7th June 2023

PROLOGUE

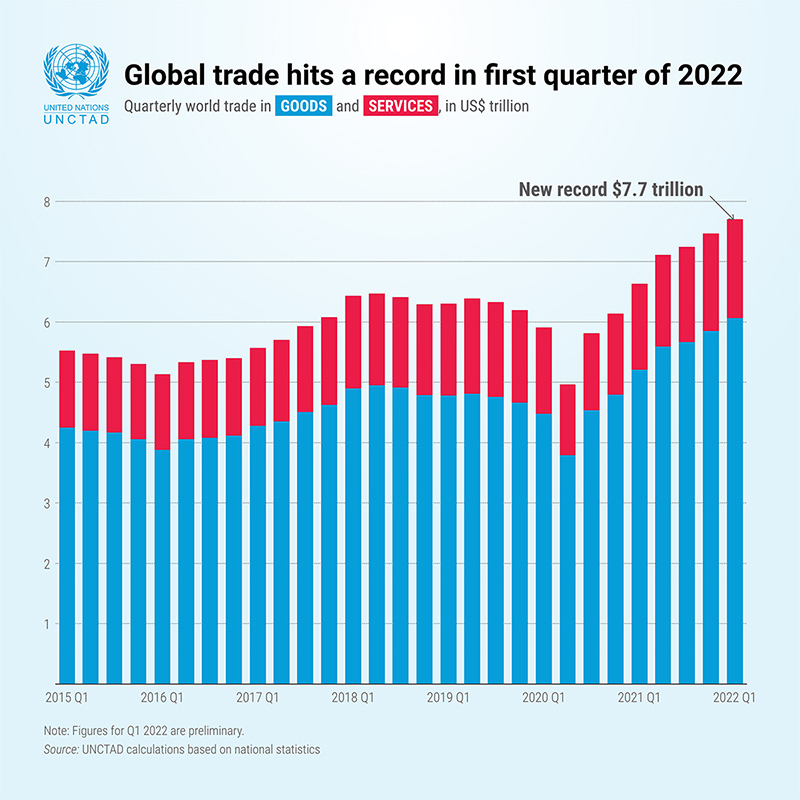

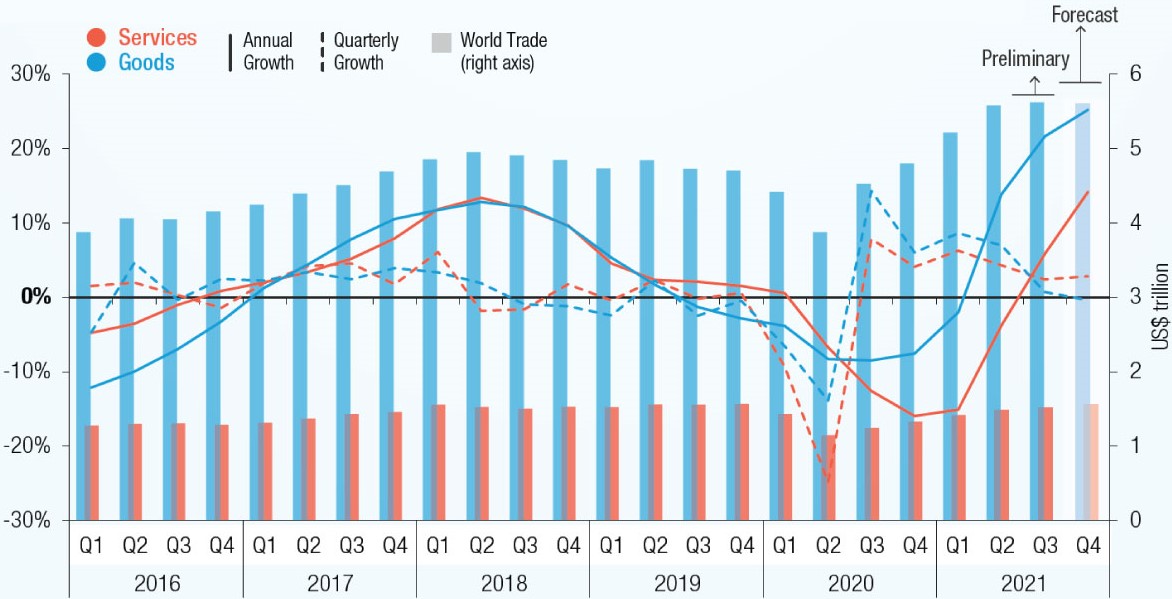

By the third quarter of 2022, the value of global trade in goods was well above the levels of same period in 2021 for both developing and developed countries.

Trade in goods grew 10% from last year to an estimated $25 trillion, due in part to higher energy prices. Services were up 15% to a record $7 trillion.

However, on a quarter-by-quarter basis, trade declined in all geographic regions – except for East Asia, which showed considerable resilience.

These situations come at a time when Global Trade could hit a record $32 trillion for 2022, but a slowdown that began in the second half of the year is expected to worsen in 2023 as geopolitical tensions and tight financial conditions persist, according to the latest Global Trade Update, published by UNCTAD on 13 December, 2022.

1. INTRODUCTION

Global supply chains are representives of the integrated structure of contemporary global capitalism, and any disruption to them often threatens the functioning of the system itself. The global supply chain, as an organic of capital and the organisation form of capitalism, is designed to raise the rate of surplus value labour extraction by capital. It facilitates the geographic transference of extracted value in arbitrage of labour from the Global South to the Global North. In a sense, global supply chains have contributed to dynamics of concentration in leading firms, and a marked shift in national income from labour to capital across much of the world.

However, presently, there is emerging a profound change of geostrategic dimension as great powers are retreating from the free trade system they have had created inducing a global supply chain shift. Great powers’ priorities are now refocusing and reording by global security concerns (Brookings Institute, 27/04/2023) which only sharpen capitalism from crises to crises. Unfortunately, the developing and emerging market economies, the ensuing global trading system becomes relentlessly reshaped, and affected, by these geopolitical priorities.

