collective on Geoeconomics

30th January 2023

1] INTRODUCTION

Around the world: private equity funds are ploughing pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowment funds and investments from governments, banks, insurance companies and even high net-worth individuals tilting financial monopoly-capital into the agriculture sector.

Big Farms are in many ways undermining local and regional food security by buying up land and entrenching an industrial, export-oriented model of agriculture. In the process – with wide-spread circuitry of capital, the inadvertent existence of monopoly-capital – large transnational conglomerates are not only expropriating emerging economies their natural resources in an unequal exchange, but also inducing long-term environmental and social devastation as a consequential ecosystem disaster.

2] GLOBALISATION OF AGRIBUSINESS

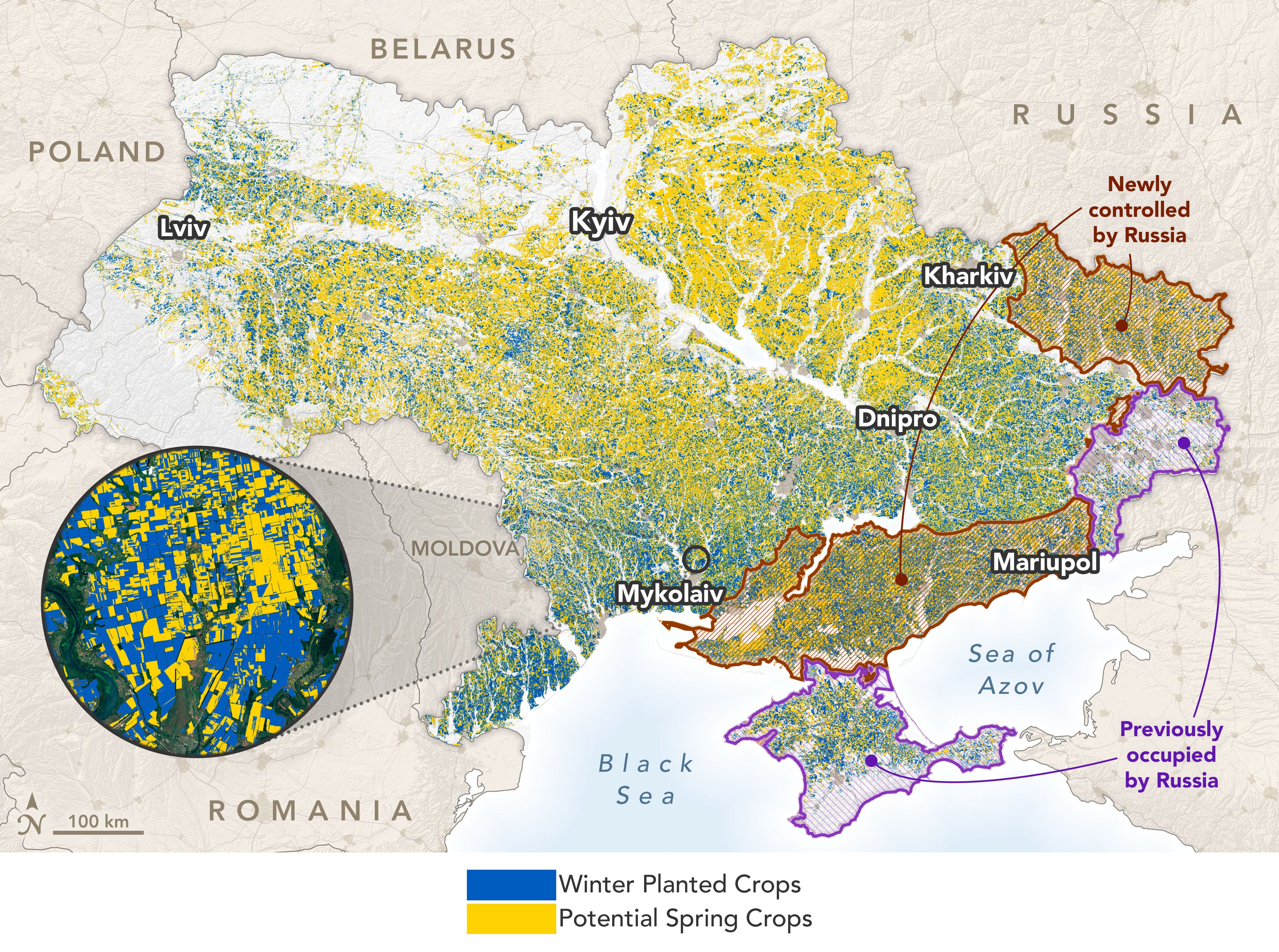

In September 2020, Grain.org indicated that monopoly-capital is using money to lease or buy up farms on the cheap and aggregate them into large-scale, US-style grain and soybean concerns. In fact, several offshore tax havens and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development had targeted Ukraine in particular.

That country contains one third of all arable land in Europe. A 2015 article by Oriental Review noted that, since the mid-90s, Ukrainian-Americans in the US-Ukraine Business Council have been instrumental in encouraging the foreign control of Ukrainian agriculture.

In another instance, soy has become one of the world’s most important agro-industrial commodities – serving as the nexus for the production of food, animal feed, fuel and hundreds of industrial products – and South America has become its leading production region. However, the soy boom on this continent entangles transnational capital and commodity flows and disrupted social relations deeply in contested ecologies and economies, see The Journal of Peasant Studies : Soy Production in South America: Globalization and New Agroindustrial Landscapes and John Wilkinson, The Globalization of Agribusiness and Developing World Food Systems, Monthly Review, Sep 01, 2009.

Most of the new soy crops are located in savanna and dry forest regions – the Cerrado in Brazil and the Gran Chaco in Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia.

However, some new croplands have eaten into rainforests. For instance, soybean fields in the Brazilian Amazon increased more than tenfold over the two decades. About 32 percent of the new fields were planted among primary tropical rainforests, often in areas that had first been cleared for cattle pastures,(nasa.gov).

