28/03/2023

1] INTRODUCTION

TnG is currently the only contactless and cashless method of payment at highway tolls and for public transport in the country. Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim said on 19th March 2023 the monopoly of TnG would be reviewed so that other forms of toll payments could also be used.

On the following day, Transport Minister Anthony Loke said an open payment system for transport services under Prasarana Malaysia Berhad would be implemented soon to give public transport users other choices besides TnG.

Aside from TnG, there is a monopoly for motor vehicle inspection (Puspakom Sdn Bhd), landline telecommunications (Telekom Malaysia Bhd or TM), electricity supply (Tenaga Nasional Bhd or TNB), SYABAS Selangor sole water supplier, and the medical supplies to government hospitals, (Pharmaniaga Bhd), and Bernas – the rice importing entity controlled by Syed Mokhtar Albukhary, preceeding regimes’ profit-gaining prodigy.

Then, there is at least one case of a very limited competition – that of the import of sugar. The business is controlled by only two companies, namely, MSM Malaysia Holdings Bhd and Central Sugars Refinery Sdn Bhd. Individually, the market capitalisation of these companies ranges from RM$629 million to RM$19.95 billion.

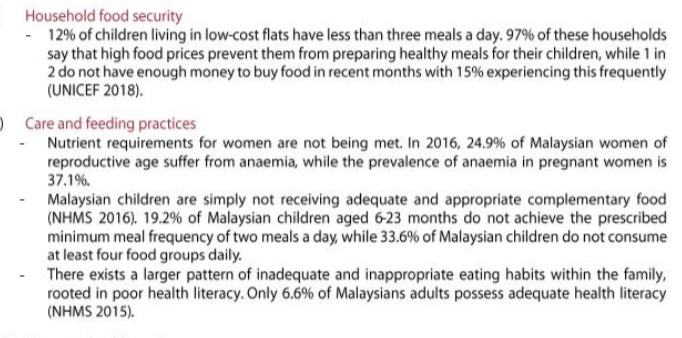

Geoffrey Williams of the Malaysia University of Science and Technology had said monopolies in food production, especially in the import of rice and other staples, that should also be dismantled as they led to higher prices for consumer besides introducing food insecurity in the country.

Those are positive suggestions in breaking commodity and service monopolies in Malaysia. The dismantling of the monopoly in the food and essentials sectors to ensure competition is a good direction to end ruthless profiteering through sheer capital accumulation in clientel-rentier capitalism that reeks of inequality and marginalisation, (read STORM, March 2023, Structuring Sustainability in Economic Development).

