20th February 2023

1] INTRODUCTION

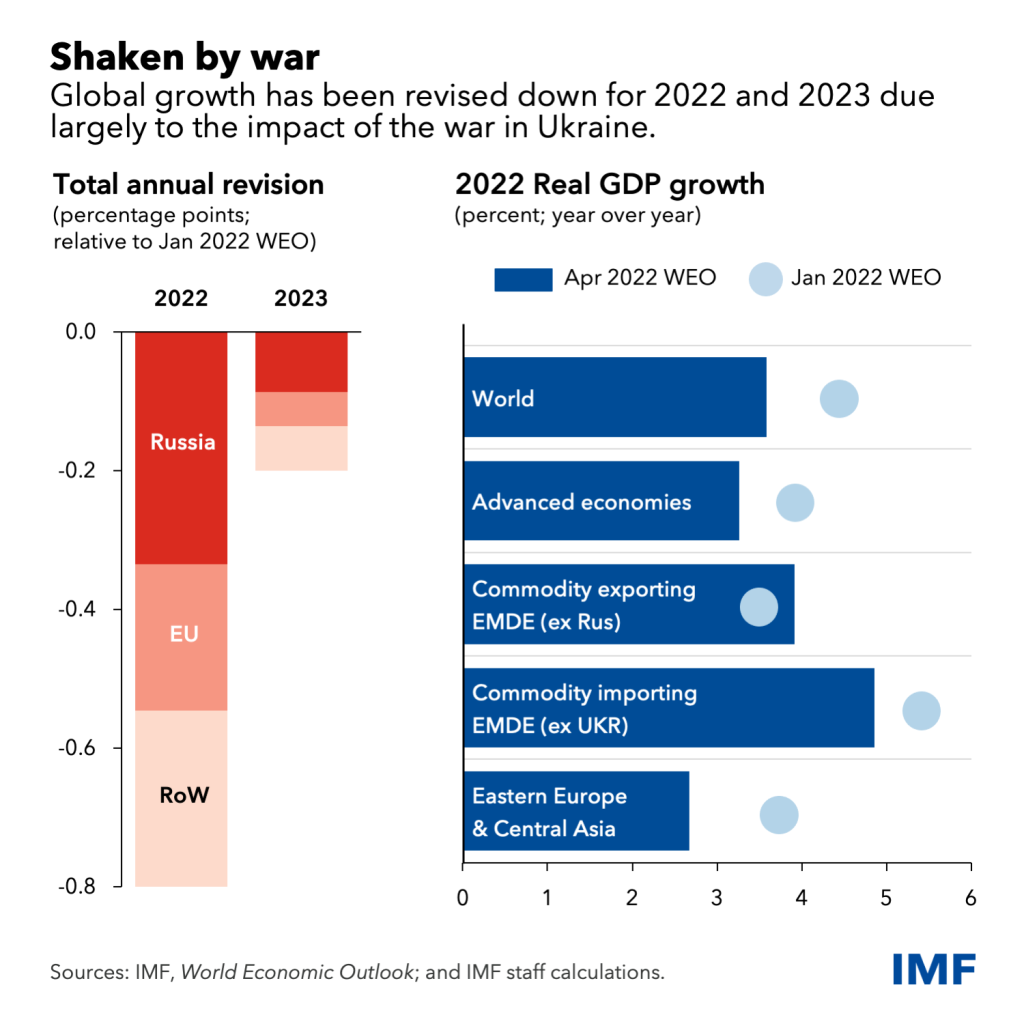

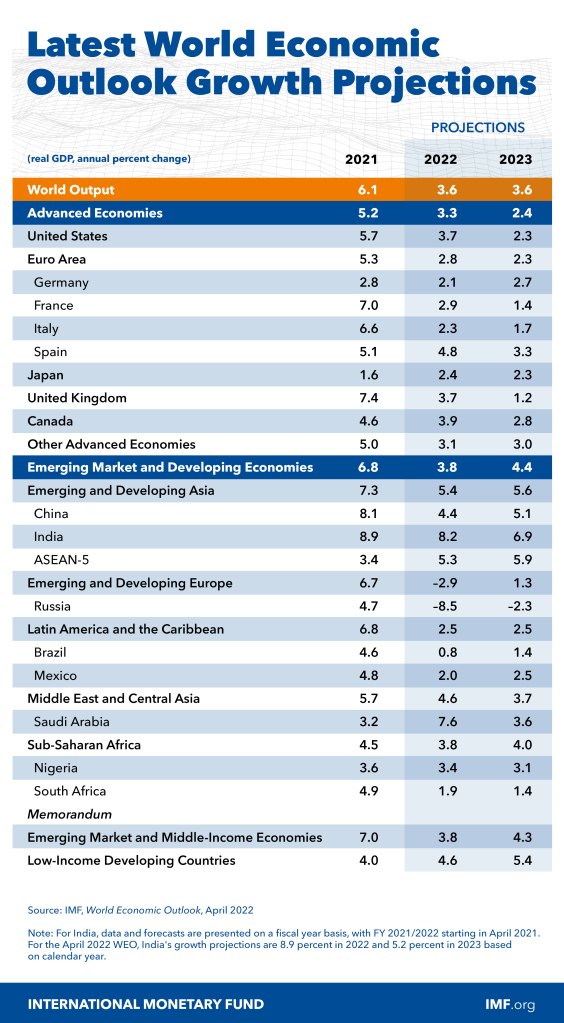

As global growth is likely to decelerate sharply to 1.7 percent in 2023 synchronous with policy tightening, worsening financial conditions, and continued disruptions from the Russia near-border conflict, the activity in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDE), excluding China, is forecasted to slow from 3.8 percent in 2022 to 2.7 percent in 2023 on account of weaker external demand and tighter financing conditions.

