Collective on Geoeconomics

1/11/2022

PROLOGUE

There are multiple crises in country’s economic developmental effort since gaining independence that culminated to present precarious state of a nation in trillion dollar debts after six and a half decades of economic growth. By itself, each crisis is a calamity, but collectively – as each subsystem is linked with associated suprasystems – constitute the catastrophic crises of capitalism in its manifestation: meaning that there are deep structural contradictions and challenges for this country.

What distinguishes between these crises arising from factors outside of country – as exogenous crises – and those generated by contradictions within own domestic economic and political environment, as endogenous crises. Exogenous crises included the inflation that confronted the present caretaker government, the global economic instability of 2008, and the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, while endogenous crises included those associated with significant developmental phases and turning points, such as oil exploration and exploitation by and with Big Oil, FELDA land resettlement, the New Economic Policy, and Industrialization in the early 1970s, and later premature de-industrialisation and the subsequent financialisation capitalism phase. By the time of capital financialisation, the nation was engulfed with the insurgence of Political Islam, a Ketuan Melayu narrative, state corporated capitalism and increasingly an indulgence in wide-spread odious corruptive practices. In each instance, the resolution of the problems of one crisis carried within it the seeds of the next, a dialectical process which is continuing to the present period of uncertainty in economic affairs and possibility in the furtherance of political instability post-General Elections, November 2022 (GE-15).

These cascading crises are indeed not isolated incidences but formulated policies that subjugated rakyat2 to deliberated dependency to ruling regimes. Dependency Theory became closely identified with the Latin American Left in the 1960s and 1970s, when there was already a long history of such analysis (notably the work of José Carlos Mariátegui in the 1920s). The Cuban Revolution and the ideas of Che Guevara – as well as Andre Gunder Frank’s article in the Monthly Review where he stated that development of underdevelopment is about less developed countries being entrapped in dependence and dominance relationship with rich countries. Only that it also occurs when an ethnocratic governance practices kleptocracy – supported by national corporate capital that is connected to monopoly capital in the Global North that is assisting national kleptocrates to dominate their owned and controlled client states in the country.

All these crises have moments that may be budgetary or fiscal system imbalances and stresses which required policy intervention and innovative resolutions. They are regarded as “crises” in classical political economic sense that we have explored, and expanded, on many other national politico-economic issues for the past ten years in various postings and publications that shall be summarised as a dozen dimensions herein.

1 With neoliberalism economic policies as the preferred approach since independence , but without shared common prosperity nor progressive elements of developmental governance ethos or a new ideal socialist praxis referencing an equitable distribution of social wealth. The preferred present economic growth model undermines, and underdevelops, the country’s developmental effort.

This is compounded right at the birth of nation when coteries of foreign advisors from the Colonial Office, Development Advisory Service Harvard (DASH), the World Bank and International Monetary Fund – successors to IBRD and IDA – and the Asian Development Bank successively spun the narrative threads of neocolonialism, and later neoliberalism, and then bonded by neoimperialism intent that tightened the knots in dashing the country’s vision of betterment on a shared common wealth environment.

Through successive advisory consultancies – since IBRD and IDA had written a 4-volume Reports on Malaysia’s Development Prospects and Plans, surpassing the government Economic Planning Unit’s effort have few local professionals have access to “confidential reports”; the Official Secrets Act has plumbered all discrete leaks, and prevented any constructive opinion local professionals may have. Through this process, the World Bank and its twin entity the International Monetary Fund (IMF) attempted to restructuring the economy (IMF, 2001) or in implementing an infrastructure project than socio-economic considerations (World Bank 1957) to the quest of productivity growth (World Bank, 2016) and re-energise public sector (World Bank, 2019), by aiming high to achieve an accelerating growth path (World Bank, 2021), and to surge ahead (World Bank 2021b), but most catastrophically, country is still mired and entrapped within capitalism crisis to crisis in a struggle to catching up, (World Bank, 2022) among ASEAN peers:

Reinert 2007; Reinert 2009; Vries 2013; Ohlin et al have collectively argued that structural change and innovative creativeness are the keys to eradicating not only poverty, but a better prospect in sharing a common destiny.