As an instance, in December 2022, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Japan, UK and US announced the formation of the Sustainable Critical Minerals Alliance, and the Group of Seven (G7) is initiating to invest in a secure supply of critical minerals. For developing economies of the world, this is a return to Cold War politics; more so, when leaders of countries such as Zaire (the Democratic Republic of the Congo) with strategic resources were courted by one side or the other, usually with devastating governance consequences.

Another grim suite of implementations is whereby the US and the EU introduced a combination of industrial policy, subsidies, and trade restrictions to motivate businesses at home and abroad to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In the US, it is the legislation of an Inflation Reduction Act which includes $400 billion in subsidies for renewable energy and electric vehicles that contain a minimum amount of North American parts. This provision has prompted returning US companies’ investment to the United States and has attracted foreign investors such as BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Stellantis, and Toyota. The EU, similarly, has launched the European Green Deal and a carbon border adjustment mechanism (scheduled to go into effect in October 2023), which imposes an “emissions tariff” on imports. For developing economies, the trade aspects of these initiatives look like “Fortress US” neo-mercantilism and “Fortress EU”. Indeed, the Global North rich countries which are fully responsible for the most climate-threatening emissions are locking others out of the fortresses their prosperity built.

2. CONSEQUENCES

The world economy may split into two rival blocs: the consequences are modeled in recent work by the WTO that projects welfare losses (or cumulative reductions in real income) as high as 12 percent in some regions, with the largest in the lower-income regions.

For developing economies, the uncertainties of the global trading system mean that most will want to negotiate trade, investment, aid, weapon purchases, and security from several sources. India and some African countries, among others, still rely heavily on Russian arms. Others depend on Russian energy, food, and fertilizer. Joining in sanctions against Russia for its cross-border incursion would cost them dearly. Many countries are strongly dependent on China’s aid, trade, and investment and are currently resorting to bailout loans from China. They also need markets in Europe and North America.

