12/03/2023

1] The ECONOMY SPREAD

After 6-decade plus in “economic development “, the state of a nation is still mired in poverty stretching from north and northeast semanjung across the South China Sea to the Borneo states of Sarawak and Sabah:

Indeed, the poverty rate in Sabah in 2020 was the highest in the nation – more than three times the national average. That 36 percent of all those living in poverty in Malaysia are located in Sabah only emphasized the development of a underdevelopment in a natural resource-rich state with oil and timber. Sabah had a gross domestic product per capita of RM5,745, compared with the national average of RM7,901, (read csloh , Sabah – a state underdeveloped).

By 2019, many districts in the Sabah state were in poverty rates in excess of 50 percent.

As an instance, the poverty rate in Tongod stood at about 57 percent in 2019, around 10 times the national average.

Even within an urban setting, in the study, Children Without – A study of urban child poverty and deprivation in low-cost flats in Kuala Lumpur, UNICEF unearthed:

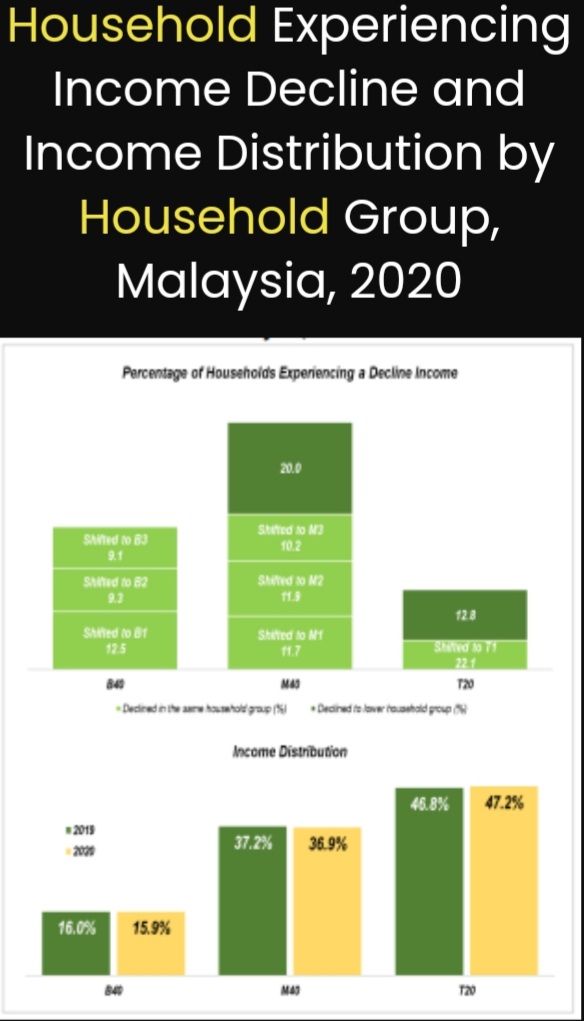

When we have 70% of lower-income households that cannot even meet monthly basic needs – indeed, at least 86% of these urban households reported having no savings at all – not much of a difference between them and their rural community folks:

