Capitalism has become increasingly nomadic, leaving a trail of social-economic disorderliness and disarrangement in its wake.

The turbulents create Capitalism: crisis to crisis.

CONTENTS

1] INTRODUCTION

2] PETRONAS, PEASANTRY AND THE PROLETARIATS

3] THE DEVELOPMENT OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT

4] CORPORATE CAPITAL, RENTIER CAPITALISM AND THE CLIENTEL CAPITAL CLASS

5] LABOUR, CLASS AND ALIENATION

6] CIRCUITRY OF CAPITAL

7] ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS

8] MADANI MALAYSIA

9] EARLY MALAYSIAN TRILOGY

[click each bold LINK: goto a MANUSCRIPT]

( click see soft link : goto external sources )

1] INTRODUCTION

Capitalism important trends in recent history:

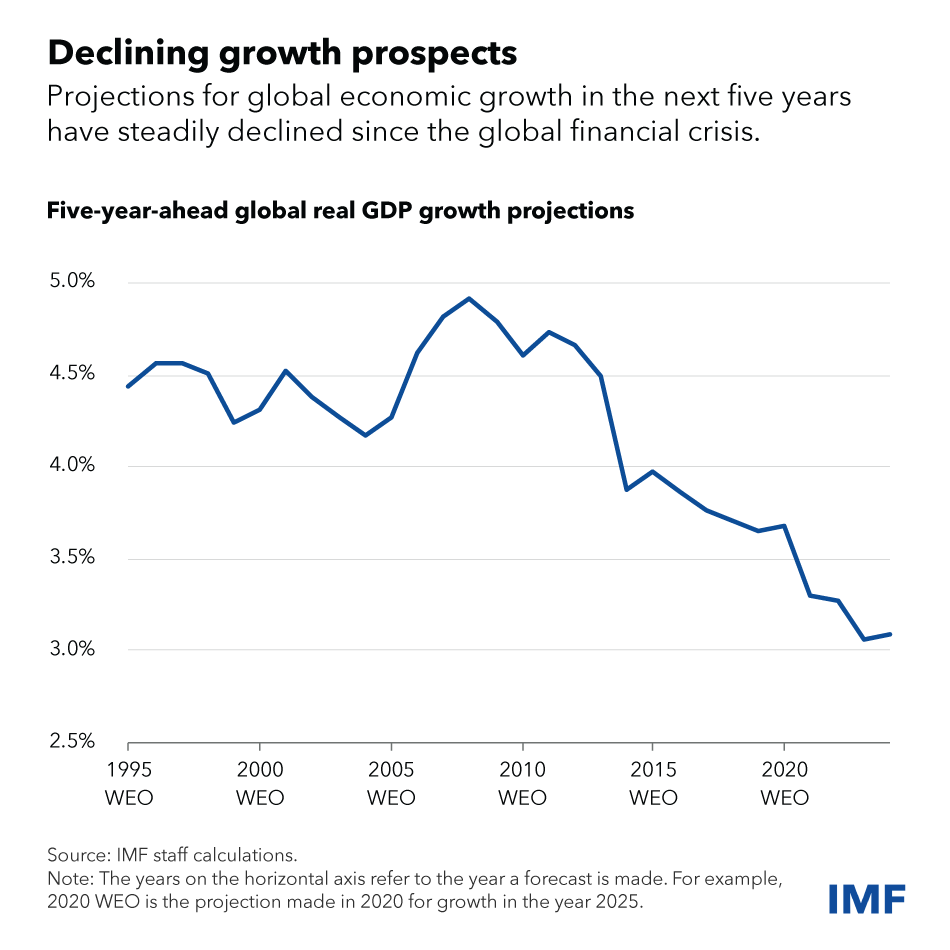

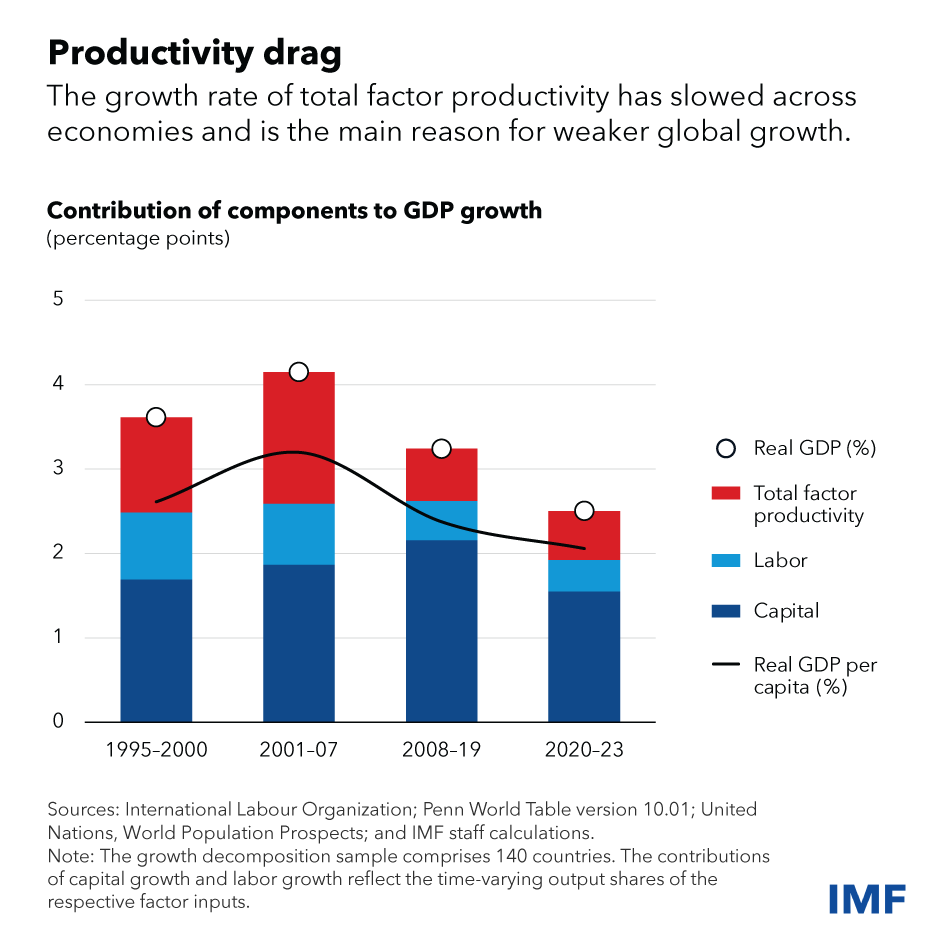

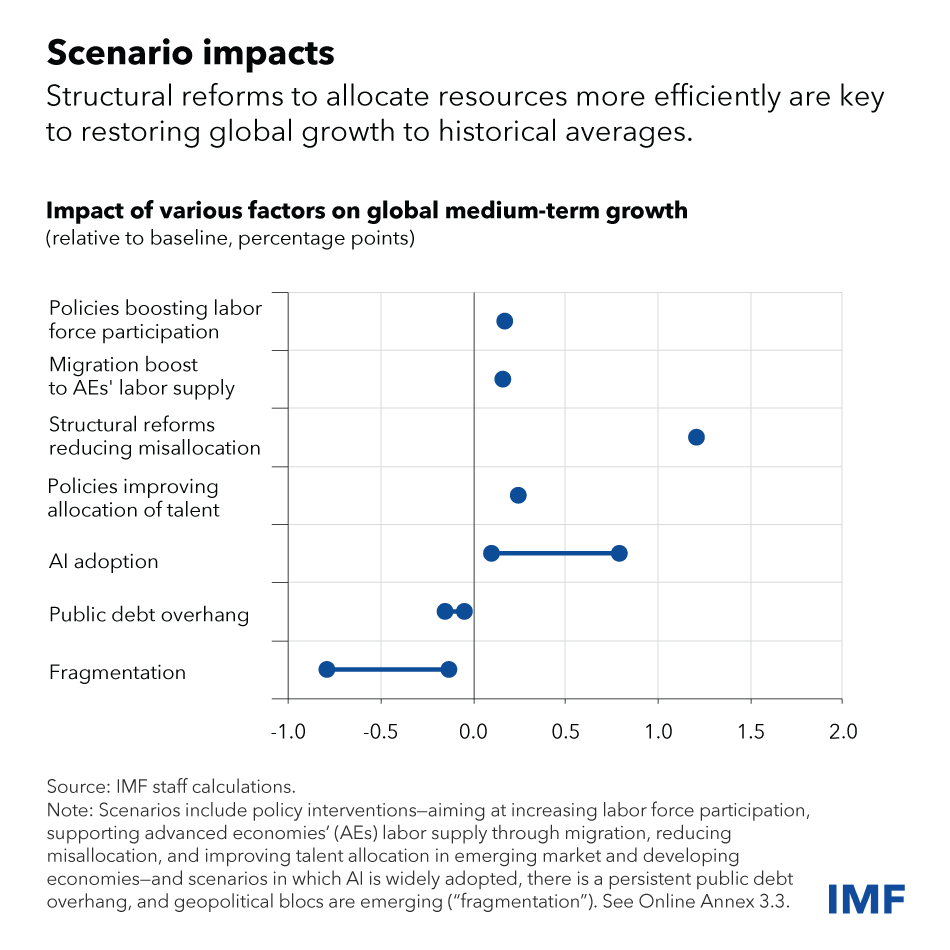

(1) slowing down of the overall rate of growth;

