05/03/2023

The revised Budget 2023 is – after a prolonging duration encasted in a stagnated economy deficit in structural reforms – on a better focused approach to restructure the State of Nation economic development path by way of applying the Madani Malaysia ethos.

What had been lacking through +6 decades in the economic development of the country is not due to lack of the vision or mission goals, but the inappropriate deployment of resources and the mishandling of allocated resources, overlaid by the socio-anthropological dimension with the burden of privileges that pulled back nation’s growth trajectory.

Glaringly, the civil service servants had been the dreadlocks that entangled the national productivity, then coupled with the trials of systemic odious practices – often enabled and or connivance with public service elements – have hung-dried an Asian tiger, (read STORM 2023, Place, Position, Power of Public Sector).

To revisit 2010, when trying to meet the growth targets of the 10th Malaysia Plan, “it would require a significant rise in productivity and investment,” so said Philip Schellekens, lead author of the Malaysia Economic Monitor, (World Bank, 2010).

“The dual approach in the Economic Transformation Program of combining cross-cutting policies with private sector-led projects provides an excellent platform. The proof of the pudding, however, will be in the consistent execution of policy reforms,” he said. “Also, until solid implementation of policy reforms is seen there is unlikely to be a groundswell of positive sentiment of foreign investors towards Malaysia.” (World Bank 2010, ibid).

Also, while trying to achieve Malaysia’s Vision 2020 goal of high-income status, at that moment of an era, would require “a higher growth rate than that achieved in recent years,” so said World Bank Sector Director for Human Development, East Asia & Pacific, Emmanuel Jimenez,

“the (other) challenge is also to ensure that the benefits are broadly shared across all layers of Malaysia’s society. While Malaysia has made truly impressive reductions in poverty, inequality persists at high levels.” (read further on race, class, poverty and inequality in malaysia new left, 2021).

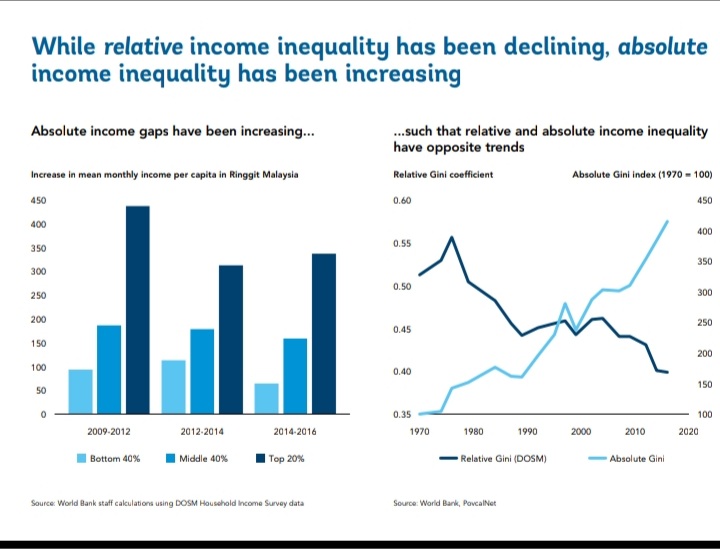

After six and half decades of sustained neoliberalism economic developmental effort, the nation of Malaysia is still as accentuated in absolute income inequality as ever, (see lower right chart below)

