PROLOGUE

Nations borrowing has gone global, playing a pivotal role in the world economy by enabling national governance economic development to finance investments that ostensibly to uplift productivity and ensuring growth. However, the risks – overborrowing and potential default – haunt such national states.

1. WHAT IS SOVEREIGN DEBT?

The sovereign’s debt is a country’s national debt: the multitrillion, multinational, multicurrency network of debt obligations owed to financial capitalism of corporate bankers, global equity managers and the International Monetary Fund.

2. WHY DO SOVEREIGNS BORROW?

Governments borrow to spend beyond what they can or want to raise through general taxation. There are several economic rationales, and the parallel political motives for this activity. When tax revenues are down, such as during a recession or before an election, governments will borrow to pay for existing spending commitments to please and entice potential populace-voting cohorts.

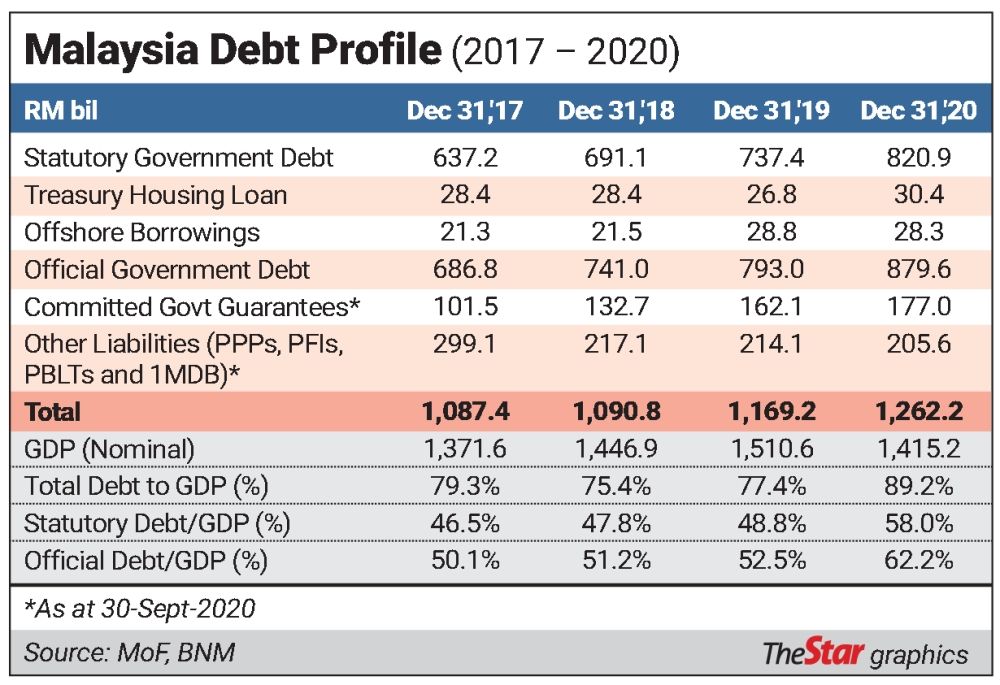

Already at 18% of federal government revenue, Malaysia’s interest payments alone will become more expensive as new debts are taken at higher rates to roll over old debt.

Often than not, it is the “tax smoothing” justification for the continuity of public services such as schools and hospitals, and highways to nowhere. It is an expressed exhortation that the government is not forced to cut spending even though an economy is already weak, the country though poor and or poorly administered, and the poverty poors are getting restless and agitated. It is something that could – and should not – make the situation worsen wider.

Indeed, governments oftentimes take a step further and actually increase spending, or reduce taxes, during a recession or before an election to try to boost growth. This “fiscal stimulus” is financed by issuing sovereign debt – using rakyat2 money.

On the other hand, these reasons cannot typically be explained by the high level of debt seen in many other countries. The frequent economic expression lies in the political motive to borrow so as to “invest in the future for a better and greater nationhood”.

Governments might borrow large sums to build a major new interstate highway, power plant, or a mass rail transit system – typically, in this country to benefit intermediary contractor cronies as part of an ethnocapital clientelship praxis.

Even though the up-front costs can be extremely high (rationalised with “these investments boost longer-term growth, justifying the borrowing“), the repayment is spread over many years – much to the glee of toll-collection and port-franchise operators. Besides the physical capital, national governments also invest in human capital, like in education and health. Again, the long-term benefits should outweigh the cost pof borrowing, provisio, the appropriate – determined and required – skilled human endowment is generated and that the health services, for instance, spread to outlying hinterlands’ communities, too.

