collated by, and collaborated with, the Collective of Geoeconomics

18/04/24

INTRODUCTION

The world economy is confronting a situational environment where the Middle East North Africa (MENA) region and the Ukrainian cross-border conflicts continuance are serving a sobering reality of geopolitical dimensions affecting geoeconomics realities. The escalation of tension in the Middle East combined with growing instability about Ukraine demonstrates once again how significant geopolitical decisions impact upon geoeconomics policies under calamity of capitalism regime.

The global growth rate — if one takes out the cyclical ups and downs — has slowed steadily since the 2008-09 global financial crisis (GFC’08). However, it is concurred that without policy intervention and leveraging emerging technologies, the stronger growth rates of the past are more unlikely to return.

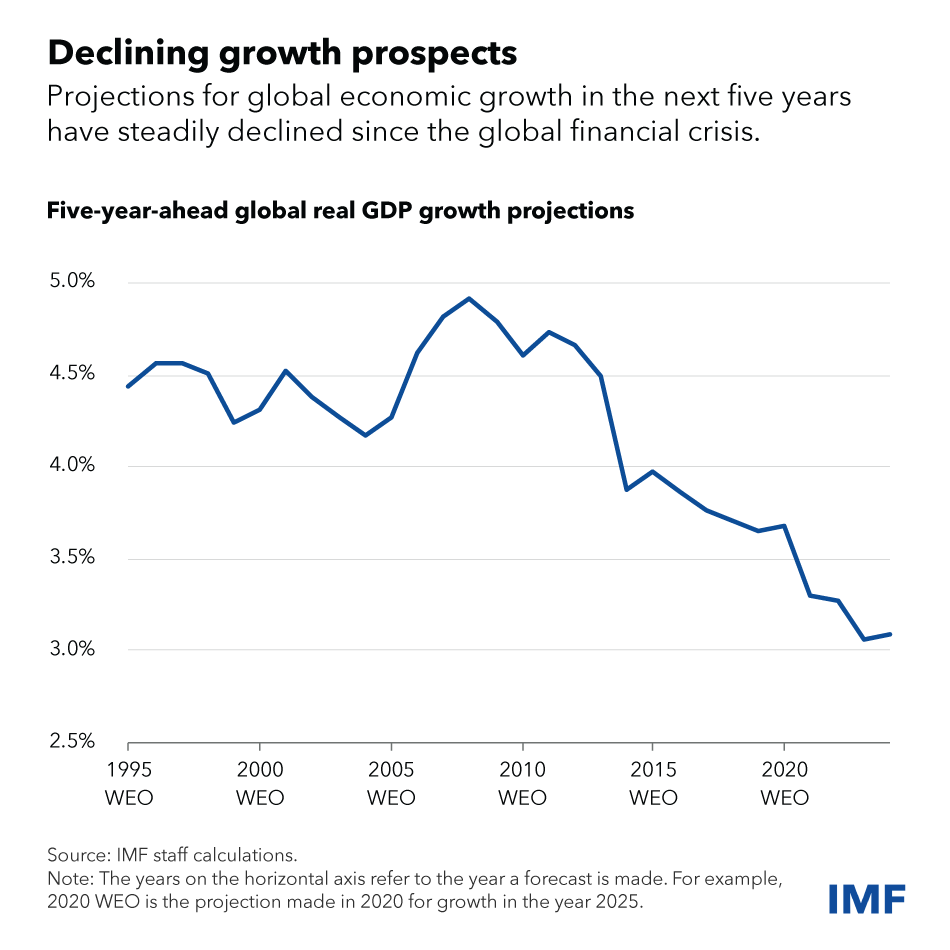

It can also be fairly stated that shrouded with several headwinds, future growth prospects are where capitalism is shoved into a calamity mode. Global growth will slow to just above 3 percent by 2029, according to five-year ahead projections in an IMF latest World Economic Outlook. The IMF analysis shows that growth could drop by about a percentage point below the pre-pandemic (2000-19) average by the end of the decade. This threatens to reverse improvements to living standards, and the unevenness of the slowdown between richer and poorer nations could limit the prospects for global income convergence.