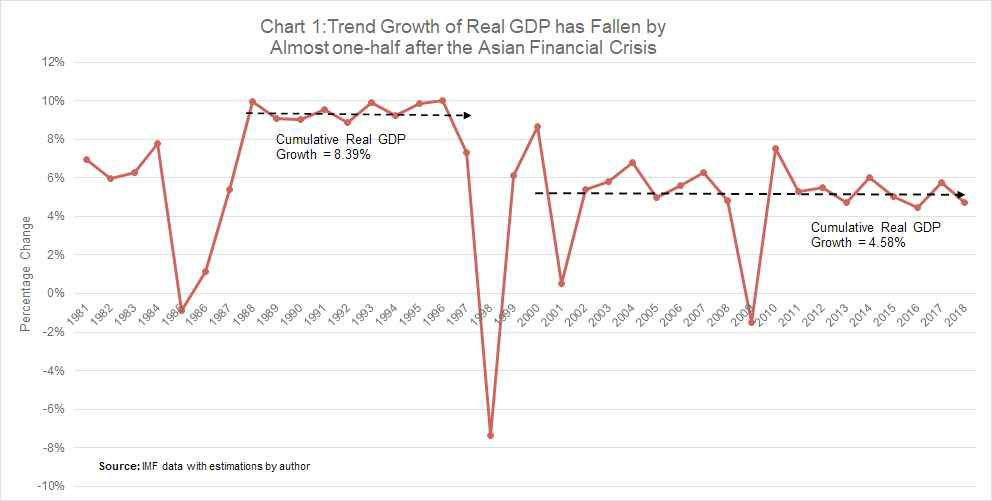

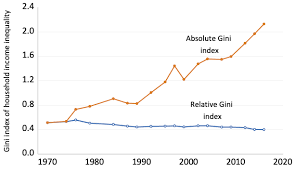

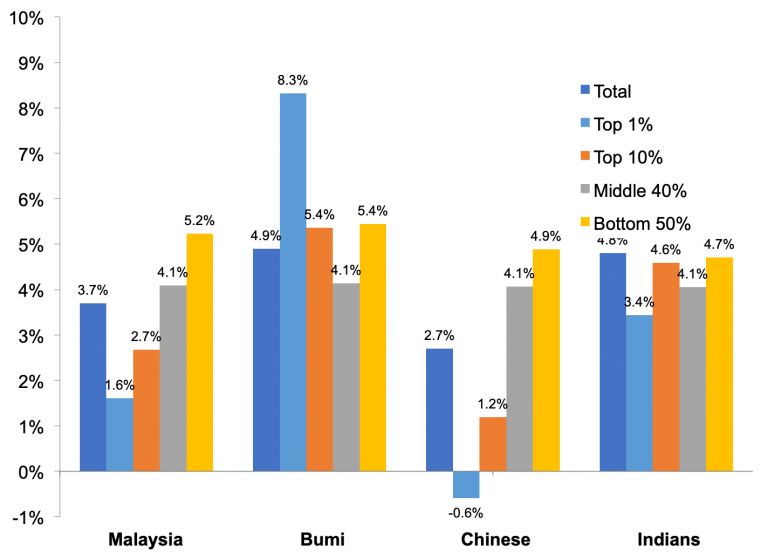

At the macro-level, the country is in a slow growth regime

where any incremental growth will depend less on factor accumulation, but more on raising productivity – which over the past 25 years has been below that of several regional comparators – to sustain higher potential growth.

Coupled with the premature de-industrialisation in the 1990s – where 40% of work force are contributing, directly and indirectly, to the manufacturing exports sector then – it is not surprising that the poverty rate has not only risen, but disparity has accentuated

2] The TAPAO

The targeted area-based poverty alleviation objectives (TAPAO) are to adopt instruments from nationwide approaches to provide basic relief to broaden targeted interventions regionally; followed by more narrowly focused programs for poor district areas, daerah², and villages kampung²; and finally with measured activities targeting specific poor households directly.

Concurrently, to be successful – maintainable and sustainable – the coverage of social protection programs have to be rapidly expanded, too.

Briefly, this area-based development-oriented poverty alleviation efforts have to be structured with a national-wide Poverty Reduction and Extra-Developmental Initiative Schema (PRAXIS) as the immediate response to lagging economic growth and stagnating incomes in the identified areas of the country. Whether a State Economic Development Corporation’s Poverty Reduction and Development group is to be established “to provide coherence to a large number of poverty reduction initiatives and, in particular, expedite economic development in poor areas” (as advised by World Bank 2009, for another country) or that The PRAXIS shall identify poor daerah, primarily based on district-level average rural per capita income that must also focus on the mountainous hinterlands of the country, especially in Sarawak and Sabah.

Refining the geographical target of poverty reduction programs is a necessity. The TAPAO needs to shift from daerah² to kampung² including more likely

some outside the list of poverty-stricken daerah, too. Collectively, those designated kampung² (villages) may cover

a certain high percent of the country’s rural poor. Designated villages could then apply for projects to support local production and infrastructure (including makanan-dengan-kerja programs, worker training,

and agribusiness development comprising technology extension services; not to be neglected, government-linked investments in social infrastructure (schools, clinics, community and recreation centers), with a particular strong participatory gotong-royong approach.

Whatever the developmental programs to be formulated, development of farm

activities and off-farm employment opportunities (funded with subsidized loans); infrastructure

development in roads, electricity, and safe drinking water using predominantly rural workers on the basis of

food-with-work (makanan dengan kerja); a comprehensive universalisation of primary education and basic preventive and curative health care that is community-based; establishment of a monitoring system – very importantly – to hold local personnel in governance accountable for the use of budgetary transactions; and the mobilization of a broad group of government and nongovernment

actors in a joint poverty reduction effort.

