20/07/2022

1. INTRODUCTION

Recently there are a number of content materials debunking the debt trap diplomacy myths in Sri Lanka and Africa. What is often not stated is the insidious role played by other private capital actors, too.

There are in a number of developing economies today when debt restructuring cannot inevitably occur without the full participation of foreign private creditors.

2. THE BOND-HOLDERS

Indeed, the low- and middle-income economies owed, at the end of 2021, an estimated US$9.3 trillion to foreign creditors, mostly to private creditors and trans-bordering bondholders hovering globally across multiple countries. Since majority of the outstanding payable is private debt, more often than not, bondholders would consciously purchase the right to collect in secondary markets, too, at times very much like vultures in a kill-feed.

Among this flock of bondholders, a small minority are regarded as vulture investors. They tend to focus on the distressed debt of governments, buying their bonds at a deep discount with the ultimate goal of suing a ruling government to collect the full payment.

These investors have little incentive to participate in debt-relief initiatives. To maximize their return, they hold out until other creditors make concessions – in the expectation that concessions from others will free up cash that enables the holdouts to collect the biggest possible payoff.

This is an unadulterated form of free-riding that hurts all other creditors, too.

3. THE GOVERNING BODIES

Governments have an invoking public interest to end this imbalance on such unfair transactions. It is timely, and a long-overdue process, for national governance stepping up to protect rakyat2 from third party monopoly-capital financial capitalism exploitation which directly is an expropriation of national wealth in Global South countries.

Granting distressed governments even a few of the legal protections routinely granted to distressed businesses would fix much of the problem. However, enacting them in just a few jurisdictions – like in Global North New York and London, for example – would only perpetuate the sovereign-debt contracts of developing economies as governed by the laws of these monopoly-capital financial centres.

The Common Framework – the debt restructuring program endorsed by the G-20 for 73 of the world’s poorest countries – might be one good approach to try out their alternative techniques.

Under the terms determined by the Paris Club, non-ODA (Overseas Development Aids) claims can be written off in whole or in part, while ODA claims are restructured.

However, ODA poses more problems than it solves.

First, the amount.

Since 1970, developed advanced country (DAC) members had committed themselves to devote a minimum of 0.7% of their gross national income (GNI) to ODA. However, this threshold has never ever been reached. In 2019, total ODA was estimated at $155 billion, that is, only 0.3% of DAC GNI. This amount pales in comparison with the $485 billion remitted by the diasporas to developed countries during the same period.

Second, its composition.

Contrary to what its title would suggest, ODA is not unconditional, disinterested and “humanistarian” aid. It is composed of grants but also of so-called “concessional loans”. It is therefore not uncommon for the annual net transfer of ODA for a “recipient” country to be negative. Similarly, the country is not free to use these sums as it sees fit, but is subject to a programme defined by the donor countries and/or international institutions.

Finally, its opacity.

According to the data provided by the OECD, it is not possible to separate aid in the form of grants from aid in the form of loans. In order to artificially inflate its figures, the OECD has created a “grant-equivalent” category that includes not only said grants, but also low-interest loans with a long repayment period in order to supposedly better “reflect the real effort made by donor countries”.

see 2003 article by Damien Millet, “L’initiative PPTE : entre illusion et arnaque”: https://www.cadtm.org/L-initiative-PPTE-entre-illusion-et-arnaque (in French)

In fact, the application of large-scale statutory process such as the Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism is most of the time regarded as being defeated by its own ambition. Indeed, those recommendations by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund are no more than loan-sharking along2 preying on unfortunate victims.

