcapacity simply demonstrates the price mechanism at work: prices fall as supply outstrips demand. Both should soon readjust.

Global markets must be considered. Demand for solar panels is forecast to quadruple by 2030, far beyond what current capacity can supply. The PRC simply fulfils domestic demand while contributing to the international green transition.

Overcapacity is overhyped, editorialises Xinhua. Developed states routinely seek markets for goods in which they have advantages, yet when the PRC does the same, it is deemed disruptive. Put simply, the West fears losing its monopoly position in the global division of labour and the wealth it brings. Proclaimed ‘decoupling’ is meant to subdue latecomers like the PRC, add Xinhua.

cyclical conditions

More sectors are reaching overcapacity (defined as production exceeding demand and rational output levels), estimates Lú Fēng 卢锋 Peking University National Development Institute, including

petrochemical raw materials

automobiles

above all gas-powered

batteries

microchips

NEVs (new energy vehicles)

The PRC has undergone three waves of overcapacity since reform and opening, reckons Liang Yongmei 梁泳梅 CASS Institute of Industrial Economics. These were of

- consumer goods during the late 1990s;

- certain industrial goods in some firms (particularly cement, steel and aluminium) from 2003 to 2007;

- generalised and including a wider range of industrial goods from 2010 to 2016

These cycles were closely linked to global economic performance: as demand falls, capacity utilisation drops due to falling orders and mounting stocks. But that fails to account for their stubborn recurrence. Constant PRC industry upgrades repeatedly generate swathes of old capacity, under certain circumstances deemed ‘over’. Worsening the problem, local governments routinely help firms boost capacity to consolidate the tax base and create jobs. Overcapacity keeps showing its ugly head. Capacity utilisation in high-tech goods is for the first time falling faster than in conventional industry, laments Wu Ge 伍戈 Changjiang Securities. Even an industry leader like batteries giant CATL reaches only 70 percent capacity utilisation.

The PRC morphed from a society facing chronic scarcity to one with constant overcapacity in 1997, explains critical sociologist Sun Liping 孙立平, due to its investment-led growth model. The current manifestation may be the end of the road. Solving overcapacity is no easy matter of increasing demand. This is true of consumption above all. Investment-led growth is the raison d’etre of institutions like banks, the fiscal state and equities markets. Reforming them is intractable yet a prerequisite to solving overcapacity, as Sun cogently shows.

growing debate

As Beijing refines its narrative, domestic debate on overcapacity grows in the gaps. Different this time, explains Lú Fēng 卢锋, is the spread of overcapacity to high-end emerging industries, not least those with lucrative global markets. Given the lack of global mechanisms to coordinate (over)capacity, industry consolidation and increased exports are to be expected.

Take care in such moments, warns Huang Yiping 黄益平 Peking University National School of Development. Developing new productive forces will entail maintaining openness with other countries, not least advanced economies. Now massive, the PRC economy can no longer export its excess capacity without punitive blowback. Policy must focus on innovation, not capacity, maintaining good relations while advancing modernisation.

Demurring, Lù Fēng 路风 Peking University School of Government (note different name) contends supply-side structural reform has cramped growth over the past decade. More industrial production is always good, driving demand for intermediate goods in a virtuous cycle essential for development. Focusing only on ‘strategic emerging’ or future industries dooms the economy to stagnation. Overcapacity concerns are, hence, misplaced at best and fatal at worst.

a dangerous moment

Adding critically to the danger, explains Sun Liping, is reentry to overcapacity, just as the world does likewise. Decoupling and reshoring efforts have generated massive investment in manufacturing in all major economies, including the US, Europe and Japan. Trade wars and protectionism now seem unavoidable.

Beijing reacts as if cornered. In early April 2024, Xi told US President Biden he would not stand by as the US kept suppressing PRC initiatives to advance its technology and economy. Measures designed to penalise overcapacity in those terms are easily grasped–irresistibly so in Beijing. Accepted as a problem, the ominous geopolitical shadow cast by overcapacity may force Beijing to alter its posture.

profiles

Huang Yiping 黄益平 | Peking University National School of Development president

For Huang, nurturing new productive forces entails maintaining openness, above all with advanced countries. Tech exchange supports total factor productivity, a hallmark of new productive forces and blessed by Xi.

Overcapacity again becomes controversial because the PRC fails to handle its causes: frequent imbalance between investment and consumption, coupled with (state-led) excessive resource allocation to certain sectors. The PRC economy’s sheer scale is new. Domestic supply and demand lose relevance: domestic changes directly impact global markets in ways that other export-oriented developmentalist states were able to avoid.