Indeed, the latest IMF forecast for global growth five years from now – at 3.1 percent –is at its lowest in decades. The pace of convergence toward higher living standards for middle- and lower-income countries has slowed, implying a persistence in global economic disparities. …dimmer prospects for growth in China and other large emerging market economies, given their increasing share of the global economy, will weigh on the prospects of trading partners.

A persistent low-growth scenario, combined with high interest rates, could more likely than ever insert debt sustainability at risk whereby restricting the government’s capacity to counter economic slowdowns and invest in social welfare or environmental initiatives.

Further, there are indications in the expectations of a weaker growth rate that would- and could – discourage more investment in capital and technologies, possibly even deepening a capitalism slowdown.

All this is accentuated, and exacerbated, by strong headwinds from geoeconomic fragmentation, and harmful unilateral trade and industrial policies.

Here, the Collective on Geoeconomics (CoG) asserts that in the last two decades of the twentieth century, the world has witnessed the development and expansion of commercial, productive, and financial globalisation. This new phase in the world economy was marked by increased trade in goods and services, greater international participation in the productive operations of transnational companies, and the intense circulation of capital at the international level in a new dynamic of world capitalism. Faced with the demands of financial capital – the dynamic centre of this new stage of capitalism – countries have increased the extent to which they have opened their economies externally and deregulated their markets, reducing state participation in the economy in pursuit of the ideal of a ‘minimal state’ – despite the unsatisfied basic needs of a huge portion of the population. Neoliberal policies have been implemented in many countries. These policies seek to dismantle both the welfare state in Europe and the few advances that have been made in Latin America towards enshrining democracy and the rule of law in the constitution and are presented as necessary conditions for economic development and overcoming ‘underdevelopment’.

Public Intellectuals like Dadabhai Naoroji and Sayyid Jamaluddin al-Afghani had rejected the Western imperialism regime of expropriation. They criticised how parts of the global South were being transformed – and ruined – by Western imperialism.

Consolidated to the imperialism premise is the super-exploitation of labour as developed by a group of economists – professors Ruy Mauro Marini, Theotônio dos Santos, Vânia Bambirra, Luiz Fernando Victor, Teodoro Lamounier, Albertino Rodriguez, and Perseu Abramo using and applying Marxist methodology. They define super-exploitation of labour as to the intensified exploitation of the workforce, resulting in an extraction of surplus value that exceeds the limits historically established in core countries. This becomes a fundamental feature of the capitalist system in underdeveloped economies, since foreign capital and local ruling classes benefit from workers’ low wages and precarious working conditions as well as the absence of labour rights, thus maximising their profits and capital accumulation to the intensified exploitation of the workforce, resulting in an extraction of surplus value that exceeds the limits historically established in core countries. This becomes a fundamental feature of the capitalist system in underdeveloped economies, since foreign capital and local ruling classes benefit from workers’ low wages and precarious working conditions as well as the absence of labour rights, thus maximising their profits and capital accumulation

From this perspective of the combined and unequal development of capitalist accumulation in its globalised totality, one begins to understand that the phenomenon of underdevelopment grips the dependent economy. Thus, a relationship of dependence is created and fed by the development of capitalist industry, which transforms some countries supplying raw materials into receptacles of wealth that drain into the industrialised core. The super-exploitation of the workforce is necessary for this drainage to be sustained, which exposes the real process of the production and reproduction of capital in Latin American countries during an era of neo-imperialism.

TOTAL PRODUCTIVITY FACTORS

There are a variety of policies — from improving labour and capital allocation across firms to tackling labour shortages caused by aging populations in major economies —could collectively rekindle medium-term growth.

