Collective on Geoeconomics

30/01/2023

PROLOGUE

As countries try to recover and emerge from the pandemic, the firm rise in demand for intermediate inputs with energetic manufacturing activity, there arises a demand for container shipments. However, shipping capacity has been constrained by logistical hurdles and bottlenecks and even shortages in container shipping equipment. On top of these existing problems are also the unscheduled wharf disruptions and port congestions that have led to a surge in surcharges fees, including demurrage and detention fees.

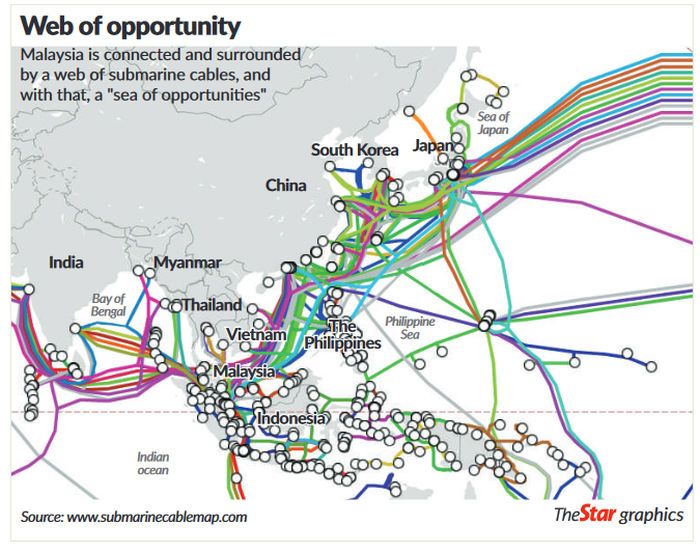

Beneath the blue waterways, another geoeconomic submarine warfare is surfacing under the guise of infrastructural platforms as part of the netarchical capitalism torpedo-battle with a new governance.

1] INTRODUCTION

By the second half of 2020, shipping costs have soared. Since October 2021, cost indicatots of shipping containers by maritime freight had pointed to an increase of over 500 percent from their pre-pandemic levels, while the cost of shipping bulk commodities by sea had tripled (Fig. 2).

The geoeconomics of ports and ships are that in 2020, 41.8% of the world’s exports and 38.2% of global imports come to or from Asia and the Pacific, (ESCAP, 2020).

2] WHO ARE THE INFRASTRACTURAL PLATFORMS

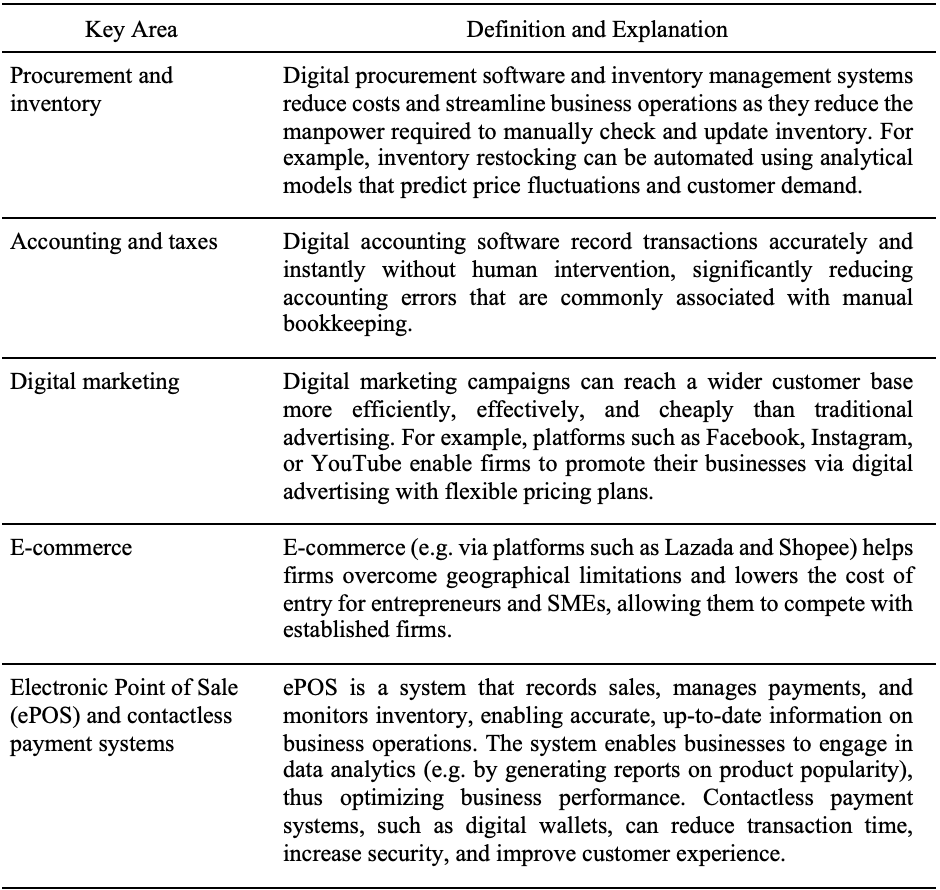

Since raw data, processed information and uninterrupted communications are of prime importance in a globalised geoeconomic environment, the installation, repairs and maintenance of the underwater cables in the country are with these infrastructural platform players of tech giants such as Google, Amazon and Microsoft, and the national internet exchange body, Malaysian Internet Exchange.