2] STATE OF NATION

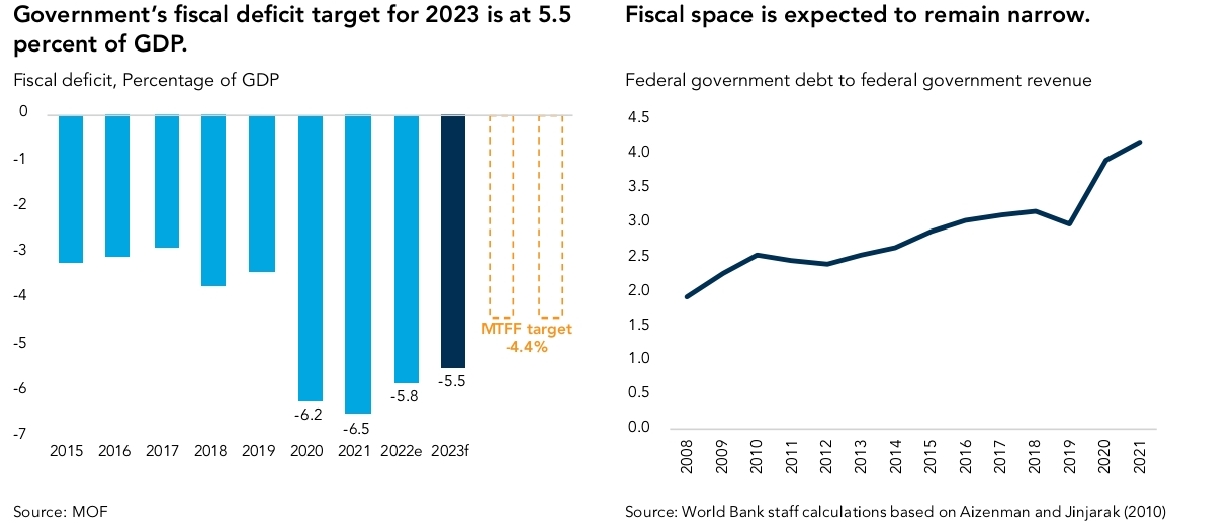

With government revenue projected to remain low and structural expenditures still increasing high, this has led to further narrowing of Malaysia’s fiscal space (see right chart below):

Using the ratio of the Federal Government Debt to the revenue collection as a reference point, the World Bank has indicated that Malaysia’s fiscal space has gradually narrowed since 2012 and became tighter post-pandemic.

