PROLOGUE

Malaysia is at a crossroad in its politico-economic path with fractious politics and a contracting middle class. The socio-economic conditions are becoming precarious. This is because of a stagflation risk arising amid sharp slowdown in growth that is accompanied by an accelerated inflation runaway globally, (World Bank, Global Economic Prospects, June 7, 2022); this is confirmed by the Bank of International Settlements in its Annual Economic Report, 26 June 2022; Prof. Adam Tooze‘s detailed write-up in Chartbook# 131.

In 2020, the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) indicated that there were almost four million people working in the gig economy in Malaysia; independent think-tank, Emir Research, confirmed about 26% of the Malaysian labour

force were full-time gig workers, reaching 30% by 2021.

1 BIG TECH

Tech capital flows unencumbered trans-borders where new ecosystem of digital platforms has emerged over the past decade that is transforming the very infrastructures of capitalism. This new business model of large monopolistic digital platforms are capable of extracting immense amounts of data overwhelming legacy enterprises and suppressing labour empowerment, (Paul Langley and Andrew Leyshon, 2020). This is “netarchical capitalism” , where infrastructure is “in the hands of centralized privately owned platforms”, (Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism, 2017).

Information and infrastructural platforms have empowered a new kind of ruling class. Through the ownership and control of information, this emergent class dominates not only labour but capital. It is not just tech companies like Amazon and Google; even Walmart and Nike can now dominate the entire production chain through the ownership of brands, patents, copyrights, and logistical systems – all “soft” elements than physical end-products, all accumulated through financialization capitalism through a neo-imperialism monopoly-capital pathway.

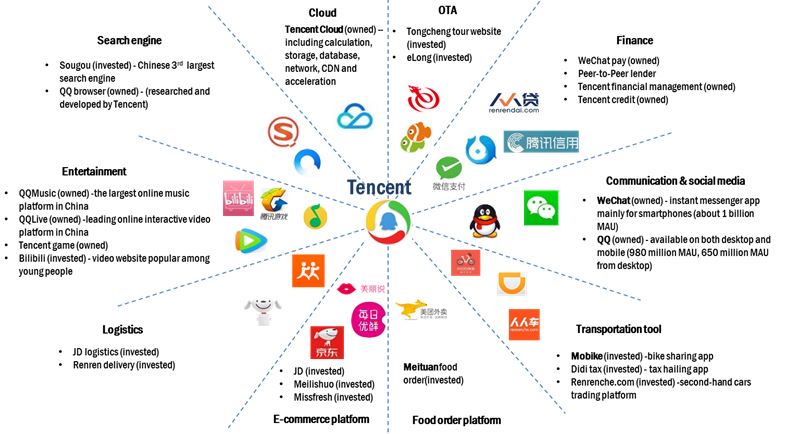

Digital technology has already indeed transformed the world economy; the decade leading up to 2019, the largest 100 firms in the world had increased their total market capitalisation by US$12.7 trillion. A third of that increase (US$4.2 trillion) can be accounted for by just seven firms: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft (the famous quintet ‘FAAAM’), Tencent and Alibaba. The aggressive rally of tech stocks during the COVID-19 pandemic had given due recognition that an entirely new model of value creation was enabled, and primarily all enhanced, by digital technology.

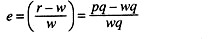

This new ruling class extracts the content capacity of information to route around worker and social movements to barricade labour participation and involvement. The emerging ruling class is the digital feudal lords overseeing a common of digital infrastructure where bands of peasantry-labour are the digital gig-slaves to be exploited. In this digitalized business model, returns do not diminish as businesses scale up but increase exponentially. Geared towards the exploitation of digital-dehumanised workers where they are mere interfacing intermediary conduits to big data storage and retrieval by infrastructural platforms that are so overwhelmingly powerful in exploiting surplus value of labour relentlessly, and with brutal efficiency, it is the accumulation of capital, through and thoroughly (Ursula Huws, Labor in the Global Digital Economy: The Cybertariat Comes of Age, 2014).