On the other hand, cabotage involves laws put in place to protect domestic shipping industries from foreign competition.

2] WHAT ARE THE INFRASTRUCTURAL PLATFORMS PROBLEMS

According to the infrastructural platform entities, the requisite domestic shipping licensing exemption (DSLE), which allows a ship to undertake submarine cable repairs, can take up to 27 days to obtain in Malaysia. This is in contrast to 20 days in the Philippines, 19 days in Singapore and 12 days in Vietnam.

There were also other issues including that the foreign-flagged vessels selected to undertake submarine cable repairs had to be endorsed by the Malaysian Ship Owners Association or MASA, which would have to confirm that there was no locally registered vessel capable of handling the required function.

The infrastructural platform tech giants had further alluded that MASA was looking to protect its members and blocking foreign-flagged shipping companies from operating in Malaysian waters, which led to delays in getting approval for vessels to maintain and repair undersea fibre-optic cablelines in Malaysian waters.

3] WHY ARE THE INFRASTRUCTURAL PLATFORMS COMPLAINING

That the implementation of the cabotage policy by previous transport minister Wee Ka Siong is inappropriate and inconsistent with the Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint, which was meant to spearhead Malaysia’s progress as a technologically advanced economy.

These infrastructural platform entities had contended that the technology pathway is predicated upon having fast and reliable internet connectivity, which in turn requires a supportive regulatory environment that would then encourage further investment in digital communication and its connectivity.

4] WHEN DID THESE ISSUES AROSE

The infrastructural platform players had contacted to previous prime ministers Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin in November 2020 and Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob in September 2021, for the exemption under Section 65U of the Merchant Shipping Ordinance 1952 to revoke an exemption for vessels involved in submarine cable repairs.

His predecessor, encik Anthony Loke, had approved submarine cable repair vessels from being exempted from the cabotage laws in March 2019.

There were also appeals made to the then science, technology and innovation minister, Khairy Jamaluddin, in mid-January 2021, to help resolve their problems, but nothing came of it nor the cabotage matter resolved.

5] HOW OTHER CAPITAL PLAYERS ARE INVOLVED

Much of the undersea cable repairs have been undertaken by Asean Cable Ship Pte Ltd (ACPL), which operates three vessels — Asean Explorer and Asean Protector where both are flagged in Indonesia, and Asean Restorer which is registered in Singapore.

ACPL was set up by the Asean Telecommunications Authorities — Telekom Malaysia Bhd, CAT Telecom Public Co Ltd, Eastern Telecommunications, PT Indosat Tbk, Telekom Brunei Bhd and Singapore Telecommunications Ltd.

6] WHERE ARE CLIENTELE CAPITAL COLLABORATING

Telekom Malaysia’s largest shareholder is government-controlled Khazanah Nasional Bhd, which has a 20.11% stake. As at mid-March 2022, government-linked agencies Khazanah, Employees’ Provident Fund, Permodalan Nasional Bhd, Kumpulan Wang Persaraan (Diperbadankan) and Pertubuhan Keselamatan Sosial controlled about 60% of Telekom Malaysia’s stock.

OMS Group Sdn Bhd — another undersea cable repair company with five cable repair ships and two barges, some of which are flagged in Malaysia — has also been handling repairs for submarine cables locally.

OMS – a Malaysian company controlled by businessman Datuk Lim Soon Foo – is the only company in Malaysia that claims to have undersea cable submarine repair capabilities and the largest beneficiary of the cabotage policy, (I³ Investor, 2021).

7] HOW TO PROCEED

Since this marine issue is with regard to the Malaysian cabotage policy pertaining to submarine cable repairs came about in mid-November 2020 after previous transport minister Datuk Seri Wee Ka Siong exercised his powers under Section 65U of the Merchant Shipping Ordinance 1952 to revoke an exemption for vessels involved in submarine cable repairs, and that his predecessor, Anthony Loke, had approved these submarine cable repair vessels from being exempted from the cabotage laws in March 2019, the untangling has to be executed by present government, and encik Loke as the present transport minister once again.