The outcome is that transnationals have had a dominant presence in the Brazilian agrifood industry since its genesis; players have include: Nestlé, Unilever, Anderson Clayton, Corn Products Company, Dreyfus, and the Argentine transnational Bunge y Borne (now simply Bunge). They were later followed, as different market segments matured, by Kraft, Nabisco, General Foods, and Cargill from the United States, and United Biscuits, Bongrain, Danone, Parmalat, and Carrefour from Europe.

In Africa, the IMF, under its Structural Adjustment Programme, or the World Bank, often imposed upon African debtor countries to develop their exports of cash crops at the expense of imports and expenditure on social welfare, resulting in cutting subsidies into local food production.

Food aid that is sent to Ethiopia, which could do a better job of feeding itself if the coffee price was not driven down by commodity markets in London or New York. In Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, food aid does not reach all needy inhabitants because of their political affiliations.

Then, we have a case-firm like chocolate firm Hershey purchasing so many cocoa beans in the futures market that prices rose by more than 30 percent; the Ghana Cocoa Board had accused the firm on the abuse of the derivatives market to impoverish the West African farmer.

In Jamaica, it means that local food industries go out of business because of the dumping of cheap, subsidised food from the USA.

Nearer to Asia, Malaysia’s agricultural sector is strongly biased towards large-scale agriculture. The estate (plantation) sector is predominantly a producer of oil palm and rubber accounting for 70% of the country’s agricultural area. These estates are big – each individual unit commonly covering 2,000-10,000 hectares, managed by global companies such as Sime Darby which controls over 300,000 hectares in Malaysia.

Malaysia land development schemes, started by the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA), are managed like a feudal land-owner than as a co-operative occupying 21% of the land; read Big Capital Small Farmers.

With adherence to the neo-colonial praxis in financial corporatisation of large agribusiness plantations catering to metropolitan countries commercial needs, a country like Malaysia had neglected her domestic food security concern so much that the country imports almost 100% of grain corn or two million tonnes annually from Argentina, Brazil and the US.

The local rice production has stagnated in the last thirty years and between 2016 to 2018, rice production actually decreased by 6.20%. As by today, Malaysia is importing between 30 to 40 per cent of its rice consumption mainly from Vietnam, India and Thailand.

