10th June 2022

“Pagar makan padi”

a betrayal of trust

where the fences have been the rice crops

- INTRODUCTION

To critically indicate the defects in the New Economic Policy (NEP), one needs to probe the economics of ethnocapital, and understand the binding frameworks of capitalism, monopoly-capitalism, ethnocapitalism and the class structures that surround these parameters especially when the eradication poverty initiative – regardless of race – is a faulted policy based on a false promise.

Capitalism is the determined goal of businesses to greater accumulation of capital by increasing the value and a return on that capital asset through appreciation, rent, capital gains or interest.

The circuitry of capitalism is facilitated with monopoly-capital as the intermediary to collude and conclude transactions between capital and the ethnocapital.

A monopoly-capital enterprise is usually a Global North transnational corporation (TNC) serving a new format of imperialismu through financialization capitalism which collaborate with local compradore capital in the Global South while exploiting workers through the arbitrage of labour in depriving rakyat2 of their earned dues as a human producer.

Ethnocapital is a (malay) bumiputra owned and controlled entity performing under a rentier or clientel capitalism as a public agency, a government-linked company (GLC) or as a government-linked investment corporation (GLIC), and it can also be a privatised and or commercial enterprise like Pharmanagia or a telecommunications service provider like TM, the digital knight as an intermediary to the throne of infrastructural platforms .

From Capitalism in Crisis: Ethnocapital and Class, we have presented a macro-level overall view of ethnocratic regimes where ethnocapital is colluding with Global North monopoly-capital in depriving Global South counties of their due and fair exchanges in international trade. This article shall assess the problems on bumis‘ wealth and equity status that exist in the midst of operation of a transnational, corporate-shaped, capital-monopoly production system whereby Malaysia serves as the region’s assembly platform to service the financial capitalism in the Global North, but more importantly, it is to highlight the operational effect of such procedural activities and the consequential rent-seeking ethos effects had on racial equality and wealth equity in nation-building.

Many shall visualise a feasible, and viable, solution to the problem of wealth inequalities is to enlarge the economic pie, but persistently unfortunate is that members of the political elite are makan kueh itu (eating the cake), too, leaving rakyat2 to scramble for scraps – in a most resourceful-rich country in southeast Asia – even prior to the existence of the Majaphahit-Srivijya empires, and well before the forward advent of the western colonialists.

2. WORKERS AND CAPITALISTS

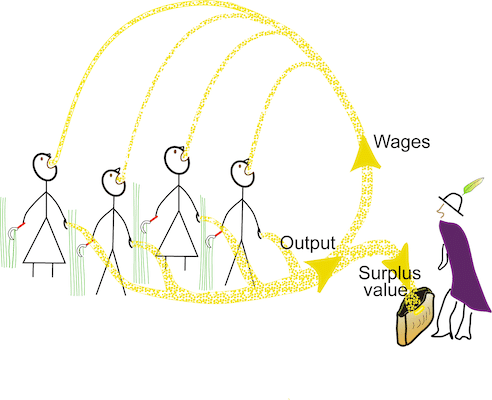

Workers under capitalism are compelled by their lack of ownership of the means of production to sell their labour power to capitalists for less than the full value of the goods they produce. Capitalists, in turn, never produce anything themselves but are, instead, able to live off the productive energies of each and every worker’s effort.

The predatory – and extractive – nature of capitalism means that the capitalist fundamental class processes are productive workers (performers) and productive capitalists (extractors). Capitalists appropriate surplus value from the consumption of labour power during the production of commodities or processing of services. The surplus is distributed among occupants of the subsumed class positions like the state, merchants, bankers, landlords, managers and monopolies. Therefore, a class position is determined by the relationship of the individual to the appropriation and distribution of the surplus value through exploitation.

In Marxian economics, the rate of exploitation is the ratio of the total amount of unpaid labour done (surplus-value) to the total amount of wages paid (the value of labour power). The rate of exploitation is known as the rate of surplus-value.

With this type of capitalism exploitative process, immiseration of the many, and alienation of everyone from the dignity of workers is ensured thoroughly.

3. NEW ETHNOCAPITAL POLICY

The New Economic Policy implemented is regarded by many rakyat2 as the new ethnocapital policy that benefits a class of ethnically capitalists – and their cohort of thieves -over the poverty poors of their own kind.