To compound developmental efforts, TNCs exploit legal loopholes in low-income countries (LICs) to avoid or minimize tax liabilities by applying a practice known as ‘base erosion and profit shifting’ (BEPS). Under such circumstances, tax havens collectively cost governments US$500–600B yearly in lost revenue. Low-income countries will lose some US$200B – more than even the foreign aids of US$150B that they received annually, (Jomo, June 2022). Indeed, TNCs-supported agents, and lobbies, have blocked the International Tax Cooperation initiative, (Anis Chowdhury and Jomo Sundaram, June 2021) to ensure tax equity and revenue intake equality.

2 GIG LABOUR

Nested in the platform capitalism model is the software component and the associated IT infrastructural platforms’ solutions. Unlike in the manufacturing sector where labour is kept within borders while capital moves freely, in Big Tech there is this process ability to intrude into a target country to install infrastructural platforms as well as troll the planet for cheap labour in any part of mother Earth at any time.

Corporate capital having solidified respective infrastructural platforms which are acquired through IT/IS competitive endowment, now have undue advantages over labour: labour control and supervision, labour harvest and deployment, labour usage and exploitation thereon. Labour, as digital-dehumanised workers, has to process raw data into timely, accurate, relevant and complete information under the control of these infrastructural capitalism platforms.

The resultant, and a transformed economy, is the gig economy, also widely defined as “platform economy”, “on-demand economy” or “sharing economy”, synchronises to the demand and supply of short-term or task-based work activities, and as a part of the national economy where freelancing workers use digital platforms to participate in the national economy, including their connections with the traditional yet formal businesses.

This business model is what technology expert Azeem Azhar names as the ‘AI lock in loop’ where, as the tech companies deploy products and services, they also collect data about their consumers’ use of those products and services. Through machine-learning processes performed on those collated data, these business entities envisage in presenting opportunities towards the development of better products and services. It is by integration of multiple data-rich digital assets into a single platform that gives such tech companies access to the entire vertical product chains (examples like Google or Grab siphoning off personal biodata and geographical locations) and the supply-chain capacity to expand horizontally into new products and services with relative ease and effectiveness. For examples: Google, Facebook, WeChat or Grab becoming cloud-servers, WhatsApp communications and Instagram media aggregator), (Social Europe, Gig Workers Guinea Pigs of the New World of Work, February, 2021; Foundation for European Progressive Studies, Governing Online Gatekeepers: Taking Power Seriously, 2021; see also ILO 2021 report on the states of precarious digital labour).

However, with jobs becoming more and more precarious in a post-pandemic economic recovery phase (see STORM, Capitalism: Crisis to Crisis) and there is this stagnant category of the reserve army of labour or relative surplus population – characterized by low and static wages, low hours, and unregulated, unstable working conditions – are becomong realities in the gig-labour environment (Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1 [Penguin, 1976], 796–98).

Since the new platforms are monopolies that are created by venture/finance capital – the same ones that helped Google, Amazon and Facebook to build their initial monopolies – which helps to enclose the informal sphere of the economy. Uber and Airbnb convert individual vehicle and house owners to what they believe as independent contractors, but in reality are glorified yet untitled serfs! This semblance of a ‘sharing economy’ is, in reality, the enclosure of personal property by digital monopolies and creating new forms of casual labour.

Monopoly-capital radiates to Global South in search of low unit labour costs worlwide to get higher profit margins whilst attaining overall profits. Data on unit labour costs show that countries with the highest participation in labour-value chains – the top three being China, India, and Indonesia – also have very low unit labour costs, (Intan Suwandi, 2019). The neo-imperialism economics is still relevant in today’s digital economy with the generation of, and by, “soft” intellectual elements, but higher, and with the immediate instancy of capital accumulation. That the wealthiest figures in the world today are tech capitalists are unsurprising. The top nine wealthiest people include : Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Page, Pony Ma and Jack Ma (not related to each other). Their excessive wealth points to the tensions within private ownership of the means of production, where competition leads to monopolies and oligopolies. The infrastructural platforms have indeed became double-sided monopolies, a monopoly to their suppliers and monopoly to their buyers, for examples, Alibaba and Amazon not only holds inventories in their warehouses, but also sells goods that it does not store.