(2) internationalisation of monopolistic transnational corporations (TNCs); and

(3) emergence of the “capital accumulation process” or financialization capitalism

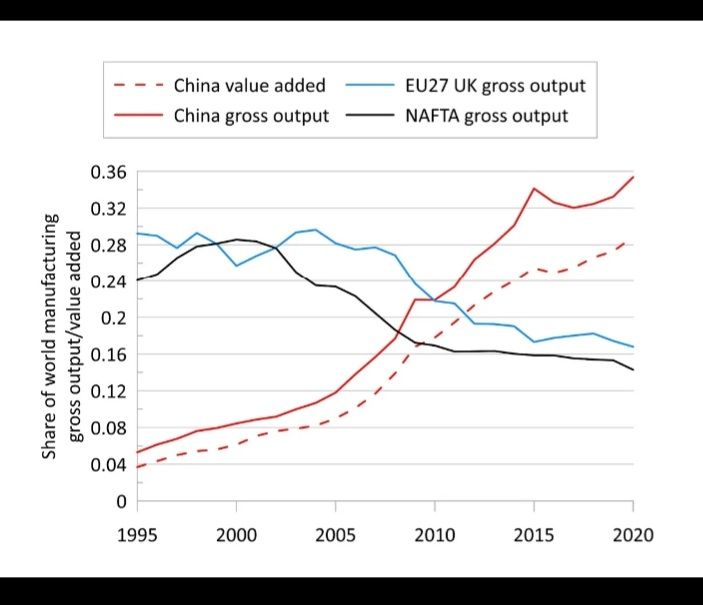

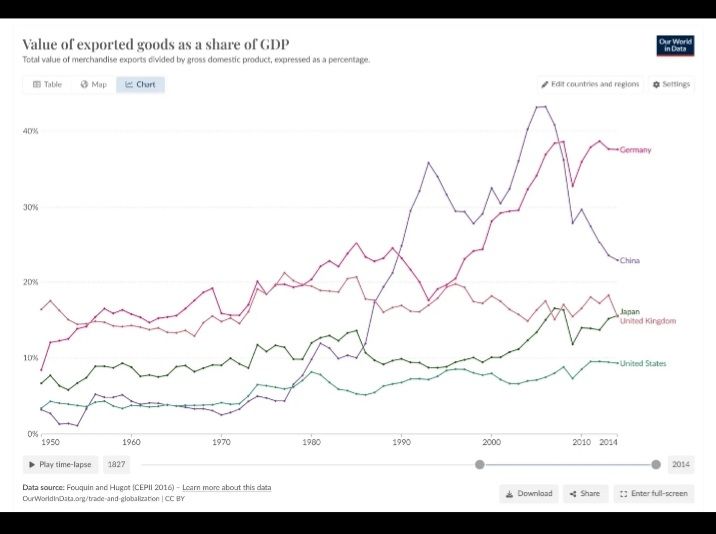

a) Since the 1974-1975 recession, there is a growth rate slowdown in advanced capitalist economies with impactful economic effects on the poorest countries. Scouting for wider markets to sustain capitalism, a proliferation of corporations – with neoliberalism policies – begins setting up assembly lines across borders in different geographical locations, especially inside developing countries – the Global South – where in 2010, more than half of all foreign direct investment (FDI) went to third world and transition economies. With this strategic positioning in place, and world production dominated by a relatively few transnational corporations (TNC) exercising considerable monopoly power over states and labour, the migration towards the international concentration of capital clearly reflected on the work of Lenin (Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, New York: International Publishers, 1939) and, on the other hand, confirms Amin’s imperialism of generalized-monopoly capitalism and Emmanuel’s unequal exchange under Neo-Imperialism that initiated underdevelopment under monopoly-capitalism through sheer exploitation.

