PROLOGUE

1947, in the Swiss Resort named after: Mount Pelerin Society (MPS) held its first conference. The 39 members were economists, historians, philosophers, businessmen and where nine members later became Nobel Laureates — Hayek, George Stigler, Maurice Allais, Gary Becker, Milton Friedman, James Buchanan, Ronald Coase and Vernon Smith in Economics, and Mario Vargas Llosa in Literature.

1] INTRODUCTION

The MPS’s influence is to spread through opinion makers in journalism and think-tanks, supported by billionaire like Charles Koch. The think-tanks included the Institute of Economic Affairs (UK), Council on Foreign Relations, the Atlantic Economic Research Foundation, the Heritage Foundation and Ford Foundation, Hoover Institution, Foundation for Economic Education, American Enterprise Institute, Center for American Progress, Canadian Fraser Institute and Australian Institute of Public Affairs supported by plutonic billionaire families-like of George Soros, Michael Bloomberg, and Glenn Hutchins, (see Laurence H. Shoup, Monthly Review, May 2021 on key policy formulation and outcomes of major USA think-tanks).

However, much of the intellectual work was completed by University of Chicago’s Milton Friedman, Ronald Coase and George Stigler – working on free trade, the importance of property rights, political freedom and minimal state interference and low taxes.

These neo-liberal views were taken up by UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher (1925-2013) and US president Ronald Reagan (1911-2004), with nearly one third of latter economic advisers being MPS members. The neo-liberal philosophy and its application in economic policy eventually morphed into as the Washington Consensus, first articulated by World Bank economist John Williamson.

The concentration of neoliberal elites and circulation of neoliberal ideals amongst the political class.

2] NEO-IMPERIALISM AS NEW MONOPOLY IN PRODUCTION AND CIRCULATION

The internationalization of production and circulation, together with the intensified concentration of capital, monopolostic transnational corporations (TNCs) whose wealth is nearly as huge as that of many countries, for examples, in 2017 Walmart earned more than the whole of Belgium; Netflix had a greater revenue in 2017 than Malta’s GDP; Apple would be 47th in the world by GDP if it were a country.

The tendency towards the international concentration of capitalism is clearly reflected from Lenin’s contestaton (Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, New York: International Publishers, 1939) which points out that imperialism is the monopoly stage of capitalism where markets became competitive stages for global and regional hegemony.

To broaden capital intrusion there is “competition” between firms to seek low labour cost (economic term: labour arbitrage) and low-cost production processes (lean to just-in-time and flexible production), competition for resources and markets (strategic competitive advantages) and marketing on product differentiation (varied products with many features and multi-functionalities at various price structures in different marketspheres).

By 2008, the top one hundred global corporations which had shifted their production foreign affiliates or subsidiaries accounted for 60 percent of their total assets and employment and more than 60 percent of their total sales. The foreign direct investment (FDI) to developing economies was US$694 billion in 2018 making up 58% global FDI share. By engaging in contractual relationships with partner firms but without equity involvement, mostly in the Global South, TNCs were generating about US$2 trillion in sales in 2010 (UNCTAD, World Investment Report: Non-Equity Modes of International Production and Development (Geneva: United Nations, 2011), 131).

Between 1980 and 2013, benefiting from the expansion of markets and the decline in production factor costs, the profits of the world’s largest 28,000 companies increased from US$2 trillion to US$7.2 trillion, representing an increase from 7.6 percent to approximately 10 percent of gross world product, (see Richard Dobbs et al., Playing to Win: The New Global Competition for Corporate Profits (New York: McKinsey & Company, 2015).