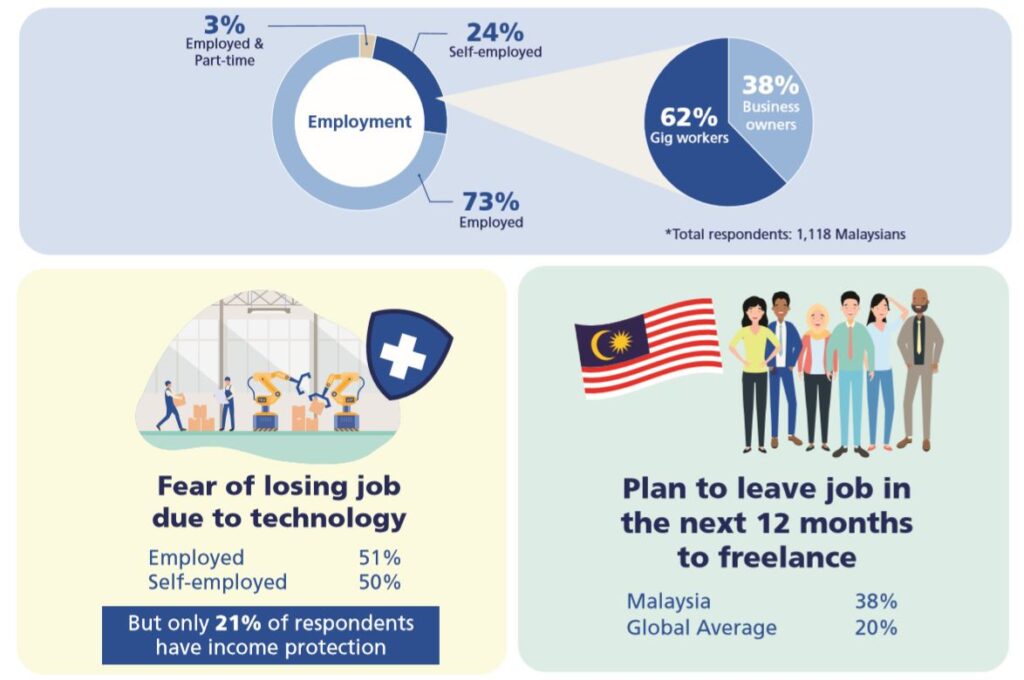

It has reached a phase whereby capitalism genesis new formation in search of economic exploitative relations, subjecting exploited labour to monopoly-capitalised control. The terrains of economic territory that are increasingly subject to capitalist organisation and monopolistic penetration are in basic amenities and social services that used to be the sole preserve of public provision. However, the generation and distribution of knowledge under the dominant domain of infrastructural platforming ecosystems, (read STORM 2023, Techno-feudalism), has induced the gig-economy labour dimension as digitised digits, (STORM 10/03/2023, Short-circuiting the Rakyat).