The government’s medium-term fiscal consolidation plan is guided by its Medium-Term Fiscal Framework (MTFF). Under the latest MTFF for 2023-2025, the government has adopted from the previous MTFF estimate, based on a projection that nominal GDP will expand by an average annual rate of 5.5 percent, and that the average price of crude oil will maintain at US$90 per barrel. As with the previous MTFF, the current framework pursues an expenditure-driven fiscal consolidation, (see chart above: left side).

The government expects operating expenditure to decline from 15 percent of GDP in 2023 to around 14.5 percent over the MTFF period.

The government also expects revenue to decline over this period, from 15 percent of GDP in 2023 to an average of 14.7 percent in 2023-2025. Overall, the fiscal deficit is expected to consolidate at a gradual pace with the overall balance averaging at 4.4 percent of GDP for the MTFF period.

The current fiscal consolidation strategy – via spending reduction – is, to many national economists and political analysts, rather challenging, given the current tight spending domain.

Firstly, the combined spending on structural expenditures is already at high levels; and secondly, other Operating Expenditures components such as supplies and services, and grants and transfers have been on a declining trend or are already at low levels.

Therefore, the government’s current fiscal consolidation plan would have to include a higher revenue collection target.

Through preceeding regimes’ gorging and siphoning – and depleting – of national wealth, whereupon revenue level has remained low and is still trailing comparative peers. It is more than ever importantly to address the persistent decline in revenue collection and explore new sources of revenue, more so under an inflationary trend that affect every poor people of the low-incoming developing countries.

3] SOURCES OF DEVELOPMENT REVENUE

A) Sovereigns can borrow from within their own country or from abroad.

Domestic borrowing – from local banks and asset managers or directly from households (EPF employees’ money or PNB owners’ saved trust units) could likely be a steady and reliable source of financing. However, there is a limited amount of money available and repayment maturities tend to be short. Not infrequently, governments also borrow from international capital markets, in larger amounts and usually at longer maturities.

Otherwise, there is a wide and diverse range of private sector entities willing to lend to sovereigns, too. Asset managers, such as pension funds, typically hold a large amount of government debt. They need relatively safe long-term assets to match their long-term liabilities.

B) In big ticket projects, they have been financed typically through government budgets, either from tax revenue or from government borrowings, some had often been financed through special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) — for example, DanaInfra, which was set up to raise financing for several infrastructure projects. The debts of these SPVs are guaranteed by the government, and hence, can be considered ultimately as government debt.

Many public infrastructure projects have also been privatised, and the private investors would recover their cost of investment through collecting tolls or charges from the users. Examples of these include the toll roads, independent power producers and land-swap projects. In such cases, the government does not carry any liability for these projects unless it has given some form of revenue guarantees to these private investors. This financing model (using private-sector finance and project development expertise) is known as a public private partnership (PPP).

Not often publicised is another variant of PPP, where private investors recover their cost of investment through payments from the government. This is generally known as a private finance initiative (PFI) which has its many odious transactions. PFI payment obligations comprise a large proportion of the PPP debt of RM$201.4 billion, which was only known, and later announced, by the preceeding government in May, 2022, (read PFI, 2022).

C) Inevitably, instead of borrowings that incurred interests, a progressive way is to implement a windfall tax on industries that benefit greatly during the Covid-19 crisis, according to Khazanah Research Institute senior advisor Professor Dr Jomo Kwame Sundaram.

“This is precisely the time when you must reform taxes as you have it (windfall tax) all the time amid extraordinarily high petroleum prices or palm oil prices.”