Poverty is one of the key factors of education inequality in the country, (World Bank, 2022; and World Bank,2019). On top of the disadvantages of the rural urban disparity, students in rural communities tend to come from a lower socioeconomic class as compared to their urban counterparts; and these inadequacies permeated across states, too, where in Sabah and Sarawak there are high numbers of children between 5 and 19 years old who have no schooling

3] THE STRATEGIC WRAPPING

The targeted poverty alleviation strategy should be aimed to help all of the poverty poors to achieve incomes above the national income poverty line and meet a set of multidimensional goals.

The strategy should span the arching process from poverty identification to poverty exit, determining whom to help, who should help, how to help, how to exit, and how to avoid poverty reoccurrence.

The strategy has to be based on a comprehensive database of targeted households and their specific needs, complemented with local knowledge to find appropriate solutions, and importantly, from past experience in odious practices, the definition of clear lines of accountability for optimal results.

It needs to be said that instruments that should be deployed would include policies for economic development and income generation, relocation and resettlement, ecological protection and ecology disasters compensation, education, and social protection. The overall strategical aspects would overall remained focused on creating the conditions for poor households to find employment and a stable source of income to lift themselves out of poverty, while combining this with household-specific support in key areas such as rural settlements and urban housing, skills enhancement and development, health care, job search, and where necessary, income transfers including unit-trust investments and savings.

The identification of poor households would be that of an integrated top-down and bottom-up approaches. The top-down approach included the Department of Statistics, Malaysia (DoSM) – whose dataset would determine “numerical quotas” of poor households, both nationwide and in each daerah-district refering to the 2022 national poverty census as a baseline for bottom-up identification. The quota parameters should be broken down to each administrative level. Under the bottom-up approach, civil service officials and student-recruited census interviewers are to be dispatched to carry out precise poverty identification data collection.

On the basis of the quota allocated, each team registered every poor household regardless of whether they live in the poor district or daerah.

It has to be stated that notably, household income ceased to be the only criterion for identification. At times, most of the time, local government officials often do not have accurate and reliable income records for all rural households, thus they can adopt a different criteria such as verifying household assets like home and durable goods utilised to supplement the income-based poverty line.

Further, to include all qualified households, individual districts may be allowed to register up to 10 percent larger populations than their numerical quotas to obtain a better baseline.

The implementation of the strategy may not likely be smooth. Errors of inclusion (households identified as poor that did not need assistance) and exclusion (poor households that failed to receive adequate support) resulting from governance weaknesses in rural areas and mountain hinterlands may likely emerge, given the lack of reliable income survey data at the kampung-village level. This may eventually lead to additional verifications and the reidentification of poor households, as well as close supervision of declared “exits” from poverty.

It has to be further stated that local grass-root feedbacks may have to be created to support top-down accountability, too.

4] THE TAKEOUTS

TAPAO is appealingly appetising, but

A) TAPAO can only be tastefully successful if a nation is truly endowed with a “capable and effective government” (Bikales 2021; Ravallion 2009), as reflected in the ability to articulate credible policy commitments, to effectively coordinate decisions by various government departments, and to mobilize a variety of social actors to support a national goal.

It is acknowledged that a capable, credible, and committed government is key to the success of development strategies. The 2017 World Development Report (World Bank 2017) identifies the core functions of effective governance to draw lessons for development. Its main message is that effective governance institutions deliver three core functions: credible commitment, enhancing coordination, and inducing cooperation.

All three core functions were present in the design and implementation of China’s poverty reduction efforts, which represents an interesting case study of effective governance, (World Bank and DRC 2019).

First, the credibility of the government’s commitment to poverty reduction has to be flagged early on, with clearly defined targets and the creation of an entity like the Poverty Reduction and Extra-Developmental Initiative Schema (PRAXIS) to supervise progress and establish accountability at the highest level.

When, during this early process, if it becomes clear that economic growth alone would not suffice to reach the last mile of poverty reduction, there has to be a positive feedback in the form of learning, unlearning, relearning education (to LURE back dissidents or disruptive elements, whether in the targeted area-base residents or from governing civil servants).

