23/06/2023

collective on geoeconomics

Prologue

From The Quest for Growth (World Bank, 2016), and to Surge Ahead (World Bank 2021), the country is still, catastrophically, mired and entrapped within capitalism crisis to crisis in a struggle to Catching Up, (World Bank, 2022) among ASEAN peers:

1] THE MEN

The Madani Economic Narrative is a new economic developmental approach aligned with the Madani concept on sustainability, care and compassion, respect, innnovation, prosperity and trust (SCRIPT).

The Madani objective is to provide each ministry and agency with directives on the implementation of the unity government various – PMO’s Finance, the Ecomomics Ministry, MoHR, MITI – and varied economic plans on fiscal stability, economic growth, labour reforms and industrialisation under an e-commerce economy.

The prime goals of these economic plans are the creation of a high valued yet sustainable (within a defined digital) economy whilst concurrently, expanding social welfare protections to rakyat² by empowering them through reforming the labour market process.

That the new MEN shall only be awaken and take a presentation stroll in August 2023 indicates that this living specimen is, maybe, a precarity in an expiring economy.

2] THE PROBLEMS

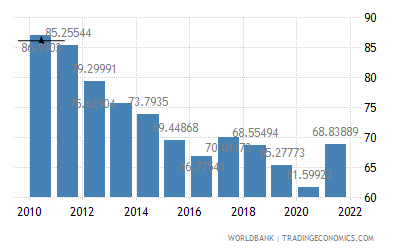

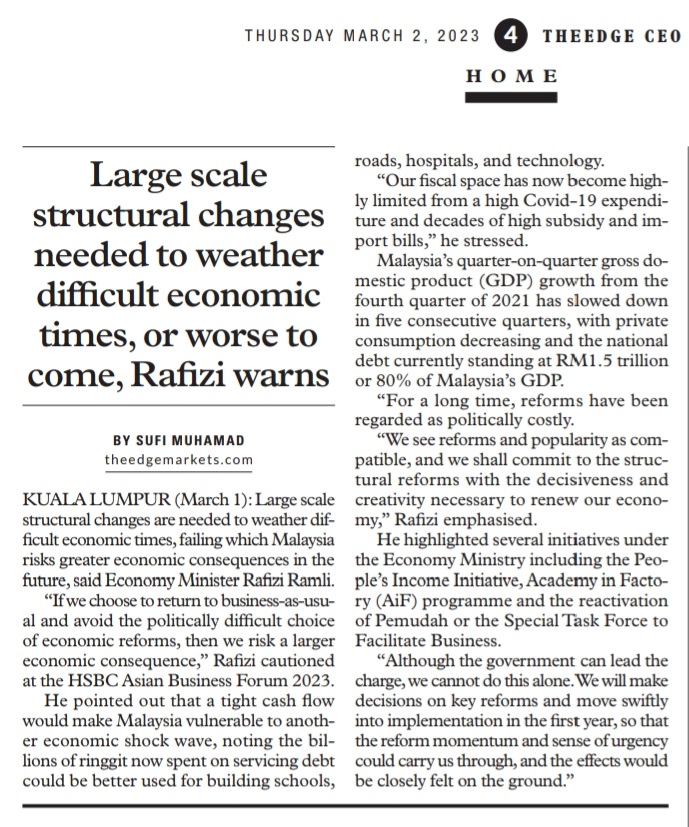

i) As a trading nation, but with a declining factor in GDP, the country is in dire state of an existential eclipsing economy confronted by cost-of-living inflationary trends and slack in manufacturing capability in a competitive global domain, a youth unemployment rate nearing 12%, and female labour below most ASEAN countries, and a public sector effective productive yet to be improved, and enhanced upon, as its captured place, position and power are entrenched.