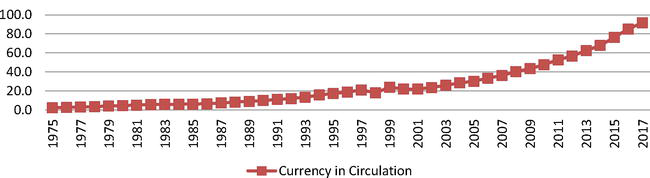

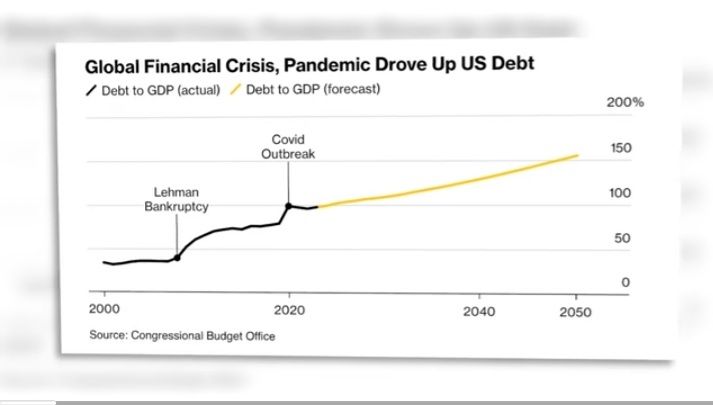

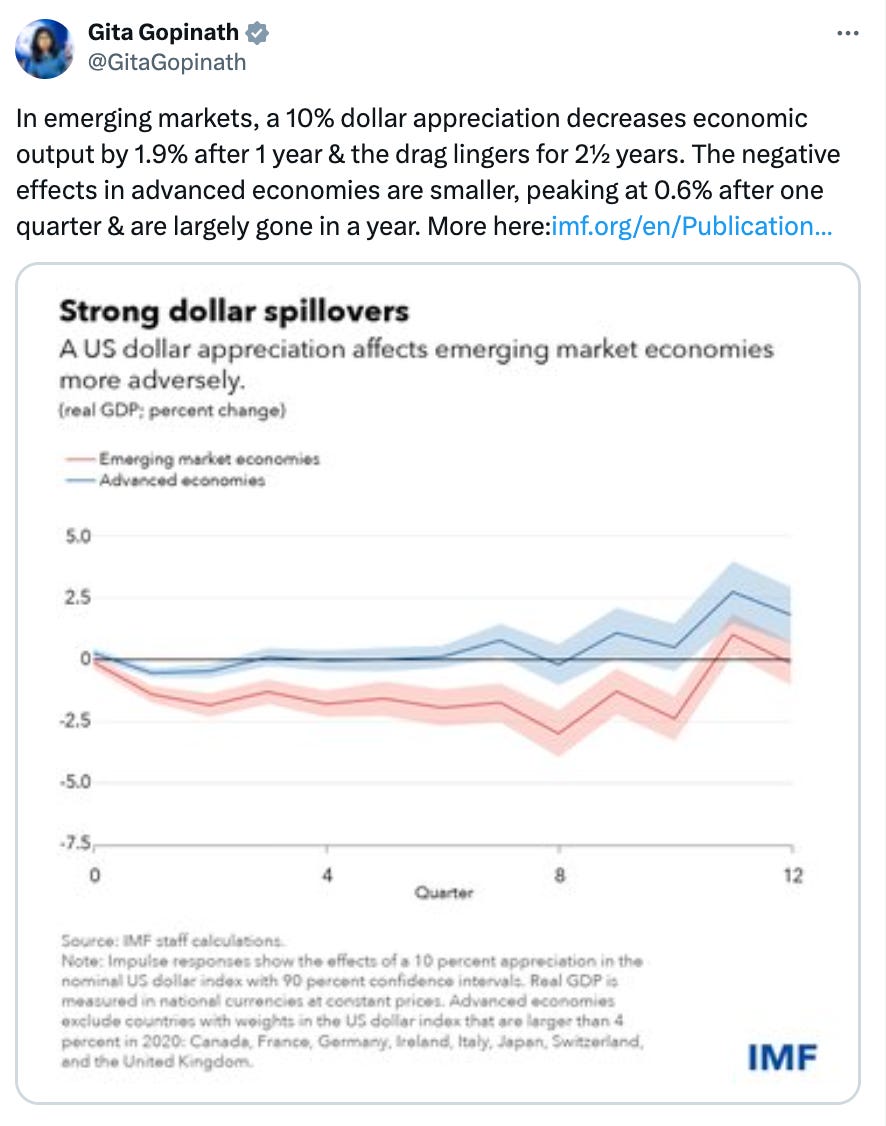

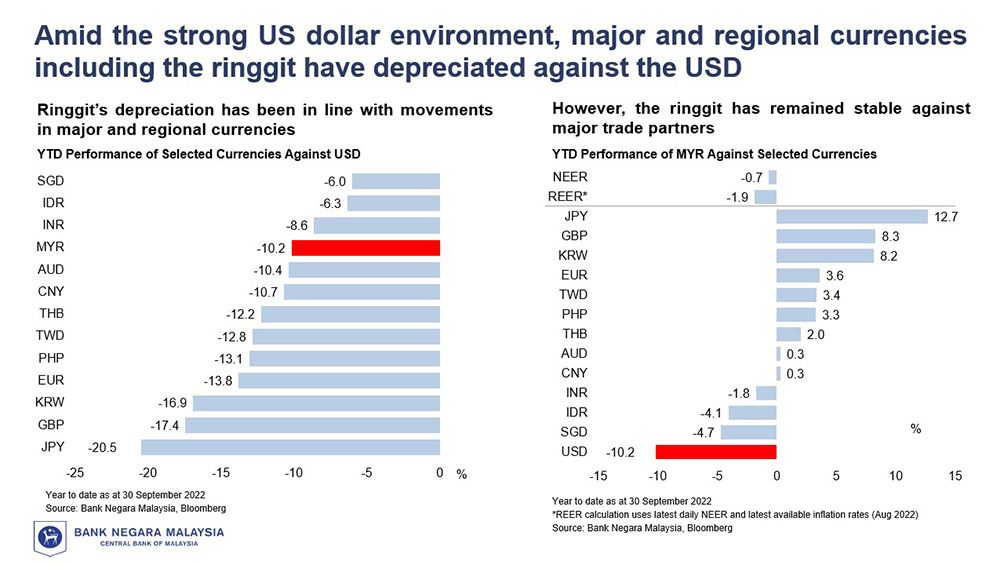

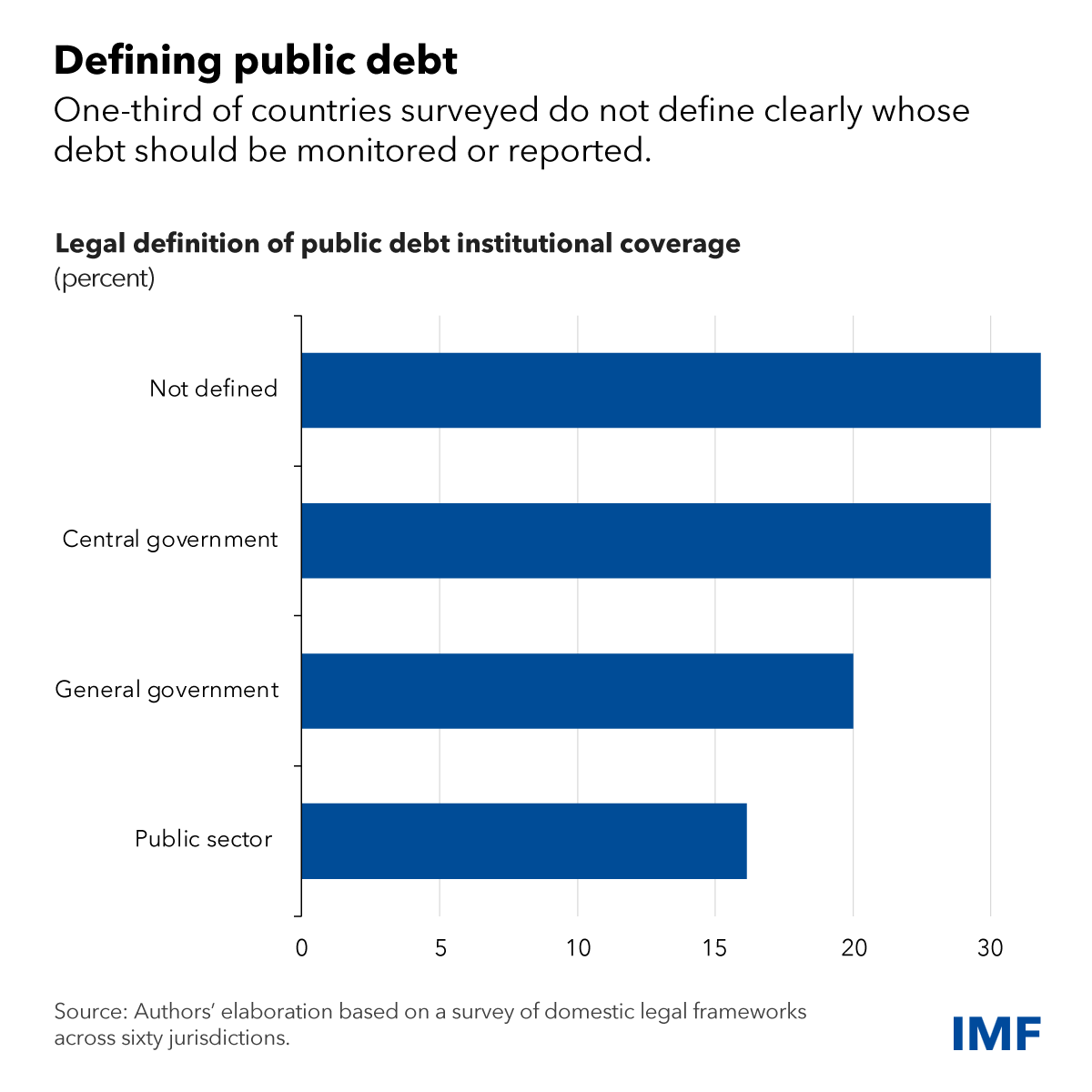

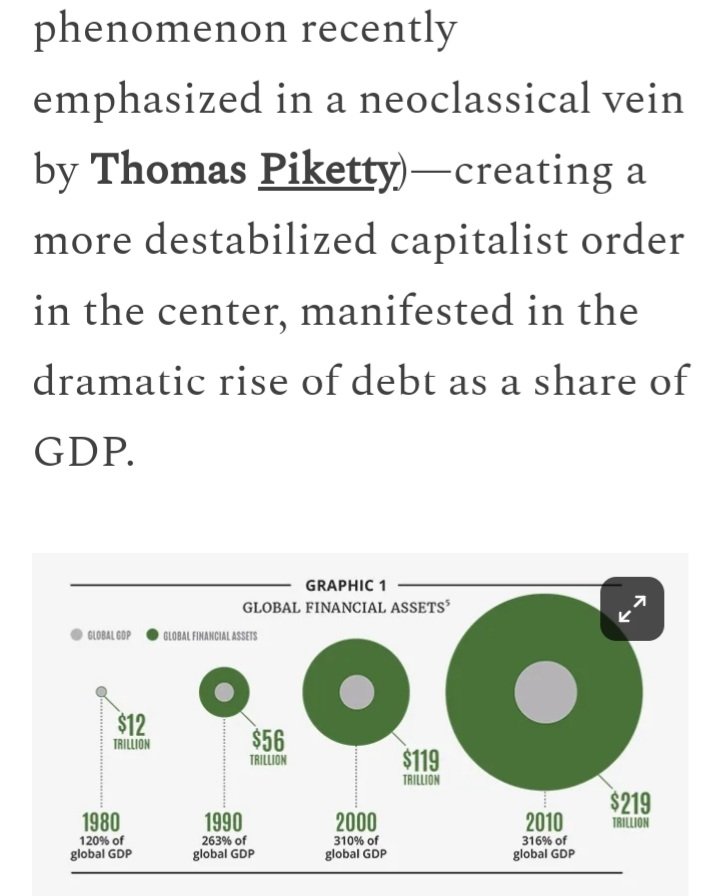

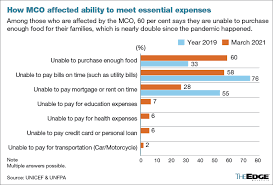

The international concentration of capital invertibly gives birth to international monopoly-finance capital that ensues the emergence of financialization capitalism (see John Bellamy Foster, The Financialization of Accumulation, Monthly Review vol:62, issue 05 October 2010). Financialization capitalism becomes prominent because the TNCs are unable to find sufficient investment outlets for their huge economic surpluses from production, increasingly turn to speculation within the global financial sphere, (see John Bellamy Foster and Fred Magdoff, The Great Financial Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2009). Even households had become financialized, (see Costas Lapavitsas, Financialised Capitalism: Crisis and Financial Expropriation, Historical Materialism 17 (2009), School of Oriental and African Studies, London and Costas Lapavitsas, The Era of Financialization, Part 3, TripleCrisis). In the country, financialization capitalism is engaging – and entangling – the political economy of Malaysia even during a Covid19 pandemic situation when such capitalism is as contiguous as the virus itself, and became the dominance of financial monopoly-capitalism in the nation, and consequently indebted the country. The urban poors are distressing in debts as reported by UNICEF 2020. The collusion of monopoly-capitalism with clientel capitalism is clearly evident during the acquisition, distribution and Covid19 vaccination processes.

b) Malaysia, within a world economy infused with capitalism, has a neo-colonialism economy past where a particular racial class of succeeding ethnocapital kleptocracy regimes exist in looting national coffers essentially through illicit capital and illegal tradings after her independence from British colonial master, inadvertently perpetuating the consolidation of ethnocapital clientel capitalism.

c) That what is widely referred to as neoliberal globalization in the twenty-first century is in fact a historical shift to global monopoly-finance capital (see Samir Amin imperialism of generalized-monopoly capitalism) taking on a new phase in the globalization of production and finance.