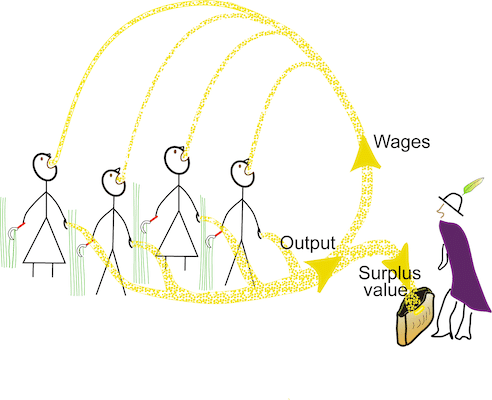

Under capitalism, the capitalists are dominant at each level of society, the working proletarians are dominated at each and every stage of labouring activities. When class exists at each economic, political, and ideological (or cultural) level, the understanding of class relationship is to identify where the controlling power ensues. As an instance, the stronghold in the Free Trade Zone (FTZ) or the Export Free Trade Zone (EFTZ) is that of monopoly-capitalism [place] that has aligned with the political elites and compradore capital of a developing country [positions], and by ownership and control of assembly workers [power] is able to extract the surplus value through their labouring tasks.

Those were the resultant outcomes of neoliberalism “free trade” ethos.

3] NEW MONOPOLY OF FINANCE CAPITAL

Secondly, the progress of capitalism to control and concentration generates a malformed development process towards economic financialization.

The international concentration of capital invertibly gives birth to international monopoly-finance capital that ensues the emergence of financialization capitalism (see John Bellamy Foster, The Financialization of Accumulation, Monthly Review vol:62, issue 05 October 2010). Financialization capitalism becomes prominent because the TNCs are unable to find sufficient investment outlets for their huge economic surpluses from production, increasingly turn to speculation within the global financial sphere, (see John Bellamy Foster and Fred Magdoff, The Great Financial Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2009). Even households had began to be financialized, too (see Costas Lapavitsas, The Era of Financialization, Part 3, TripleCrisis).

From the research of Cheng Enfu and Lu Baolin (Monthly Review May 2021), it is found that the proportion of overseas profits within total profits of U.S. corporations increased from 5 percent in 1950 to 35 percent in 2008. The proportion of overseas-retained profits increased from 2 percent in 1950 to 113 percent in 2000. The proportion of overseas profits within the total profits of Japanese corporations increased from 23.4 percent in 1997 to 52.5 percent in 2008, (Cui Xuedong, “Is the Contemporary Capitalist Crisis a Minsky-Type Crisis or a Marxist Crisis?” [in Chinese], Studies on Marxism 9 (2018).

By a slightly different accounting approach, it was acknowledged that the share of foreign profits of U.S. corporations as a percent of U.S. domestic corporate profits had increased from 4 percent in 1950 to 29 percent by 2019, (John Bellamy Foster, R. Jamil Jonna, and Brett Clark, “The Contagion of Capital,” Monthly Review 72, no. 8 (January 2021): 9).

Further, world wide, within twenty years since 1987, debt in the international credit market soared from just under $11 billion to $48 billion, with a rate of growth far exceeding that of the world economy as a whole, (Cheng Enfu and Hou Weimin, “The Root of the Western Financial Crisis Lies in the Intensification of the Basic Contradiction of Capitalism” [in Chinese], Hongqi Wengao 7 (2018).

4] MONOPOLY OF US$ DOLLAR AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Again, in Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin stated: “Typical of the old capitalism, when free competition held undivided sway, was the export of goods. Typical of the latest stage of capitalism, when monopolies rule, is the export of capital.” (Lenin, Selected Works, 212).

July 1944, on the initiative of the U.S. and British governments, representatives of forty-four countries gathered in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to discuss plans for a postwar monetary system. The documents Final Act of the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, and Articles of Agreement of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development – collectively known as the Bretton Woods Agreements – were adopted. The Bretton Woods main focus was to construct an international monetary order centered on the U.S. dollar. Other currencies were to be pegged to the US dollar, which was in turn pegged to gold.