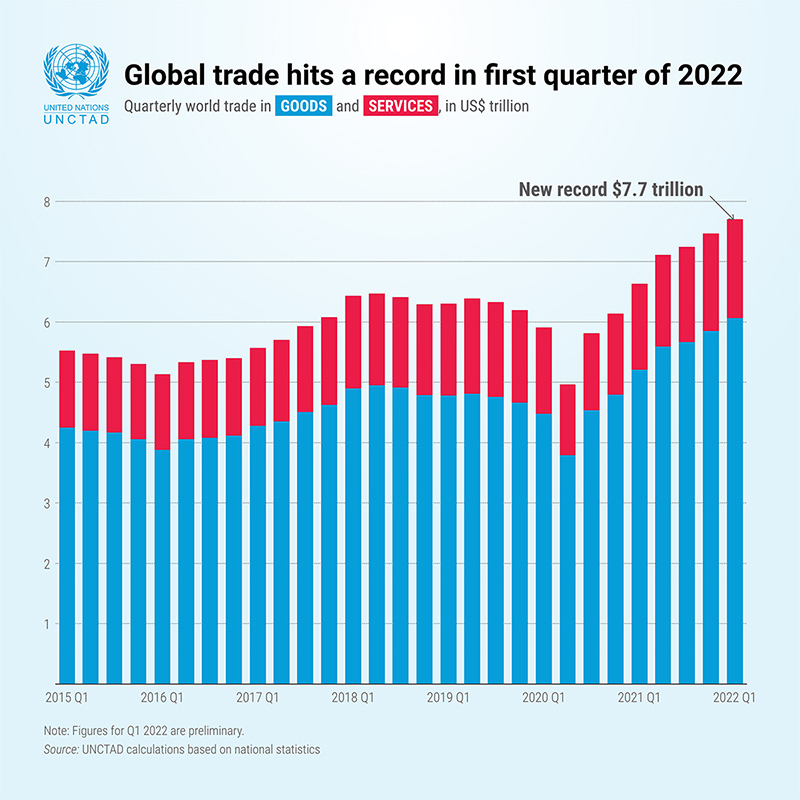

Exports of goods and services in Malaysia was reported at 68.84 % of GDP in 2021, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators.

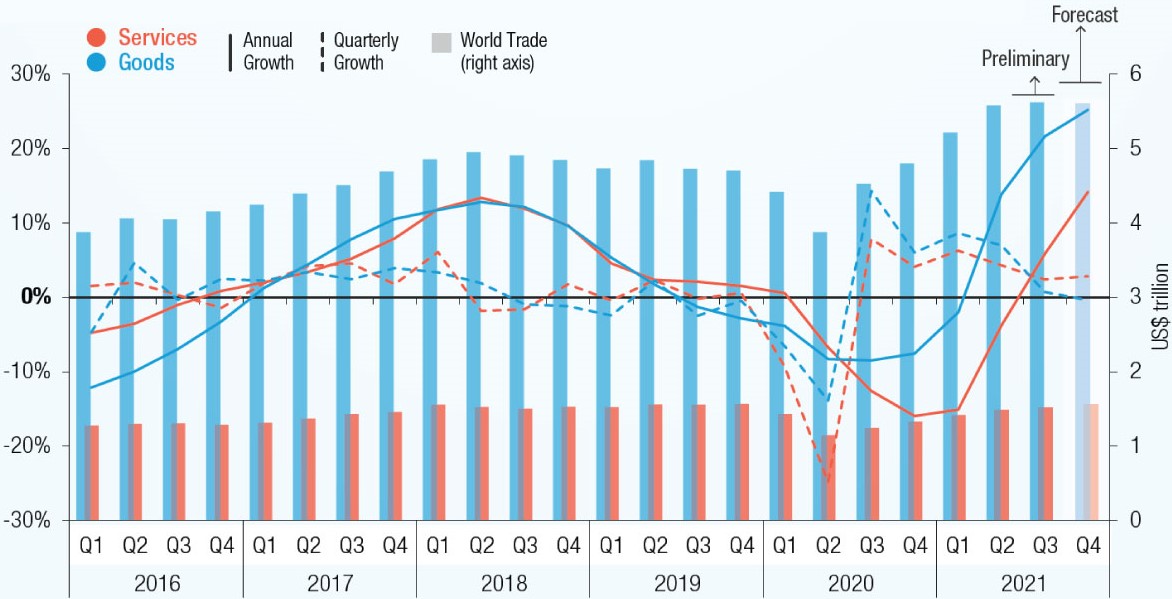

The 0.7% fall in Malaysia’s exports in May 2023 compared with a year ago portends downside risks pointing to a weak export growth momentum for the remaining months of the year – even as Malaysia’s national debt now at RM1. 5 trillion, or over 80% of GDP – whence the ringgit is under exchange rate pressure, and may weaken further against the US dollar to as steep as 4.7500 by the third quarter of 2023, (nst 30/05/2023).