8] WHAT ARE OUR POSITIONS TOWARD INFRASTRUCTURAL PLATFORM PREDATORS

The country has promoted the cabotage policy mainly to develop local know-how and expertise to support a national digital economy.

The country needs local expertise to ensure our national undersea cables are well maintained and not to be wholesomely dependent on Global North monopoly-capital corporations on an unequal economic and inaccessible technological exchanges.

That the international infrastructural platforms had once threatened to withdraw in cooperating with the national digital economic aspiration is uncalled for.

It is unbecoming and unbelieving for foreign investors – specifically Global North monopoly-capital corporates – not wanting to partner local expertise to provide support and services on their financialised capital but monopoly investment.

It is also most improper that when an undersea cable is cut and requires immediate attention, is it not that a national presence is better than relying on foreign vessels as a first choice?

That this ensuing case is a question of national security and that the country is at risk when foreign undersea repair ships are allowed to be operating freely in sovereign Malaysian waters.

9] WHO WHY WHAT WHERE WHEN NETARCHICAL CAPITALISM BE BURIED UNDERSEA

Digital infrastructural platforms are like neoliberal connotation of colonial ‘forward movement’ activities or ‘colonial intervention’ or better termed as anything but colonialisation where lands are to be discovered and conquered, and natural resources to be expropriated and labour to be exploited.

Under present environment of a digital economy, whoever gets there first, and holds fast and tight, shall get their information server-riches. The infrastructural platform kings (colonial-feudal lords) position themselves above end-users (the colonised), and their data surfing activities (serfs’ farm cultivation), thereby giving them overwhelming privileged access (lordship) to record and retrieve (dictate and dominate) end-users (the serfs and slaves) as and when demanded (as surplus value expropriation) under an information-commodity chained monopoly-capital domain (via routers and cloud servers) .

To gain, and accumulate, capital on behalf of the infrastructural platform kingdoms are the telecommunication intermediary knights riding on their Internet of Things to provide, partition and protect, information services to their surfing serfs.

It is the emergence of a new business model of large monopolistic firms on digital platforms that are capable of extracting immense amounts of data overwhelming legacy enterprises and suppressing labour empowerment, (Paul Langley and Andrew Leyshon, Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalisation of digital economic circulation, 2020).