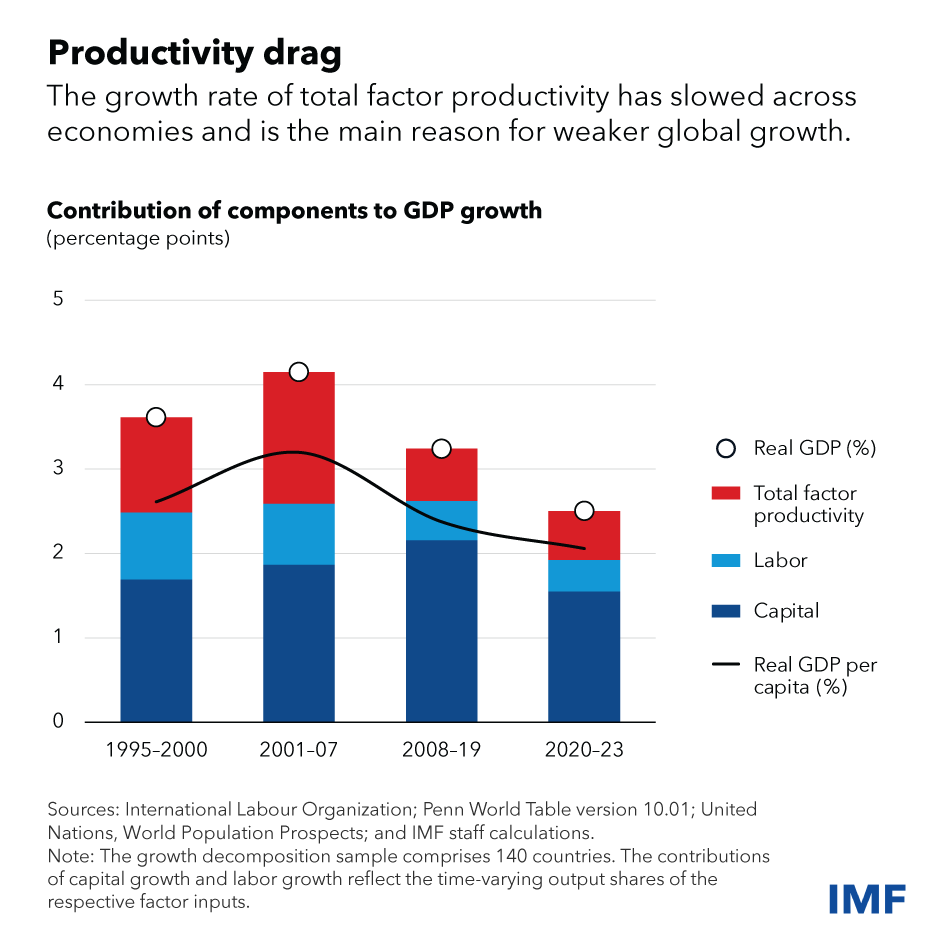

The key drivers of such capitalism economic growth parameter include labour, capital, and how efficiently these two resources are used, a concept known as the total factor productivity (TFP). Between these three factors, more than half of the growth decline since the crisis was driven by a deceleration in TFP growth. TFP increases with technological advances and improved resource allocation, allowing labour and capital to move toward more productive firms.

Then, resource allocation is also another critical element in capital growth factor. Yet, in recent years, increasingly inefficient distribution of resources across firms has dragged down TFP and, with it, global growth.

It is understood that much of this rising misallocation stems from persistent barriers, such as policies that favour or penalize some firms irrespective of their productivity, that prevent capital and labour from reaching the most productive companies. This limits their growth potential. It is stated by IMF if resource misallocation has had not worsened, TFP growth could have been 50 percent higher and the deceleration in growth would have been less severe.

With due concern, there are two other factors that have also slowed growth. Demographic pressures in major economies, where the proportion of working-age population is shrinking, have weighed on labour growth. Meanwhile, weakening business investment has stunted capital formation, and its accompanying capital accumulation impulse.

CoG asserts that it is not population pressure per se in the emerging economies but the exploitation of labour thereon that creates the dependency development patterns which encourages capital to skew towards preferred industry – and firms – in maximal capital accumulation in allegiance to local compradore capital as part of the rentier capitalism scene, (STORM 2021, inequality and ethnocratic hegemony).

In a country case like Malaysia where advocacy of IT promotion by the World Bank is being monopoly-financed by Global North information technology platforms by deepening infrastructural platforms stronghold ,(STORM April 2023) where even the maintenance of fibre optics conduits and routers is dominated by monopoly capital (STORM January 2023, marine cabotage under netarchical capitalism).