Though any of the country’s race-based policies can be traced back to the New Economic Policy (NEP), which was announced in 1970, the execution in eradicating poverty and redesigning a society by eliminating the association of any one race with specific economic functions, is deemed to fail inevitably.

Firstly, to reflect momentarily, the term Bumitisation refers to the process whereby bumiputeras (“sons of the soil”) are given preference in the control and participation of the Malaysian economy. This may take the form of equity ownership or employment opportunities at the managerial level.

This process in “malaysianisation”, however, involves, and entails, two prime aspects: firstly, the accumulation of capital on behalf of the bumiputeras; this would often means that the appointment of bumiputeras at the decision-making and managerial levels, thus structuring and managing economic nationalism within an ethnocratic (race-based) economy destiny.

That directive shall mean stuffing the civil service with a core racial identity once the private sector is fulfilled, and the Government-linked companies are overwhelmingly filled with political elites and their cohorts, most of the time with a mono-race identity.

Secondly, Malaysia’s affirmative action policy differs from those of other countries in one extremely crucial respect, and that it is “the politically dominant majority group which introduces preferential policies to raise its economic status as against that of an economically more advanced minorities“ (see Puthucheary seminal work, written while in a prison, on the Ownership and Control of the Malaysian Economy, and the continuous in-depth studies by Gomez and Jomo – collectively critical of selective privatisation and bumiputera equity quotas, and in the promotion of money politics that are detrimental to the wholesome national economic development.

Thirdly, owing to a feudal-clientiel relationship bond during colonialism, and a rentier-clientelism domain post independence but continued as neo-colonialism, we have the spectre whereby in a post-colonial society, the capitalist class in charge of the state-directed capitalism is sometimes termed the ‘bureaucratic bourgeoisie’ to represent the ruling section of the petty bourgeoisie, which is noted for its control or proximity to the state apparatus. The new ruling class in post-colonial Malaysia would comprise (political-orientated) bureaucrats, businessmen, leading politicians and professionals; where membership of such a class is determined by the criteria of occupational status, income status, education and business ownership or control over or closeness with the state apparatus, overtly or covertly, (Ahmad Fauzi Abdul Hamid, “Development in the post-Colonial State: Class, Capitalism and the Islamist Political Alternative in Malaysia“, Kajian Malaysia, Jld. XVIL No.2, Disember 1999).Therefore, it is not surprising that certain British business interests did appreciated the importance of alliance of the emerging new Malayan capitalists under a post-colonial regime, thus widening the unequal exchange in a neo-Imperialism domain.

According to a past Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIER) chairman, the recalcitrants responsible for implementing the NEP had caused its failure by letting political-oriented interests taking over economic, and economic development proper, interests.

Once this situation occurs, through the venom of unadulterated greed, the rent-seeking mentality among politician-pirates started growing to a marauders’ stage – and in expansion, coraling in, and collaborating with, every undesirables – and has since infested every layer of society – leading to corruption, odious activities and various forms of financial leakage flowing out of the country, and floundering, abroad.

4. THE ETHNOCAPITAL CLASS IN CRISIS

i] Several policies of the NEP give economic advantages to the rich Bumiputras, such as Bumiputra quotas in ownership of public company stock, and housing being sold exclusively to Bumiputras, are viewed as discriminatory. It has to be said again that when NEP was announced its goals was to have 30% of all equity in Bumiputra hands. However, NEP critics have argued that setting a target of 30% of Bumiputras trained and certified to run companies would represent a better equality in terms of opportunity.

ii] The NEP is also criticised for not dealing directly with issues of wealth distribution and economic inequality; that the policy directives no longer helps the poor but is instead an institutionalised system of handouts for the largest ethnic community in Malaysia as the NEP does not discriminate based on economic class, but whom one knows or favoured by the kleptocractic elites.

iii] there was even the setting up of a Bumiputera Prosperity Council (MKB) to empower the development of Bumiputera socio-economy, once promoted by a then Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Economy) Datuk Seri Mustapa Mohamed, in line with the Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 (SPV 2030). However, we need to ask what is “shared” : when it’s an ethnocratic collusion in social engineering on affirmative-actions – from NEP to NEM to ETP – that have morphed into a casted, and encrusted, cronyism.