The U.S. dollar thus plays the prominent role in world currency, while replacing the British sterling pound but designating the U.S. a special position compared to the rest of the world. Henceforth, U.S. dollar makes up 70 percent of global currency reserves, accounting for 68 percent of international trade settlements, 80 percent of foreign exchange transactions, and 90 percent of international banking transactions. Owing to this financial dominance, the U.S. dollar becomes the internationally recognized reserve currency and trade settlement currency. On one aspect, not only the United States is able to exchange it for real commodities, resources, and labour, and thus to cover its long-term trade deficit and fiscal deficit, but can also make cross-border investments, mergers and acquisitions of enterprises using U.S. dollars.

In a sense, the U.S. dollar hegemony provides one good example of the predatory nature of neoimperialism. The United States can also obtain international seigniorage by exporting U.S. dollars. She can reduce its foreign debt by depreciating the U.S. dollar or assets that are priced in U.S. dollars. The hegemony of the U.S. dollar has also caused the transfer of wealth from debtor countries to creditor countries. This would, in fact, mean that poor countries would subsidize the rich, which is completely and utterly unfair.

The other related financial instrument is the Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) which is a monopoly property. Intellectual property includes product design, brand names, and symbols and images used in marketing. These are protected by rules and laws covering patents, copyrights, and trademarks. Figures from the UN Conference on Trade and Development show that royalties and licensing fees paid to multinational corporations increased from $31 billion in 1990 to $333 billion in 2017, (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, World Investment Report 2018).

According to figures from Science and Engineering Indicators 2018 Digest, released by the National Science Council of America in January 2018, the total global cross-border licensing income from intellectual property in 2016 was $272 billion. The United States was the largest exporter of intellectual property, with such source income at 45 percent of the global total.

With the TRIPs/WTO (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) as an international legal agreement between all the member nations of the World Trade Organization), the intellectual property regime has only strengthened, henceforth, (Cédric Durand, William Milberg, Intellectual Monopoly in Global Varlue Chains, 2018).

5] NEW MONOPOLY OF INTERNATIONAL OLIGARCHIC ALLIANCE

The fourth point is that with permeability of neoliberal thinkings prod a string of international monopoly alliance of oligarchic capitalism, featuring thereby a hegemonic ruler and several other great powers. This introduction is to provide the economic foundation for the money politics, vulgar culture, and military threats that exploit and oppress on the basis of the monopoly, as articulated by Cheng Enfu and Lu Baolin in Monthly Review May 2021, ibid).

Examples of international monopoly economic alliance as dominated by the United States are the 1975-formed G6 group with the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, and Italy, and became G7 when Canada joined the following year. G7 and its monopoly organizations are the coordination platforms, while the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization are the functional bodies of the new Bretton Woods global order of economic governance international capitalist monopoly alliance manipulated by the United States to serve its strategic economic and political interests, (Youzhi and Zha Junhong, “The Evolution and Influence of the G7 Group after the Cold War” [in Chinese], Chinese Journal of European Studies 6, 2002).

Other hegemony entities shall comprise the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and regional collections like ANZUS — the Australia, New Zealand and U.S. Security Treaty, Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship, The US-Israel Strategic Partnership, The U.S.–Afghanistan Strategic Partnership Agreement, the QUAD in an India-Pacific coalition, PRISM and the Five-Eye program as part of multilateral UKUSA Agreement – a treaty for joint cooperation in signals intelligence.

6] ECONOMIC ESSENCE AND TREND

The final characteristic of neoliberalism is the globalized contradictions of capitalism and its various crises of the system creating contemporary capitalism as late imperialism (Patnaik 2016), where U.S. political scientist like Joseph Nye had articulated that soft power may be applied to accomplish one’s desires through attraction rather than force or purchase.

It is often presented that the soft power of a country is constituted mainly of three resources, namely, culture (which functions where it is attractive to the local population), political values (which function when they can actually be practiced both at home and abroad), and foreign policy (which functions when it is regarded as conforming to legality and as enhancing moral prestige), see Wang Yan, “Review of Research on the Index System of Cultural Soft Power” [in Chinese], Research on Marxist Culture 1 (2019).