2] CAPITALISATION OF CONTROLLED RESOURCES

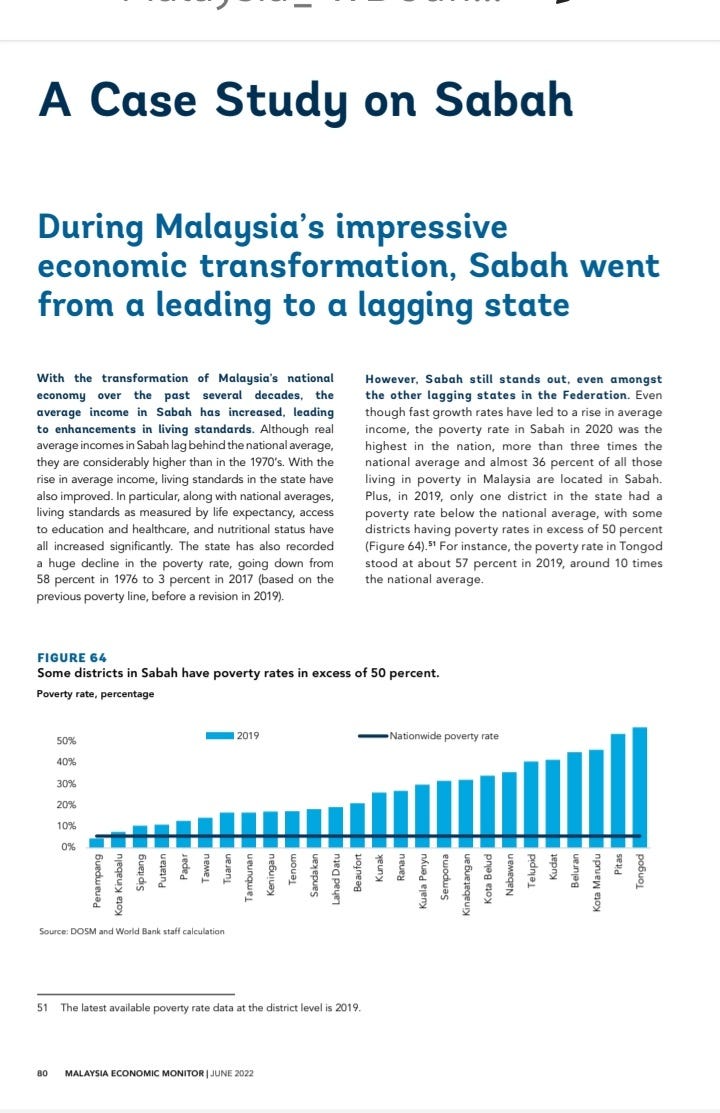

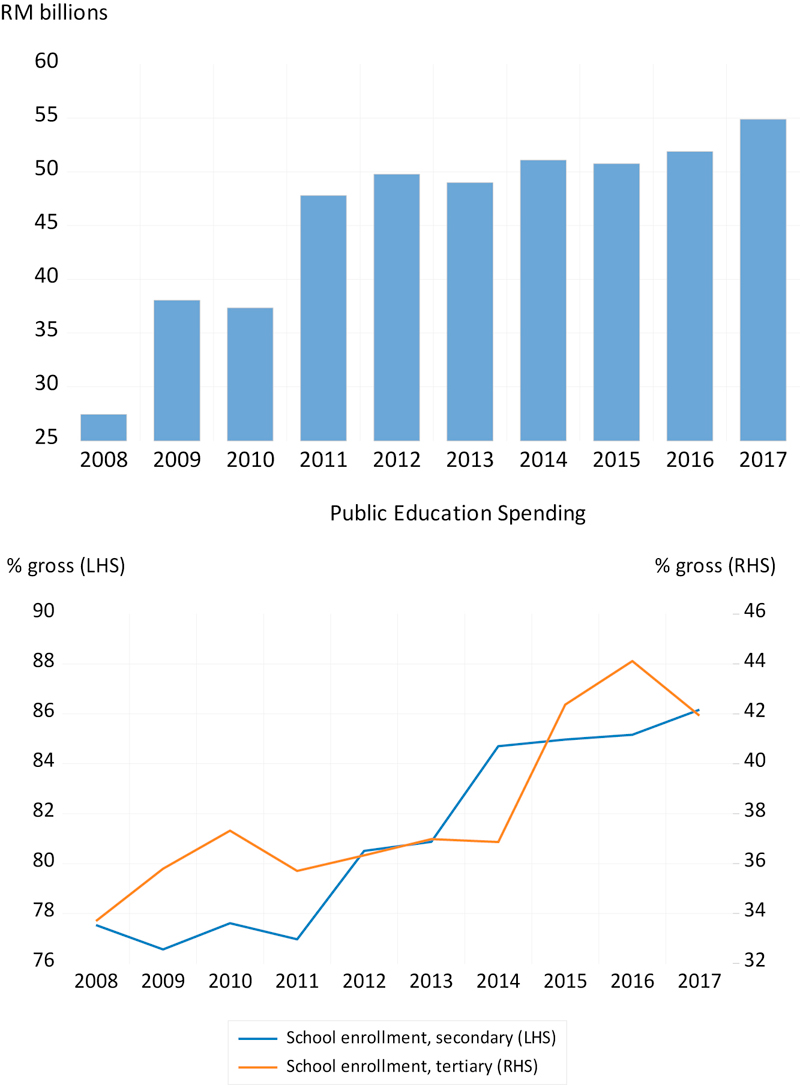

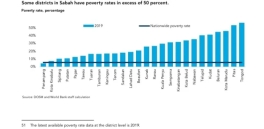

A major feature of our times is the privatisation of much of what were generally accepted as basic responsibilities of public provision. Basic amenities like electricity, water and transportation infrastructure, and social services like health, education, water and sewerage sanitation used to slot into this category. Of course, the fact that these were seen as public duties does not mean that they were always fulfilled – just look at the slacking educational segment with its inadequate deliverance, (csloh, Sabah – a state underdevelopment).