Sources: World Bank datasets and DoSM statistics

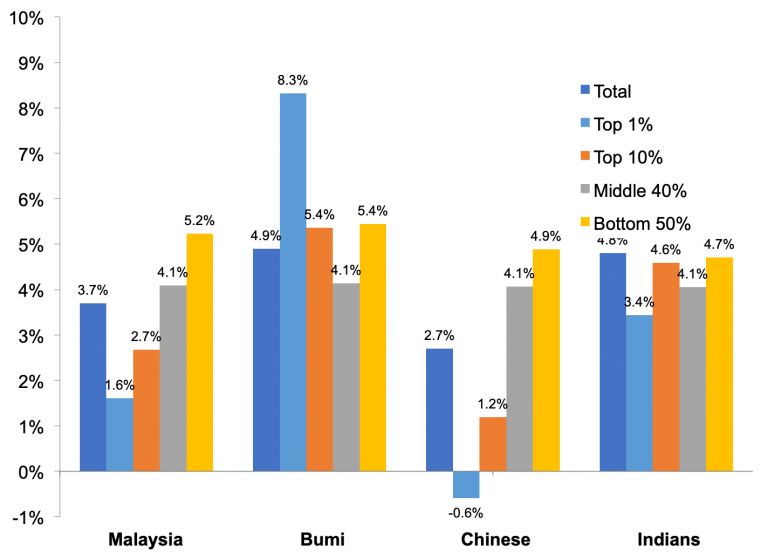

Further expressing that “The bulk of inequality today can be explained by differences in socio-economic factors within ethnic groups rather than differences across groups. It is time to bring all Malaysians within the ambit of greater economic opportunity.”

This is ardently expressed by Khalid research paper at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where presented, the disparity among the Malay community – the top 1% – is much acute, and accentuated:

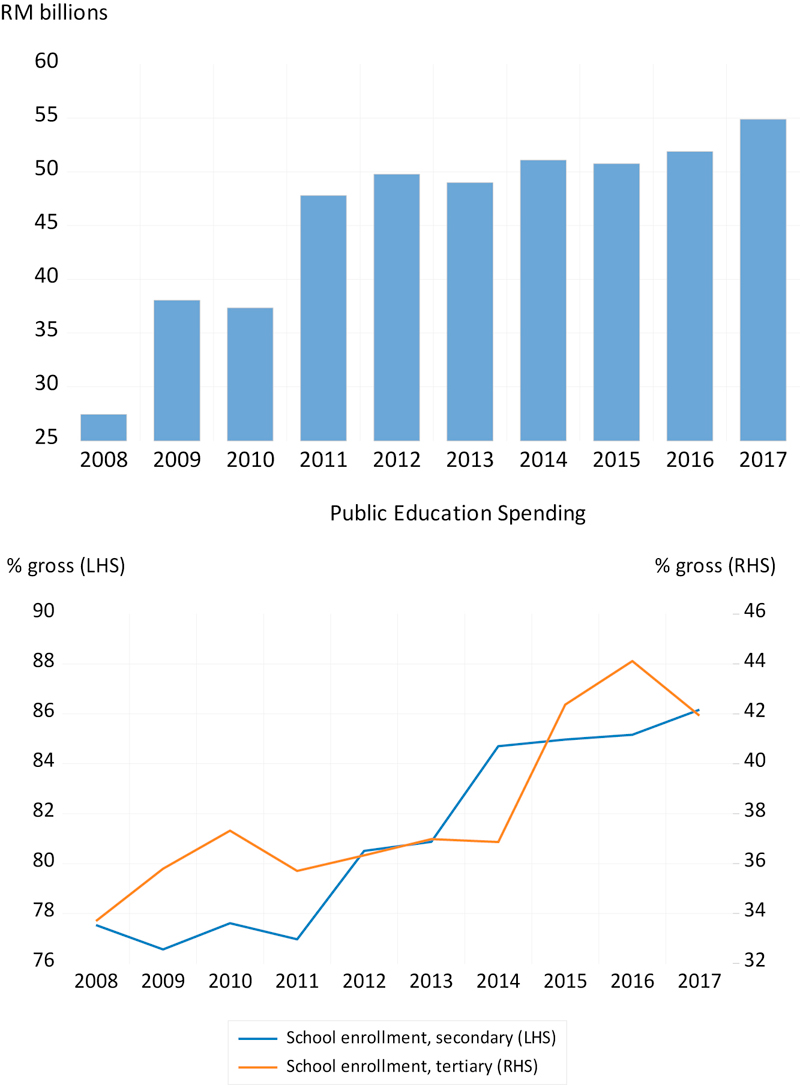

Some had articulated that it is the faulty education ecosystems, but while many Malaysians cannot take advantage of income-earning opportunities because they lack the skills to do so, then, despite massive investments in education, for many others, skill needs have changed more quickly than the availability of educational and training opportunities.