iv] then, there is the statistical problems of categorising wealthy and disadvantaged Bumiputras in one group had also meant that the NEP’s goal of having 30% of the national wealth held by Bumiputras was not indicative of a median 60% of Bumiputras holding 28% of the national wealth, but could theoretically translate into one Bumiputra holding 29% of the national wealth, with the remaining Bumiputras sharing 1%.

v] Another criticism is that because of this imbalance, some Malays remain economically marginalised. In 2006, a major dispute arose when the Asian Strategic and Leadership Institute (ASLI) issued a report calculating Bumiputra-held equity had reached the 45% threshold already.

vi] This suite of figures is in fact on track with the 1997 University of Malaya study that had calculated the Bumiputra share of equity to stand at 33.7%, using par value with the bumi equity reaching the NEP target 19 years ago! (A Malaysiakini 1st. November 2006 report by Beh Lih Yi).

vii] Abang Bennet, with a piece in the

Aliran Monthly Vol 25 (2005): Issue 7 entitled UMNO: A threat to prosperity

“Umnoputeras are deeply addicted to their ethnic privileges and subsidies – but what happens when the petroleum runs out?“

viii] thus, as many has stated many a time, it is definitely associated to the differentiated social classes within the nation populace as the main problem: Alatas ,

ix] indeed, Abang Bennet had also expressed that a Martin Jalleh in the previous month issue of Aliran had provided, and presented, an astonishing account of expensive government bailouts of bungled privatisations mainly involving the crème de la crème of the crony Malay-Bumiputera community.

x] It is not a good testimony to a nation economic development when Malaysia is not only having a Malay Dilemma, but a dilemma over the continuance of an economic nationalism resting on mere ethnocratic economics.

In short, the stated elements are the indicative yet convoluted linkages between local compradore capitalists and foreign monopoly-capital enterprises that Gomez stated as “the resurgence of foreign ownership in the Malaysian economy, with companies such as Digi, Nestlé, and British American Tobacco leading the list of Malaysian companies by market capitalisation, highlighting the continuing dependence and openness of the Malaysian economy.

Rather, the state, in alliance with wealthy tycoons, was to play an increasing role in the economy, maintaining a centralisation and inequality of assets and wealth, both through systems of selective privatisation and later through the GLCs, Ownership and control in 21st century Malaysia, in newmandala as summarised by Charles Brophy, 17 JAN, 2018.

Recently, even a coalition of Malay-Muslim NGOs has objected to de facto Law Minister Takiyuddin Hassan’s statement that all Perikatan Nasional (PN) MPs who do not presently hold positions in government will be made heads of government-linked companies (GLCs) as imperfectious because GLCs performance has adequately argued by Gomez as power consolidation by a ruling regime or from Jomo urging to reconsider and undertake a GLC stake divestment strategy otherwise there could be consequential dire ramifications IDEAS.

5. WORKERS DILEMMA

With the inherent capitalism negative atrributes, many may be unaware that there are also CEOs in the GLC who take advantage of the rakyat2 toils and sweat, unmerited and unmercilessly. Those in high positions would, without any hesitation, do not care about the misery of the people who are being oppressed. In 2018 after GE14, as an example, new members of the Tabung Haji board of directors have to struggle to bring the sacred institution onto a right track. The institution was robbed several times during the previous years of Barisan Nasional administration, losing billions of dollars. Malaysians, whether Malays, Chinese, Indian, Kadazan or Iban and every other nationalities had to “bail-out” Tabung Haji RM$19 billion.

When someone in the kampung (village) got a 1.25% grant and had to wait ten years to save RM10,000 to perform the pilgrimage, then Takaful Malaysia CEO Mohamed Hassan Kamil’s income was equivalent to RM903,000 a month or RM10.84 million a year. Worse still, his income in 2019 rose by almost 17%, thus making his average monthly income in that year RM$1.05 million a month.This is equivalent to an average income of RM30,000 a day, while the majority of the pilgrims’ savings for ten years do not even reach RM700! This CEO’s salary for one day is equal to the savings of a lifetime savings of any ordinary muslim rakyat2.

Why is this allowed to happen?