The United States subjugates the cultural markets and information spaces of other countries, especially developing countries, by exporting to them U.S. values and Hollywood lifestyles, with the goal of making its culture the “mainstream culture” of the world, (see Hao Shucui, Research on Marxist Culture 1, 2018) from Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation, Mont Pelerin Society, and Center for International Private Enterprise to promotion of “color revolutions” – through Albert Einstein Institute (AEI), National Endowment for Democracy (NED), International Republican Institute (IRI), National Democratic Institute (NDI) – by controlling the field of international public opinion via the promotion of neoliberal values by funding seminars and academic organizations, and through broadcasts by Voice of America and CNN or publications in Bloomberg, USAToday, New York Times, and increasingly since 2009, the US Agency for Inter-national Development (USAID)’s Interagency Counterinsurgency Initiative became official doctrine in the US. Now, USAID is the principal entity that promotes the economic and strategic interests of the US across the globe as part of its counterinsurgency operations.

7] IMPACT UPON MALAYSIA

The spectre of neoliberalism and neocolonial economic development surfaced after independence.

The British assisted in scripting an economic policy known as the Draft Development Plan that would became the Malaya Plans (1955-60); also implemented was the Second Malaya Plan 1961-65.

There seems to be a greater deference to foreign economic advisers who not only represent the neoliberal interests of international economic agencies but also enhancing the foreign business interests that successed in penetrating wholesomely the national economy.

a) Then, the subsequent three Malaysia Plans that followed were said to be crafty masterminded by foreigners from the United States of America. In fact, the earliest Malaysia Plan was drafted with the advice of Warren Hansbuger from USA; the second plan was completed by Prof. V.M. Bernett, Dr. D. Snodgrass and Prof. H.J. Bruton, all from the USA; though Snodgrass had pointedly admitted that these programmes were to gain “support from the rural Malays, if not indeed for the leadership of UMNO itself” rather than as a wholesome beneficiary to the rakyat-rakyat. The third plan had the advice of Prof. B. Higgins, also from the USA. The Development Advisory Service of Harvard (DASH) was heavily involved with the Prime Minister Economic Planning Unit (EPU) in drafting and promotion of this suite of development programmes.

Later in 2010, the government think-tank – Performance Management on Delivery Units (Pemandu) – even had allocated RM66 on “external consultants”, including American consultancy firm McKinsey and Co, which took the lion’s share of an estimated RM36 million; other foreign consultants included the Hay Group (which was paid RM11 million), Ethos & Co (RM1.5 million) and Alpha Platform (M) Sdn Bhd (RM1.5 million); an undisclosed “external consultant” named “Tarmidzi” had also received RM3 million for work done in setting up Pemandu as part of a neoliberalism economic development collaboration.

During 1997 currency crisis, and the eventual financial meltdown in 1998, the Malaysian government initial response was to rely on the International Monetary Fund consultancy response requiring expenditure reduction policies, that is, tighter fiscal and monetary control, which most unfortunately exacerbated the recessionary situation within the country concurrent with sharp portfolio capital outflow (see Athukorala 2000, “Capital Accounts Regime, Crisis, and Adjustments in Malaysia”, Asian Development Review 18, No:1 ,pp:17-48 and Bird & Rajan 2000, besides Kaplan and Rodrik 2001, “Did the Malaysian Capital Controls Work?”, NBER Working Paper No:8142).

b) TNCs deployment abroad is a manifestation towards capitalism late imperialism notation of labour arbitrage. On one side, the political economies of newly independent countries encourage foreign investment from Global North monopoly-capital. On the other perspective, through the application of global labour arbitrage where, as a result of the removal of or through the disintegration of barriers to international trade, jobs and industries have since moved to nations where labour and the cost of doing business is with low-pay and operational costs are inexpensive, respectively. This approach, together with labour value commodity chains, contributes to the enlarged capital accumulation by the transnational corporations, deepening the extracting surplus value from the labouring class.

