Over the past 30 years, only 33 countries have made the transition to high-income status

That economic growth since independence gained a generation ago has not benefited all rakyat2 equitably, including slower income growth especially among younger and lower-skilled workers, inequitable access to quality education, and inadequate social safety nets for the poor is a testimony that neoliberal economic development under capitalism does not benefit anyone but a class of ethnocapital colluding with compradore corporate capital in taking on a new phase in the globalization of production and finance with monopoly-capital collaboration.

Whereas an ethnocratic governance is representatives of an ethnic group that is holding a disproportionately large number of public posts to advance their ethnic group to the disfranchisement of others, the ethnocapital in this country is specifically the Malay-dominated kleptocrates who had lorded over the country since 1957.

What had these ruling regimes shown are RACE, RELIGION, ROYALTY, and POLITICS but not equality in the distribution of wealth.

1] WEALTH INEQUALITY

Succeeding oligarchy regimes had continued maintaining a clientel ethnocapitalism domitnation over the working class rakyat2 with 1% of the bumiputera population (see Khalid lse.blog) or about 40,000 ethnocapital political families running and looting – and ruining – the national economy. The undeniable fact as to why many bumiputera had not attained parity despite +60 years of neo-liberal-enforced economic development is the existence of a new class of compradore capitalist. With post-industrialidation and the introduction of financialization capitalism, the role of clientelship capitalism had inserted into the monopoly-capital supply chain in an age of imperialism. Corporate capital in the SMEs collaborates with Global North to tighten the commodity supply chain with monopoly-capital M&E vendors like AIDA, SKF, Cohu, VAT, Oerlikon Balzers, Favelle Favco, Bromma, Vitrox, etc.; recently, Digi, Nestles and British American Tobacco are, by market capitalisation, leading the list of foreign companies that dominate Malaysian businesses in alliance with Global North monopoly-capital – all in furtherance of neo-imperialism penetration that by now the country is an ownership of a failed state, (see Aliran 2021).

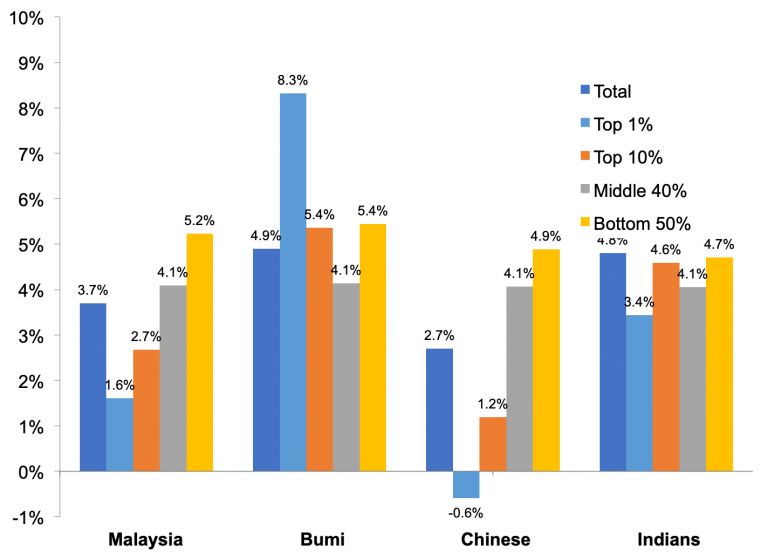

That capitalism fails as a good society is evident from a simple examination of its main features. Capitalism is not towards human development but privately accumulated profits by a tiny minority of the population. The implication is that although the middle 40 per cent and the bottom 50 per cent benefited significantly from economic growth, more glaringly is the ethnocapital Bumiputera in the top income groups (the top 1 per cent and the 10 per cent) benefitted the most from economic growth :

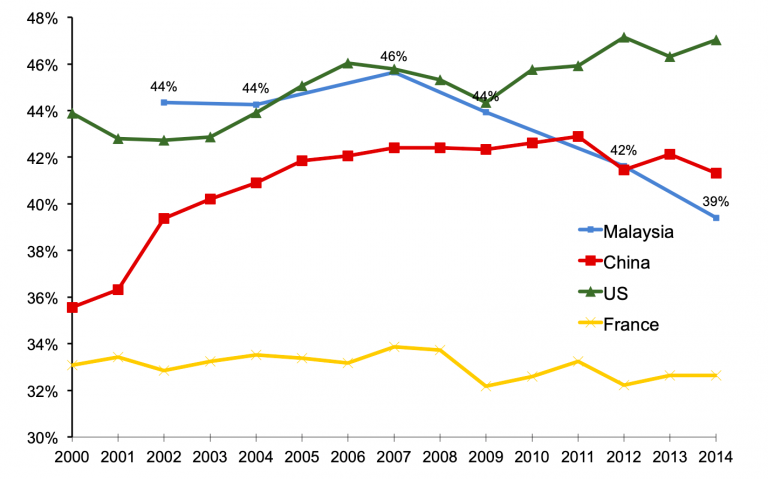

Indeed, even thirty years after the NEP (New Economic Policy) implementation, by 2002, Malaysia’s inequality level was then still remained extremely high: its top 1 per cent income share was 19 per cent and the corresponding number for the top 10 per cent was 44 per cent, which is higher than those of the US and substantially even higher by inequality than those of China until post-2012 :

It is during this period where the share of the wealth is acutely benefitting the high-income group of capital-endowed class :

As the household income has since raised Malaysia’s average poverty line income (PLI) to RM2,208 from RM980 in 2016, this means that the new metric brings Malaysia’s absolute poverty rate to 5.6% in 2019. This means that almost 6 out of 100 households in Malaysia could not afford to meet basic needs like food, shelter and clothing.