United Overseas Bank (M) Bhd senior economist Julia Goh said despite the narrower year-to-date contraction in exports, global demand has yet to show signs of rebounding. This is concurred by OCBC Banking Group Ltd senior Asean economist Lavanya Venkateswaran who said the contraction in exports was broadly in line with the bank’s expectation. In fact, the combined April/May data confirms that an external sector slowdown is already and duly underway, (theedgemalaysia 20/06/2023).

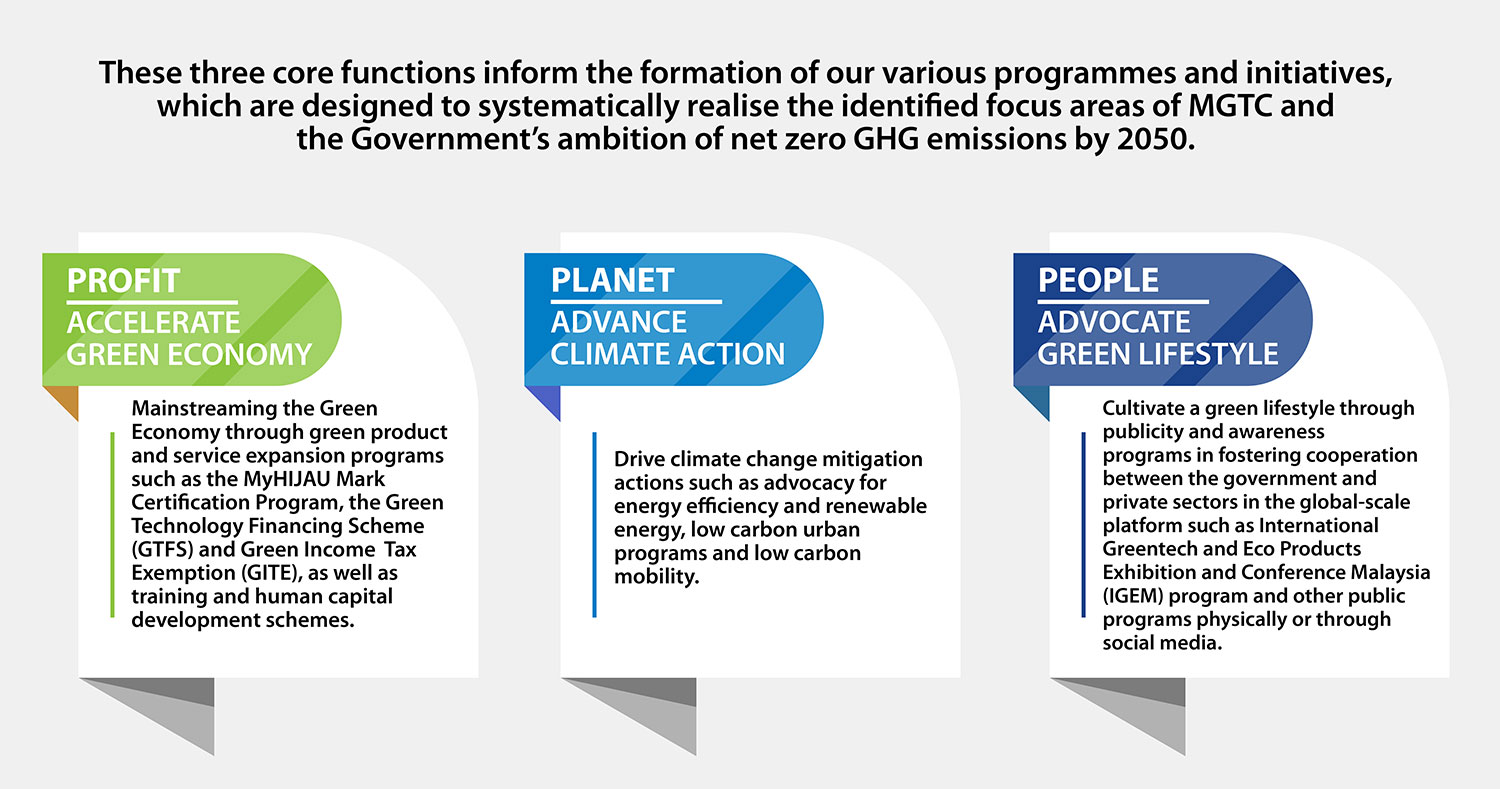

The strategic economic option is through an adequate, and appropriate, Industry 4.0 Initiative with existing deficiencies to be ratified and organizational processes restructured, including upskilling of workers, taking into account that feudal capitalism is meshed in the country’s present Digitalisation Capitalism environment where the capital and labour factors have yet to be reconciled