Then, secondly, the Poverty Reduction and Extra-Developmental Initiative Schema (PRAXIS) coordinating supremo has to consolidate all federal ministries and departments, reflecting the importance placed on interdepartmental coordination and collaboration, though it is also preferable that local district officials are given wide latitude to experiment, and indeed, compete with each other.

PRAXIS, for instance, should embrace the quintuple helix approach where the State district officers mobilise the vital five subsystems (helices):

(1) education system,

(2) economic system

(3) natural environment,

(4) civil society

(5) and the political system

to not only articulating the objectives but also the inter-linkages in process, procedure and people elements in TAPAO deliverance.

Thirdly, through this defined administrative procedures, reward and accountability mechanisms, with a strong performance management system, shall ensure that civil servants aligned personal goals with central priorities on one hand and career promotion dependent on their performance in achieving predefined outcomes (for example, economic advancement, social stability, or poverty reduction).

Everyone at all levels, state and privately owned enterprises, academic institutions, and others – all these stakeholders though encouraged to make substantial financial and human resource contributions to the poverty reduction as an essential Rukun Negara patriotic national objectives – may not, however, raise to the tasks in hand.

Whether our civil servants would also be able to raise to a Madani Malaysia occasion is yet to be determined because this public sector is well-known for its lackadaisical attitude and inefficient performance as identified and elaborated in STORM 2022, Place Position Power; and reported in a World Bank study:

The elements constraining effort on improving public sector performance centre on administrative human-resource incapacity, a broadbase corruptive regime with burden of privileges mentality, a lost community soul living in a society laced with serial systemic odious practices, including money-laundering.

B) Infrastructural achievement has to be matched by considerable improvements in access to public infrastructure services, especially in the construction – and, later the maintenance thereon – of rural roads leading to poor areas. The construction of better access routes shall help in the irrigation and drainage facilities in poor areas, too, besides expanding on flood control and mitigation capabilities.

These aspects were clearly noticeable at the initial implementation of pioneer FELDA schemes which deteriorated once corporate capital intrusion and migrant labour influx into the plantations, (see STORM 2023, Big Money Big Farms; and STORM 2020, From FELDA to FGV.

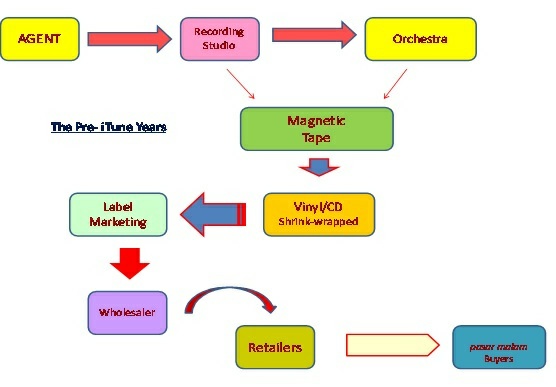

Importantly, the electronic roads – whether fibre optics and or 5G connectivity – onto the internet highways should not be ignored, (though, conscious of their retarding and degrading dimensions, (see STORM 2023, Digitalisation an Economy: short-circuiting the rakyat).

On the other hand, it has to be accepted that institutional innovations for targeted poverty alleviation have boosted by digital technologies for better efficiency, as in the advice by World Bank to Brazil on Bridging the Technological Divides.

Digital technologies have facilitated poverty targeting and also contributed to improving the connectivity of poor households to markets through e-commerce and facilitation of access to finance through new digital finance platforms as broadly demonstrated in China ability to eliminate poverty within a generation.

The Kerala “hop-step-jump” experience is another such success story whereby significant step with Vellanad village becoming the first fully computerised grama panchayat in India.