During the 1970s, Malaysia went through an industrialisation initiative though did not employ as many workers as projected, but FDI still created an underdevelopment in monopoly-capitalism environment that inevitably invited these TNCs exploiting precarious labour. Presently, the few TNCs dominating particular industries or in the sectors of electrical and electronic production are confronted with a dialectic of rivalry and collusion: the mobile phone industry and a infrastructural platform, like Google, are prime examples of the control of telecommunication services.

d) There is a “competition” between firms in search for low labour cost (economics term: labour arbitrage) and low-cost production processes (operations management from lean to just-in-time and flexible production), competition for resources and markets (strategic management term: competitive advantages) and marketing principles on product differentiation (varied products with many features and multi-functionalities at various price structures in different marketspheres).

By 2008, those top one hundred global corporations which had shifted their production to foreign affiliates or subsidiaries accounted worldwide for 60 percent of their total assets and employment, and more than 60 percent of their total sales.

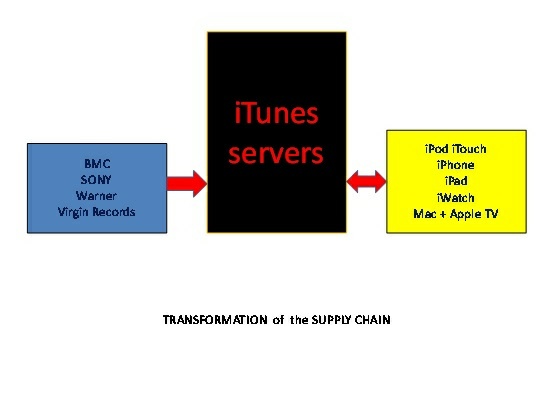

e) During an era of global monopoly-finance capital, financial capital is part of the transnational migration of capital with Information Technology augmenting the monopolisation trends primarily, ( see John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney, The Internet’s Unholy Marriage to Capitalism, Monthly Review 62, no. 10 (March 2011): 1-30). Increasingly, capital accumulation – real capital formation in the realm of goods and services – has become widely subordinate to finance, including the public healthcare and pharmaceutical providers, housings development through Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) and others.

Whereas labour ( owing to a combination of cultural, political, economic, legal and geographical reasons ) is rooted in particular nations – ensuring a constant and growing supply to the global reserve army of workers – capital is globally mobile, thus consolidating the Global Labour Arbitrage advantages with Global Value Chains.

This Capital Internationalisation fragments, and weakens, labour organizations, and during the Covid19 pandemic especially in union bursting regionally, including Malaysia specifically.

2] PETRONAS, PEASANTRY & THE PROLETARIATS

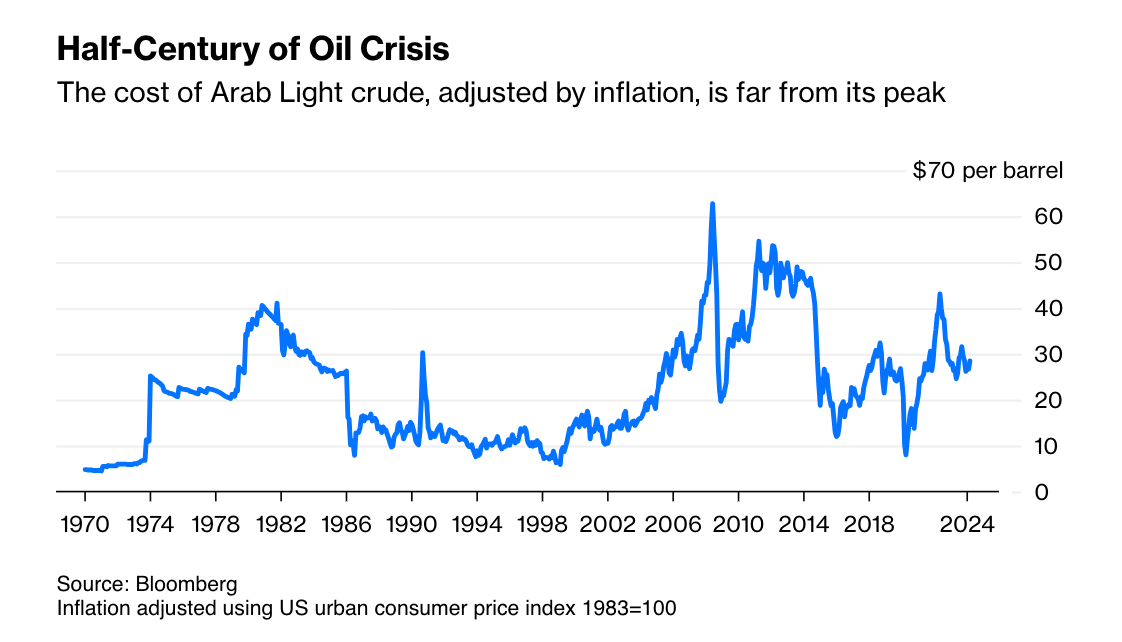

a) In the 1970s so it comes about with the discovery of oil and gas, and in a beachhead, the Big Oil controlled the exploitation along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, and on the South China Sea off Sabah and Sarawak. The ensuing Neo-Imperialism penetration tilted an economic development paradigm shift: an intensified economic nationalism – culminating with the Guthrie Dawn Raid – a focused ethnocratic inclination that firmly reconstructed the strengthening stronghold of an ethnocapital hegemony of the ruling class. These factors contribute to consolidation of rentier capitalism as was enmeshed in the New Economic Policy (see Jomo 2004, SME 2019). The associated negative ramifications that surfaced perpetuates a burden of privileges in the economy (see Sadhive) that need to be reviewed and restructured, if not, rejected.

b) Concurrently with the energetic endeavour in O&G exploitation is the promotion of the rural community FELDA scheme that was envisaged to forestall possible Urban-Agrarian collaboration and cooperation for revolutionary changes towards a new peasantry-proletariat political economy in Malaysia. Supposedly to be corridor sanitarian to corral rural Malay communities with modern built-in infrastructure – with clinics, schools, roads and bridges – ensuring subsistence dependence with loyalty to the ruling class and the transnational corporation presence in the FTZs and EFTZs (Exports Free Trade Zones) to mop-up precarious labour.

What is acclaimed as “accumulation by dispossession,”(see David Harvey, 2019) with the mass global removal of peasants from the land by Big Farm agribusiness and peasant migration to overcrowded cities yet to encounter dialectical urbanism in capitalist enclaves – from FELDA to FGV – has greatly increased the “reserve” industrial reserve army of labor worldwide, but landless impoverishment culminating in the students’ Baling Hunger Strike.