It begins to dawn to policy-implementors that as Malaysia seeks to increase knowledge and innovation in its economic activities, it is even more important not to marginalize the unskilled workforce who more likely than not is categorised under as underemployment and or performing zero-hour activities in the gig-economy with all attributes of extractive surplus value being emphasised, and endorsed within a capitalism praxis.

We seems to be living in an era not dissimilar to imperial ownership and control where wage growth remains very low while capital maximized investment returns through extracting surplus-value from labour.

The widening of absolute income gaps between the bottom 40 percent and the top 20 percent of the income distribution have only furthered the angered sentiment of being left behind.

Therefore, in complementary to education is the necessity of labour market reforms that raise the level of employment, streamline the regulatory environment for businesses and remove barriers for new investment.

However, even if income-earning opportunities exist and access to labour, it is still broadly inadequate because some Malaysians will inevitably remain excluded or require temporary support.

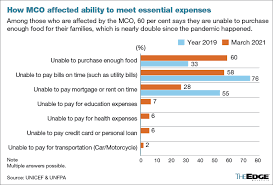

Thus, though important elements of a social protection system are in place in Malaysia, there are still many significant gaps remaining – distinctively displayed during the Covid-19 pandemic when income disparity within populace was further accentuated.

It was also a time when 70% of lower-income households cannot even meet monthly basic needs – indeed, more than 60% of these households reported having no savings at all – not much of a difference than 10 years ago:

and where these household expenditures are expansively spent on food:

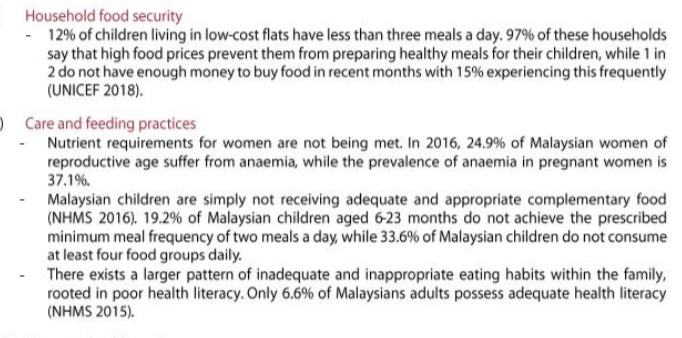

But, not every poor, even urban, household has all the requisite food nor valued nutrients (UNICEF 2018):

In the study, Children Without – A study of urban child poverty and deprivation in low-cost flats in Kuala Lumpur, UNICEF unearthed:

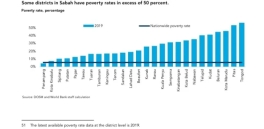

Further, the state of Sabah gross domestic product per capita of RM5,745, compared with the national average of RM7,901, (read csloh , Sabah – a state underdeveloped) where the Borneo state’s poverty rate is three times that of the national average, and there is a high degree of inequality across districts, too:

After six and half decades of sustained neocolonial economic developmental effort which is nothing but underdevelopment under neoimperialism, the nation of Malaysia is still casted in acutely absolute income inequality as ever:

One way out of this continous poverty trap is that social safety net programs should be more poverty-focus, targeting mechanisms have to be improved and fragmented programs could be replaced by a well-coordinated social protection system, (see Malaysia Economic Monitor, November 2010 – Inclusive Growth).