Thus, inevitably, the great powers’ new priorities are currently being set and implemented unilaterally. If great powers are more and more concerned with balancing their own political and economic interests without regard for longer-term mutual interests, including those of other countries, the latter need to remind them that their support is conditional on processes that include them.

In fact, the rest of the world is preparing itself with collection of self-reliance measures on the nonalignment principle to make sure that both superpowers relate to each other in a way that would not do more damages and to endanger all people of the world.

3. IMPLICATIONS

The country prime reliance on foreign cheap labour has become the biggest policy issue in the country’s aspirations to move up the value chain and to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). The country needs to design a new mission objective on exiting the middle-income trap. Otherwise, the proceeds of growth have not been equitably shared especially with increases in the cost-of-living outstripping incomes. In urban areas, where three-fourths of Malaysians reside, the UNICEF 2020 Report has shown that low income female-headed households are exceptionally vulnerable.

For a retarding development economy like Malaysia to attract quality FDI, the country should push domestic investment into strategic sectors to uplift national competitiveness in research and development, and more urgently to develop its own market niché. It is of utmost importance for Malaysia to develop its own competitive advantage that delivers sufficient return on equity to attract higher FDI into the country.

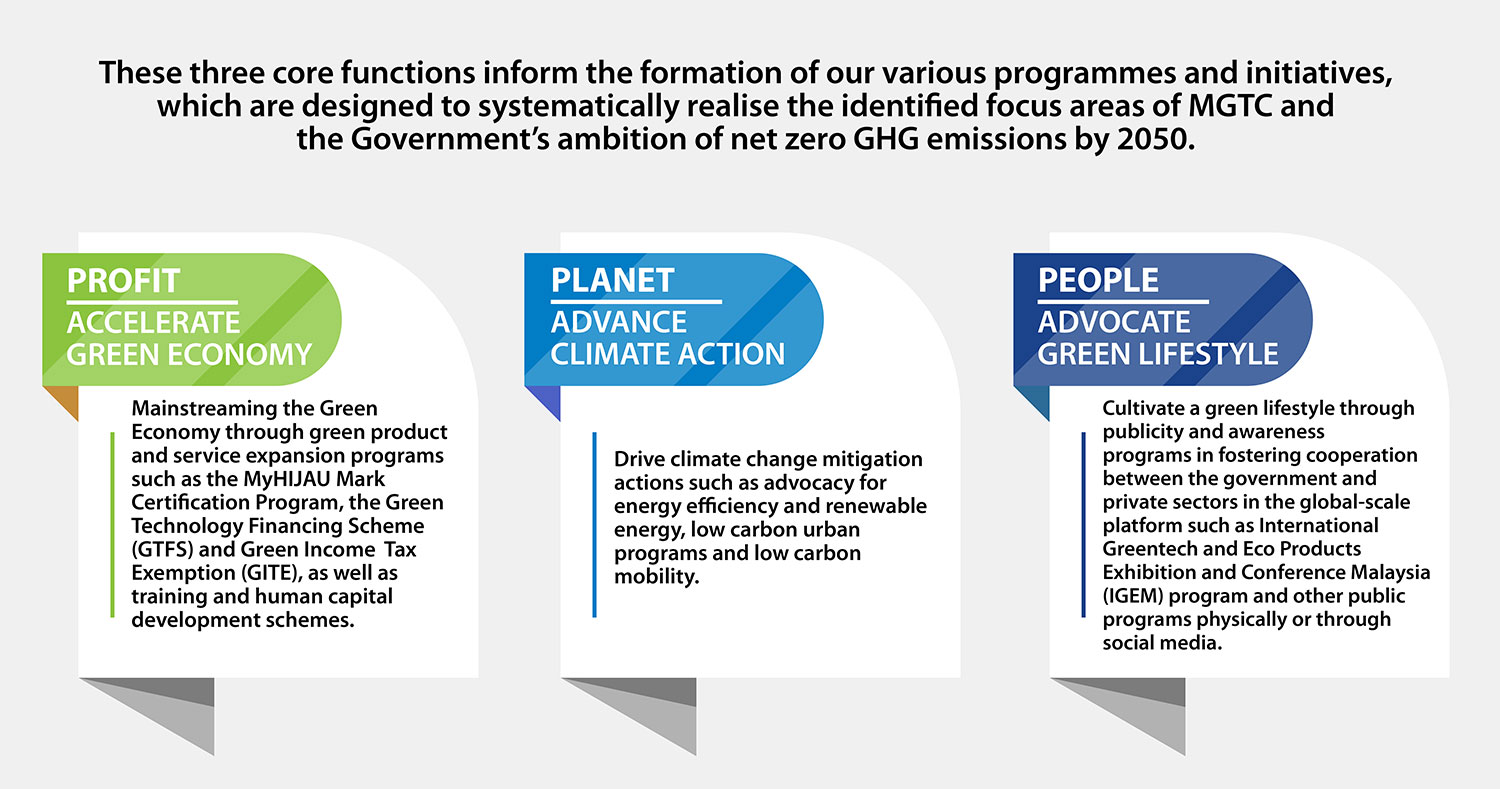

One of the prime national mission objective lies in green energy and technology as among the sectors that Malaysia should focus on in developing its own competitive Renewable Energy (RE) strengths, (Andrew Sheng, May 2023).

The six most common green forms are:

• Solar Power. This common type of renewable energy is usually produced using photovoltaic cells that capture sunlight and turn it into electricity;

• Wind Power;

• Hydropower;

• Geothermal Energy;

• Biomass; and

• Biofuels;

There are two (2) major types of renewable natural resources currently consumed in Malaysia; hydropower and solar energy.

The nation has already a RE Action plan established generation targets until 2050 when renewable energy should make 24% of the total energy mix, from 1% in 2011 and 9% in 2020 enabling more than 30 million tonnes of CO2 emissions to e avoided in line with the national target.