What kind of development does a country need to share wealth within communities and between states? Then, we also need to ask what kind of institutions can promote socio-economic development? Third, how to develop? These three questions are crucial to understand why Malaysia – despite 65 years of “developmental effort” – performance outcomes that are glaringly deteriorated among emerging market countries (EMCs) in ASEAN, and even has accentuated poverty in Sabah and Sarawak states within its borders.

Schumpeter had once outlined a fundamental distinction between economic development and economic growth. This distinction helps us to approach the first question. Mere quantitative growth does not amount to economic development. Schumpeter (1934/2012: 64) had said figuratively that adding successively as many kerera api coaches as one pleases, one shall still never get a railway thereby. GDP growth nor Petronas towers, for example, do not equal an Schumpeterian economic development. Economic development ‘comes from within the economic system and is not merely an adaptation to changes in external data; it occurs discontinuously, rather than smoothly; it brings qualitative changes or “revolutions,” which fundamentally displace old equilibria and create radically new conditions’ (Elliott 2012). A country needs this kind of economic development to escape impoverishment (Reinert 2009), and rakyat² being potentially poverty poors (firestorms, 2021).

Schumpeterian institutions are concerned with the importance of innovation in generating new knowledge and modes of production, which helps move the economic activities to the next ‘stage’ or ‘paradigm’ (Reinert 2000: 11). Schumpeterian institutions tend to focus on production, and this stands in sharp contrast to the view of institutions adopted by mainstream economics and local legacy economists in the Economic Planning Unit (EPU) , which focus on the free market and trade and favours export-led and FDI-driven economic growth (Reinert 2006;Lim Mah Hui, 1982) where transnational corporations suppressed indigenous capitals and exploitated workers through labour arbitrage.

Further, Schumpeterian institutions differ from the World Bank’s conception of ‘good institutions’ including those for ‘building market institutions that promote capital growth to the detriment in poverty reduction and social benefits (World Bank 2002: III).

At a time when 70% of lower-income households cannot even meet monthly basic needs – indeed, more than 60% of these households reported having no savings at all – not much of a difference than 10 years ago:

After six and half decades of sustained neoliberalism economic developmental effort, the nation of Malaysia is still as accentuated in absolute income inequality as ever:

In short, if development in Malaysia is to be self-directed and comprehensively inclusiveness, then traits of such a “developed society should also embrace secularisation, industrialisation, commercialisation, increased social mobility, increased material standard of living and increased education and literacy besides such things as the high consumption of inanimate energy, the smaller agricultural population compared to the industrial, and the widespread social network” (Syed Hussein Alatas, in a paper presented at the Symposium on the Developmental Aims 1996, pp 70-71).

Prof Dr. Mohd Tajuddin Mohd Rasdi, Professor of Architecture, meanwhile, has extended the concept building of what is known as “beehive apartments” for urban poors where each capsule consists of basic living needs; and to allocate graduates and youths with 100 acres of farmland using the latest technology to solve national food security and rural employment, thus encouraging domestic entrepreneurship.

Related article:

Neoliberalism is Neoimperialism

2 Big Oil exploration, and exploitation of a national resource, witnessed by 1973, nine transnational corporations Big Oil with Petronas were prospecting over 156,954 square miles of the Malaysian continental shelf. This area is larger than the total land mass of the Federation of Malaysia (128,727 square miles). The rapacious character of the transnationals can only be equaled by the obscene haste of the national compradors in granting concessions to the extent of not knowing olefin from a bar of chocolate.

The country had requested national participation on a 65% / 35% government and company basis, respectively. In such a product-sharing agreement, for example, with 100,000 barrels of oil output, 40% of production is deducted from exploration and operating expenses, and the remaining 60,000 barrels to be shared on a 65% / 35% basis. Therefore, the actual result of such contract formulation was that 61% of the oil produced during any given month would go to Big Oil, and only 39% to the country.

Petronas had become the piggy bank for all Malaysia Development Plans as the country gears to an indulgence to subsidies just as it is the fund provider to the ruling regimes through the years:

Related topics:

PETRONAS Peasantry and the Proletariat

3 The New Economic Policy extension and perpetuation has meant poverty is not completely eradicted, but has aggravated with more states and among communities in deep, and widen, poverty:

And where, the poverty rate in Sabah in 2020 was the highest in the nation – more than three times the national average. The real fact is that 36 percent of all those living in poverty in Malaysia are located in Sabah.