Needless to say, effective dealing with sovereign borrowings, requires timely, fair and considered action, designed to prise economies out of debt rather than squeezing subsequent repayments through brutal politico-economic means. Any delays often increase the size of the problem and would only add to rakyat misery and suffering.

Further, forcing austerity and ‘budget balance’ on countries already suffering from falling economic activity and employment merely exacerbates the decline and puts even greater pressure on already devastated people, (Jayati Ghosh, 2023, How not to deal with a debt crisis).

3 WHO DO WE BORROW FROM ?

A Government can be very creative in finding potential lenders, as it seeks out those who might charge them the lowest interest rate. There are often trade-offs between choice of lender and terms of repayments, however.

For example, sovereigns can borrow from within their own country or from abroad.

Domestic borrowing – from local banks and asset managers or directly from households (EPF employees’ money or PNB owners’ trust units) could likely be a steady and reliable source of financing. However, there is a limited amount of money available and repayment maturities tend to be short. Not infrequently, governments also borrow from international capital markets, in larger amounts and usually at longer maturities. These markets can be fickle, however, especially for lower-income countries. It can be dangerous to assume that these lenders will always provide a readily available source of finance, (read IMF’ed).

Otherwise, there is a wide and diverse range of private sector entities willing to lend to sovereigns, too. Asset managers, such as pension funds, typically hold a large amount of government debt. They need relatively safe long-term assets to match their long-term liabilities.

Further, banks also hold large amounts of sovereign debt, especially of governments in the countries where they are based. However, this mode of “bank-sovereign nexus” has caused problems in the past. During the 2010–12 euro area sovereign debt crisis, for instance, troubled banks reduced their funding to governments, raising sovereign borrowing costs. This led to a vicious cycle of further tightening of financial conditions that aggravated the economic recession and problems in the banking system.

Finally, governments can borrow from other governments or international organizations. Often, this form of lending is not motivated primarily by commercial objectives (although a lender like the IMF may not say this in practice).

Then, there is an approach where one government might lend to another to strengthen bilateral ties. The World Bank or African Development Bank might lend money to a country to help build a waste-disposal system, to fund pandemic vaccinations, or reform the power-generation sector. And, always, the global along IMF will provide financing if a country finds itself facing balance of payments difficulties.

4 HOW DO WE BORROW?

There are various contractual ways for a government to borrow. Loans are a familiar form of financing. They are normally arranged bilaterally, or through a syndicate of lenders, and repayment is often spread out over several years.

By contrast, bonds are issued to hundreds or thousands of creditors, and the entire amount normally needs to be repaid at once.

In addition, there are many exotic instruments through which a sovereign can borrow, but these tend to be much smaller in scale.

Governments seek (hopefully) to minimize the cost of their borrowing – the interest rate – while preventing the structure of their debt from becoming too risky. For example, many governments find it cheaper to borrow in US dollars or euros than in their own currency. However, this finanancial method can cause problems if their currency depreciates, as this increases the real burden of the debt – as in the 1MDB case.

Similarly, some governments prefer to pay a fixed rate of interest on debt, as this ensures debt-service costs are stable. Oftentimes, this is seen or perceived as being cheaper (at least initially) to issue debt that is linked to a variable interest rate or consumer price inflation. However, this undertaking can be risky if these variables move in an unexpected and unfavorable direction.

Overall, though a prudent public debt structure can help keep sovereign costs low over the long run, there are many other factors that can also influence a sovereign’s creditworthiness and its borrowing costs, such as its level of economic development, the size of its financial markets, its record of honouring its obligations, and its vulnerability to external shocks, as well as global financial conditions.

As many of the above-mentioned factors are beyond the control of governments, this is where financial barons and financial vultures in the guise of sovereign rating agencies and international institutions, including the IMF, maintain elaborate models that continuously assess sovereign creditworthiness.