At another case-company, a Tabung Haji subsidiary: the BIMB Holdings Berhad where its CEO, Mohd Muazzam Mohamed’s income in 2018 (at a time, incidentally when Tabung Haji only payout a 1.25% of grants to every poor Malays) was RM$3.12 million a year. When its annual revenue in 2017 to was increased to a mere RM$855,000, the CEO of a Tabung Haji’s subsidiary obtained a double pay increases instead.

In totality, the total remuneration for board members of Takaful Company was close to RM$1.5 million, while for BIMB Holdings it was RM$4.1 million.The chairman of BIMB Holdings earns RM375,000, while other Board members earn between RM375,000 and RM768,000 a year.

On another case-company: Sime Darby Plantation’s (SDP) annual report shows a remuneration to its then CEO, Mohd Bakke Salleh, the former Chairman of 1MDB (who was later named Telekom Chairman in a political music-chair switch). When Bakke took over as CEO at Sime Darby Plantations (SDP) his annual income was almost RM$8 million a year. His total income from being CEO there from 2011 to 2017 was RM$64 million. Yet, imterestingly, when he became CEO in 2011, SDP’s cash reserves were about RM5 billion, but it slipped to RM$500 million in 2018, while debt had risen to RM$15 billion by then.

Meanwhile, as workers are loosing their jobs, struggling to find padi and ayam (rice and chickens) for their families, and savings are running low, the EPF CEO could still afford more than a smile happily every month because according to the latest EPF annual report, the salary of the CEO and his deputies reached RM$6.1 million at one year, or an average of almost RM$130,000 per person or RM$4,300 a day. The class division between the ruling elites and ordinary rakyat2 when compared, it is an undeniable fact that 1 in 5 EPF Malaysian savers have a savings of just RM7,000!

It was reported on April 29, 2022 that Fernandes – the CEO of Capital A, formerly known as AirAsia Group Bhd – received RM14,947,213 in addition to RM124,781 in allowances for meetings, travel and other matters. Kamarudin, the executive chairman of Capital A, meanwhile received RM14,051,429.

A gig-worker earns an average of RM$3,500 per month in the Klang Valley.

6. CONCLUSION

The poor implementation of good policies, such as those related to education and technology adoption, would presently see the NEP not only failing to serve poor Bumiputera interests but also hampering the growth of the country’s economy.

Investors are already deterred by the rent-seeking and politically driven economy and, because of this political-economic direction, no jobs would be created and no skills nor technology would be transferred, resulting in the deepening of deprivation of rakyat2 in the Bottom 40 (B40) income group – the majority in this B40 group being bumiputra.

That rent-seeking is costing Malaysia easily more than 2% of its gross domestic product (GDP) is a factual reality, whereas the economy should be growing at 7% of the GDP per year, not 4.7%.

The ethnocapital capitalism crisis is creating a catastrophic case of a country in calamity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gomez and Saravanamuttu, The New Economic Policy in Malaysia Affirmative Action, Ethnic Inequalities and Social Justice, (ISEAS 2013); KS Jomo, The New Economic Policy and Interethnic Relations in Malaya, (UNRISD 2004), and Lee Hock Guan, Affirmative Action in Malaysia, Southeast Asian Affairs (2005).

R. Thillainathan and Kee-Cheok Cheong, Malaysia’s New Economic Policy, Growth and Distribution: Revisiting the Debate, Journal of Economic Studies 53(1): 51 – 68, 2016 ISSN 1511-R.

CIA, Malaysia’s Unfulfilled Promise: the New Economic Policy in Arrears, October 1985; sanitized copy approved for release on 2011/01/04.

Jomo‘s The Edge 8/01/2020 piece: https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/my-say-poverty-inequality-and-expectations

Malay Mail: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2015/09/13/economist-nep-has-outlived-its-relevance-malaysia-must-end-it-to-progress/968981 NST 14/07/20; a critique of similar model, the Pemandu’s Economic Transformation Plan (ETP) can be found in Research for Social Advancement (REFSA), A Critique of the ETP, Part I and Part II, 25/01/2012.

STORM, Illicit Capital, Illegal Trade and Inequality – Kleptocracy in Malaysia, monsoonsstorms.wordpress.com).