10th March 2023

1] INTRODUCTION

Since the inception of the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) in 1996, succeeding regimes in governance have been persistently promoting the digital agenda through multiple initiatives such as the National Strategic ICT Roadmap and Digital Malaysia (2008-2012), National eCommerce Strategic Roadmap (2017), Industry4WRD (2018) and the latest National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan (2019-2023).

The nation has a total workforce of 15.1 million. More than a quarter of this — 26% or a huge 3.9 million people to be exact — are participating in the gig economy: such as ride-hailing, e-commerce delivery, and computer programming.

The country’s digital economy is even estimated to be worth over RM$ 270 billion, which equates to nearly 18% of Malaysia’s gross domestic product, (YCP Solidiance, 2020).

Wow! At their peaks, SIA constituted only 4% of the Singapore economy, and Walmart dominated 10% of Mexico economy.

2] WORLD BANK DIGITALISATION FRONTIERS

On the Malaysia Economic Monitor, February 2023, the World Bank is rather persistence in advocating the advancement towards a digital economy. Though while advocating Big IT development as a means of continuing capital employment, and consequential deployment of monopoly-capital to own and control infrastructural platforms, this organised entity of US imperialism is only encouraging capital accumulation with extracted value from states – to ensure Global North Big Tech infrastructural platforms shall continue benefiting on expansive exploitation, through global labour arbitrage where underemployed labour is truly exploitated, (read STORM, 2022, Big Tech Large Gig), and STORM 2023, Big Tech in Marine Cabotage where such transnational (TNCs) infrastructural platforms would even dare to hold our nation in a technical ransom on undersea communication cabling installation and maintenance.

Indeed, the large RM$1.5 billion IT allocation in the Revised Budget 2023 will benefit only wealthy and the well-connected companies – not our local SMEs entrepreneurs – with their huge expenditure for consultancy services, and perpetuating other cock-ups, (Hunter, March 2023).

A digital economy shall signal how infrastructural platforms are not only incrementally becoming invasive as techno-feudalism in the country, but once franchised by privatisation and outsourced to the Global North monopoly-capital that even local compradore capital shall collaborate to accumulate their capital by and functioning as intermediaries.

Take the National 5G case. Vested interests are calling the withdrawal from Swedish telecommunications giant Ericsson in the 5G network, (theedgemarkets, 10/3/23). The Financial Times on 6th March, 2023 reported that Huawei is lobbying for a role in country’s 5G roll-out. Then, Telekom Malaysia (TM), is also competing in this industry, too, and it is not considered a neutral entity in rolling out the network, but a national telecommunications monopoly.

Related Readings: Financialisation Capitalism; Digital Feudal Lords

3] THE DIGITAL ECONOMY

It is not just having multiple programs like eLadang, Pemangkin to Satellite Farms immersing in the metaverse world, any Digital Economy demands an assurance on buy-in from employees to lower resistance to change, and upskilling or reskilling existing talent within various companies through trainings, too.

And these constraints are not adequately nor appropriately attended, especially when the SMEs

are not well-funded nor properly supported by government agencies, as yet:

Compounding the productivity element, labour quality contributed only about 8% to real GDP growth over 2001-18, much lower than the OECD average.

Read also : Digitalisation, Capitalism and SMEs.

Combined comparatively with inadequate IT systems deployment and infrastructural projects implementation, there is still a long drive on our digital highway to cruise forth, and by.

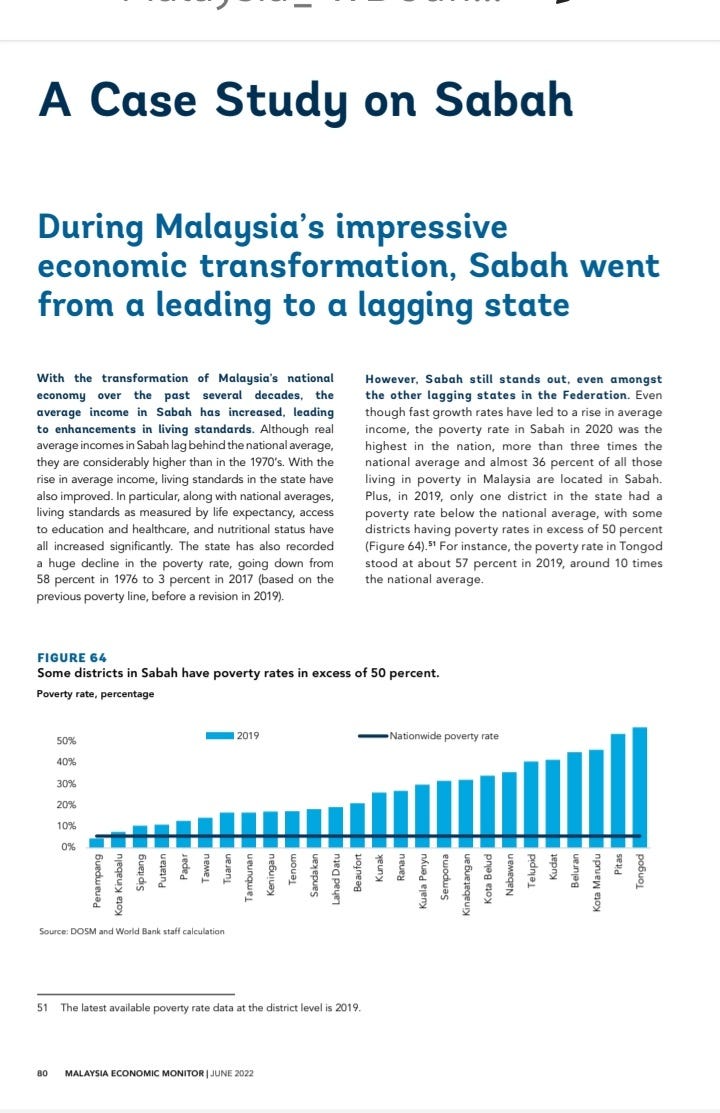

Indeed, the World Bank Report, June 2022 stated the inadequacies of IT implementation in the Sabah state of Borneo (read also csloh: Sabah – a state underdeveloped) is due to lagging in economic transformation:

Amplifying another factor is that our high-speed broadband accessibility is considerably more expensive compared to other countries, (read STORM, Digital Knights).