Since Malaysia’s New Economic Policy was launched in 1971, there have been a dozen five-year Malaysia Plans, some 50 national budgets and nine prime ministers. Furthermore, 94 different Bumiputera empowerment agencies have been created and an estimated RM1 trillion (US$241 billion at current exchange rates) poured into the Bumiputera agenda, an affirmative action plan to help the majority race.

And yet, here we are still talking about how far the Bumiputeras have fallen behind the non-Bumiputeras, how targets have not been reached, how income inequalities between Malays and non-Malays are increasing, how Malays are still struggling. The reason is that all of these plans are really nothing but a racket designed to enrich kleptocractic class of political elites and their cronies at the expense of the rest of the people of Malaysia.

These recalcitrants responsible for implementing the NEP had caused its failure by letting political-oriented interests taking over politico-economic administration, and economic development management, benefiting other interests by aggravating differentiated social classes within the nation populace with the main problem ambly amplified by Alatas, Soong, Jomo, Charles Hirchman – whether as the consequential byproduct of British colonialism or the ensuing post-independence neo-colonialism. Inadvertently, the country is stuck with a no-growth but stagnated economy, (Sudhdave 2020); that the economy direction is in needs to be changed is real, (Kamal Salih, 01/06/2022) because Vision 2020 is well-blinded (Jomo, 10/12/2020).

The capitalism in crisis would continue impoverishing the poors in order for capitalism, specifically ethnocapital clientel capitalism – with the political fabrication and construction that had rapidly metamorphosed into policy constructs in the 1970s (Lim Teck Ghee) ensuing as an economic entrenchment of the NEP construct (Woo 2015, James Chin 2016, KBN 2018, Khalid 2019, KRI 2020, Kua 2021 & Diam 2021) which clearly is divisive to the nation’s unity and sense of belonging – to exist and flourish.

Thus, the mere thought in the creation of a Bumiputera

middle class to make the Malays more substantive players in economic growth, but instead the outcome resultans are the neglected poor’s and marginalized Orang Alsi/Asal.

Even in the arena of socio-economic management of marginalised segment of society, however, the country had fallen short. Though the social protection system reaches targeted populace, the benefits to the B20 segment is negligible.

Abang Bennet with a piece in Aliran Monthly Vol 25 (2005): Issue 7 entitled UMNO: A threat to prosperity whence a political entity is unyielding in promoting Malay political ascendancy, ends with a failure to develop and promote a genuinely Malaysian political outlook as the immediate consequence of this unwillingness in sharing wealth except to and among its own class.

Bumiputera in the top income groups (the top 1 per cent and the 10 per cent) benefited the most, (see Khalid lse.blog, 2019)

Related articles:

4 Industrialisation, in World Bank’s World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains tends to portray capitalism and its inherited globalisation thrust in a global value chaining process as the contribution to poor countries’ development through job creation, poverty alleviation, and economic growth. However, upon interrogating some data, there are sufficient evidence to show a contradictory trend.

One of key arguments for emerging new independent state is to go for industrialisation in seek of comparative advantage whereby firms are more likely to specialize in the tasks in which they are most productive. Second, firms are able to gain from connections with foreign firms, which pass on the best managerial and technological practices countries enjoy faster income growth and falling poverty. What often omitted to mention are transnational corporations in seeking labour arbitrage advantages, and if any labour conflict arise, then to proceed to union busting.

As a result, the initiated industrialisation programme in the 1970s had not promote wide employment, but greater encroachment of transnational corporations (TNCs) in the country. This is about monopoly-capital extracting resources while subjugating workers rights to fair wages and the extraction of surplus value in a dominated country to protect capital.

According to the International Labour Organization, between 1995 and 2013 the number of people employed in global value chains rose from 296 to 453 million, amounting to one in five jobs in the global economy.

However, past performance had shown that there were low employment absorption capacity in the manufacturing sector, especially in the pioneer companies; in fact, the manufacturing sector provided only 5,500 new jobs per year during 1966/67,(Lo Sum-Yee, The Development Performance of West Malaysia, 1955-1967, with special reference to the industrial sector, and E.L.Wheelwright, Industrialisation in Malaysia.