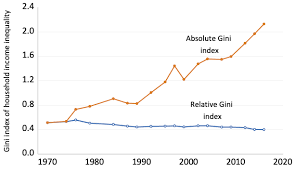

In 2019, the high-income T20 household would have earned 10 times more than the low-income household. In 2020, the high-income household still earns 6.7 times the low-income household. Though the Gini coefficient relative gap has narrowed, the absolute Gini coefficient gap has increased (as an instance, the earnings difference of T20 was RM$9,000 in 2019, but it was at a very high figure of RM$17,000 by 2020). Therefore; there is no equality improvement, but extremely widen inequality cutting across racial groupings :

3] INEQUITABLE ACCESS TO QUALITY EDUCATION

Students in public higher education institutions in Malaysia 2012-2019, by gender are that in 2019, around 291.53 thousand male students and 415.02 thousand female students were enrolled in public higher institutions. The country had 20 public universities, 53 private universities and six foreign university branch campuses; and 403 active private colleges of various categories.

Yet the graduates unemployment rate is high despite all the education’s public and private infrastructure and corporate capitalism investment.

The primary and secondary school enrollment was reported at 43 % in 2019, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators, compiled from officially recognized sources. This is well below even the middle-income developing states.

Malaysia spends a large share of the national budget on education, yet learning outcomes have consistently fallen below expectations according to a recent World Bank Report which is often well articulated at various times by many rakyat2 like the question of

Is there Anything Wrong With Our Malaysian Schools? by Teck Zhee Liew

i) Not surprisingly, literacy rates are high in Peninsular Malaysia, at 95%, but it has to be noted significantly lower in Sabah and Sarawak, at 79% and 72% respectively, because their communities are poor, inaccessible, less educated and probably have lower expectations of their children. Irresponsible teachers take advantage of this by reporting for work but not attending classes, and falsifying records.

“Imagine a student walking an hour and a half to school, where there is no path or public transport, only to find no teacher when he arrives. Who is to blame? What can parents do if they are not literate and cannot afford to find out whether the teacher had to attend to regular, non-classroom administrative duties or was simply negligent, backed by a local politician who helped appoint the teacher in the first place?” Unesco Global Economic Monitoring Report 2017/2018 (GEM)

ii) The unfairness and inequality perpetuated by succeeding ethnocapital ruling regimes had only reinforced a phenomenon where the good – and well-to-do – students have exercised the exit policy and opted for the private sector where it is more lucratively beneficial to corporate capital. We are witnessing capitalism intensity with corporate capital investing in what were once regarded belonging to the public sectors ( whether it is in the pharmaceutical industry or the telecommunications sector ), and the resultant outcome is the mushrooming of international and private schools and tuition centres, and home-schooling becoming an alternative and popular learning choice to public educational institutions; we are having more private (corporate capital funded) universities than public institutions.

“If the situation worsens, there will be little left of national schools.”

iii) Politically, teachers are a sizeable vote bank, and politicians are quick to defend them no matter the situation, but we know that bad teachers are the weak link in the education system. We have heard this many times before: we may have picture-perfect policies but implementation is imperfect.

Datin Noor Azimah Abdul Rahim, chairman of Parent Action Group for Education Malaysia (PAGE) had expressed that according to the recently released Unesco Global Economic Monitoring Report 2017/2018 (GEM), “a review of teachers, school administrators, parents and officials in 24 countries found that 54% believed the code of ethics had a significant impact on reducing misconduct. Therefore, the teacher code of ethics shall be the guiding light“; but, unfortunately – and inevitably – oligarchy regimes are more interested in illicit capital and illegal tradings than management on the economic imperatives and rakyat2 welfare.

4] INADEQUATE SOCIAL SAFETY NETS

At about 0.7% of gross development product (GDP), Malaysia’s spending on social safety nets is much lower than almost all countries that have graduated to high-income status since 2000, which generally spend about 1.5–3.4% of GDP.

According to Ken Simler, Senior Economist, Poverty and Equity of World Bank Group, Shakira Teh Sharifudin, Senior Economist, Macroeconomics, Trade and Investments, World Bank Group and Zainab Ali, Research Analyst (Poverty and Equity) at World Bank Group: in the Aiming High: Navigating the Next Stage of Malaysia’s Development report, the national’s large commitments to operating expenditures such as salaries, pensions, and debt service payments have put continuous constrains on its ability to allocate more for social spending, as well as projected spending on long-term economic development.