3] THE DEVELOPMENT OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT

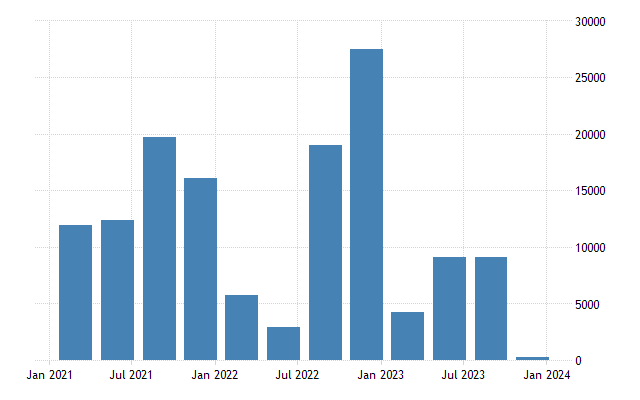

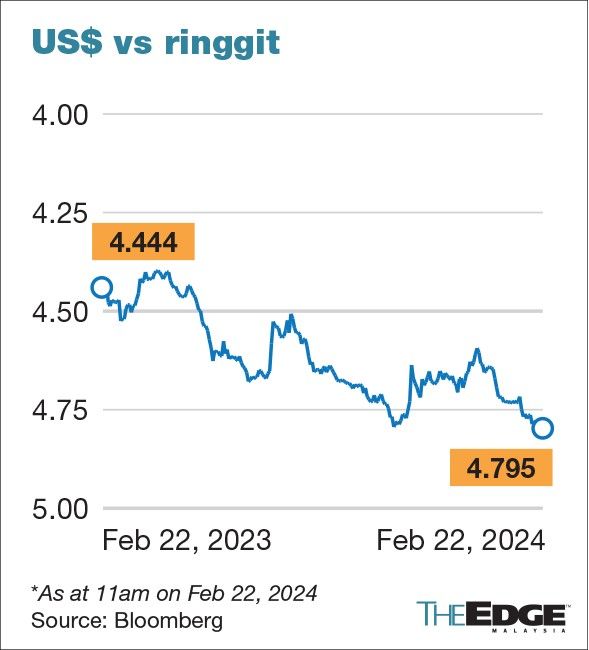

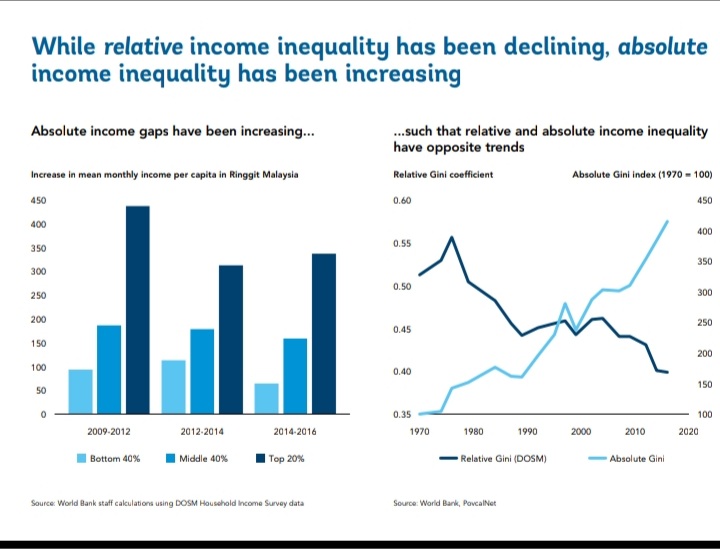

NEP consequential follow through, as stated, is the emergence of clientel capitalism solidified into an ethnocapital hegemony. The subsequent Asian Financial Crisis (AFC1997) and the Global Financial Crisis (GFC2007) tanked the country with a stagnant economy (see Sadhive 2020) – whereby the country is forever mired in debts with profound poverty among rakyat2 and inequality in wealth distribution. To compound the politico-economic landscape is that often we have big budgets, bad debts accompanied by a bad government after the Sheraton Move in 2020, and its aftermath (James Chin 2020; Bridget Welsh 2020).

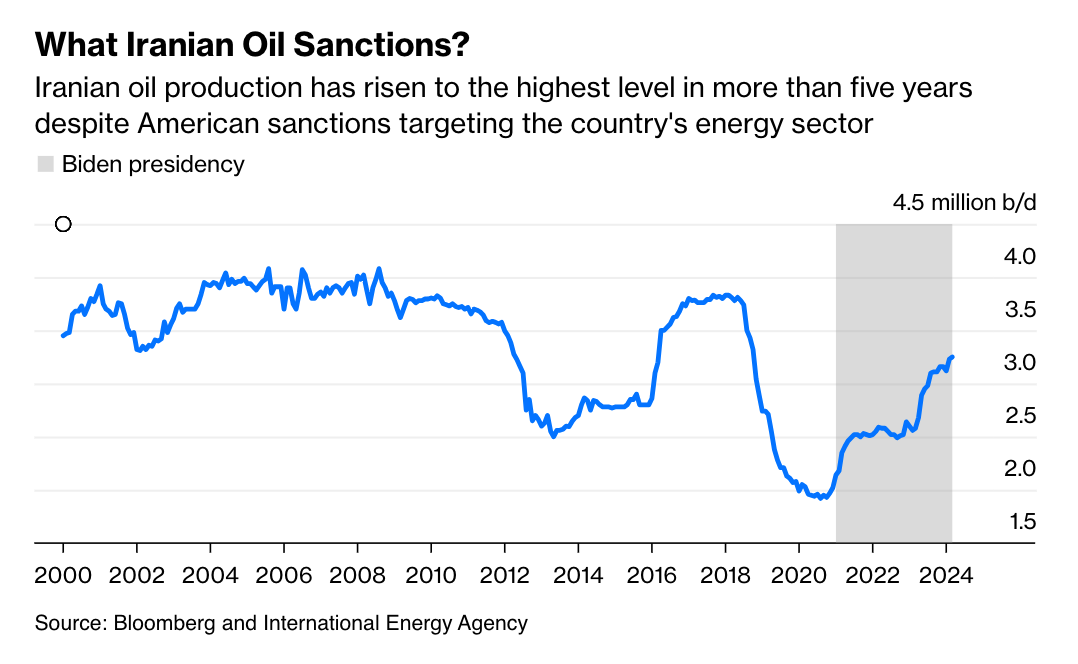

The country is a case in development of underdevelopment even to her member states so much so that besides stripping the nation’s endowed potentialities under the auspice of GLC’s ownership and control, she also sold out to Big Oil (see also Rob Urie, Oil Imperialism and Monetary Policy, 25/03/2015, counterpunch); the accompanying intra-state political intrigues and deft maneuverings (see James Chin 2020, 2018, 2016; MA63) have yet to subside.

4] CORPORATE CAPITAL , RENTIER CAPITALISM AND THE CLIENTEL CAPITAL CLASS

The political economy of the country thus rests upon an agenda of neoliberalism favouring corporate capital colluding with clientel capitalism locally to connect with Global North monopoly-capital, besides getting entangled under a Ecological-Epidemiological-Economic crisis during a covid19 pandemic.

Linking the conduit of monopoly-capital connections, whether as in Apple Corp. case or HERE, and locally like the Top Grove, is that where financialization capitalism is playing a big role in gourging the financial domain than promoting productivity, research and development breakthroughs nor wider market coverage as under industrialisation.

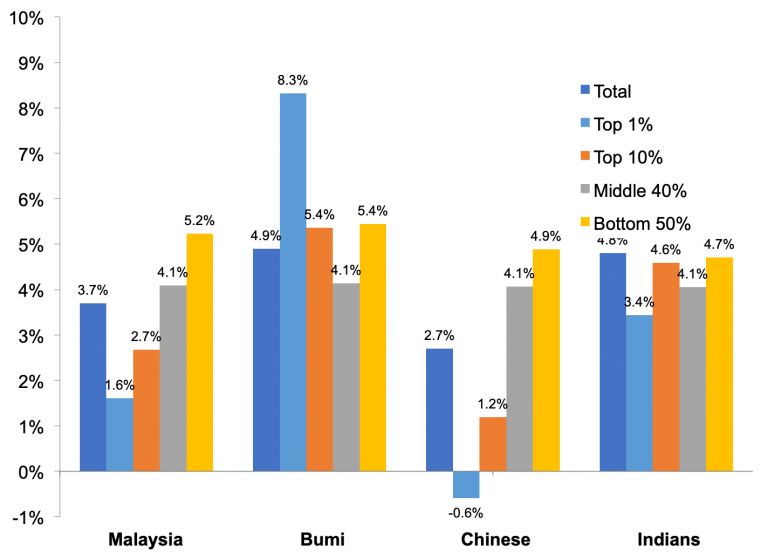

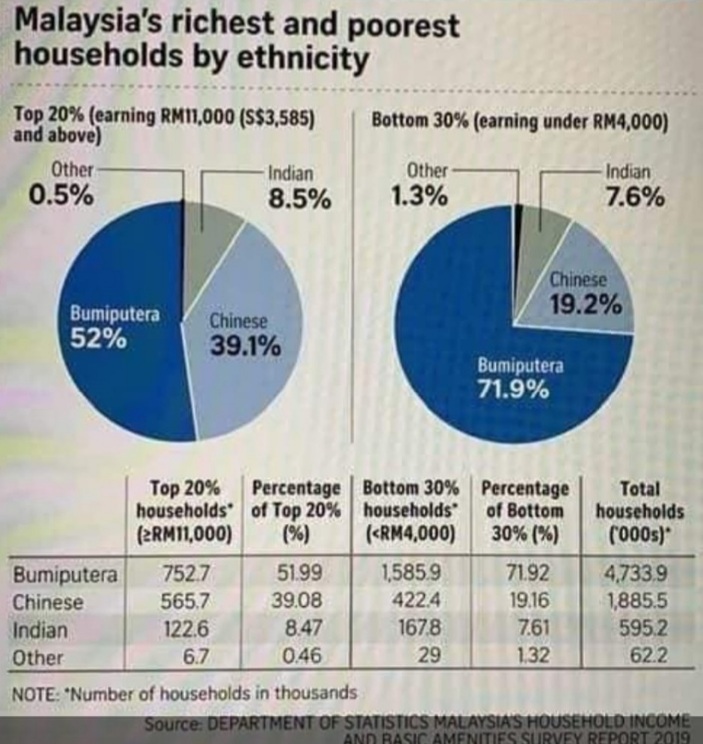

The implementation of the enthnocratically-administrated National Economic Policy in 1970, (see, selectively: Navaratnam 2020, Zainuddin 2019, Jomo 2005,) where succeeding oligarchy regimes had continued maintaining a clientel ethnocapitalism domination over the working class rakyat2 with 1% of the bumiputera population (see Khalid lse.blog) or about 40,000 ethnocapital political families running and looting – and ruining – the national economy in alliance with Global North monopoly-capital – all in furtherance of neo-imperialism penetration that by now the ownership of a failed state, (see Aliran 2021).