To avoid conflict, industrial policy should focus on innovation rather than capacity, with strict adherence to multilateral fora like the G20 and rebalancing the economy towards consumption.

Holding an economics PhD from the Australian National University, macro policy heavyweight Huang divides his working life between scholarship, the private sector and government. His experience includes Columbia University, CitiGroup, Caixin Media Group, PBoC’s monetary policy committee and the China Finance 40 Forum. He replaced Yao Yang 姚洋 as head of Peking University’s National School of Development in early 2024.

Lu Feng 路风 | Peking University School of Government

Obliquely challenging the pressure to de-capacitise, Lu insists overcapacity is overhyped, a manifestation of anxiety about rivalry with US economic power. Supply-side structural reform has indeed cramped development over the past decade. Becoming wealthier and raising living standards entails producing more, regardless of demand from moment to moment.

Take steel as an example, says Lu: production was capped centrally in 2016. Yet, a bare decade later, domestic demand far exceeds the cap: those limits were, this implies, pointless in the first place.

Feng warns that the focus on innovation must not be too narrow. Intermediate goods must indeed have greater scale than strategic emerging industries: their economic contribution is not to be underrated. Large traditional industries are needed to create vaunted ‘future industries’: new tech applications emerge only when experts in existing sectors create them.

After graduating from China Minzu (’Minorities’) University in 1982, Lu worked in state agencies. He took a PhD in Political Science from Columbia University from 1991 to 1998 and completed a postdoc at Berkeley. He returned to teach at Tsinghua University in 1999. He later directed the Enterprise and Government Research Institute in the School of Public Management, moving to Peking University in 2003.

Sun Liping 孙立平 | Tsinghua University Department of Sociology professorThe era of large-scale concentrated consumption experienced previously is basically over, said Sun in a speech on 14 April 2024. The PRC economy is in a period of contraction, and the consumer sector too is at a turning point. In conventional consumption’s current stage of gradually dividing, he said, ‘the poor cannot afford, the middle class does not dare, and the rich do not know what to consume’ has become a common impression. Given differentiating consumption, and the background of economic contraction, consumption of society as a whole faces a downward trend. Overcapacity is just a manifestation of this reality.Born in a Hebei village in 1959, Sun studied journalism at Peking University 1978–81, taking up sociology at Nankai University 1981–83. A journalist for some years, he joined Tsinghua University in 1993. He famously helped advise a younger Xi Jinping’s PhD dissertation, the resulting political capital arguably allowing him to test the limits of intellectual expression. His bestselling 1996 book, The Road to Modernisation, argued that politics had been outpaced by economic growth, brewing corruption, inequity, and unrest. With over 300 other intellectuals, Sun co-signed the ‘Charter 08’ open letter to the Party, urging political reform. He warned Caijing Magazine’s annual Forecasting and Strategy conference in 2013 of a ‘crisis of legitimacy.’ Widely reported, this caused a stir. Other notable works include Social Reconstruction (2009), China’s Political Reform (2011), and Crisis of Legitimacy (2013).

Sun Liping 孙立平 | Tsinghua University Department of Sociology professorThe era of large-scale concentrated consumption experienced previously is basically over, said Sun in a speech on 14 April 2024. The PRC economy is in a period of contraction, and the consumer sector too is at a turning point. In conventional consumption’s current stage of gradually dividing, he said, ‘the poor cannot afford, the middle class does not dare, and the rich do not know what to consume’ has become a common impression. Given differentiating consumption, and the background of economic contraction, consumption of society as a whole faces a downward trend. Overcapacity is just a manifestation of this reality.Born in a Hebei village in 1959, Sun studied journalism at Peking University 1978–81, taking up sociology at Nankai University 1981–83. A journalist for some years, he joined Tsinghua University in 1993. He famously helped advise a younger Xi Jinping’s PhD dissertation, the resulting political capital arguably allowing him to test the limits of intellectual expression. His bestselling 1996 book, The Road to Modernisation, argued that politics had been outpaced by economic growth, brewing corruption, inequity, and unrest. With over 300 other intellectuals, Sun co-signed the ‘Charter 08’ open letter to the Party, urging political reform. He warned Caijing Magazine’s annual Forecasting and Strategy conference in 2013 of a ‘crisis of legitimacy.’ Widely reported, this caused a stir. Other notable works include Social Reconstruction (2009), China’s Political Reform (2011), and Crisis of Legitimacy (2013).

RELATED REFERENCES