The country’s Industry 4.0 initiative is typically maintained by ethnocapital-ethnocratic-clientel-capitalism that neglects the small manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) in the overall industrialisation processes, (STORM June 2023). There is much to discourage this mode of industrial policy arrangement where digital labour is short-circuited, (STORM, March 2023).

Thus, dependent capitalism is defined, first, by the transfer of value from the periphery to the core as a structural dynamic; second, by the super-exploitation of labour as compensatory for the local bourgeoisie; and, third, by a particular type of reproduction of capital in which production and consumption are separated; an expanded elaboration in STORM 2023, foreign capital and social struggles.

ON MID-TERM SITUATIONS

According to United Nations projections, it is accepted that demographic pressures are set to increase in most of the major economies thereby causing an imbalance in world labour supply and therefore moderating global growth. The working-age population will increase in low-income and some emerging economies, whereas China and most advanced economies (excluding the United States) will face a labour squeeze. By 2030, it is expected that the growth rate of the global laboir supply to slide to just 0.3 percent — a fraction of its pre-pandemic average.

Some resource misallocation may correct itself over time, as labour and capital gravitate toward more productive firms. This will go some way toward mitigating the TFP slowdown even as structural and policy barriers may continue to slow the process. Technological innovation may also lessen the slowdown.

As situations stand, it is forseen that overall the pace of TFP growth is likely to continue to decline, driven by challenges such as the increasing difficulty of coming up with technological breakthroughs, stagnation in educational attainment, and a slower process by which less developed economies can catch up with their more developed peers.

It is expected that absent of more major technological advances or structural reforms, the global economic growth can only achieve 2.8 percent by 2030, well below the historical average of 3.8 percent.