An ethnocratic governance is where representatives of an ethnic group is holding a disproportionately large number of public posts to advance their ethnic group to the disfranchisement of others, (see Winter, J.A., Oligarchy, Cambridge University Press, 2011 and Wade, G., The Origins and Evolution of Ethnocracy in Malaysia, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, Working Paper Series 112, April 2009), including enforcng political Islam.

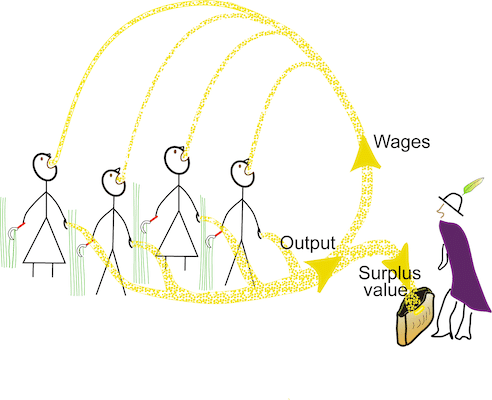

With entrenched political power wielding authority over or directing the behavior of rakyat2, whether in economic, social lives or cultural, the accumulation of capital to the ruling class continues expanding. The political economy of Malaysia needs to be analysed on a class basis because it entails producing, expropriating, and distributing surplus value of rakyat2 labour – by rent seekers in collusion with monopoly-capital.

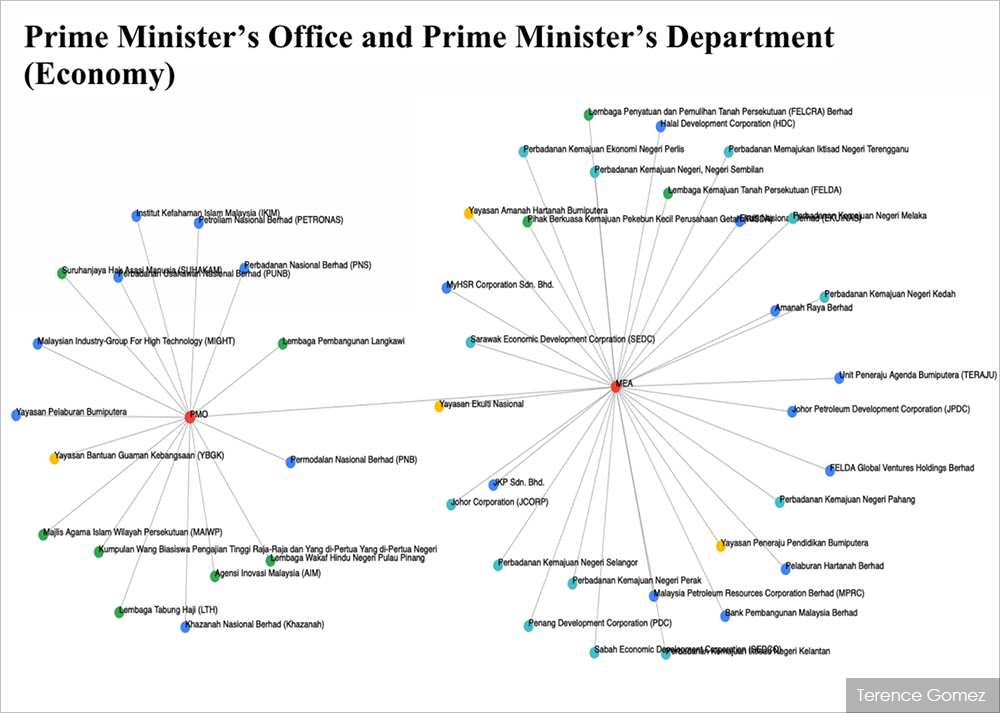

Under capitalism, the capitalists are dominant at each level of society, the proletarians are dominated at each and every sector of labouring activities. Where class existing at each economic, political, and ideological (or cultural) level, the class relationship to where dominating power ensues could be identified from the stronghold of clientelism and the ensuring political clientel relationship where ruling elites in, say United Malay National Organisation (UMNO) [place] had aligned with economic oligarchs [positions] in accepting rentier capitalism to sustain their hold on [power]. They adopt this clientelism as solicitations for votes at the grassroots level, allowing division-level ruling elites [place] the party patronage [position] and political [power] to effectively partisanizing them and ensuring ground-level officials with whom most voters interacted with are political party loyalists, (see Weiss 2020 and newmandala). The entrenched class even tried to own and control the banking sector just as government linked companies (GLCs) have administrative controls over various land distribution to landless cultivators. GLCs also have their hands full in many financial sectors including the Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) which is the investment arm of the Bumiputra Investment Foundation (YPB) under financialization capitalism :

5] LABOUR, CLASS AND ALIENATION

a) The political economy environment encourages local corporate capital colluding with external monopoly-capital towards continuous extracting surplus value from the labouring class. Through the application of global labour arbitrage where, as a result of the removal of or through the disintegration of barriers to international trade, jobs and industries have since moved to nations where labour and the cost of doing business is through workers’ low-pay and where operational costs are inexpensive, respectively, thus creating a rentier capitalism class to enlarge upon capital accumulation by the TNCs.

b) With the introduction of computerisation in the country during 1980s, and the inauguration of the Multimedia Supercorridor in Cyberjaya – more wide spread when the economy engages in e-commerce at the beginning of the twenty-first century – Workers in the digital-economy and zero-hour workers often found themselves underemployed, and alienated whether as the reserve army of labour looking for jobs or searching for unaffordable housing or as unsettling owners on Felda Venture Global’s FELDA plantations.

c) Now with the introduction of a system in infrastructural platform, likely it shall indeed expand and likely prolong the unemployment problems in the country because present education system has not engender nor energise an IT ecosystem to support such high-technology system where the main gainers are the digital lords and digital knights like Telekom’s TM as a monopoly GLC-clientel gainer just as in the pharmaceutical industry the privatised pharmaceutical firm Pharmanagia profited well during the Covid19 pandemic. In the public hospitals, owing to the compradore capitalists greeds and the adoption of a financialization capitalism model, there is an unequal access and inequity healthcare services throughout the country- whether in Sabah or Sarawak. There should be a national initiative towards equity and equality access to healthcare provision, more urgently now with the rollout of Covid19 vaccines, the distribution process could be disrupted by the challenges in the monopoly supply chain, (see codeblue, bridgetwelsh, aliran 2019; see also Jomo on vaccine nationalism and vaccine apartheid).

6] CIRCUITRY OF CAPITAL

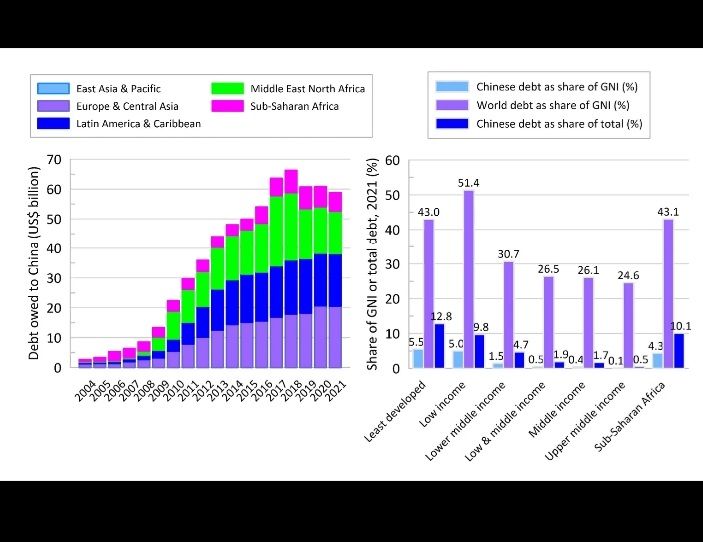

a) The chaining to the neo-colonialism economic architecture linking to extractive value chain benefitting Global North monopoly capitalism that encourages penetration of neo-imperialism with financialization capitalism which has gourged national resources is the circuitry of capitalism that indebted national sovereign wealth.