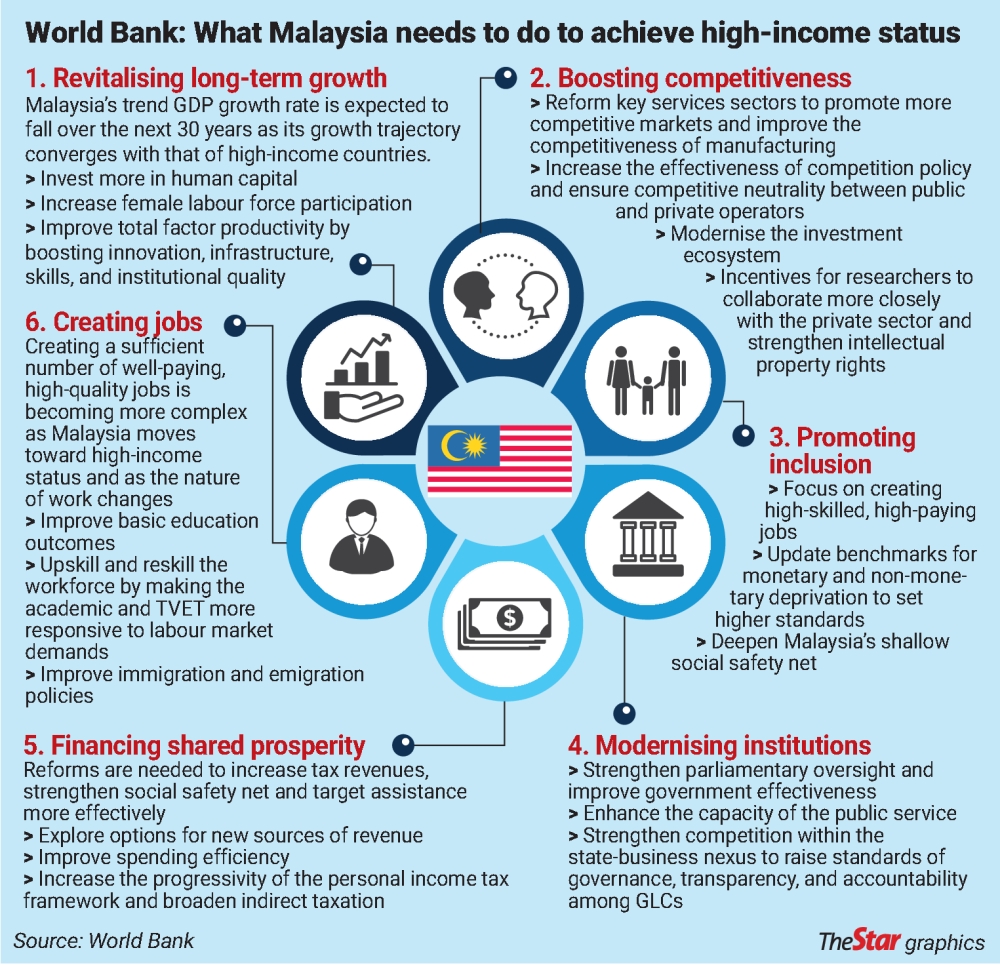

Indeed, in the subsequent World Bank Report 2022, the social safety net resurfaced whereby the agency again with an urgency recommended that:

In the short term, financial support for the poor and vulnerable should continue. This includes a more inclusive social insurance framework with improved targeting. The continuation of cash assistance programs to support financially disadvantaged households will provide safety nets and much-needed protection from economic shocks.

The subsequent subsection is a Creative Commons reposted blog by PHILIP SCHELLEKENS, November 08, 2010, where he argued

Why Updating Malaysia’s Inclusiveness Strategies is Key

Compare South Korea and Malaysia in 1970 and compare them again in 2009. South Korea was a third poorer back then and is now three times richer. Even more remarkable has been South Korea’s ability to widely share the benefits of this spectacular feat across broad segments of society. South Korea’s strong focus on broad-based human capital development allowed the country to transform itself into a high-income economy, while at the same time reducing income inequality and improving social outcomes.