According to a study on internet access affordability in 2021, people in Malaysia had to pay 26.58 U.S. dollars per month on average for broadband internet access. Meanwhile, the cost of mobile data per 1GB was at 0.45 U.S. dollars per month, (data as released by Statista Research Department, 28/9/22).

Further, Malaysia ranked 74 out of 167 countries in terms of price per Mbps for fixed broadband services, and 64 out of 118 for fiber broadband services – way behind regional peers such as Singapore and even Vietnam.

Enmeshed within these Real Geoeconomics are the socio-economic factors of poverty and inequality that exist in a stark manner in the states of Perlis, Kelantan, Trengganu and Sabah

where there are high unemployment rates among the youth and the emergence and expansion of youth that can be termed as “the precariat” [Guy Standing’s definition (2011)] as the mass class characterized by unstable labour, low and unpredictable incomes, and loss of citizenship rights.

First used by French sociologists in the 1980s, the precariat describes persons “working precariously, usually in series of short-term jobs, without recourse to stable

occupational identities or careers, stable social protection or protective regulations relevant to

them”.

Then, there is the emergence of a “cybertariat” type of worker has created an awareness about the multilateral ways by which mutually reinforcing economic, political and technological factors are transforming not only the global economies, nature and application of work, but also each individual lives, (Ursula Huws, Labor in the Global Economy, 2014 and The Making of a Cybertariat: Virtual Work in a Real World, 2003).

Thus, this informal employment sector occupies a sizeable segment of the country’s workforce that inevitably is without adequate social security safety provisions in place, (read csloh, 2022: Workers; Emir Research: Brain Drain; bernama: gig-economy and Khazanah Research Institute 2020, Shrinking “Salariat” and Growing “Precariat”?):

4] DE-INDUSTRIALISATION AND DIGITALISATION

The present renewal objective in advocating the digital economy is no more than a bad decision in the premature de-industrialisation process during the 1990s.

In Malaysia case, though, the years since 1970, the lack of significant technological upgrading, and the required structural change as a follow-up, has caused the premature plateauing of manufacturing, stemming from failures to coordinate policies, enforce standards, sustain high productivity growth and stimulate transition to higher value-added activities.

The resultant outcomes are that in the Global Value Chains, the country’s attractiveness as an outsourcing base has weakened. Further, rhe contribution of foreign value-added in the manufacturing sector’s export growth has also declined. There is micro-level evidence pointing to weaknesses in terms of human capital and technology, too.

Compounding these situations, there was the often ‘stalling’ – temporarily or complete closure – of the many Malaysian industrial projects that weakened workers employment,

(Jeffrey Henderson et al., Capitalism and Industrialization in Malaysia in Economy and Society, Volume 36, 2007 – Issue 1). Manufacturing as a whole has began to register a slower wage growth since the late 1990s, with labour markets characterized by heavy presence of low-skilled foreign workers, increased contract labour and/or outsourcing and the subsequent declining worker organization. The focus on sweat-based low-skilled foreign labour rather than on expanding professional and skilled labour locally has driven Malaysia down the low industrialization road as a result, (see Rajah Rasiah, Vicki Crinis & Hwok-Aun Lee in Industrialization and Labour in Malaysia).

In fact, a number of Malaysian firms have even relocated their research facilities and/or manufacturing plants to Cambodia and Vietnam to access more developed and expanding markets according to Rasiah, whereas the poverty of Malaysian industrial workers has persisted, and the precarious labour has continued, exacerbated by the dependency on migrant labour that had inadveribly reduced national labour surplus value tremendously.

Then, the concurrent continual enforcement of colonial industrial legislations (see, STORM 2021, Union Busting) had suppressed any broad or even marginal salary gain through the decades.

in the case of Loh Guet Ching v Myteksi Sdn Bhd (berniaga atas nama Grab) e-drivers are considered “independent contractors” and do not have the right to be heard before the Industrial Court for the alleged unfair dismissal by Grab. In short, with digitisation of an economy, the gig-labour is considered a sui generis class with different legal rights and obligations from 9-to-5 employees as a new dimension to the labour force without adequate social security nor workers rights as an employee of a corporate entity.

Whilst, corporate Malaysia has much to gain with merchandise sales through an e-commerce economy:

5] CONCLUSION

Labour, hence, becomes digital-dehumanised workers where they are mere inputs in an interfacing intermediaries loop as conduits to big data storage and retrieval. A gig-worker daily experience and personal assets are exposed to financialisation or value extraction.

The consequential manipulation of such raw data into timely, accurate, relevant and complete information – by infrastructural capitalism platforms that are so overwhelmingly powerful in exploiting not only surplus value of labour but in the regal accumulation of capital relentlessly, too, (Social Europe, Gig Workers Guinea Pigs of the New World of Work, February, 2021, and to see Foundation for European Progressive Studies, Governing Online Gatekeepers: Taking Power Seriously, 2021).

In short, where the underemployed youthful and useful gig-labour is exploited to the finite digit.

You must be logged in to post a comment.