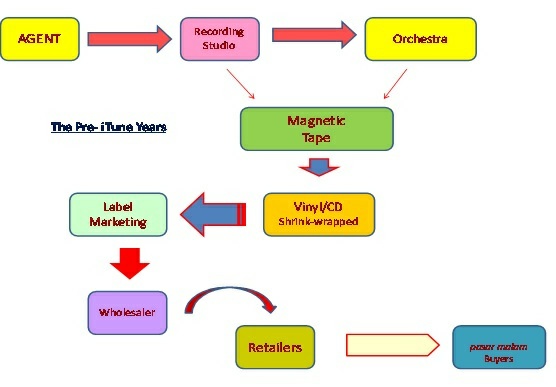

b) The circuitry of capital that tied to Global North monopoly-capitalism by commodity chaining in the acquiring, production and distribution of raw materials into as finished commodities to be channelled to various external marketspace has not endowed, despite urged to aim high by World Bank, the national economy towards wealth creation for rakyat2 but solidify in the country clientel capitalism. In partucular, present ruling regimes are adopting clientel-capitalism to colonialise the minds of the unrepresented destitutes in order to retain and sustain political power yet without much spread effect to be equally shared.

Indeed, the top 1% own 45% of all global personal wealth; 10% own 82%; whereas the bottom 50% own less than 1% according to Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report on the household wealth of 5.2 billion people across the world.

c) In a globalised world, activities are involved in the production of goods and services and later their supply, distribution, and post-sales activities are coordinated across geographical destinations; there are values in these activities because capital follows these processes during circuitry. Global Value Chain (GVC) has generated much inequalities that is dissonance with poverty’s poors with approaches of unequal exchange. Most unfortunately, the GVC world also enhances the dominance of transnational corporations (TNCs), concentrates wealth, represses the incomes of supplier firms in developing countries, and creates many bad jobs (degrading, dirty, dangerous) that demand foreign labour intake with deleterious outcomes for local workers, but if they do protest on working conditions whether through go-slow or collective strikes, union busting by TNCs becomes the directive norms.

7] ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS

a) Since the accumulation of capital is paramount to the owners of capital, their prime objective is to obtain their returns of investment within a short period so they can accumulate profits faster. As a result, investors do not consider long term impacts of their actions on the environment nor Mother Earth’s biosphere, (see Ian Angus, Earth Science and Ecological Marxism)

b) Marx’s central concepts of the “universal metabolism of nature,” “social metabolism,” and the metabolic “rift” to define the ecological worldview, (Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3, London: Penguin, 1981), 949; Marx and Engels, Collected Works, vol. 30, 54–66) means that an understanding of ecological economics and ecosocialism development for nation is a necessity towards attaining ecologically Engels.

c) The deforestation of Borneo rich hinterlands with the construction of the Pan Borneo Highway, the radioactive contamination by rare earth Lynas, the suphuric discharge in Mamut copper mine and cyanidation of Raub Australian Gold Mine bear testimonials that human must bear ecosocialism responsibility to our planetary well-being to Mother Earth.

8] MADANI Malaysia

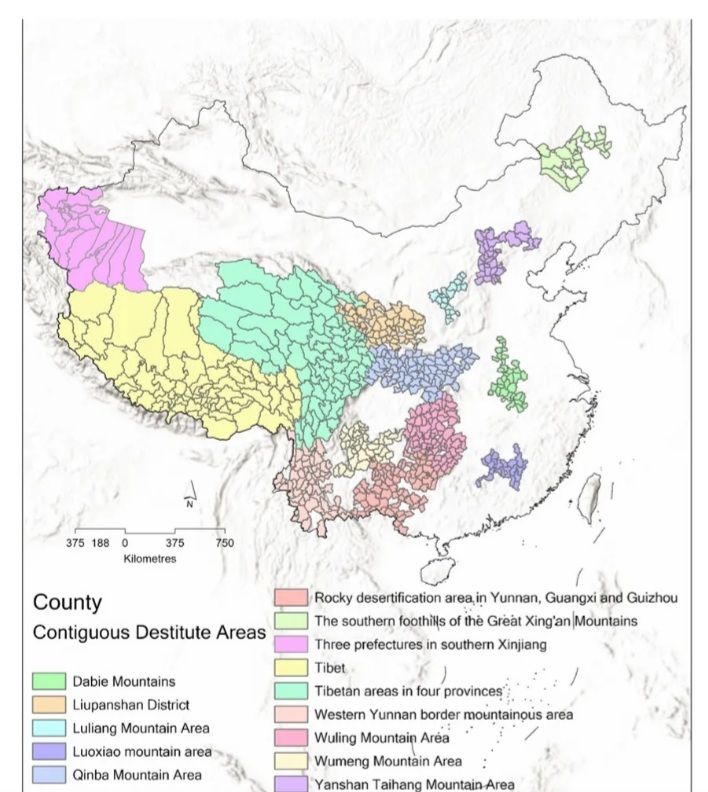

Post-GE15, there is a serial of articles on MADANI economy Malaysia covering The Script on capital accumulation and labour exploitation relations besides other economic elements in The Naratives and critical observations therein with The Conversation. The main components in a Madani Malaysia economic development are covered by various aspects like the vision of a democratic islamic view on politico-economic development as well as the parameters require to execute the endeavour: financial requirements and means to secure them; the approaches including the Targeted Area in Poverty Alleviation Objectives (TAPAO), and the method to implement the PRAXIS, those identifiable constraining factors in deliverance from neoliberal policies as advocated by the World Bank/IMF to the inefficiency in the class-stratified public sector besides the limitations in fiscal tools to minimise debts and will power to restructure the government-link companies and their ensuing odious practices.

The geoeconomic challenges of a Madani economy Malaysia is amplified whilst an alternative community-based organisation based on socialism with a Malaysian characteristic is proposed.

9] Other than the inherent weaknesses of capitalism are examined, the alternative economic model in socialism practice is proposed using US-CHINA case studies in an Incremental Capital Output Ratio analysis.

10] EARLY MALAYSIAN TRILOGY

Acknowledging that human evolution helps us to understand the biological and cultural expressions of these First People, with far-reaching implications for Man’s shared welfare, there is a need on the extension, and explanation, of a Malaysian consciousness towards a national identity, and firming the nation-bonding.

Part I: The Early Malaysians

The oldest evidence of early human habitation in Malaysia was discovered in 2008 when stone hand-axes were unearthed in the historical site of Lenggong dating back 1.83 million years. Also in Malaysia, the earliest discovery of a 40,000-year human skull was found in the Niah Caves of Sarawak, besides new archaeological discoveries in the Lembah Bujang area in Sungei Petani.

Therefore, only by being conscious about the role of various communities – with different ethnic, race and creed – that defines our Malaysian nation can help to challenge power holders who had distorted and reconstructed history based on self ethnocapital class interests by seducing society according to ethnicity, race and religion, (see Lim Teck Ghee 2021, Cheah Boon Kheng 1996).

EPILOGUE

One possible solution to these crises of capitalism, and that is, the demise of capitalism itself.

GLOSSARY TERMS

1mdb Malaysia sovereign fund heisted

AI Anwar Ibrahim; artificial intelligence

agency house British entity acting as an intermediary to merchants or cohort of traders in colonial England

alienation the process whereby the worker is made to feel foreign to the products of his/her own labour or the process of labour and a self consciousness on self-estrangement during the labouring effort

B40 represents the bottom 40% of income Malaysia

black swan an unpredictable or unforeseen event, typically one with extreme consequences

bourgeoisie rose at the end of the eighteenth century, and (in Marxist contexts) the capitalist class who own most of society’s wealth and means of production

bumiputra (Jawi: بوميڤوترا) is a term used in Malaysia to describe Malays and Orang Asli or indigenous peoples of Malaysia or Southeast Asia; officially, it recognised the “special position” of the Malays provided in the Constitution of Malaysia, in particular Article 153

capital wealth in the form of money or other assets owned by a person or organization to further generate higher rates of return to the initial capital outlay thereby creating capital accumulation https://youtu.be/DwyYzewiGh8

capital accumulation is an increase in assets from investments or profits and is one of the building blocks of a capitalist economy (capitalism) where the goal is to increase the value of an initial investment as a return on investment, whether that be through appreciation, rent, capital gains, or interest (that could also be part of financialization capitalism)

capitalism an economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state

capitalist class the group of people who own the means of production and employ workers

class where the ruling class (bourgeoisie) who own the means of production and the working class (proletariat) who are exploited

class struggle where in any society there is tension or antagonism that requires such conflict to be resolved

clientel capitalism is rent-seeking capital in the monopolization of access to any kind of property (physical, financial, intellectual, etc.) to gain significant amounts of returns without any contribution to society

compradore capitalist an entrepreneur in colonial or THIRD WORLD countries who accumulates capital through acting as intermediary between indigenous producers and foreign merchants

coronavirus capitalism is a particular type of Malaysian corporate capitalism infecting and destabilising the national economy through cronyism and/or ethnocratic empowerment; can transmit transnationally across the South China Sea to the states of Sarawak and Sabah

cronyism the appointment of friends and associates to positions of authority, without proper regard to their qualifications

dawn raid the returning and retaining of British agency houses assets and resources to Malaysia; see Guthrie Dawn Raid

digital labour e-commerce workers

digital transactions seamless system involving one or more participants, where such transactions are effected without the need for cash

economic nationalism favors state interventionism over other market mechanisms, with policies such as domestic control of the national economy, labor, and capital formation

ethnocracy political structure in which the state apparatus is controlled by a dominant ethnic group (or groups) to further its interests, power and resources

ethnocapital where bumiputera is advancing the Malay community with capital to the disfranchisement of others

epidemiological relating to the branch of medicine which deals with the incidence, distribution, and control of diseases