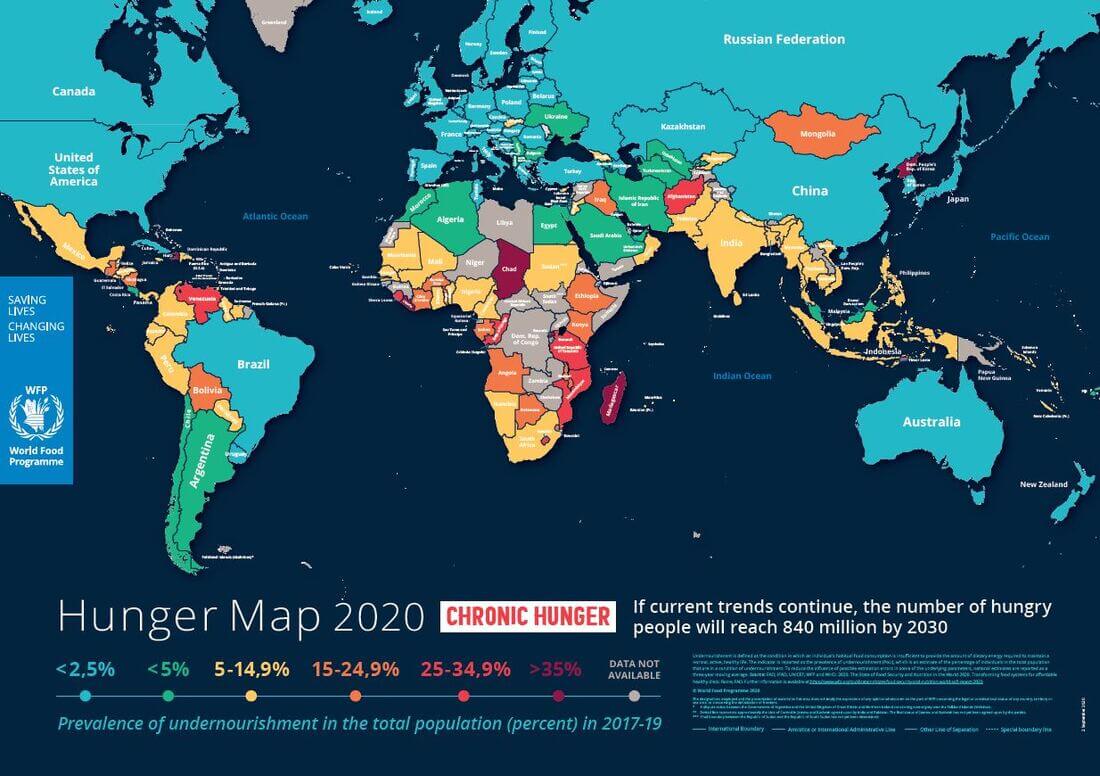

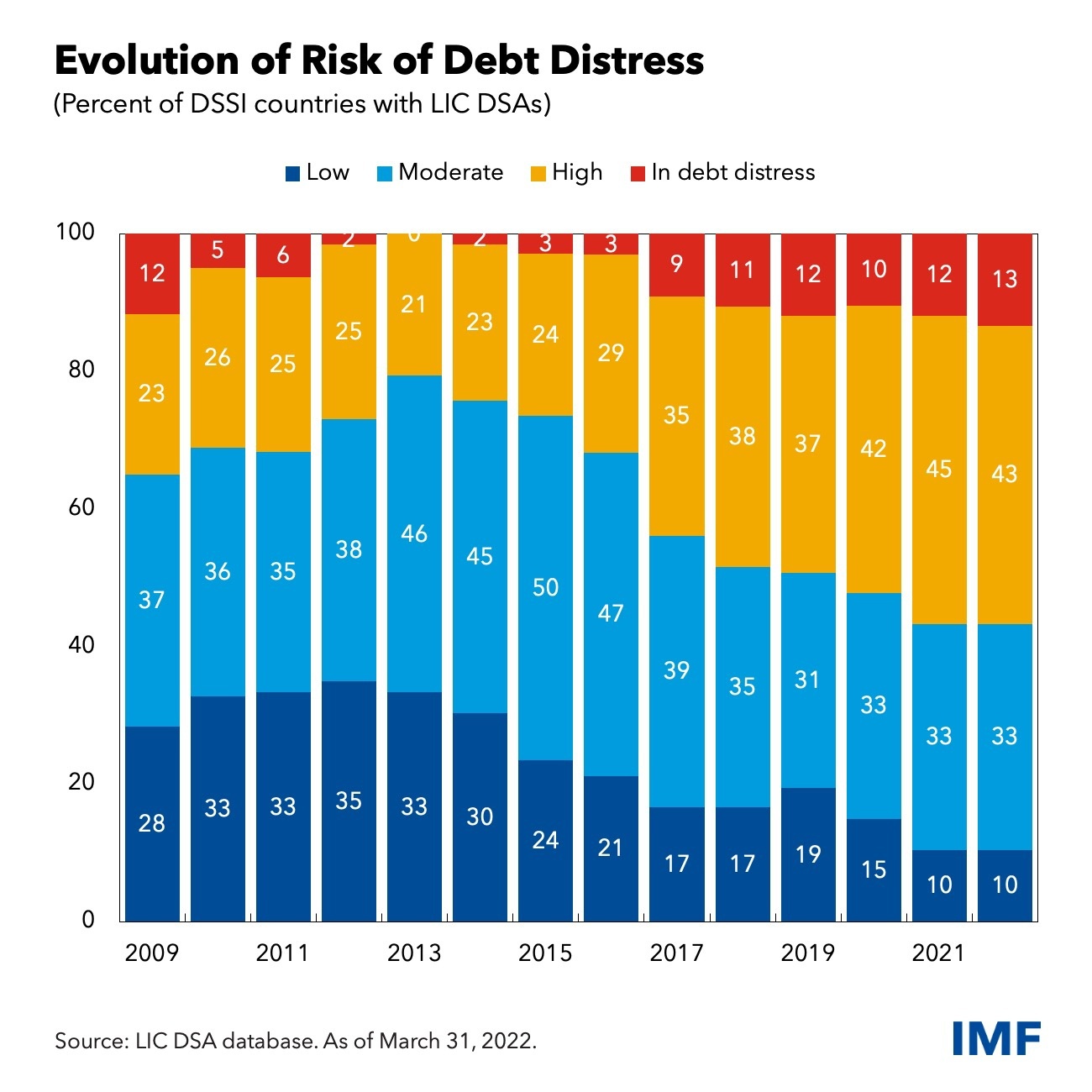

10] At a time of an epidemiological-economic-ecological polycrisis, many national banks accelerated the monetary flow – and the resulting wave of liquidity – leading to substantial increases in corporate wealth in many developed and advanced economies, whereas the emerging and low income economies face external debt distress compounding poverty of the global

poors, (World Bank 2022). As a result of falling income levels, widespread employment losses and widening fiscal deficits, (UNCTAD 2020) – a rakyat-oriented governance should not allow vulture-capitalism in the shape of infrastructural platforms be roaming the waves of high blue waterways as predatory pirates.

Related Readings

You must be logged in to post a comment.