This is concurred by Institute of Malaysian and International Studies research fellow Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid who pointed out that policy-makers tend to ignore the imposition of capital gains tax when it comes to the issue of tax reform.

Even Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) assistant governor Dr Norhana Endut noted that the government’s tax collection capacity had not kept pace with the economic growth.

Indeed, Malaysia tax to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio, has been on a steady decline over the medium term. It fell to 12% in 2019 from 15.6% in 2012.

Further, Malaysia’s individual income tax also continued to come from a narrow pool of taxpayers. For instance, in 2018, among a labour force of 15 million people, only 2.5 million were taxpayers!

There is a definite need in expanding the tax base be a priority over the medium term, besides existing tax incentives and exemptions should be reviewed on a regular basis as some of them are outdated and ineffective, affecting the beneficial economic development among the marginalized poor’s.

This is also during an era of inflationary trend. Global inflation is expected to fall to 6.6 percent in 2023 and 4.3 percent in 2024, still above pre-pandemic levels, thus socio-economic impacting heavily on the B40 rakyat².

According to Richard Record, one-time the World Bank Group’s lead economist for Malaysia, the country needs to raise more revenue and spend it more effectively. “Malaysia, of course, benefits from having oil and gas revenues as a source of non-tax revenue, but these have tended to be quite volatile,” he tells The Edge.

Present revenue collection is low mostly because rates are low and there are so many allowances and exemptions. Reforming the SST (Sales and Services Tax), and in particular sharply reducing the number of non-essential items that are zero-rated or exempted from.

Indeed, there should be greater effort across tax instruments: to increase the progressivity of personal income tax, re-examine the number and targeting of corporate income tax incentives and to consider new sources of revenue such as environmental taxation and capital gains taxation.

The introduction of capital gains tax, raising the tax rate for those in the top individual tax bracket and imposing a tax on retirement savings above a certain threshold were among the suggestions on how to enhance revenue in the World Bank Report, 2021.

If the present Government continues to borrowing – the interest rate has to be minimal – then it has to prevent the structure of such debts from becoming too risky. This is because, at one time, we find it cheaper to borrow in US dollars or euros than in our own currency. However, this finanancial method can cause problems if the ringgit depreciates because this increases the real burden of the debt – as was clearly exemplified proportionately in the 1MDB case:

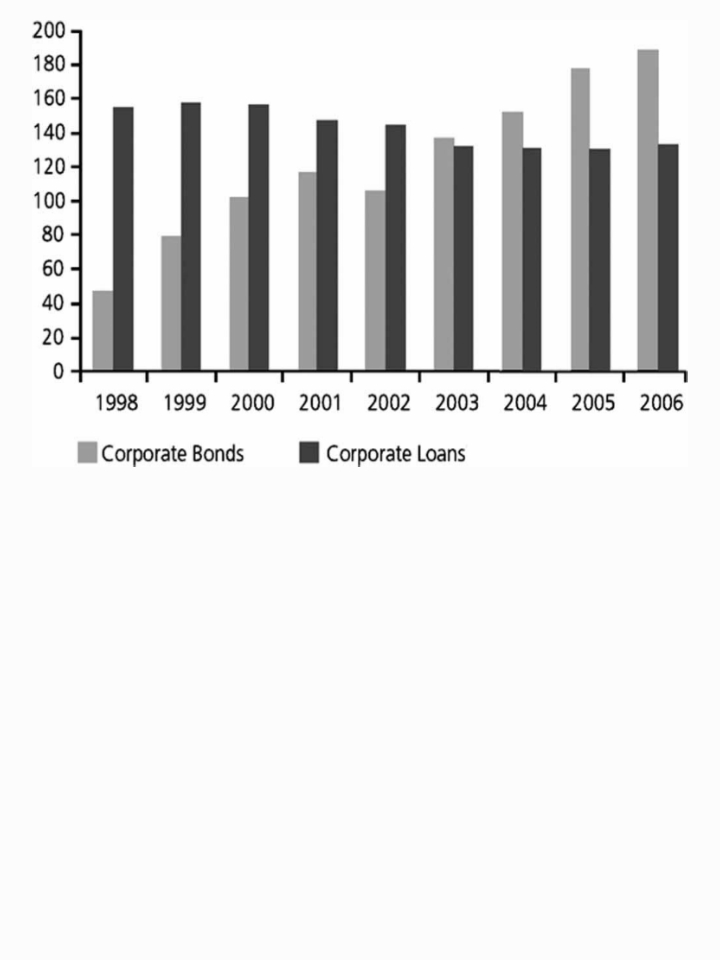

D) Otherwise, it is to apply traditional methods like using Government bonds issued to finance budget deficits but with a glaring pitfall. If there is a continuous growth of debt, the private sector creditors may become concerned about the government’s initiative to repay it. Over time, these creditors will expect higher interest payments to provide a greater return for their increased perceived risk as it is widely acknowledged that higher interest costs dampen economic growth.

On the other hand, for Danaharta it uses cash to purchase loans from the domestic banking system by paying sharp discounts of as much as 50 per cent on a loan that was either collateralised by property or shares listed on the stock exchange.The consequence is too much liquidity in the matket, and the country went south can be partly identified to the solidification of financialisation capitalism (see: Southampton’s Lena Rethel Financialisation and the Malaysian Political Economy.

The flooding of money in the market is not to generate wealth but within the circuit of financialization capitalism components of FIREs (finance, interests, real estate) in furtherance of repaying mortgage loans, hire purchases, insurances, real estates tax dues and other debt interests.(Rajah Rasiah, 2011) has ambly demonstrated that with accentuated and expanded monetary instruments circulation, the national economy had impaired, through wide currency circulation, unfavourably:

E) Inheriting such a burgeoning debt burden, sovereign wealth fund Khazanah Nasional Bhd could sell its assets to raise cash for the state of a nation as she is sitting on assets easily worth more than US$30.5 billion (December 2021) that could probably raise over 10% of the government’s +RM$1.5 trillion debt and contingent liabilities.

Another financial resource lies with Petronas as it is financially in a comfortable position to pay, given that its total assets has strengthened to RM$699.5 billion in the first half of 2022.