The global value chain (GVC) world also enhances the dominance of transnational corporations (TNCs), concentrates wealth, represses the incomes of supplier firms in developing countries, and creates many bad jobs (degrading, dirty, dangerous) that demand foreign labour intake with deleterious outcomes for local workers, but if they do protest on working conditions whether through go-slow or collective strikes, union busting by TNCs becomes the directive norms.

Further, in such a globalised scenario of commodity supply chain, the safety of blue waterways is crucial and the geoeconomics of trade routes are vital to pan-regional system of trade and investment as the country tries to remain relevant in the geopolitics of the Asia-Pacific strategy.

More worrisome essentially, the foreign direct investment has been decreasing:

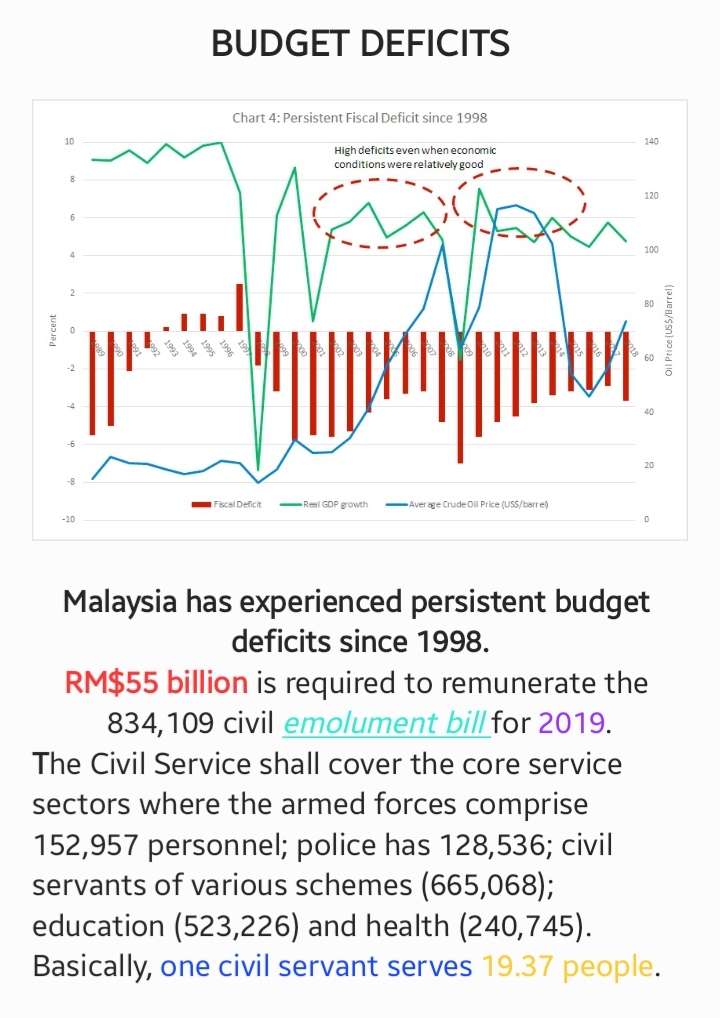

whereas the national debts are increasing as a resultant outcome of continous high operation expenditure with consistent budget deficits since 1998:

with an outsized public sector which is imperfect in its non-productiveness (reference: World Bank (2019). Malaysia Economic Monitor: Re-energizing the Public Service):

It is unsurprising that through the years Malaysian manufacturing prowess is uneven, and at times, had deteriorated; during the pandemic, it is definitely not doing well:

Recent decision to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a trade bloc among 11 countries that aims to reduce trade barriers and facilitate trade among member states has been met with disapproval by NGOs. More pertinent objections are when the PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) Cost Benefits Analysis was published indicating “gaps” and “many questionable claims of benefits”.

Covering these trading disadvantages include:

- Malaysia’s trade imports could increase to more than USD 2 billion a year compared to exports when import tariffs are brought down to 0%.

- Job losses are expected when Malaysia is flooded with imported products at more competitive prices compared to local small and medium-sized enterprise (SME)-manufactured products.

