12/02/24

I] THE BEGINNING

By financialization capitalism one means an emerging form of capitalism that increasingly uses finance, and apply financial tools and means, in the operations of capitalism (John Bellamy Foster, The Financialization of Accumulation, Monthly Review vol:62, issue 05 October 2010), or simply as the financialization of the accumulation of capital process (Paul Sweezy, “More (or Less) on Globalization,” Monthly Review 49, no: 4 (September 1997).

The defining process of accumulation in financial capital would involve the investment of money or any financial asset to increase the initial monetary value of any said asset in anticipation of a financial return whether in the form of profit, rent, interest, royalties or capital gains.

This shift in economic activity from production, and in the service sector, to financial activities that generate high private rewards disproportionate to their social productivity – according to James Tobin, Nobel Prize in Economics 1981 – is one central aspect whereby the surplus value, that is, the added value created by workers in excess of their own labour-cost is being appropriated by the new financial capitalists as profits, (Marx, The Capital, chapter 8). This surplus value as the source of society’s accumulation of fund or investment of fund, part of is re-invested, but part of it appropriated as personal income, and used for consumption purposes by the owners of capital assets themselves. The workers cannot capture this benefit directly because they have no claim whatsoever to the means of financial creation or its final production.

The thrust of imperial penetration into underdeveloped economies resulted in deepened financial dependence, (see Magdoff 1978, Imperialism: From the Colonial Age to the Present and Magdoff, 1969, The Age of Imperialism; also refer to Foster “The New Imperialism of Globalized Monopoly-Finance Capital – An Introduction”, Monthly Review, Vol:67, Issue 03), like presently in Brazil, Venezuela and countries in the sub-Sahara region where the domination of global monopoly-finance capital has attracted portfolio investment, and to pay off their external debts to international capital, including the IMF (where global debt remained at USD 235 trillion) that accrued high interest rates, de-industrialisation of developing nations, slowing growth in emerging economies, and the continuance vulnerability in the rapid movements of global finance (IMF, World Economic Outlook, 2015; IMF squeezing poorer nations; New debt crisis threatening Global South; IMF’ed with Global Debts).

II] THE PROCESS

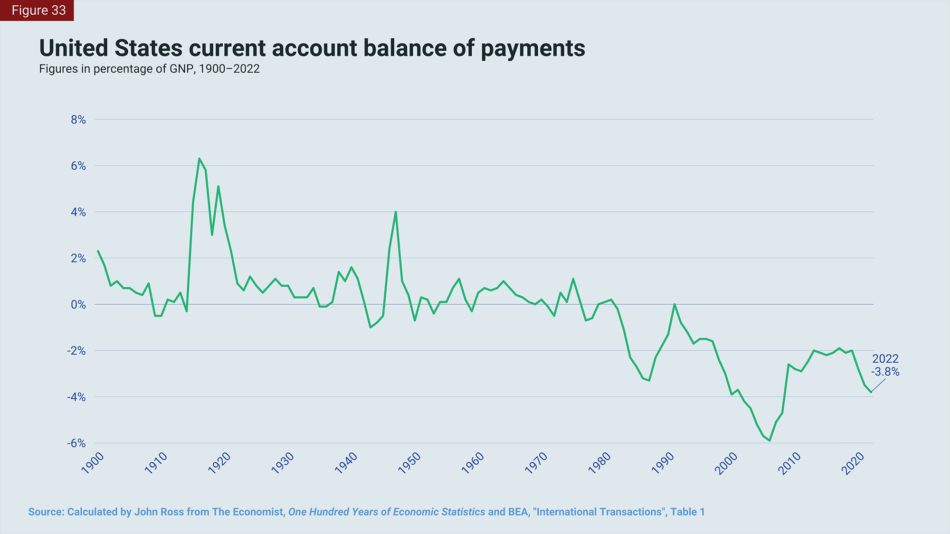

From 1913 to the early 1980s, the US generated more surplus than it invested ‘domestically’. It had a surplus of capital that it could invest in other countries and extend its international hegemony not only through violence. Post-WWII, the particular beneficiaries of this form of neo-colonialism were imperialist countries whom the US wished to enmesh, integrate, and dominate, as exemplarily executed by the Marshall Plan in Europe. Other beneficiaries, such as the Republic of Korea, became military frontier states to constrain Russia and China and thus received predominantly US economic investment.

To prevent effective economic competition from these countries, the United States used political and military pressure to force down their rates of investment and, therefore, growth rates. The decoupling of the US dollar from gold in 1971, and hencefore the removal of restraints on the weaponisation of the US control of the international monetary system, played a key role in this process, (see Hyper-imperialism, 2024).