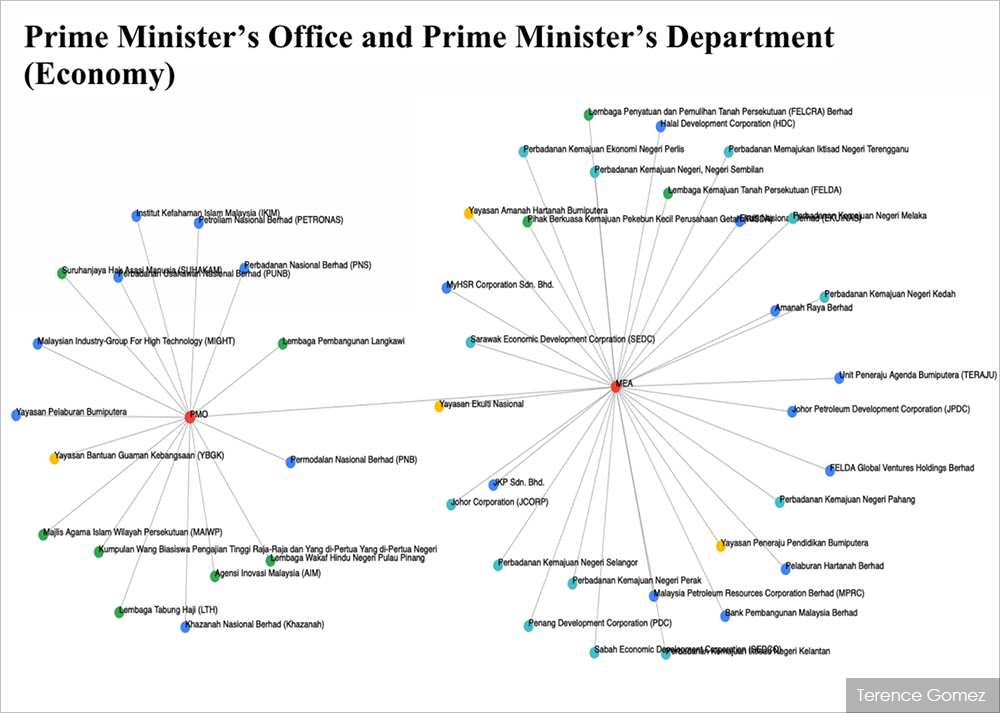

Alternatively, government-linked companies (GLCs) and government-linked investment corporations (GLICs) would also likely be encouraged to pay higher dividends. The government could tap these state enterprises to help out just as like the recent RM$58 billion stimulus package to counter impact of the Covid-19 pandemic 2020 crisis.

4] PROGRESSIVE PATH PROCESS

From The Quest for Growth (World Bank, 2016), and to Surge Ahead (World Bank 2021), the country is still, catastrophically, mired and entrapped within capitalism crisis to crisis in a struggle to Catching Up, (World Bank, 2022) among ASEAN peers:

To undertake an emancipatory project may necessarily has to migrate pass through various revolutionary socio-economic phases such the community-based projects of various scopes, scales and dimensions, (see chi-sigma, Towards a Socialist Community with Solidarity Involvement as one such possible undertaking).

To be successful, therefore, requires a commitment to a pulsating socio-economic change that seeks to make itself irreversible through the promotion of an organic system directed at genuine human needs, rooted in substantive equality and the rational regulation of the human social metabolism with nature.

In building an equity society with socialism as the dominant foundation, we must do all we can to develop the productive forces and gradually eliminate poverty, constantly raising the people’s living standards. Only when this outcome is achieved and there is significant prosperity for all will it become possible to begin the shift to advanced stage of an economy that is highly developed and where there is overwhelming material abundance. Only by this process that we shall be able to apply the principle of from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

To achieve this process, there is a need on genuine planning and genuine democracy where these are through the constitution of power from the bottom of society. It is only in this way that a progressive socioeconomic society, and its healthy and well-being domain, becomes irreversible.

Towards this process in striving the Socialism with Malaysia characteristics goal, there shall be a combination of planning and markets forming the basic socialist economic system. Second, we need to keep in mind the dialectical relation between ownership and the liberation of the productive forces that shall entail; thus

(1) the system contains a multiplicity of components, but public ownership remains the core economic driver, with corporate capitals supplementing capital formation but without undue surplus value extracted from labour;

(2) while both state owned and private enterprises must be viable, their main objective is not profit at all costs, but social benefit that meets ‘people-centred’ needs from appropriate shelter, education equity to community-base healthcare, adequate nutrient food, harnessing modern technologies towards social needs;

(3) it employs the primary socialist principle of from each according to ability and to each according to work, limiting exploitation and wealth polarisation, and ensuring common prosperity and wealth sharing for every rakyat2 wellbeing;

(4) the primary value should always be ‘socialist collectivism’ – gotong royong community-based than bourgeois individualism and inflicted neoliberalism ethos.

5 CONCLUSION

The emergence of such socialist democratic political practice shall embrace an organic unity of the components of socialist democracy which entails that the people are masters in, and within, the community supervising the servants of society through the socialist rule of law and the Federal institutional guarantees.

We need to be in the threshold of a new sovereignty re-imaging a New Malaysia positioning an entity adhering a New Narrative to perform New Politics for the generasi muda.

This is the moment of great re-imaging of the Malaysia nation and possibly the greatest challenging changes to be seen since independence gained. This is the basic starting point of all planning work and the tasks ahead.

This is that moment of the momentum of a movement.

– □□□ –

Related Readings

Reforming Malaysia’s Government Finances

Ramesh Chander, Murray Hunter, and Lim Teck Ghee

You must be logged in to post a comment.