3] CONSEQUENCES of FINANCIALISATION CAPITALISM

Although modern human societies have attained an unprecedented levels of wealth, there is a significant amount of the world’s population continues to suffer from hunger or food insecurity on a daily basis. In Agriculture and Food in Crisis, Fred Magdoff and Brian Tokar said that nowhere more evident than in the production and distribution of food.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) had stated that wheat and fertilizer supply shortages have driven up prices and increased food import bills for the most vulnerable countries by more than $25 billion, putting 1.7 billion people at risk of going hungry.

The persistence foray of metropolitan corporate capital from Global North only subjugates the agriculture and domestic food markets of many developing countries and peripheral emerging ones that are undergoing rapid urbanization, to the needs of global agribusiness. For some of the larger developing countries, however, national compradore capital is also the principal force contributing to the emerging urban food crisis, by acting as or colluding with, Global North monopoly-capital. In addition, the state – through clientele capitalism and through government-linked companies (GLCs) – have also been playing a key role in the consolidation of the urban food system much to the insufficient stomachs of poverty poors, (read firestorm, 2021, Beefing Capitalism to sandwich Commodity Chains).

According to the World Food Summit, food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food.

Food security must be seen in terms of availability, accessibility, consumption and stability. Physical availability means that food must be readily available, while physical accessibility means the food must not only be available but people must also have access to it.

This comes at a time when world economic situation is expected to become more challenging in 2023 as energy crisis and food security are among the main economic threats, especially for developing countries, and even a developed country like Malaysia where agro-food import stood at RM$64 billion in 2022 or according to the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DoSM), imports of food accumulated to RM$482.8 billion over the last 10 years, while agricultural produce exports amounted to mere RM$296 billion.

With metropolitan corporate capital and its agribusiness entities owning and controlling the agriculture and domestic food markets of many developing countries, the situation enables, and ensured, a socio-economic shift in lifestyles and food habits favoring the rise of convenience foods, which, in turn, stimulated the expansion and large-scale entrance of foreign corporations into the fast-food sector. The main input ingredients in this sector are the white meats.

Brazil and Argentina, together with Thailand, became major suppliers of animal feed and meat, particularly in the provision of poultry and pigs, thus giving rise to domestic agribusiness firms – Sadia and Perdigão in Brazil, the Charoen Pokphand Group in Thailand and Leong Hup, Malaysia, which have poultry farms spread across Southeast Asia.

Although Perdigão and Sadia remain leaders in the white meats sector in South America, presently there are other strong entries of TNCs – with Doux the leading French poultry producer, ARCO from Argentina, Cargill, Bunge, and most recently Tyson from the United States now accounting for more than 20 percent of Brazil’s exports in this sector.

In the 1990s, China encouraged transnational corporate investment in partnership with domestic firms. As a result, global players are now firmly in place in trading, food processing, and retail in China. The major global seed firms for examples: Monsanto, Dupont, Syngenta, and Limagrain – are nowadays involved in joint ventures with Chinese seed companies and research centers, too. Therefore, with new regional actors emerging, the traditional global traders have successfully repositioned themselves around the new Southern Cone-China axis.

Increasingly, there is an indication of a long-term trend toward reproduction of the oligopoly pattern in agribusiness structured along the United States and European financialisation capitalism mode on a global scale.

A good example of the trend towards total control in the commodity supply chain is COFCO. This leading international, China-based agribusiness has acquired companies abroad, such as seed providers and agricultural trading corporations, to expand its control over the global supply chain. The company focuses on production of grains, oilseeds, and sugar and invests heavily in markets where there is potential for growth in these food items.

For example, COFCO acquired a leading seeds manufacturer in South America (Nidera) and a major food processing and trading company in Singapore (Noble Agri). As a result, COFCO has expansive control over the supply chain, all the way from sourcing and production to transportation and distribution.

Clearly, it is not a viable path for the many smaller countries across the world that are too small and too poor to compete on this basis.

The issue of economic power and concentration in monopoly-capital systems is thus would remain a vital concern of non-government organisations, labour movements and trade unions, and the green left on the financialisation of capitalism in the global agribusiness.

You must be logged in to post a comment.