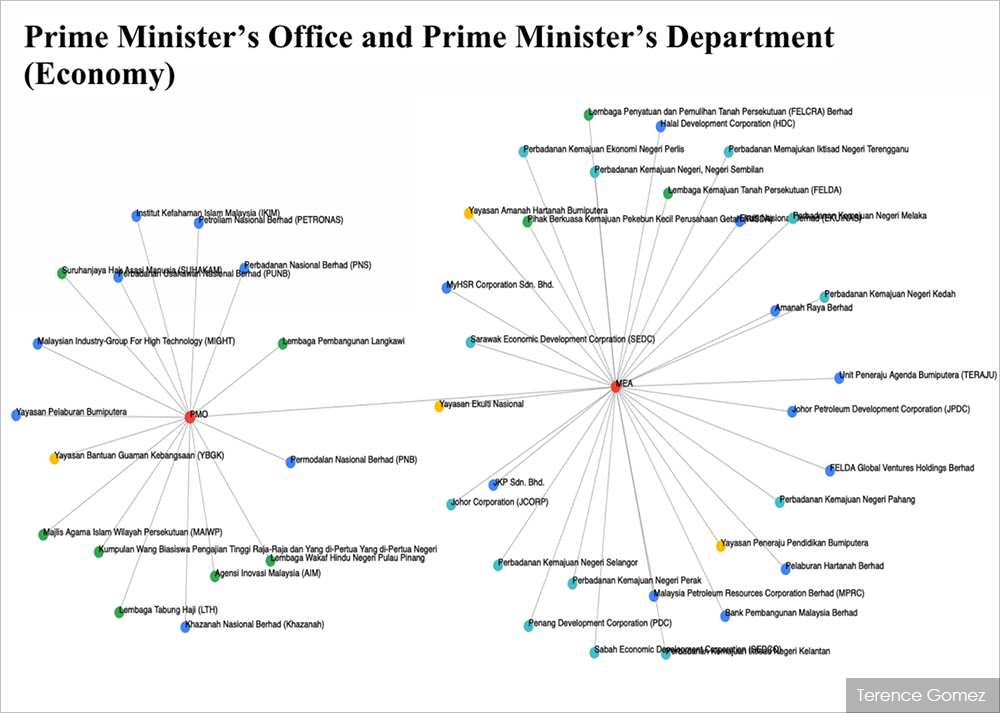

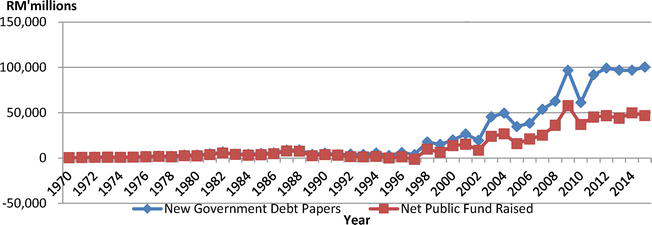

C) Fundings – dividends from Petronas, Khazanah, GLICs – whether would be able to boost a national economy and enlarge people’s incomes are not questionable. Nor would a new sovereign fund board be formed to debt service economic development towards a progressive growth path.

The evidence presented in all global studies where readily available financial resources points to significant positive spillover effects for all sectors of the economy and for poverty reduction. However, there may be significant service gaps remaining in specific rural areas, and within high-density residence on urban settings – particularly with respect to children health care and education services, (see. UNICEF 2022, Children Without).

Further, it has to be said that any political bias in local government incentives toward investments in hard infrastructure to boost growth and the reliance on special purpose vehicles arguably could perpetuate a misallocation of fiscal resources that could be costly in the long term (World Bank and DRC 2019).

Once an inclusive development path is followed and the implications for poverty reduction and socio-economic policies are adhering to the central core of social idealism of economic development with Malaysian characteristics – then, TAPAO is consumed, satisfactorily.

EPILOGUE

TAPAO to be successful has to adopt and adapt to a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach that would induce cooperation and collaboration across government and nongovernment stakeholders.

Without better governance, and mass participation by rakyat-rakyat, any goal of ending extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity will be out of reach.

The praxis of economic development should be evidenced by clear insight, determination and endeavour of rakyat-rakyat agitating with agility for a shared prosperity in a common wealth of a nation carrying forward the core values of all mankind.

References

Bikales, B. 2021. Reflection on Poverty Reduction in China. Swiss Agency for Development Cooperation, Bern.

Khazanah Research Institute, 2018, State of Households II.

Ravallion, Martin, 2009, Are There Lessons for Africa from China’s Success against Poverty, World Development 37(2).303-31.

Ravallion, Martin, 2011, A Comparative Perspective and Poverty Reduction in Brazil, China, and India. World Bank Research Observer 26 (1): 71-104.

STORM, 23/02/2023, Towards structuring economic development with sustainability

UNICEF Children – Without

World Bank and DRC (Development Research Centre of the State Council). 2019. Innovative China: New Drivers of Growth. Washington, DC: World Bank.

You must be logged in to post a comment.