However the uneven labour employment was to be seen in the Second Malaysia Plan, 1971-1975, where it had proposed that 22% of the 495,000 new jobs to be created in peninsular Malaysia would be in the manufacturing sector. This means a three folds increase in employment in the manufacturing sector from the 1960 figure of 121,000 to 378,000 by 1975. Past performance had shown that the low employment absorption capacity in the manufacturing sector, especially in the pioneer companies; in fact, the manufacturing sector provided only 5,500 new jobs per year during 1966/67,(Lo Sum-Yee, The Development Performance of West Malaysia, 1955-1967, with special reference to the industrial sector, Heinemann, Kuala Lumpur, 1972, Chapter 7, pp.66-73 and E.L. Wheelwright, Industrialisation in Malaysia, University of Melbourne Press, 1965, Chapter 4, pp.62-70).

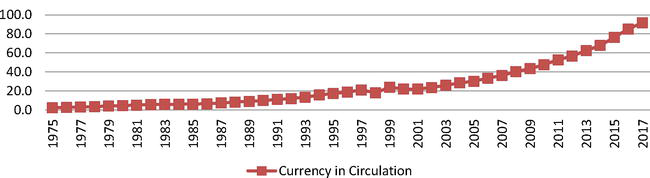

c) Thirdly, without promulgated regulations, financial monopoly capital is very likely to work against the vision and goals set by country for her industrialisation initiatives. The insurgent of capital financialization in the late 1990s had already created an increased circulation of paper instruments and their associated debts :

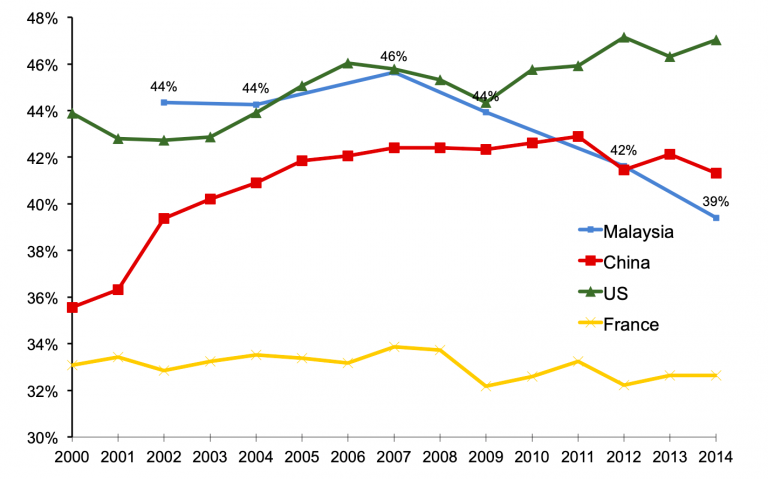

d) Forty-five years after the New Economic Policy (NEP) implementation, by 2002, Malaysia’s inequality remains extremely high: its top 1 per cent income share was 19 per cent and the corresponding number for the top 10 per cent was 44 per cent which is higher than those of the US and substantially even higher than those of China :

e) The unpleasantness on why many Malays had not attained parity despite +60 years of neo-liberal-enforced economic development is the emergence of a new class of compradore capitalist. With post-industrialidation and the introduction of financialization capitalism, the role of clientelship capitalism had inserted into the monopoly-capital supply chain in an age of imperialism. Corporate capital in the SMEs collaborates with Global North to tighten the commodity supply chain with monopoly-capital M&E vendors like AIDA, SKF, Cohu, VAT, Oerlikon Balzers, Favelle Favco, Bromma, Vitrox, etc.; recently, Digi, Nestles and British American Tobacco are, by market capitalisation, leading the list of foreign companies that dominate our local businesses.

f) the emergence and ascendancy of ethnocapital clientel capitalism had witnessed the consolidation of ethnocratic clientel capitalism postcolonial affinity in the country as well as the constructed concentration of economic power in the banking, pharmaceutical and infrastructural platform sectors – all coexisting with neoliberalism economic developmental policies that aligned with late imperialism monopoly-capital and financial monopoly-capitalism.