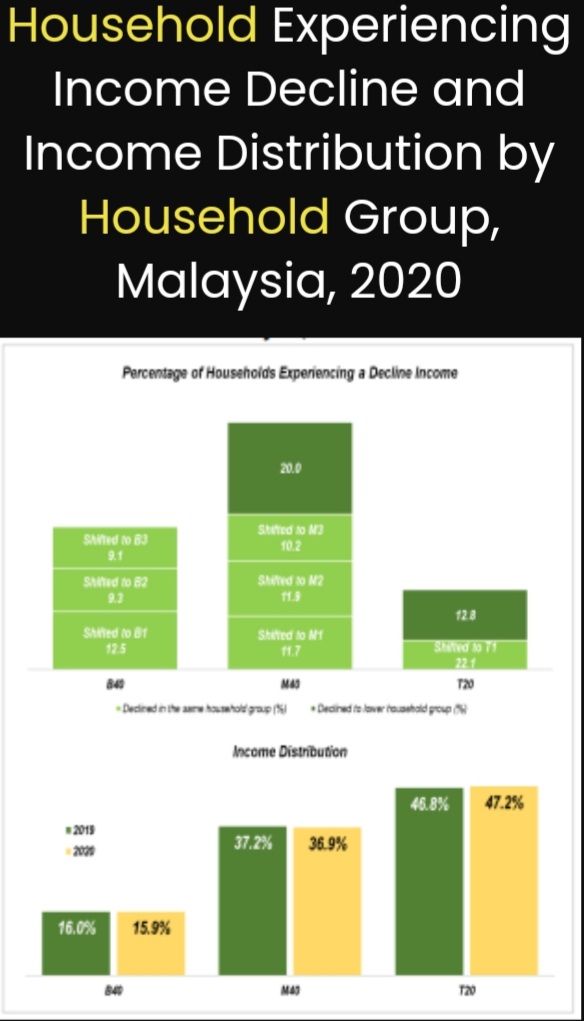

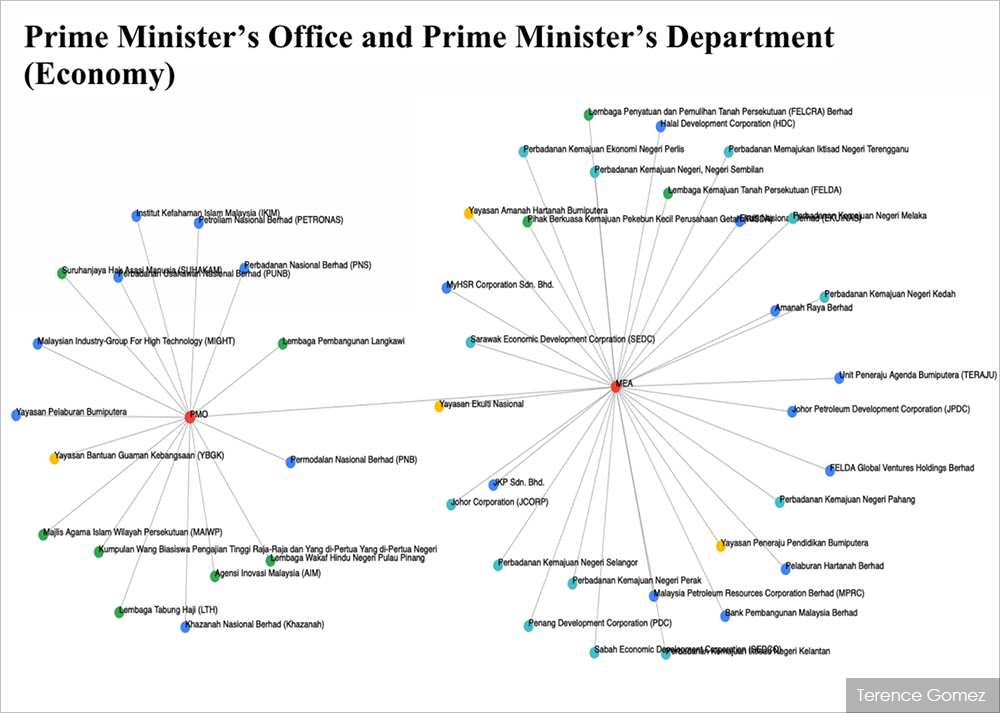

Then we have the Jeff Bezos Amazon factor where The Bezos’ rate is equivalent to US$149,353 a minute. To put things in perspective, Bezos makes more than three times what the median U.S. worker makes in year – US$45,552, according to data by the Bureau of Labour Statistics – in one minute, source: Business Insider 2019. Comparatively, at the centre of an Ecological-Epidemiological-Economic crisis, five captains of the corporate capital became the new millionaires in the country with 2020 ending while the income inequality in Malaysia continues to widen, see Khalid, lse.blog 2019).

Additional in the context of a capitalistic innovation-driven economy, Huws has also expressed her observation where “extraordinary ability of capitalism to survive through the centuries and generate newer commodities by redesigning the nature of work and labor, (Ursula Huws, Labor in the Global Digital Economy: The Cybertariat Comes of Age, 2014).

3 INFRASTRUCTURAL PLATFORMS CAPITALISM FOUNDATION

Large internet firms like Microsoft and Google outsource software development to IT service providers in India, such as Infosys, Cognizant and Wipro. Facebook, similarly, offloads whatever they can’t automate to customer service workers and content moderators, most of whom are based in English-speaking countries in the Global South, (JS Tan, 2021).

Indeed, the global network of tech capital is much larger than these tech giants themselves. The ride-hail industry, for example, is a good case study of how the venture-capital penetrares the Global South. The Japanese Softbank venture capital firm has controls stakes in Uber, Didi (China), Ola (India), and Grab (South-East Asia). Uber itself owns 28% of Grab and 12% of Didi. This means that the exploitation of drivers in China and South-East Asia (where Grab is the dominant ride-hail service) directly contributes to Uber’s bottom line. It is pertinent to acknowledge the struggle against Big Tech, US tech labour organizers should remember that US tech companies have built their fortunes off the exploitation of workers abroad, just as once the Roosevelt families built Boston on the maze of opium farms in India to daze Chinese smokers, (New York Times, 28 June 1997).

Platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk can directly send work to anyone who has a laptop and an internet connection. Ride-hailing and delivery companies like Uber can onboard drivers around the world so long as the drivers have a car and a smartphone. With software development platforms increasingly standardized and accessible from anywhere in the world, even software engineering work has become easy to send overseas. On top of that, the tech industry has also benefited from outsourcing more traditional roles, such as Tesla’s new gigafactory in China, or in customer service work that is routinely outsourced to low-income English-speaking countries like the Philippines or India, (Tan, ibid).

In a contest over international labour arbitrage to stay competitive on the global stage, some American tech workers are forced to accept lower wages or risk losing their jobs entirely. After 80 Pittsburg-based Google contractors, employed by the contracting firm HCL, won their union in 2020, the company began to move work to a branch in Poland, discouraging their workers from further engaging in union activity, (theregister, 9 October 2020).

All the above case-country scenarios are accentuated by a Tech Cold War within a milieu of proxy warefare, (see ECONOMIC CONNECTIVITY IN GEOECONOMICS and Institut Francais des Relations Internationales, Geoeconomics and the Balance of Power in East Asia; newleftmalaysia, The Ukraine Conflict. For instance, TikTok is owned by China’s ByteDance. This video-sharing app has eclipsed Twitter, Facebook and Instagram in the number of downloads in 2020, making it the first major international social media platform that was not developed in the US. The Chinese telecom firm Huawei broke into the international market, which has been otherwise dominated by the US, becoming a major provider of smartphones and telecom infrastructure around the world. These advances have pushed the US government to recoil into a nationalist posture under the Trump administration. Even under the Biden POTUS, and US Indo-Pacific Basin Strategy, there is an intensification of policies that seek to undermine the growth of the Chinese tech sector. However, this nationalist posture has affected some US companies.