5 WHAT HAPPENS WHEN WE CAN’T PAY?

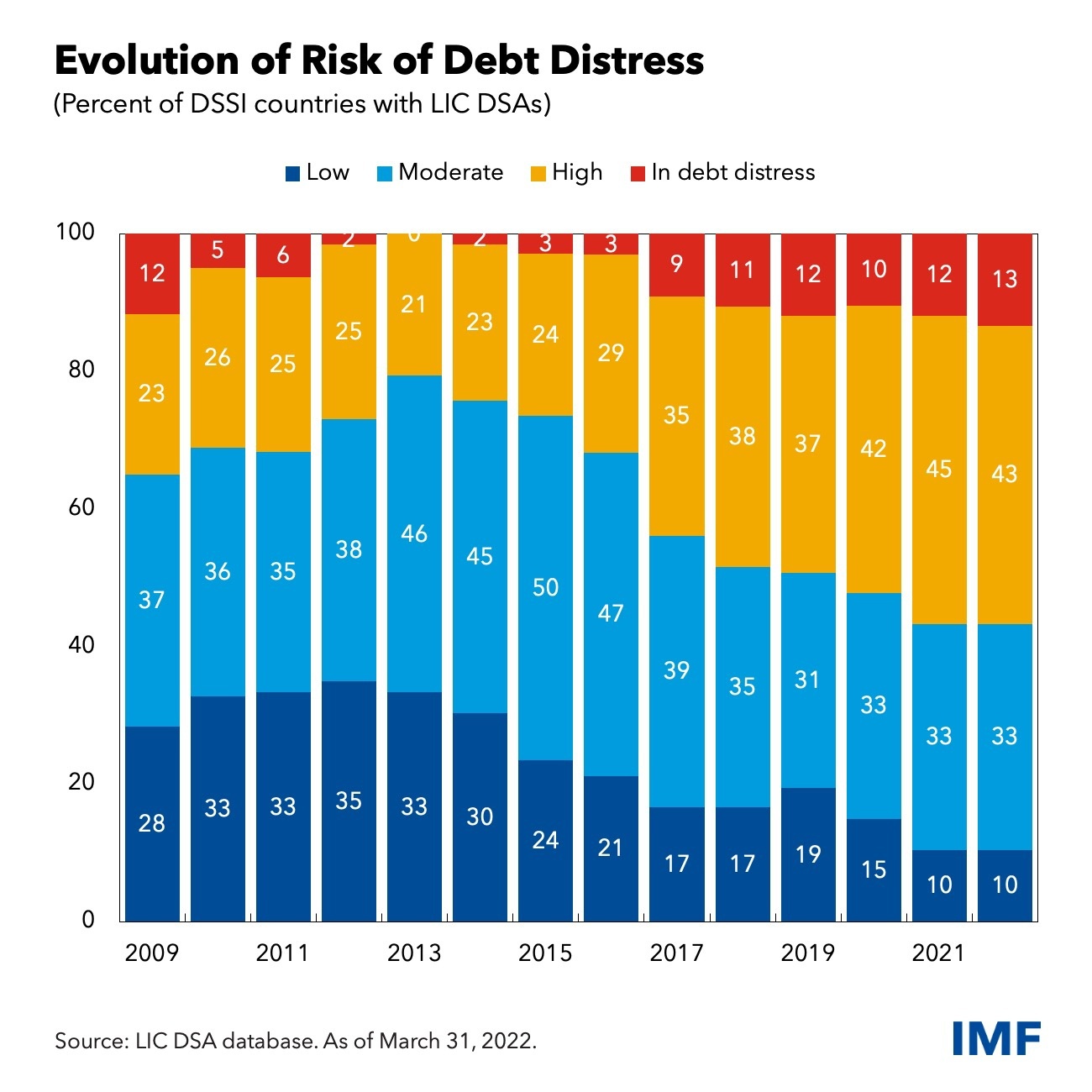

Like ordinary people and business companies, sovereigns can struggle to repay their debt. This could be because they borrowed too much or in a way that was too risky – or because they were hit by an unexpected shock, such as in a sub-Saharan deep recession, a Pakistan flood disaster or a Malaysian 1MDB financial fraud.

In these circumstances, the sovereign needs to restructure its debt. However, unlike people and companies, there is no bankruptcy court for sovereigns that can compel the debtor and its creditors to resolve the issue. Instead, it becomes a negotiation: creditors want to recover as much of their money as possible, while the borrowing country wants to regain “normal” status in financial markets, without paying out too much.

These restructurings are often costly for both the debtor and for creditors.

Well-known examples include Russia (1998), Argentina (2005), Greece (2012), and Ukraine (2015), Sri Lanka (2023 ongoing).

Costs are normally much smaller when an agreement can be reached before a sovereign state defaults, by missing a payment on its debt. These preemptive restructurings are usually resolved quickly and have smaller spillovers to the rest of the economy and financial system. However, once a sovereign defaults on its debt, the subsequent restructuring process can be long and expensive – or deadly

EPILOGUE

View 1hr 42min

RELATED READINGS

Pingback: Financial Monopoly Capitalism and the Poverty Global Poors | Towards The Malaysia Narrative