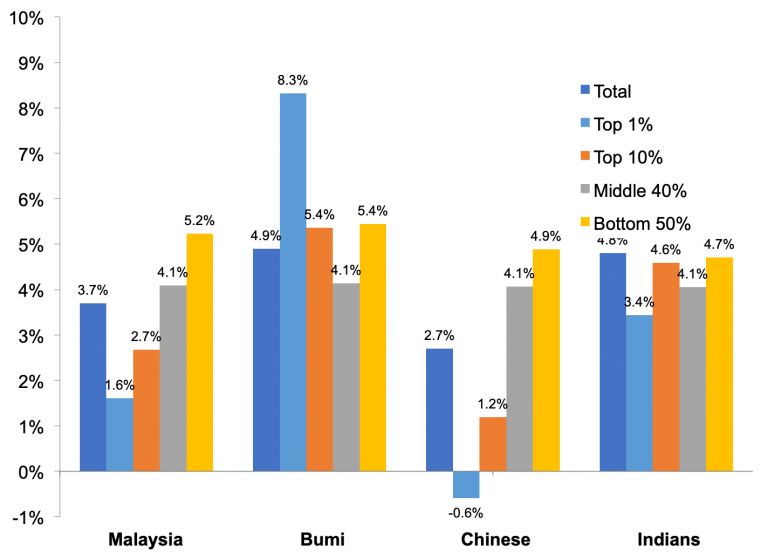

g) benefits from “economic development” and growth did not trickle down to everyone, and that only the well-connected capital cronies who, through rentier capitalism and clientele corruption, had enjoyed the immense wealth of development. Everyone had seen a marked rise in absolute inequality through the years:

h) That what is widely referred to as neoliberal globalization in the twenty-first century is in fact a historical product of the shift to global monopoly-finance capital.

The politico-economic stage the country is presently stationed confirms Amin’s imperialism of generalized-monopoly capitalism and Emmanuel’s unequal exchange under Neo-Imperialism.

Jason Hickel, Dylan Sullivan and Huzaifa Zoomkawala contended in the New Political Economy – published online: 30 Mar 2021 – that wealth drain from the Global South remains a significant feature of the world economy in the post-colonial era; rich countries continue to rely on imperial forms of appropriation to sustain their high levels of income and consumption. The Global North appropriated from the Global South commodities worth US$2.2 trillion in Northern prices that are enough to end extreme poverty 15 times over; and we are unfortunately one of the politico-economic victims in this neoliberalism niche.

8] CONCLUSI0N

The character of neoimperialism is that it is a monopolistic financial capitalism established on the business model of giant and expansive transborder multinationals. The production monopoly and financial monopoly of the transnational corporations have higher stage of production and capital concentration, whereby “nearly every industry is concentrated into fewer and fewer hands.” (see John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, and R. Jamil Jonna, “Monopoly and Competition in Twenty-First Century Capitalism,” Monthly Review 62, no. 11, 2011 :1).

International monopolistic financial capital not only controls the world’s major industries, but also monopolizes almost all sources of raw materials, scientific and technological talent, and skilled physical labour in all fields, controlling the transportation hubs and infrastructural platforms by various modes and means of production. It owns, controls and dominates capital, global financial functions and associated derivatives and information technologies through vast culutural and military shareholding systems, (Li Shenming, “Finance, Technology, Culture, and Military Hegemony Are New Features of Today’s Capital Empire” [in Chinese], Hongqi Wengao 20, 2012).

October 1984, Deng Xiaoping stated: “There are two major problems in the world that are very prominent. One is the issue of peace and the other is the North-South issue. Deng emphasized that “peace and development” were the two major questions to be resolved, (Li Shenming, “An Analysis of the Age and Its Theme” [in Chinese], Hongqi Wengao 22, 2015), not perpetuating endless wars and destructive extractions upon Mother Earth.

EPILOGUE

Progressive nations working together to build a shared socialist community for the better future for humankind.

You must be logged in to post a comment.