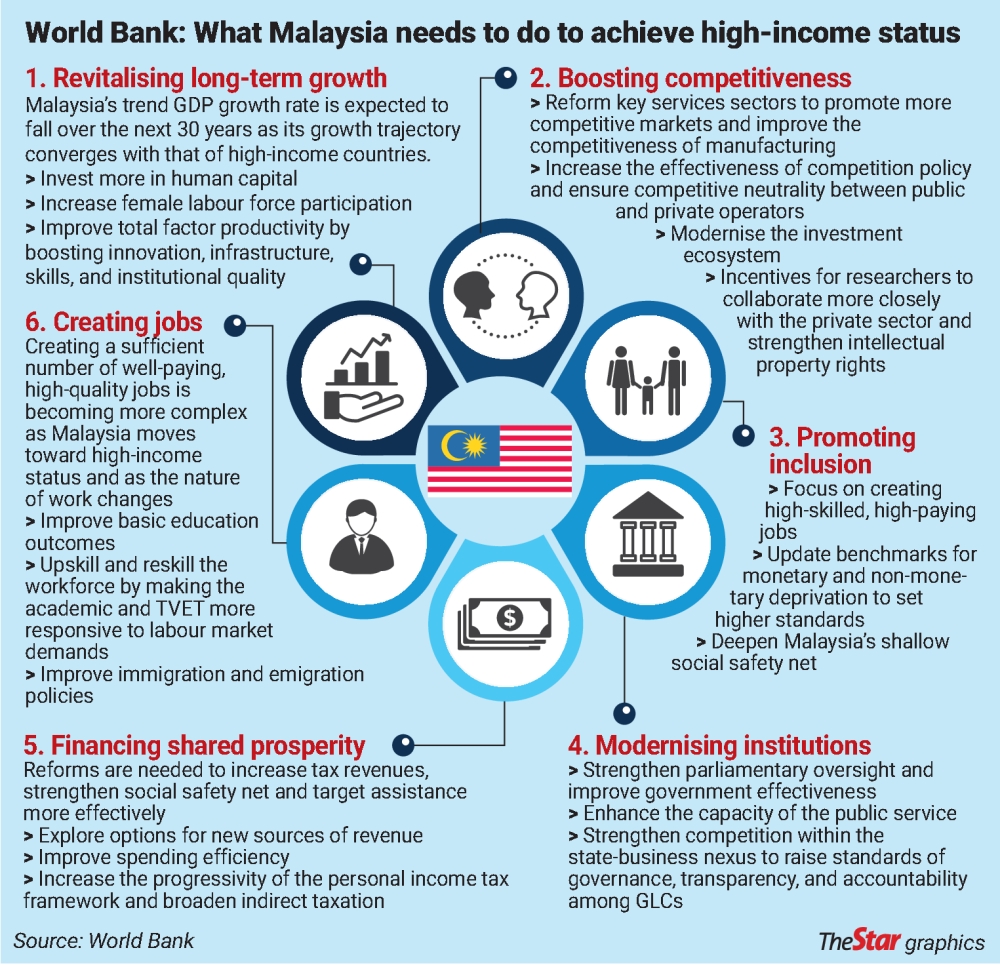

That private provision has increasingly opened up huge new markets for potentially profit-making – and capital accumulation to clientel-capitals’ related activities. Given the saturation of markets in many mature economies, and the inadequate growth of markets in poorer societies, and the intrusion of global institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization (WTO), as well as more informal bodies such as the World Economic Forum that have actively encouraged private investment in formerly public sectors.

Simplified, these entities are more an expression of the modern imperialistic drive for control over economic territory than the neocolonial direct annexation of geographic territory, but that does not make it any less consequential.

As an instance, the privatisation of knowledge and its concentration in fewer and fewer hands – especially through the creation and enforcement of new ‘intellectual property rights’ – have become significant barriers to technology transfer and social recognition of traditional knowledge. This is clearly evident in the case of access to medicines whose prices have been hiked up by patents that reward multinational companies and allow them to monopolise production and set high prices or demand very high royalties.

Similarly, control over seed patents, which are overwhelmingly held by TNCs (transnational corporations), have enabled Big Agribusiness monopoly control over crucial technologies for food cultivation across the world, even in the poorest societies, (STORM 2023, Agribusiness and food insecurity).

Further, for industrial technologies, as well as knowledge for mitigating and adapting to adverse environmental changes – they are all grave ecological disasters from the production systems created by global capitalism.

Meanwhile, at the production phase, from which workers and small producers like SMEs mainly derive their incomes, is exposed to cut-throat competition between different production sites across the world in the globalisation trend to “liberalise trade”. Consequently, incomes generated in this stage of the value chain are kept low through the mechanism in global labour arbitrage.

The overall result is twofold.

First, this situation results in an increase in the supply of the ‘global’ labour force (workers and small producers who are directly engaged in production of goods and services).