While UNCTAD has identified mitigation strategies – including diversification of suppliers, reshoring, near-shoring and friend-shoring – will likely affect global trade patterns in the coming year, however, the efforts towards building a greener global economy are expected to spur demand for environmentally sustainable products while reducing the demand for goods with high carbon content and for fossil fuels.

Emir Research consultancy has indicated that the country should strengthen the oil and gas (O&G) sector by enhancing the attractiveness of existing energy and petrochemical hubs, increasing and intensifying exploration in the South China Sea and offshore deepwater elsewhere in the world. The primary objective is to maximise outputs and include a more robust national stockpiling policy and stabilising infrastructure ecosystem in place.

Under this approach, through diversification and expansion, the O&G sector can then be transformed. Petronas and its subsidiaries shall transform from an O&G base or oil and energy corporation into a global industrial conglomerate. In fact, Petronas should not be limited in expansion and investments on the energy and renewable enery business and assets, but also leading to renewable chemicals, petrochemicals, materials and other businesses.

Thirdly, the oil palm sector is likely to remain a major food oil for the world and as a base oil for various other products. The ‘core’ business shall be widened with a flexibility to quickly adapt to market forces and competitive disruptions. For once, palm oil mills generate biomass (from palm residues) that can be utilised for power generation and other renewables, such as fuels, chemicals and materials.

EPILOGUE

The ongoing tightening of financial conditions is expected to further heighten pressure on highly indebted governments, amplifying vulnerabilities and negatively affecting investments and international trade flows.

Even as the global trade is slowing down

more than ever, the efforts towards rebuilding a greener global economy should be undertaken to spur demand for environmentally sustainable products, while reducing the demand for goods with high carbon content and for fossil fuels.

This is where Malaysia has to accept, adopt and be adaptable to a structural institutional reform on economic development in the decades ahead to be SIRED.