OF IMMEDIATE CONCERNS

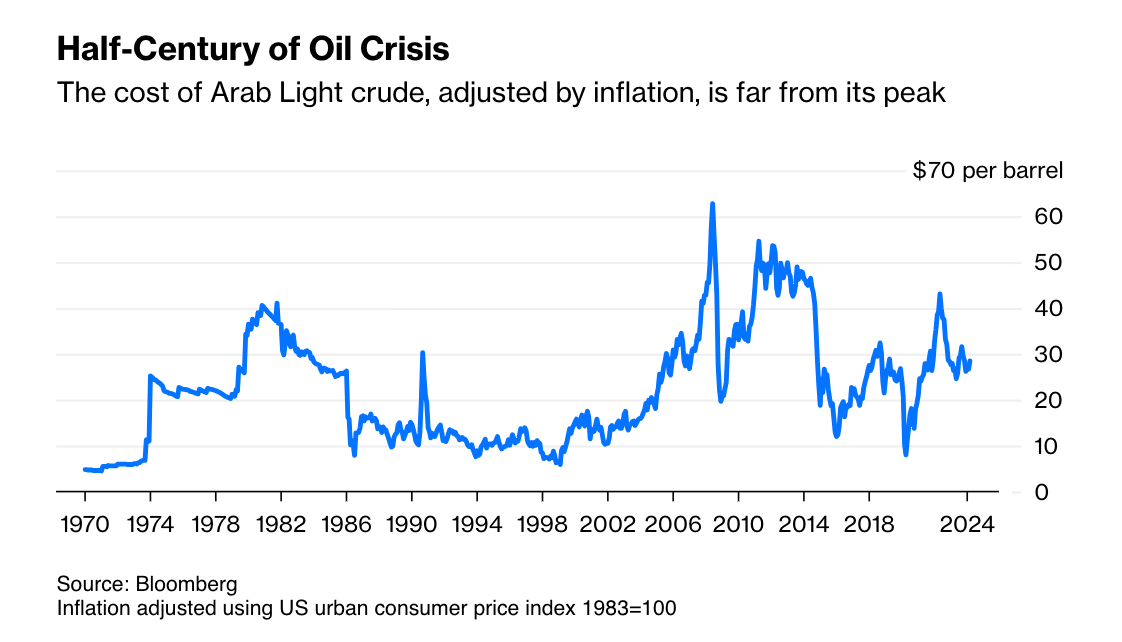

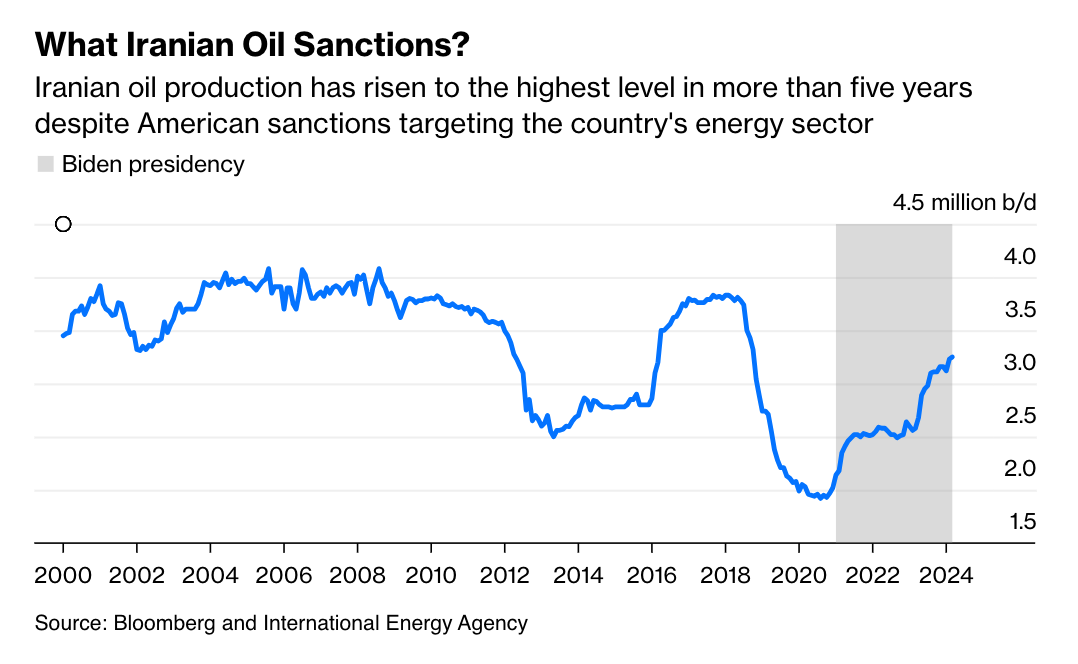

Here are some concerning issues – pertaining to the oil and gas industry – with the threatening MENA geopolotical crisis that affect global economy under the strand of calamity in capitalism, as extracted from Professor Adam Tooze’s Chartbook #275:

- Oil is still flowing. Straits of Hormuz supply 18 million b/d of oil flows through the Persian Gulf – c. 18% of global demand. Unlike the Red Sea, there are no alternative routes. If this is at risk in any serious way, the impact on oil markets will be dramatically chaotic.

- Risk of major disruption has clearly increased, but this likely be reflected in options market most directly.

- China’s demand growth is widely expected to slow this year after an exceptionally strong 2023 as post-Covid travel subsides and its economy slows, but Chinese petrochemicals demand remains robust, though both India and the Middle East will support such demand.

- OPEC+ has been keeping supply tight, but since April there have been signs that they are likely to agree to increase supply at a June 1 meeting. It may choose to keep market guessing by calling monthly meetings and slowly increasing the price of oil.

- There is still plenty of spare capacity with Saudi, Emirates and Iraq keeping 5 m barrels per day off global market = 5% of world demand and more than what Iran is producing. It is assured that only an actual military interruption to Gulf flow shall in some ways to threaten a serious shortage.

6. Then, there is the US (SPR) Strategic Petroleum Reserve (half its former level) but still enough to move the market.

As the Dallas Fed analysis shows, measured relative to the IEA standard of net imports, the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve is more than adequate to support its capitalist economy because the US is now a major net exporter of oil.