Second, the power of corporations to capture rents – from control of knowledge, from oligopolistic or monopolistic market structures, and from the power of finance capital over state policy – has greatly increased, (STORM, 2021, Dominance of financial monopoly capitalism).

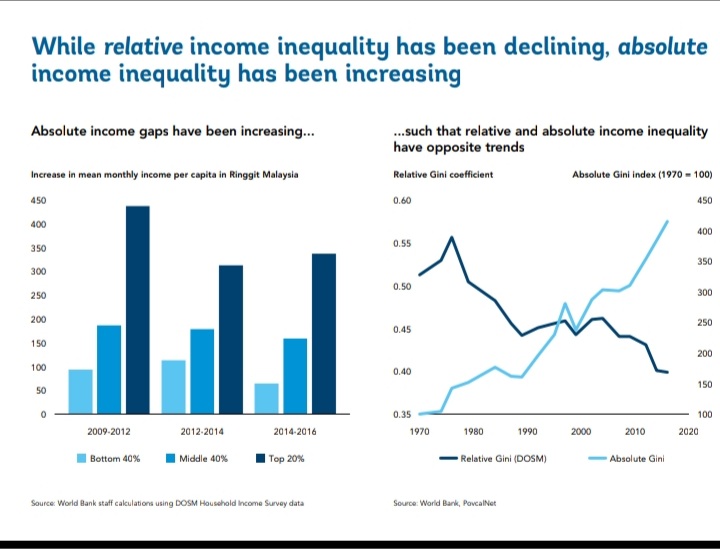

Overall, this has meant a dramatic increase in the bargaining power of capital relative to labour, which in turn has resulted in declining wage shares (as a percentage of national income) in both developed and developing countries. These processes have only worsening material conditions for many workers in both the periphery and the core.

Imperialism has inadvently weakened the capacity for autonomous development in the Global South, and worsened economic conditions for workers and small producers in the emerging and low-income countries.

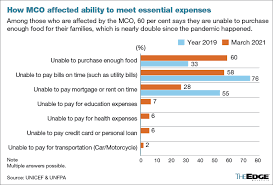

In April 2022, Oxfam reported that more than a quarter of a billion people falling into extreme levels of poverty in 2022 alone.

In its January 2021 Report, ‘The Inequality Virus’, Oxfam stated that the wealth of the world’s billionaires increased by US$3.9tn between 18 March and 31 December 2020 when their total wealth stood at US$11.95tn, a 50 per cent increase in just 9.5 months.

Further, according to Oxfam’s analysis, 13 out of the 15 IMF loan programmes negotiated during the second year of COVID required new austerity measures such as taxes on food and fuel or spending cuts that could put vital public services at risk. Indeed, Oxfam and the Development Finance International (DFI) had revealed that 43 out of 55 African Union member states face public expenditure cuts totalling US$183 billion over the next five years.

The world’s poorest countries were due to pay $43 billion in debt repayments in 2022, which could otherwise cover the costs of their food imports.

Remembering that beneficiaries had intensified during the global boom of the 2000s, when median workers’ wages stagnated and even declined in the Global North metropolitans even as per capita incomes soared. However, those increases in income were only captured by stockholders, corporate barons and financial rentiers and capital vultures.

Therefore, from a bigger picture perspective, we are witnessing even in the rich countries with glaring evidence, increasing inequality, stagnant real incomes of working people, and the increasing material fragility of daily life have all contributed to a deep dissatisfaction among ordinary people, (Oxfam Report 2022).

3] MONOPOLY-CAPITALISM

Monopolies do not exist by themselves. These entities existence owes systemic institutionalisation of politico-economic policies of preceeding regimes that introduced ethnocratic kleptocrats’ practices which encouraged illegal trading and odious transactions.

As part of the neoliberal globalised economy – where 40% of labour are involved in international trade – the country spawns intermediaries as comprador capitalists to cooperate, collaborate and collude with Global North monopoly-capital mission objectives.