The country, nearly everyone at the bottom 20% (B20) income group receives some form of social assistance, but they enjoy only 29.5% of the total program benefits. In contrast, a large share of social transfers ends up in the M40 (37.2%) and the T20 (9.5%) households.

Indeed, since 2012, Malaysia’s revenue collection as a percentage of GDP has been on a persistent decline, and this has negated a national’s ability to provide the high-quality public services and social safety nets that the expanding middle-class increasingly expects.

In 2019, Malaysia’s revenue collection stood at 17.4% of GDP. The country’s operational expenditure constitutes 80% of budget allocation is definite exceedingly far below her investments expenditure. As a dire consequence, the revenue collection is regarded as well below the average figure for upper-middle-income countries (28%) and high-income countries (36%). The nation severely under-collects in key revenue areas such as personal income and consumption taxes, in part from an expansive system of tax deductions and exemptions across all income levels rather than selectively be towards the T20 class.

Not only that, with the exception of the real property gains tax, the nation has minimal tax capital gains and there is no wealth tax in place: thus, reinforcing our argument that the corporate capital stronghold within a clientel capitalism environment is where the ruling class set to enjoy its wealth substantially, and indefinitely.

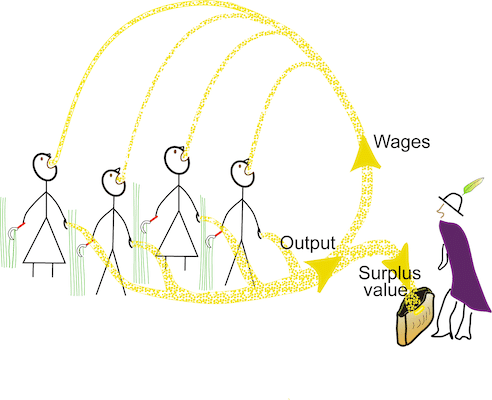

Then again, responding to the World Bank 2020 World Values Survey on whether it is an “essential characteristic of a democracy that governments tax the rich and subsidize the poor”, unlike in many other countries, most Malaysians had an indifferent view. It seems that the strife towards class discrimination has yet to attach traction. Without strong political intervention, and a teach-in initiative to be followed by appropriate and adequate processes in dismantling the kleptocrates’ capital superstructure, the clientel class of bourgeoisie leeches shall remain to suck rakyat2 labouring effort dried through surplus value expropriation.:

5] THE CLIENTEL CLASS

The twenty-first century rentiers are everywhere, scooping returns accruing from natural resources, investments, from land, from housing, monopolistic utilities, consumer credit, long-term contracts and infrastructural platforms’ data. The core feature of rentier capitalism is the resurgent capitalistic power that spans cultivated resources, fossil fuels, mined resources, finance, housing and the public sector out-sourcing rackets which generated surplus values that are being expropriated.

Rentier capitalism needs also be understood as part of political clientelism where over time, “citizens came to expect and rely on patron-client relationships, nested within party machines, albeit reinforced by carefully structured distributive and development policies”, (Meredith L. Weiss, The Roots of Resilience: Party Machines and Grassroots Politics in Southeast Asia, Cornell University Press and the National University of Singapore Press, 2020, p.76), where clientelism is the feature of Malaysian politics, fostered forcefully by the BN and UMNO ruling elites, whence even opposition parties had began to replicate that behaviour, too.

By delving into a class analysis of clientel capitalism, we shall discover that the power or dominance relations among persons, their subsumed class to entitled positions is where political power defines economic dominance and social status deference.

We shall define the concept of class “places” as distinguished from class positions where “places” exist at each of the these levels of society: economic, political, and ideological (or cultural) levels where at the latter, social dominance regards bumiputeras status and on an islamic allegiance, for instance.

By ethnocapital we mean a (malay) bumiputra owned and controlled an entity performing under a rentier or clientel capitalism approach whether it is a public agency, a government-linked company (GLC) or a privatised and or commercial enterprise.

Between the dominating and the dominated, under capitalism the bourgeois are really

dominant at each level whereas the proletariats dominated at each.

The clientel capital [place] had aligned with economic oligarchs [positions] in accepting rentier capitalism to sustain their hold on [power]. They adopt this clientelism as solicitations for votes at the grassroots level, allowing ruling elites [place] the party patronage [position] and political [power] to “effectively partisanizing them and ensuring ground-level officials with whom most voters interacted with ……are political party loyalists” (Weiss, 2020), resulting in the skewed distribution of profits by political stakeholders and the stark inequality of wealth permeating in the country as clearly expounded in a LSE.blog by Khalid.

The outcome of rentier capitalism is swelling of economic inequality and deeper socio-economic injustice in the country thus widening the class struggle within.

Specific corporate components exploration on Rentier Capitalism in Accumulation HERE

The Political Economy of Malaysia – a brief survey on the development of underdevelopment, economic stagnation and socio-economic inequality under Neo-Imperialism regime with neoliberal policies – is presented HERE.

You must be logged in to post a comment.