FELDA the Federal Land Development Authority – a Malaysian government agency to handle the resettlement of rural poor and smallholders into newly developed areas to plant, grow and harvest cash crops like palm oil and rubber

FGV Felda Global Venture is the global, diversified and sustainable integrated agri-business corporatized from FELDA settlers’ schemes

FTZ free trade zone: a geographic area where goods are imported, stored, handled, manufactured, or reconfigured and re-exported without subjecting to customs duty

financialization development of financial capitalism during the 1980s to present, in which debt-to-equity ratios increased and financial services (derivatives. hire-purchases, insurance, leasings, rents, digital transactions and interests) accounted for an increasing share of national income relative to other sectors

fiscal stimulus (packages) a government cuts taxes or increases its spending or just gives out any money in a bid to revive the economy and placate rakyat

globalization the process by which businesses or other organizations develop international influence or start operating on an international scale

global capital is the interlinking of various investment exchanges around the world that enable individuals and entities to buy and sell financial securities and digital transactions at international level

global labor arbitrage is an economic phenomenon where, as a result of the removal of or disintegration of barriers to international trade, jobs move to nations where labor and the cost of doing business is inexpensive and/or impoverished labor moves to nations with higher paying jobs.

global north refers to those developed societies of Europe and north America with dominance of world trade and politics

global south identifying countries with one side of the underlying global North–South divide, the other side being the countries of the Global North; underdeveloped and developing countries which are not part of global north

global oligopolistic capitalism, in which finance capital has come to dominate worldwide production and distribution

global value chain in a globalised world, activities are involved in the production of goods and services and later their supply, distribution, and post-sales activities are coordinated across geographical destinations; there are values in these chained activities that are not accrued to labour in the producing countries

kleptocracy a government whose corrupt leaders (kleptocrats) use political power to appropriate the wealth of their nation, typically by embezzling or misappropriating government funds

labouring class comprises those engaged in waged or salaried labour, especially in manual-labour occupations and industrial work

landless untitled cultivators and farmers, indebted FELDA settlers and unsettled natives in Sarawak and Sabah

M40 representing the middle 40% of income earners in Malaysia

malay dilemma is the particular question on the dilemmas of many a malay not understanding what are the problems of the malay community that has to be examined and analysed by a Dr. Mohammed Mahathir

means of production also termed as capital good, are physical and non-financial inputs used in the production of goods and services with economic value

monopoly capital greater centralization and concentration of capital by conglomerate of businesses along with the financial domination of industry

neoliberalism market-oriented reform policies through eliminating price controls, deregulating capital markets, lowering trade barriers besides reducing state influence with privatisation in the economy

nep new economic policy initiated in 1970 sought to ‘eradicate poverty’ and ‘restructure society to eliminate the identification of race with economic function’ in order to create the conditions for national unity

ngo non-government organisations

neo-colonialism use of economic, political, cultural, or other pressures to control or influence other countries, especially former dependencies https://wordpress.com/read/blogs/58770018/posts/264

neo-imperialism using cultural, commercial and/or political power and influence to dominate smaller countries. Neoimperialism is the specific contemporary phase of historical development that features the economic globalization and financialization of monopoly capitalism.

neo-liberalism economics market-oriented reform policies such as “eliminating price controls, deregulating capital markets, lowering trade barriers” and reducing state influence in the economy, especially through privatization and austerity.

oligarchic alliance an international monopoly alliance of oligarchic capitalism, featuring one hegemonic ruler and several other great powers, has come into being and provides the economic foundation for the money politics, vulgar culture, and military threats that exploit and oppress on the basis of the monopoly

pandemic an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide often as a result of global capital that drove the deforestation for economic activities exposing emergence of new pathogens

political islam the ideology of Ketuanan Melayu Islam (Malay Islam Supremacy)

precarious labour to describe non-standard or temporary employment that may be poorly paid, insecure, unprotected, and unable to support a household

privatisation the transfer of businesses, industries or services from public ownership and or control to private ownership and control.

rakyat folks or ordinary people of Malaysia

rentier capitalism monopolization of access to any kind of property (physical, financial, intellectual, etc.) and gaining significant amounts of profit without contribution to society

rukunegara https://wordpress.com/read/feeds/15271425/posts/2891028545

socialism where there is no ownership nor private-property income, but when labour work for a share of firm’s profits or collect a share of dividends from society’s wealth which is equally shared

supply chain is a network between a company and its suppliers to produce and distribute a specific product or service. The entities in the supply chains include producers, vendors, warehouses, transportation companies, distribution centers, and retailers

surplus value the excess of value produced by the labour of workers over the wages they are paid

T20 represents the top 20% of income earners in Malaysia

tasik utara student movements’ campaign for eradication of rakyat rural poverty

third world countries included nations in Asia and Africa that were not aligned with either the United States or the Soviet Union

transnational an entity going beyond national boundaries or interests; often, the term MNC multinational corporation is used where it is a large organisation incorporated in one country that produces or sells goods or services in various countries. The two main characteristics of MNCs are their large size and the fact that their worldwide activities are centrally controlled by the parent companies

value chain is formed of primary activities that add value to the final product directly and support activities that add value indirectly

zero hour type of employment contract between an employer and worker whereby the employer is not obliged to provide any minimum number of working hours to the employee

Sun Liping 孙立平 | Tsinghua University Department of Sociology professorThe era of large-scale concentrated consumption experienced previously is basically over, said Sun in a speech on 14 April 2024. The PRC economy is in a period of contraction, and the consumer sector too is at a turning point. In conventional consumption’s current stage of gradually dividing, he said, ‘the poor cannot afford, the middle class does not dare, and the rich do not know what to consume’ has become a common impression. Given differentiating consumption, and the background of economic contraction, consumption of society as a whole faces a downward trend. Overcapacity is just a manifestation of this reality.Born in a Hebei village in 1959, Sun studied journalism at Peking University 1978–81, taking up sociology at Nankai University 1981–83. A journalist for some years, he joined Tsinghua University in 1993. He famously helped advise a younger Xi Jinping’s PhD dissertation, the resulting political capital arguably allowing him to test the limits of intellectual expression. His bestselling 1996 book, The Road to Modernisation, argued that politics had been outpaced by economic growth, brewing corruption, inequity, and unrest. With over 300 other intellectuals, Sun co-signed the ‘Charter 08’ open letter to the Party, urging political reform. He warned Caijing Magazine’s annual Forecasting and Strategy conference in 2013 of a ‘crisis of legitimacy.’ Widely reported, this caused a stir. Other notable works include Social Reconstruction (2009), China’s Political Reform (2011), and Crisis of Legitimacy (2013).

Sun Liping 孙立平 | Tsinghua University Department of Sociology professorThe era of large-scale concentrated consumption experienced previously is basically over, said Sun in a speech on 14 April 2024. The PRC economy is in a period of contraction, and the consumer sector too is at a turning point. In conventional consumption’s current stage of gradually dividing, he said, ‘the poor cannot afford, the middle class does not dare, and the rich do not know what to consume’ has become a common impression. Given differentiating consumption, and the background of economic contraction, consumption of society as a whole faces a downward trend. Overcapacity is just a manifestation of this reality.Born in a Hebei village in 1959, Sun studied journalism at Peking University 1978–81, taking up sociology at Nankai University 1981–83. A journalist for some years, he joined Tsinghua University in 1993. He famously helped advise a younger Xi Jinping’s PhD dissertation, the resulting political capital arguably allowing him to test the limits of intellectual expression. His bestselling 1996 book, The Road to Modernisation, argued that politics had been outpaced by economic growth, brewing corruption, inequity, and unrest. With over 300 other intellectuals, Sun co-signed the ‘Charter 08’ open letter to the Party, urging political reform. He warned Caijing Magazine’s annual Forecasting and Strategy conference in 2013 of a ‘crisis of legitimacy.’ Widely reported, this caused a stir. Other notable works include Social Reconstruction (2009), China’s Political Reform (2011), and Crisis of Legitimacy (2013).

You must be logged in to post a comment.