Monopolies technology founded by the infrastructural platforms of the imperialist centres; the monopoly of access to natural resources like those in the Big Agribusiness sector; the monopoly over finance as dominated by foreign banks; the monopoly over international communication and the multimedia in fibre optics installation and maintainable by the infrastructural platforms monopoly-capital – all these demons affect a national economic development.

These monopolies tend to be regionally concentrated in the countries of the Global North, but since the globalisation trend in the 1970s also persist in a more multipolar world with peripheral subsidies emerging in the Asia-Pacific, South America and Middle East and North Africa (MENA) regions.

The resultant image of monopoly-capital is

identifiable according to Samir Amin and Jayati Ghosh in Interpreting contemporary imperialism: lessons from Samir Amin,

to six significance categories:

(1) the imperialist bourgeoisie at the centre or core, to which accrues most of the global economic surplus value;

(2) the proletariat at the centre, which earlier benefited from being a labour aristocracy that could enjoy real wage increases broadly in line with labour productivity, but which was now more threatened and experiencing falling wage shares and more insecure employment conditions;

(4) the dependent bourgeoisie of the periphery, which exists in what he saw as an essentially comprador relationship with multinational capital based in the core; possible a higher rate ofaccumulation.

(5) On the demand side of the accumulation equation, monopolistic industries adopt a policy of slowing down and carefully regulating the expansion of productive capacity in order to maintain their higher rates of profit.

The consequences of monopoly mean that the savings potential of the system is increased, while the opportunities for profitable investment are reduced. Other things being equal, therefore, the level of income and employment under monopoly capitalism is lower than it would be in a more competitive environment.

(6) the proletariat of the periphery, which is subject to super-exploitation, and for whom there is a huge disconnect between wages and actual productivity because of unequal exchange;

(5) the peasantries of the periphery, who also suffer similarly, and are oppressed in dual manner by pre-capitalist and capitalist forms of production; and

(6) the oppressive classes of the non-capitalist modes (such as traditional oligarchs, warlords and power brokers).

While the global supply chains represent the integrative structure of contemporary global capitalism, and any disruption to them potentially threatens the functioning of the system itself, present discourses from policymakers seem to be, and keen, to promote their purported benefits, that is, proposing multifaceted ways to increase supply chain “resilience.” (IMF 2023).

This articulated notion has been defined by the World Trade Organization and Asian Development Bank as “the ability of these chains to anticipate and prepare for severe disruptions in a way that maximizes capacity to absorb shocks, adapt to new realities, and re-establish optimized operations in the shortest possible time.”

While global supply chains are promoted as generating positive gains for firms and workers, North and South there is mounting evidence to suggest that they represent organizational forms of capitalism designed to raise the rate of surplus value extraction from labour by capital and facilitate its geographic transfer from the Global South to the Global North.

As global supply chains have contributed to dynamics of concentration in leading firms, there is emerging a marked shift in national income from labour to capital across much of the world, (read Monthly Review, 2021, Breaking the Glass Screen – Framing Monopoly Capitalism in Global Commodity Chains.

Capitalism, as Karl Marx observed, is rooted in the exploitation of labour by capital through the latter’s ability to extract surplus value from the former.

It is characterized by dynamics of concentration and centralization of capital, where fewer and larger firms increasingly dominate each economic sector.

These dynamics are intrinsically related to capitalism’s uneven geographical development and the reproduction of geopolitical tensions and geoeconomic disruptions.

References

An overall excursion with a better understanding of monopoly-capital and capitalism can be acquired through these related readings:

Benjamin Selwyn and Dara Leyden, “World Development under Monopoly Capitalism,” Monthly Review 73, no. 6 (November 2021): 15–28.

Intan Suwandi, Value Chains: The New Economic Imperialism (New York: Monthly Review , 2019).

John Smith, “The GDP Illusion,” Monthly Review 64, no. 3 (July–August 2012): 86–102.

John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, and R. Jamil Jonna, “The Internationalization of Monopoly Capital,” Monthly Review 63, no. 2 (June 2011): 1.