Malaysia’s inclusiveness strategies have produced some remarkable successes as well. Malaysia dramatically reduced poverty and has all but eliminated hardcore poverty. But the country has been far less than successful in reducing income inequality which, since 1970, steadily fell for two decades but has stagnated at high levels ever since. The last two decades also saw Malaysia’s growth model of high-volume low-cost production being challenged. Economic powerhouses emerged in the region, which led to more intense competition for talent, trade and FDI. For Malaysia to remain competitive, it became clear that it needs to compete on value, not cost, and this requires a refocusing on getting the incentives right for innovation, creativity and entrepreneurship.

The comparison with South Korea is partly flawed and unfair. For one, South Korea did not need to manage the ethnic tensions Malaysia was facing given the differences in demographic make-up. Also, South Korea was clearly an exceptional success story that few countries around the world have been able to replicate. On the flipside, Malaysia’s economic performance cannot be underplayed either. Indeed, the Commission on Growth and Development identified Malaysia as one in only 13 countries around the world that has since 1950 registered over a period of 25 years or longer an average growth rate of more than 7 percent.

Leaving these caveats aside, the sheer difference in growth performance, as well as South Korea’s remarkable success in improving social outcomes, is nevertheless instructive. The comparison offers some insights on what Malaysia could have achieved, andmore importantly can achieve in the future. This characterization also lies at the core of the recent self-diagnosis undertaken by the Government of Malaysia. The New Economic Model, the Tenth Malaysia Plan and the Economic Transformation Programme all speak to the need to update Malaysia’s inclusiveness strategies so as to realign them with the objective of becoming a high-income economy.

The need to update Malaysia’s inclusiveness strategies reflects both new realities and new challenges. The new reality is that poverty is no longer the key issue when thinking about inclusive growth. Poverty still exists—and pockets of poverty remain deep and concentrated—but inequality is now in the spotlight and is presenting a tremendous challenge. The other new reality is that inequality is no longer what it was four decades ago. Nowadays over 90 percent of the level of inequality is explained by differences within ethnic groups rather than differences between these groups. Individual socio-economic characteristics, such as activity status, sector of employment, urban versus rural stratum, and educational attainment are now the capital explanatory factors, no longer ethnicity.

Malaysia’s high-income aspiration is also raising a whole new set of challenges. High-income economies tilt the demand for labor in favor of the skilled, sharpening income inequality across the skills spectrum. They tend to specialize in product niches and concentrate activity in narrow geographical clusters, raising challenges to retrain people and move them around to where the new jobs are. They are also open to competitive forces, creating challenges for those who are unable to compete or unlucky as a result of such competition.

The November 2010 issue of the Malaysia Economic Monitor, which we are publishing today, offers an analysis of where Malaysia is today and where it could go tomorrow by updating its inclusiveness strategies. Our recommendations on this highly charged topic do not come out of the blue—they are based on a detailed analytical study of the latest household income, labor force, and enterprise surveys, which the authorities have made available to our team. We are also leveraging on the experiences of other countries around the world, who have addressed or are coping with similar challenges.

To fast-forward to the 2023 World Bank’s Malaysia Economic Monitor where the agency is strongly advocating digitalization of a new economy frontier (though critiques are that neoliberalism is modern imperialism assuming a new identity) promoting infrastructural platforms to cater for Global North monopoly-capital, but even then, there are resource limitations and social constraints that could, again, likely pull back the country’s ability and capacity to progress; simplified, it is primarily due to:

a) The lack of financial resources and digital skills have been cited as key constraints towards digitalization;

b) Even smaller formal firms relied on more traditional methods of payment, especially cash; and

c) Vulnerable segments of the population remain unbanked, despite the expansion of digital financial services.

These other matters pertinent to the national digitalisation process and an e-commerce economy shall be explored, and be expanded, in subsequent articles with differential dimensional approaches recommended to be undertaken when aiming for The Big Push.

Pingback: M137 4th – 10th March 2023 – MOMENTUM

Pingback: SATURDAY SURGE:11/03 – MOMENTUM