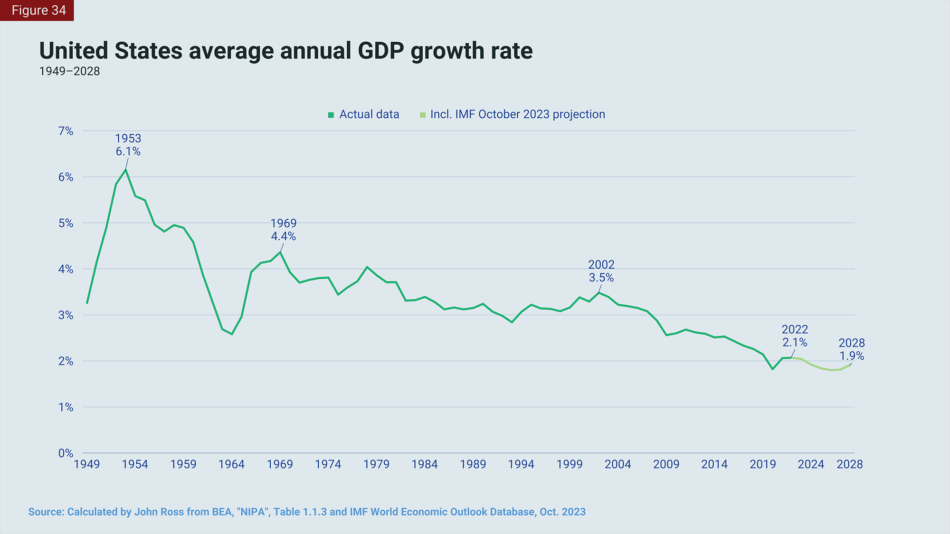

However, despite this ability to slow down her imperialist rivals, the US proved incapable of raising its own economic growth rate (to achieve a new higher rate of investment and exploitation), partly because of the withdrawal of US-based capitalists from long-term productive investments within the United States, (read STORM, 24/08/23, Capital Imperfection and Socialism Efficiency). Indeed, US economic growth decelerated further – the average annual economic growth of the US today is only 2.0%, less than half its growth rate in the 1960s and far behind the rate of growth of China or even compared to some Asian tiger economies. The figure below shows that the US has had a long-term overall decline in average growth rate since 1953, (see STORM Capital Imperfection, ibid).

Confronted with this situation, the US has subsequently turned to tariffs, economic sanctions, and technology bans, leading to an increasingly protectionist environment where sanctions warfare doesn’t work. Despite its economic decline, the US still maintains a military lead over all other states. US Imperialism, therefore, now turns to a growing reliance on her armed force, (US Military Spending, MR November 1st. 2023).

With a multi-prong and multidimensional approach to maintain, and retain, as the sole hegemonic power – within an imperial hubris – the U.S. is attempting through tariffs, financial and technology sanctions, political provocations to – and military maneuvers near – Taiwan and a neo-imperialism policy pivot as an encirclement of China, and the economics in threaten banning of Chinese companies such as Huawei and Tik Tok. Now, more than ever, it is an appropriate time when readers should begin to dissect the imperfections of a capitalist economy when competing with a state-run socialist model like China.

III] RAMIFICATIONS

The creation of monopoly-finance capitals in the neoliberalism economy of Malaysia is no more than the hegemonic economic ideology of the thenThatcher and Reagan regimes reflecting the new imperatives of capital – advancing IT-geared financial globalization planted in Malaysia as the engine of financialization capitalism model (Lena Rethel, Malaysian Capitalism, Rents, and Financialisation, University of Southampton, 2010; read also STORM, 21/04/2023, Financialisation of Capitalism in Malaysia).

In the early 1990s, Malaysia corporations sought funds from the domestic equity market while non-financial enterprises relied on bank debt and the issuance of bonds abroad. Since 2003, however, the corporate bond market has reached an unprecedented size of RM$190 billion, while similarly since 1999 the total private sector bonds outstanding have surpassed that of public sector bonds (Bank Negara, 2007). This expansion of bond finance favours bigger corporations linked to the government (the GLCs) – much to the disadvantage of the Chinese and Indian capitals’ SMEs that do not have the sizeable funding resources.

The ensuing financialization of Malaysian capitalism led to the emergence of a new politics of debts, and it also coincides with rising levels of household indebtedness. In a way, it reconfigures society where share ownership and shareholder value take preeminence, a growing influence from capital market-based financial system, the further entrenchment of the political renter class power as well as the polarization of wealth and income, and the explosion of financial innovation and trading that led an economy more towards “speculation” than the engenderment of production to be equally shared by rakyat (Costa Lapavitsas, “The financialization of capitalism”, SOAS abstract).