John Bellamy Foster, and Intan Suwandi, “COVID-19 and Catastrophe Capitalism,” Monthly Review 72, no. 2 (June 2020): 1–20.

and

STORM, 01/06/2021 Framing Monopoly-Capitalism

STORM, 05/03/2021 Capitalism

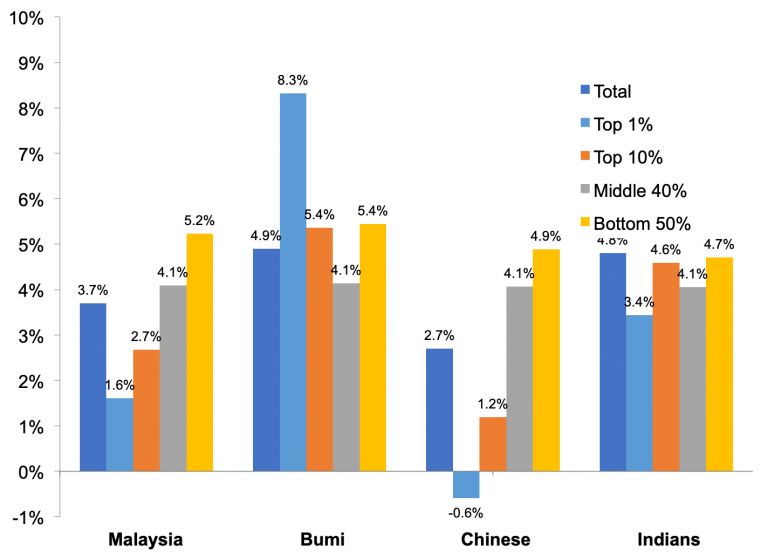

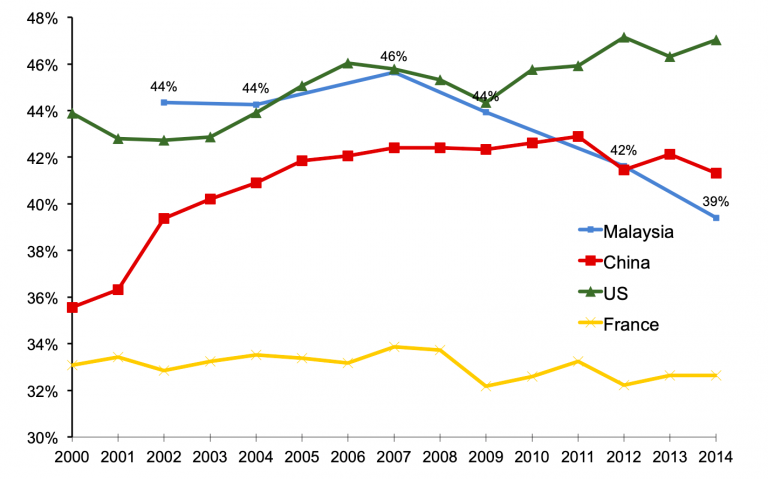

Notes: Distribution of pretax national income (before all taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two). Imputed rent is included in pre-tax fiscal income and pre-tax national income series; source:

Notes: Distribution of pretax national income (before all taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two). Imputed rent is included in pre-tax fiscal income and pre-tax national income series; source:

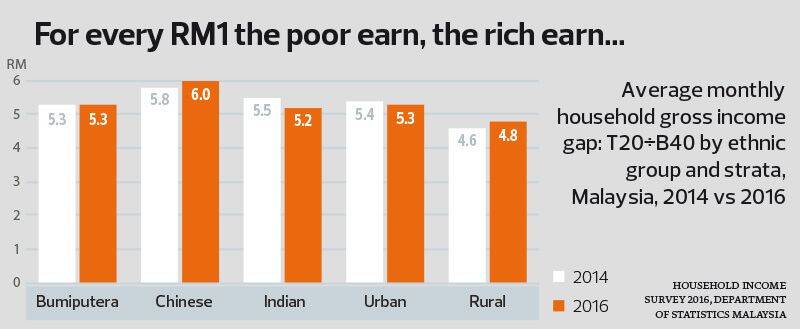

Malaysia’s 50 Richest 2020;

Malaysia’s 50 Richest 2020;  Source:

Source:

You must be logged in to post a comment.