GLOBAL GROWTH REVIVAL

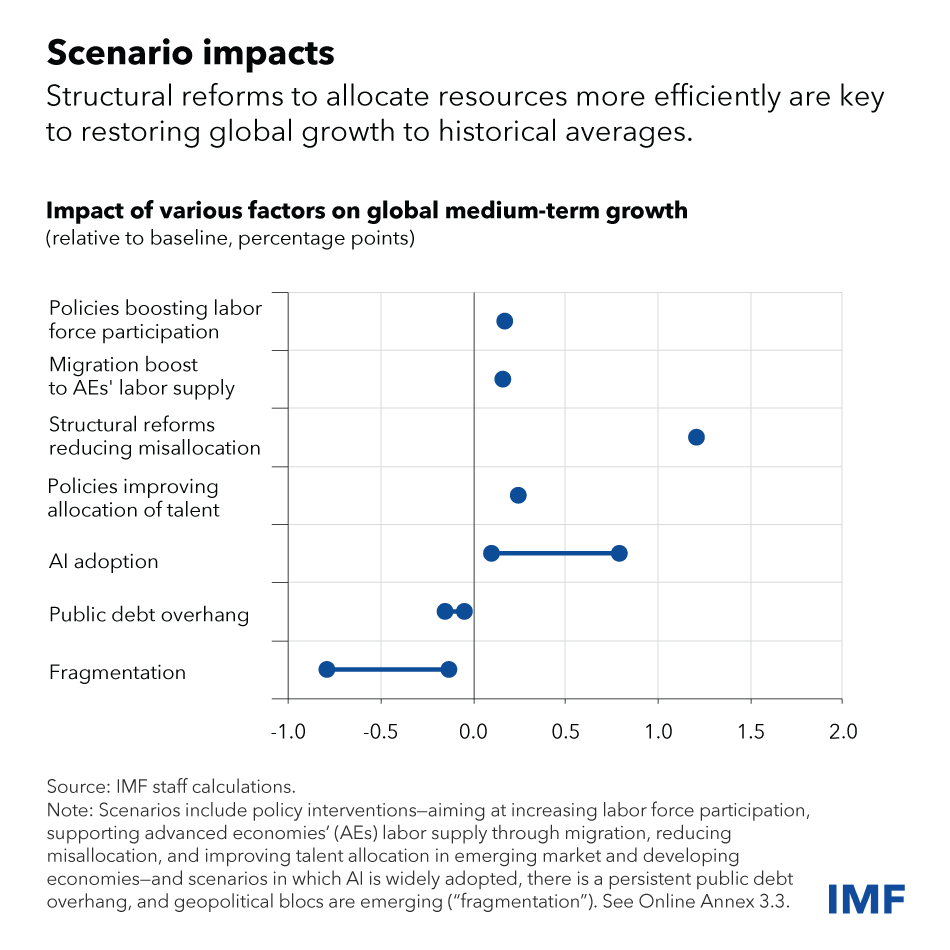

The IMF analysis further evaluates the impact of policies on labour supply and resource allocation, set against the backdrop of the rapid advance of artificial intelligence, public debt overhang, and geoeconomic fragmentation, (exemplified by country case studies in STORM January 2024, STORM April 2024, STORM June 2023, respectively).

Through examining scenarios featuring ambitious, but achievable, policy shifts that address resource misallocation – it is by improving the flexibility of product and labour markets, trade openness, and financial development. The IMF team also consider policies aimed at enhancing labour supply or productivity by reforming retirement and unemployment benefits, supporting childcare, expanding re-training and re-skilling programs, and improving integration of migrant workers, as well as the removal of social and gender barriers.

Their findings indicate that the benefits of increasing labour force participation, integrating more migrant workers into advanced economies, and optimizing talent allocation in emerging markets are comparatively modest.

By contrast, reforms that enhance productivity and fully leverage AI are key for reviving growth in the medium term. The analysed findings suggest that focused policy actions to enhance market competition, trade openness, financial access, and labor market flexibility could lift global growth by about 1.2 percentage points by 2030. The potential of AI to boost labor productivity is uncertain but potentially substantial as well, possibly adding up to 0.8 percentage points to global growth, depending on its adoption and impact on the workforce.

In the long run, innovation-driven policies will be crucial to sustaining global growth.