- Increased imports of agricultural products would likely eliminate the livelihood of local agro-food producers.

- CPTPP requires that Malaysia signs up to the 1991 International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) convention, which prohibits seed sharing amongst local farmers, making them beholden to Big Farms agro corporations to procure their seeds, fertilisers and pesticides.

- Wide power granted to foreign investors under CPTPP that would tie the Government’s hands to implement affirmative action to the rakyat.

- Corporations are empowered to sue the Malaysian Government if it does not honor the rights given to their investments as per the CPTPP.

This Agreement is no better than Obama’s TPPA abrogated by the Trump’s administration.

Related articles:

Precarious Labour in Industrialisation Capitalism

5 Financialization Capitalism emerged as compradore capitalists marginalised in the industrislisation process with lesser economic incentives than the monopoly capitalised transnational corporations. Ethnocapital also felt that a prematured de-industrialisation in 1990s would benefit the ruling class much more easily than producing and marketing physical goods. The financialisation of capitalism that emerged harmed an industrial E&E ecosystem that the latter were nurturing, thus limiting human resources enhancement and deployment, besides not tapping and/or enforcing upon TNCs’ technology-transfer to Malaysia.

The financialization capitalism becomes a pathway towards the widening accumulation of capital. The ensuing profit generated in companies, and the rent elements received by oligarchy individuals, inevitably perpetuate the extraction of outsized surplus values relative to capital “invested”.

It also highlights the longer term on how to rebalancing towards deregulated finance and foundational service sectors (like infrastructural platforms which are incrementally becoming invasive as techno-feudalism in country) franchised by privatisation and outsourcing to Global North monopoly-capital whereby compradore capital accumulates their capital as functioning intermediaries.

Related article:

Rentier Capitalism follows concurrently with financialisation capitalism engendering an ethnocapital environment that only reinforces all the negative aspects of NEP and kleptocracy excessively indulgence on value extraction.

The fact that the financial capitalisation of the economy, post-1990s coupled to an earlier de-industrialisation process, (Rajah Rasiah, 2011) has accentuated and expanded monetary instruments circulation unfavourably:

In short, the amount of money floating around is not to generate wealth but within the circuit of financialization capitalism components of FIREs (finance, interests, real estate) in furtherance of repaying mortgage loans, hire purchases, insurances, real estates tax dues and other debt interests to rent-seekers not having to produce physical goods to accumulate capital wealth.

Any social conscious government would know that affirmative action policies should prioritise sectors that have large multiplier effects – that the benefits from such assistance should be spread out to the public and not just be limited to the recipients, and the intermediaries (rentier capitalists) distributing them. Affirmative policies tend to degenerate into perverse patronage and political clientelism, thereby creating a breeding ground for the rent-seeking leeches to suck the life blood of an economy.

Related article:

Class Analysis of Ethnocapitalism

6 The O&G explorations with Big Oil, the NEP implementation and initialisation of an industrialisation program went hand-in-hand as an expression of economic nationalism with the Guthrie Dawn Raid that formed eventually part of the FELDA scheme stable. However, the story of FELDA to FGV – Cultivators and Capital becomes one of corporate capital exploiting FELDA settler-tenants’ hard-earned incomes into debts repayments with the corporatisation of FELDA land and properties into as the Felda Global Venture (FGV) as another dependency development model

FELDA – a corridor sanitarian was imaged to corral rural Malays to forestall agrarian-urban collaboration with FTZ industrial workers for revolutionary changes. However, the indebtedness to the second-generation of FELDA settlers only aggravated with aggregation in corporate capital’s FGV misadventure as one more odious financial transactions that connected to the suprasystem link destined to debts eventually.

7 Corruptive practices that follow only witness the insurgence of a systemic odious culture that permeated throughout the nation.

From the 1MDB to the suite of cases like the Littoral Combat Ship scandal, the Private Finance Initiatives, and PKFS scandal only displayed the country as a pirated ship plowing waves after waves drowning rakyat2 wealth in its wakes.

These are the sins of commission, omission, and dereliction – of responsibilities that have infiltrated, and enveloped and permeated, the government of a nation state that is bankrupted with ideas to develop but to loot national wealth.