on a careful trust and compassionate basis to ensue a common wealth sharing developmental effort – if the country insistence upon sustaining a prosperous and respectful society has to be maintained.

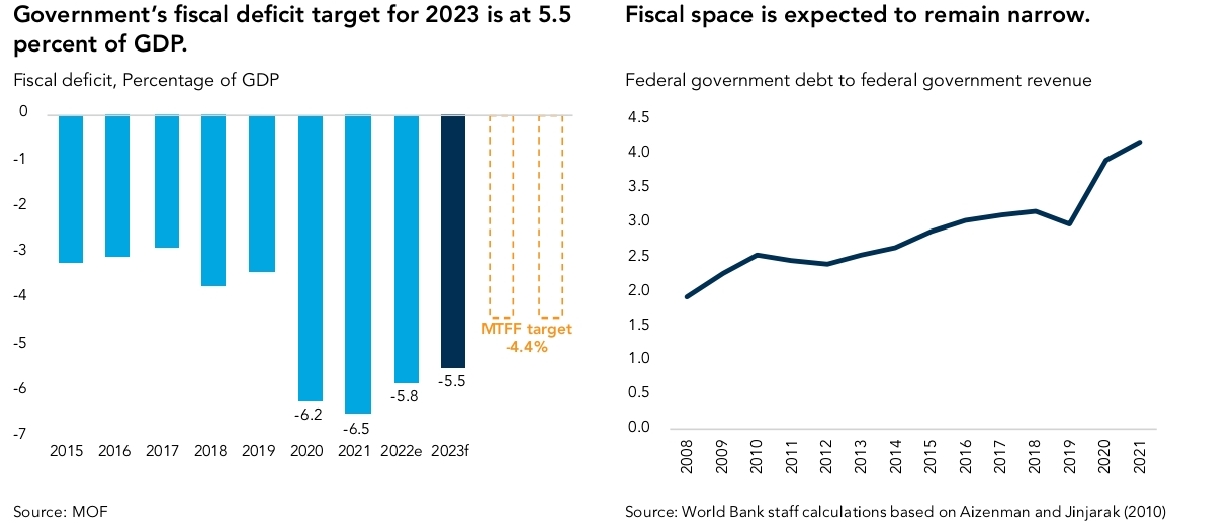

ii) With government revenue already projected to remain low and structural expenditures still increasing high, this has led to further narrowing of Malaysia’s fiscal space (see right chart below):

Using the ratio of the Federal Government Debt to the revenue collection as a reference point, the World Bank has indicated that Malaysia’s fiscal space has indeed narrowed since 2012 and has in fact became even tighter post-pandemic. Indeed, the current fiscal consolidation strategy – via spending reduction – is, to many national economists and political analysts, (bfm.my, IDEAS, theedgemarkets, O2 Survey) rather challenging, given the current tight spending domain.