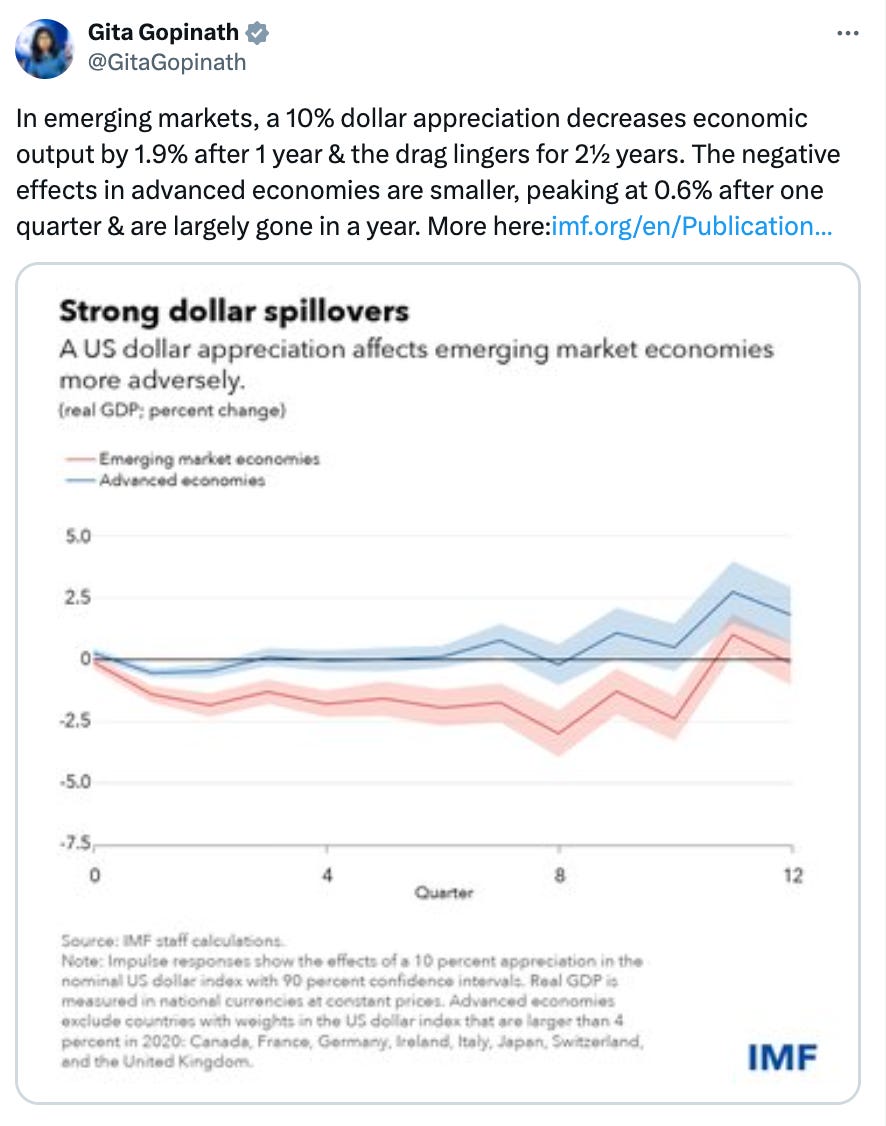

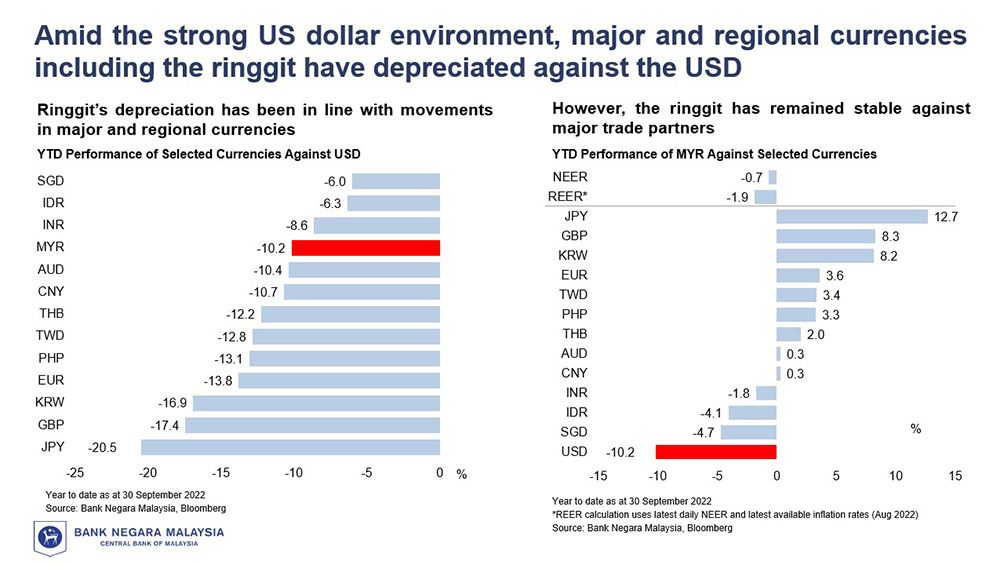

CoG is of the opinions that innovative policies may not be able to sustain developing economies because the appreciation of the US dollar has immense impact upon these affected countries, that is, a strong dollar is bad for the global economy.

The currencies of G20 countries are almost all depreciating against the dollar. The decline since the beginning of the year has reached 8% for the yen and 5.5% for the South Korean won, led by the Turkish lira at 8.8%. Both developed and emerging economies have seen currencies weaken at an accelerating pace, with the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, and euro falling 4.4%, 3.3%, and 2.8%, respectively, in developed economies.

Governments are increasingly concerned about the falling value of their currencies. Emerging economies are particularly sensitive to the negative effect, as the burden of dollar-denominated debt increases along with larger interest expenses due to higher rates.

Several countries have already begun to take actions. On April 1, Brazil’s central bank intervened in the foreign exchange market for the first time since President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva took office. Although the government and the central bank have not clearly explained their intentions, some in the market believe that the purpose is to correct the depreciation of the real.

Several local media outlets report that Bank Indonesia also decided to intervene in the currency market this month. The objective is to correct the level of the rupiah, which is at a four-year low. But the rupiah has been on a downward trend since those reports, falling beyond the milestone level of 16,000 rupiah to the dollar. According to Reuters, Bank Indonesia Gov. Perry Warjiyo made a statement at the end of January that was intended to check the currency’s depreciation. The central bank has taken steps to intervene, but they have not been fully effective. Indeed, by mid-April 2024, the rupiah tumbled to its weakest