The above processes occurred when the existing relationship between the various forms of capital rent-seekers collude. Under the New Economic Policy (NEP) with state capitalism this process only accentuated with increased financialization, reinforcing the existing strand of an ethnically divided capitalism (Searle 1999, Riddle of Malaysian Capitalism, Asian Studies Association of Australia; STORM, June 2021, clientele capitalism collusion). The country’s economic initiative was to be in alliance with the private sector, especially while in collaboration with Chinese capitals during the early 1980s, was also evidently prominent in the collusion of the privatization of state assets at that period, (Heng Pek Koon, The New Economic Policy and the Chinese Community in Peninsular Malaysia, The Developing Economics, 1997; STORM, June 2022, capital accumulation and clientele capitalism).

Whereas the majority of businesses built during the prewar period were found in the tin and rubber industries that comprised illustrious family firms founded and built by Low Yat, Loke Yew, Chong Yoke Choy, H.S, Lee, Tan Chay Yan and Lau Pak Khuan who colluded with imperial British plantation interests to build their empires, the “new money-capital” entities like YTL Corp’s Yeoh Tiong Lay, Berjaya’s Vincent Tan, Genting’s Lim Goh Tong, Sunway’s Jeffrey Cheah, Lion’s William Cheng and the Ananda Krishnan groups and business stables attempted the forging of more Sino-Indo-Malay corporations, that is, a co-opetition strategy whereby Chinese and Indian capitals can compete as well as co-operate with Malay interests, (see Neo Yee Pan “The Role of Chinese Business in the Context of Our National Objective” paper delivered at the MCA Economic Congress, March 3rd. 1974; Jesudason 1989, Ethnicity and the Economy: the State, Chinese Business, and Multinationals in Malaysia, Oxford University Press, Singapore; Heng, op.cit.).

Those Chinese capitals and Indian compradors would, by forming joint ventures with Malay capitals, tap upon the vast capital resources of State agencies such as PERNAS, PNB and Peremba Bhd, besides

- UMNO-controlled corporations like the Fleet Group and Media Prima

- Institutional funds such as Lembaga Urusan Tabung Haji (LUTH or Islamic Pilgrims Management and Funds Board) and Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera (Armed Forces Funds Board)

- Private sector capital held by new class of Malay millionaires such as Tun Daim Zainuddin, Tun Sri Azman Hashim, Tan Sri Wan Hamzah and Tun Sri Rashid Hussein

- As well as royal entrepreneurs like Tunku Imran ibni Tuanku Ja’afar of Negeri Sembilan and Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar of Johore whose latter’s wealth as estimated by Bloomberg with a conservative worth around US$5.7 billion, and the royal family’s due US$1.1 billion investment portfolio, which includes US$105 million worth of investments in public companies, US$483 million worth of investments in other private companies, and various real-estate projects.

EPILOGUE

With the birth of government-linked companies (GLCs) and the rearing of an ethnocapital-ethnocratic-clientel-capitalism class, therefore, after six and half decades despite of sustained neoliberalism economic developmental effort, the nation of Malaysia is still as disparity in absolute income inequality as ever, (see lower right chart below):

Sources: World Bank datasets and DoSM statistics

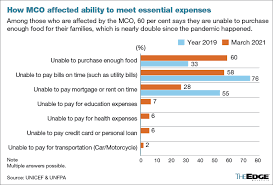

It is also an era of a generation when 70% of lower-income households cannot even meet monthly basic needs – indeed, more than 60% of these households reported having no savings at all – not much of any difference more than 10 years ago:

According to the Employees Provident Fund, over two million contributors aged between 40 and 54 have less than RM10,000 in their retirement savings accounts whereas the top well-off 1.7% of depositors have more accumulation than the entire savings of bottom 57% of depositors; and where,increasingly, these household expenditures are expansively spent just on food alone:

Thus, the nation of Malaysia is still encasted in acutely absolute income inequality as ever.

As an instance, Bantuan Tunai Rahmah, the cash aid scheme, reportedly has 8.7 million recipients – a quarter of the population – which gives a damning statement on the extent of low incomes among our workers. Directly, it is the concurrent exploitation of labour under capitalism and the deepening penetration in global financialisation of capital imperialism.

Related Readings

2. Unequal Exchange under Neo-Imperialism

3. Ethnocapital capitalism in calamity crisis

You must be logged in to post a comment.