The way out is selectively, and strategically, in choosing some of the options available in financing the economic development of the country, (see STORM 2023, Debts Financing towards Progressive Economic Development).

iii) Since the Olin Liu’s IMF Report is there now a structural approach to national economic development that is more strategic and formative in dealing with politico-economic realities faced by the nation in totality. However, the tasks ahead are still daunting, (see STORM 2023, Towards structuring economic development with sustainability).

Firstly, the national coffer is depleting: both from odious transactional practices through the decades, supported by the public sector with dastard nature of kleptocractic and korupsi practices. As such, the performance criteria to spur economic development have not been met. More than ever, the government should consider seriously to increase its revenue base by improving and innovating the tax system. With the uncalled expansion of government-linked companies and public authorities in the 1970s and 1980s, the nation is facing difficulties in maintaining and sustaining these parasite entities. One option is to raise the Goods and Services Tax (GST), but with the provisio where some of the GST is redirected to lower-income groups to improve their living conditions.

Secondly, ruling regimes should not perpetually rely on Petronas for funds. Instead, like other resource-rich countries, the nation should setup an investment fund which, in the long run will provide revenue to assist in its budget planning and allocation. With Malaysia petroleum reserves for oil and gas resources projected – according to the Reserve Life Index – to last another 15 years only, Malaysia’s probable and proven reserves of petroleum totalled 6.9 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The way foward is to optimise present petroleum resource and to stretch to over 40 years with high capital investment, new technology as well as more stable and competitive investment landscape.

Indeed, Emir Research consultancy has indicated that the country should strengthen the oil and gas (O&G) sector by enhancing the attractiveness of existing energy and petrochemical hubs, increasing and intensifying exploration in the South China Sea and offshore deepwater elsewhere in the world. The primary objective is to maximise outputs and include a more robust national stockpiling policy and stabilising infrastructure ecosystem in place. Under this approach, through diversification and expansion, the O&G sector can then be transformed. Petronas and its subsidiaries from an O&G base or oil and energy corporation into a global industrial conglomerate. In fact, Petronas should not be limited in expansion and investments on the energy and renewable enery business and assets, but also leading to renewable chemicals, petrochemicals, materials and other businesses.

Thirdly, the oil palm sector is likely to remain a major food oil for the world and as a base oil for various other products. The ‘core’ business shall be widened with a flexibility to quickly adapt to market forces and competitive disruptions. For once, palm oil mills generate biomass (from palm residues) that can be utilised for power generation and other renewables, such as fuels, chemicals and materials.

Fourthly, other economic sectors also need to move from lower value, high-volume commodities or simpler products to high-value end-user products to reap more from the value chains. An early de-industrialisation process in the 1990s had impaired the dynamics of the Electrical and Electronic sector in its contribution to higher commodity value chain.The E&E sector shall need to coordinate with present infrastructural platforms implementation processes to connect high-value commodity and value chains towards a digital economy.

Fifthly, institutional reforms are not only to pertinent major institutional structural reforms. There shall also be a demanding need in a good governance to ensure justice, equity, insuring talent availability is fully mobilised. Without these, policies and strategies will not be successfully or sustainably implemented. Therefore, policies must become needs based instead of previous kleptocractic ethnocapital hangovers with discriminatory, arbitrary or very not infrequently on a knee-jerk non-visionary reaction to developmental effort.

2] THE ISSUES

Nested within a neocolonial economy and following Lenin’s concepts of imperialism and international class conflict into the theory of economic growth and stagnation, the Global South, predominantly low developing countries (LDCs) were in the clutch of Global North economic and political domination, especially during the colonial period.

Therefore, the most enduring socio-economic and clientel ethnocapital colonialism issues in Malaysia are those related to the bumiputera and non-bumiputera term and the dichotomy, the compartmentalisation and polarity that has resulted since the term was introduced into the nation’s political lexicon and life. The contrived term and dichotomy was regarded as a deliberate and opportunistic strategy of the political and policy leadership to create a new political taxonomy to manage and control the political-administrative workings and socio-economic development of the country, and with the NEP to prioritise “UMNOputra” interests and dominance, predominantly and specifically to entrench bumiputera clientel ethnocapitalism.