In an instance, Google has been reprimanded by politicians for terminating Project Maven (computer vision project for drones). During a tech antitrust hearing in US Congress, the company was questioned for opening an artificial intelligence lab in Beijing, which – according to critics – would allow the Chinese military to gain access to cutting-edge technology. Since then, Google has renewed its commitment to support the US military only.

In light of above case studies, what are the remedies to shackle infrastructural platform capitalism dominance?

i) Piketty has proposer that a capital-tax strategy as the only real alternative to an actual revolution against capitalism. He contends that such a global tax on capital or the implementation of similar taxes at the national level, for example, the Wealth Tax which is not in favour by our ruling regime, would not only restrain the current dysfunctional tendency to amass larger and larger shares of wealth at the top of the economic pyramid, but would also allow for the creation of a “social state” meeting social needs, (Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

ii)That, digital labour by focusing on the primary social aims, putting the most essential needs of people and the environment before profits. Here “the alternative to stagnation” is to provide “jobs…for the unemployed, food for the hungry, houses for homeless, adequate health care and income security and a decent environment for all of us.” The implementation of these and other human and collective goals could be made the “highest priority” to which all special interests would be subordinated. (Magdoff and Sweezy, Stagnation and the Financial Explosion, 88–90).

iii) That TNCs in discouraging their workers from further engaging in union activity is used by digital owner-lordship to put a strain on the relationship between domestic and overseas workers. For digital labour to sustainably organise for their own empowerment, the question is how we can dismantle a system that pits workers against each other in a race to the bottom, and unite to fight for a higher share of income for all workers to build transnational solidarity.

iv) that there should be a national considerations in outreaching, mobilising and organising the mass of gig- workers in the country, too: see the manifesto proposal in Towards a post-2020 political economy and newleftmalaysia, Renewal of a Socialist Ideal

EPILOGUE

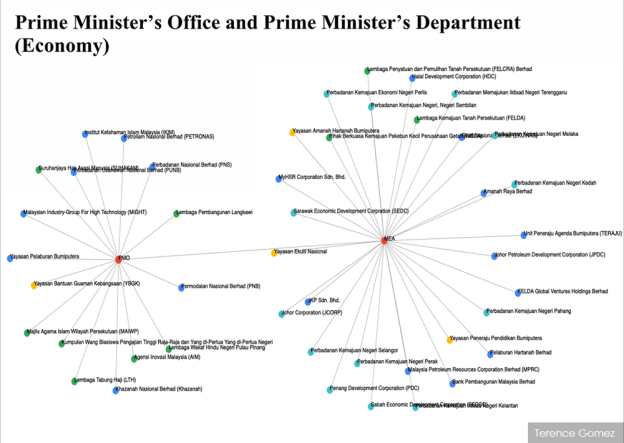

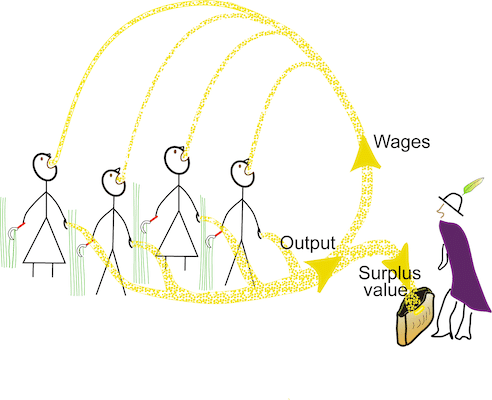

By perpetuating a “sustainable capitalism” ethos, this nation has to bear upon corporate capital and its oligarchy partners to support rakyat2 production. The monopoly-capital vagrants are profiting on our country’s resources, including talents and endowed skills, with expropriative excess, and havoc a nation state to its ecological destruction and politico-economic demise.

Any furtherance in the expansion of capitalism itself is self-defeating to humanity and has to be cleared of its excesses and excrescences. We believe that there is clear contradiction between the unlimited accumulation of capital and the preservation of society and mother earth.