It must further be revealed that the nation had already paid out RM$1.7 billion to service the 1MDB company’s loan interests using RM$459 million from the development allocation and another RM$1.241 billion from the Assets Recovery Trust Account.

That ARTA as of Dec 31, 2021, has only RM$15.281 billion balance presently.

Related article:

8 The public sector, supporting the dastard nature of kleptocractic practices, has not met the performance criteria deemed a necessity to enhance economic development, but unfurnished as an intermediary medium between political master and to rentier capitalism, and some elements have aligned to gorging unfetted gains with the political kleptocrats and clientele capitalists.

Not infrequent harsh critique of an ethno-administrative regime is the poor performance of the civil service, its sluggish deliverance of public goods and services, slackness in work productivity, and widening misuse of public funds.

All the above issues are aided and abetted by neoliberalism capital endowment in the guise of foreign advisors to dash any hope of an indigenous contribution to proper economic development but an economic growth praxis that engulfed a state of nation crises after crises with subservient subsidies that inhibit an alternative mode in enhancing the development of a country.

9 The government-linked companies as capitalism state corporations, only perpetuated the ethnocapital strongholds on the country.

The GLC world is very closely linked to the policy world, and the policy world is very closely linked to the world of politics. That is the rogue elephant in the political room.

“Why is there no attempt to deconstruct this GLC monster — to shape it up and use it properly? Because there is no political will to do so,” so said economist Terence Gomez once.

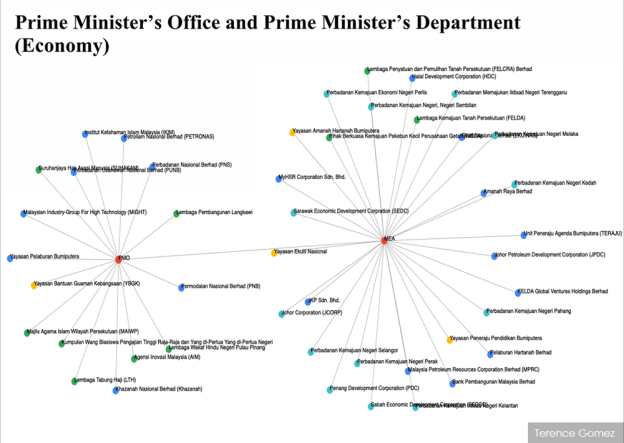

The concentration of control by the Prime Minister department and the Ministry of Finance are overwhelmingly dominating :

When PH came into power, the new government did nothing either, as it realised that it could also utilise the GLCs to its benefit.

Related readings:

Class Analysis of Corporate Capital

10 Political Islam ascendency whence increasingly, the voice of liberalism has been articulating that Malaysia’s constitution is secular and it is not an Islamic state or Negara Islam (as was proclaimed by then Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamad, in September 2001) as there are many attempts to give Muslim law a bigger presence in the country’s legal system. In a piece entitled “Kembalikan Kegemilangan Undang Islam,” (Utusan Malaysia Feb 27, 2014), Zainul Rijal Abu Bakar had attempted to made an argument that “Islamic law” is a “grundnorm” or the “primary norm” in Malaysian law and politics. Basing on the Kelsen’s theory of legality, law is deemed to be neutral about the ethical identity of the state, and as such Islamic Law cannot be the Constitutional Norm (R. Rueban Balasubramaniam, 2014). However, even though the 1957 Federal Constitution had outlined a limited role for the states to administer “Muslim law”, since 1976 a constitutional amendment had amended “Muslim courts” to read “Syariah courts.”

The change in wording soon appeared in statutory law: the Muslim Family Law Act became the Islamic Family Law Act; the Administration of Muslim Law Act became the Administration of Islamic Law Act; the Muslim Criminal Law Offenses Act became the Syariah Criminal Offenses Act; the Muslim Criminal Procedure Act became the Syariah Criminal Procedure Act, and so forth, giving rise to increasing political Islamism in the country.

Already the role of Islam is manifested in many ways:

- Funding of mosques and other Islamic places of worship from various sources

- Government funding in support of an Islamic religious establishment

- Government policy to “infuse Islamic values” into state administration

- Religious Affairs Department receives zakat from Muslims.