Thus, post May 13, 1969, the country’s growth policies have shifted from strategies with an emphasis purely on economic growth toward a strategem focusing at combining growth with income inequality reduction between ethnic groups. This policy shift was formalized in the New Economic Policies (NEP) for the period 1971–1990 (see Economic Planning Unit, various years). The relationship between economic growth and ethnic diversity (Agostini et al., 2010, Gören, 2014, Iniguez-Montiel, 2014) is supported by a body of economic literature that finds that ethnic heterogeneity induces social conflicts and violence, which in turn, affects economic growth (see Easterly and Levine, 1997, Mauro, 1995, Montalvo and Reynal-Querol, 2005). The negative consequences of ethnic diversity imply that adequate policies are required to ensure that the benefits of any economic growth are equally shared among all ethnic groups, yet US$241 billion – equivalent to our national debt – had been poured into the Bumiputera agenda, an affirmative action plan to assist the majority race: a dependency debt-determined development syndrome.

Through ensuing as an economic entrenchment of the NEP construct (Woo 2015, James Chin 2016, KBN 2018, Khalid 2019, KRI 2020, Kua 2021) it is clearly divisive to the nation’s unity and a sense of belonging. The MEN as articulated is meant supposedly to eliminate these economic deformities.

Thirdly, the introduction of JAKIM to play a role in the economic advisory and planning performance only adds on the theological aspect in a secular society (Bakri; Tajuddin; Hunter) with a grim Islamic future upon non-muslims (Ignatius; Ramakrishnan), complicating the complexity on tasks in developmental execution (UNICEF; World Bank, 2022; and World Bank, 2019); STORM; Ramesh Chander, Murray Hunter, and Lim Teck Ghee) or is it that premier Anwar Ibrahim is closing a circle to an inadvertent post-ABIM script, (Mohktar). Nevertheless, the Madani precepts alone cannot merely serve as the pillars of a grand nation-building project when a rumah in a kampung built on stilted but capital-muddied foundation is prone to collapse.

Even if real prosperity, as Anwar Ibrahim believes, is enshrined in the Islamic concept of al falah (success, happiness and wellbeing), however, contrary to Marxism, Islam does not consider wealth as intrinsically evil. Also, unlike capitalism, Islam extends the concept to the entire community rather than restricts it to single individuals, stressing that abundance is a blessing to be shared. Whether the abundance sharing of a common wealth admidst diversity in geographical, creed and racial segments towards an ethos in socialism with a Malaysian characteristics has yet to be distinctively defined, and to be ably executed.

Finally, the continuance of a neoliberalism economic approaches post-independence only restrains the forward thrust in engendering a truly national developmental effort – whether and when they are a parcel of a suite in rural development, export-led industrialisation, a digitalisation e-economy but capitalism-wrapped, and now the Industry 4.0 Initiatives.

The neoliberal policy of the preceding regimes, with its emphasis on free market and privatisation, have only benefited a few elites, especially wealthy compradore capitals. The MEN sura conversation has, however, neglected to mention the roles and responsibilities of non-muslims who had contributed to the economic development of this country from the indenture labour in the rubber plantations, the pools of tin miners, the fruiting of the oil palm industry to the small manufacturing enterprises’ al amal and knowledge (spiritual, wisdom and scientific) in modern Malaysia. MEN has all the character of a muslim-Malay centric governance legacy. The existing economic praxis must be overhauled so that a just economic system that is equitable to all irrespective of race and creed while upholding the true spirit of democracy, individual rights, tolerance, gender equality and pluralism permeates right to the egalitarian soul of every rakyat-rakyat.

EPILOGUE

The MADANI ECONOMIC NARRATIVE needs to

big in vision, bold in objectives and a bravery to surmount the arduous developmental tasks in hand.

MEN not only requires to be sired – striving courageously in structuring institutional reform in an economic development ethos but to stir, and wrap-up, TAPAO in a nation-wide robust responsibility to achieve the desire goal of targeted area poverty alleviation ojectives otherwise it’s obviously an amen.

RELATED READINGS