in four years as the market reopened after the Eid al-Fitr holidays, prompting the

central bank to intervene in the market to stem its slide.

The rupiah has declined as much as 2.27% to 16,200 per US dollar, its weakest level since early April 2020, leading the losses among emerging Asia currencies, (theedge ceo briefing, 17/4/24).

Turkey’s central bank raised its policy rate by 5% to 50% in March in response to the lira’s depreciation and accelerating inflation. … “We are feeling a bit more hawkish than before,” Eli Remolona, the Philippine central bank governor, said recently, citing the higher risk of inflation.

These concerns are not just limited to developing economies, Japan and other developed countries are nervous about the incessant depreciation of their currencies.

While the Malaysian prime minister talks about “de-dollarization”, the Ringgit would hit RM5 before such measure could see any meaningful results. Those who argued that a weak currency is good for exporters have forgotten that it equally impacts imports – hence the cost of living had skyrocketed. To add salt to the wound, exporters and corporations are holding foreign reserves in dollar, refusing to convert it back to Ringgit, ( see STORM, March 2024, on depreciating ringgit).

This essay is based on Chapter 3 of the World Economic Outlook, “Slowdown in Global Medium-Term Growth: What Will it Take to Turn the Tide?”, reflecting the research by Chiara Maggi, Cedric Okou, Alexandre B. Sollaci, and Robert Zymek; supplemented with additional datasets and extra information contents by the Collective of Geoeconomics team.

You must be logged in to post a comment.