- Zakat through enrichment programs funded Muslim children extra education

- Mosque or surau must be in every new property development.

[ To read also Kikue Hamayotsu: Once a Muslim Always a Muslim that gives credence to the argument that Islam is used simply as a means to ensure the continuation of a corrupt regime ].

The question on how the Malaysian-style of racial accommodation is able to survive when the overall nation-building program had been attempting to look at the three main angles of ideology, race and ethnicity as the nation-building, but without any definitive vision of national goal.

12 The prime problem in country’s politico-economic environment is the feudal structure encased in an ethnocapital domain that perpetuated within the veil of Ketuan Melayu leadership. This domination in political governance – unequal and injustifiable – exists and sustains to the state of a Ketuanan Melayu (Jawi script: كتوانن ملايو; lit. (“Malay Overlordship“) is a political concept that tends to over-emphasises Malay preeminence in present-day Malaysia. The Malays of Malaysia have claimed a special position and exceptional rights owing to their perceived comparative longer history in the region and the fact that the present Malaysian state itself evolved from a Malay statehood as narrated.

Pursuant to this Islamic narrative is the spawning political conflicts and economic disparities among the people through race/religion identity politics for wealth accumulation at the top of the social pyramid.

After the post-1969 riots, the Malay establishment (in the appearance of the UMNO political entity and the guise of feudal-royals’ households) had abandoned multiracial politics in favour of the Malay Supremacy ideology. Under Ketuanan Melayu, Malays were behaving superior in all aspects, particularly in the realm of politics that became known as the Malay Agenda. Given that Malay and Islam were synonymous, Malay supremacy was equivalent to Islamic supremacy, too.

Related article:

Clientel Ethnocapital Colonialism

EPILOGUE

The Malay community’s mainstream view on political identity is summed up by James Chin as:

1) Identity Politics in Malaysia is driven by the ideology of Ketuanan Melayu Islam. Most of the Malay elites (Malay political leaders, Islamic religious leaders and JAKIM/bureaucracy) have interpreted the “special position” and “religion of the federation” in the Federal Constitution to mean that the Malays and Islam are politically supreme over all other ethnic and religious groups in Malaysia.

There is due reluctance to accept that Malaysia is a multi-cultural, multi-faith country. Nor do this faulted view consider the totally different environment in the Borneo States of Sabah and Sarawak.

2) The main Malay-based political parties, UMNO and PAS, and more recently PBBM, have all decided that political mobilisation must be based on Malays and Islam, thus reinforcing the beliefs of Ketuanan Melayu Islam. This process is assisted by the network of Malay-Islamic NGOs and private Islamic schools (madrasa like Hanbali, Hanafi, Maliki, and Shafei) resulting in Malay and Muslim community in Malaysia are increasing becoming more intolerant, insensitive, conservative, and even authoritarian.

3) The bureaucratisation of Islam especially by JAKIM perperuates a self-reinforcing blanketed ecosystem. Further, it has created a state-defined version of Sunni Islam for Malaysia and exclude all other Islamic sects which do not conform to this, especially the Shi’a. It is often expressed that JAKIM – and the religious elite – is not only supported generously by the state but is so powerful now that even political leaders fear confronting it (Tawfik Ismail).

4) The ultimate aim of those supporting the Ketuanan Melayu Islam is to create a Malay-Islamic state – an unique version where ethnicity is a major constituting component. This is in direct contradiction of basic Islamic tenets against racism.

Identity politics in Malaysia is inherently intertwined with the rise of political Islam and the creation of Ketuanan Melayu Islam. This unique brand of Islamic supremacy with a racial component has thus, most lamentably, bred an increasingly intolerant and exclusive variety of Islam in Malaysia that will lead the country down a path to nowhere but a society that is less receptive to open dialogue and being less progressive in thoughts and deeds.

Therefore, there is this Umno-produced collapse of Malay political coherence at the centre of national politics emerging. The related failure to develop and promote a genuinely Malaysian political outlook to replace the “rhetoric of Malayness” as the basis of national life, is also the reason for the uncertainty and open-endedness of the current situation as once opined, and again lately, by Clive Kessler.

You must be logged in to post a comment.