4. THE DEBTORS

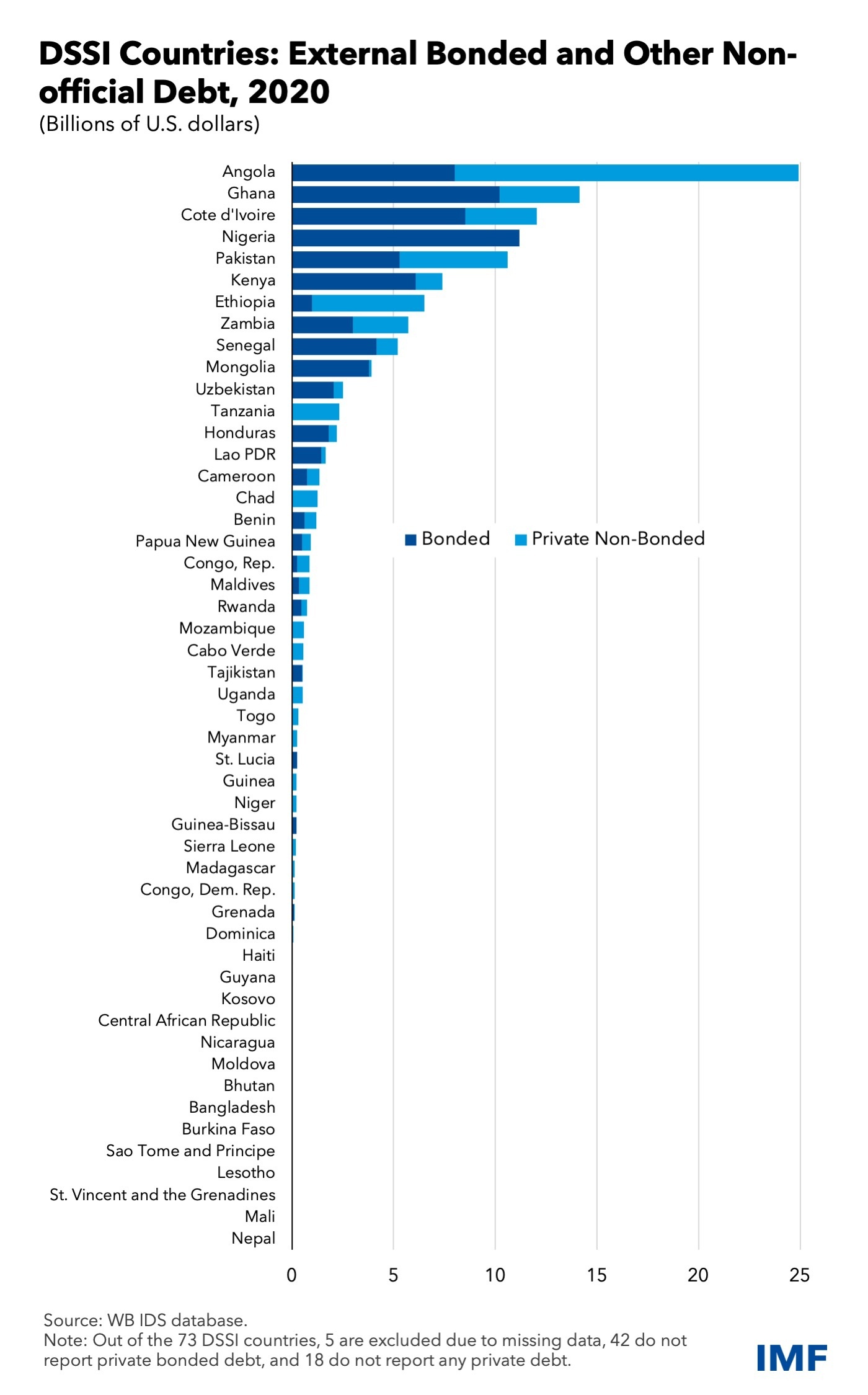

Sub-Saharan Africa is the region of the World that is the hardest hit by the IMF and its austerity policies ¹imposed through structural adjustment plans since the 1980s, the HIPC initiative since 1996 and since April 2020 the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). Among the worst hit countries are Côte d’Ivoire, Madagascar, Niger, Senegal, Congo (Democratic Republic) Togo and numerous Central African countries.

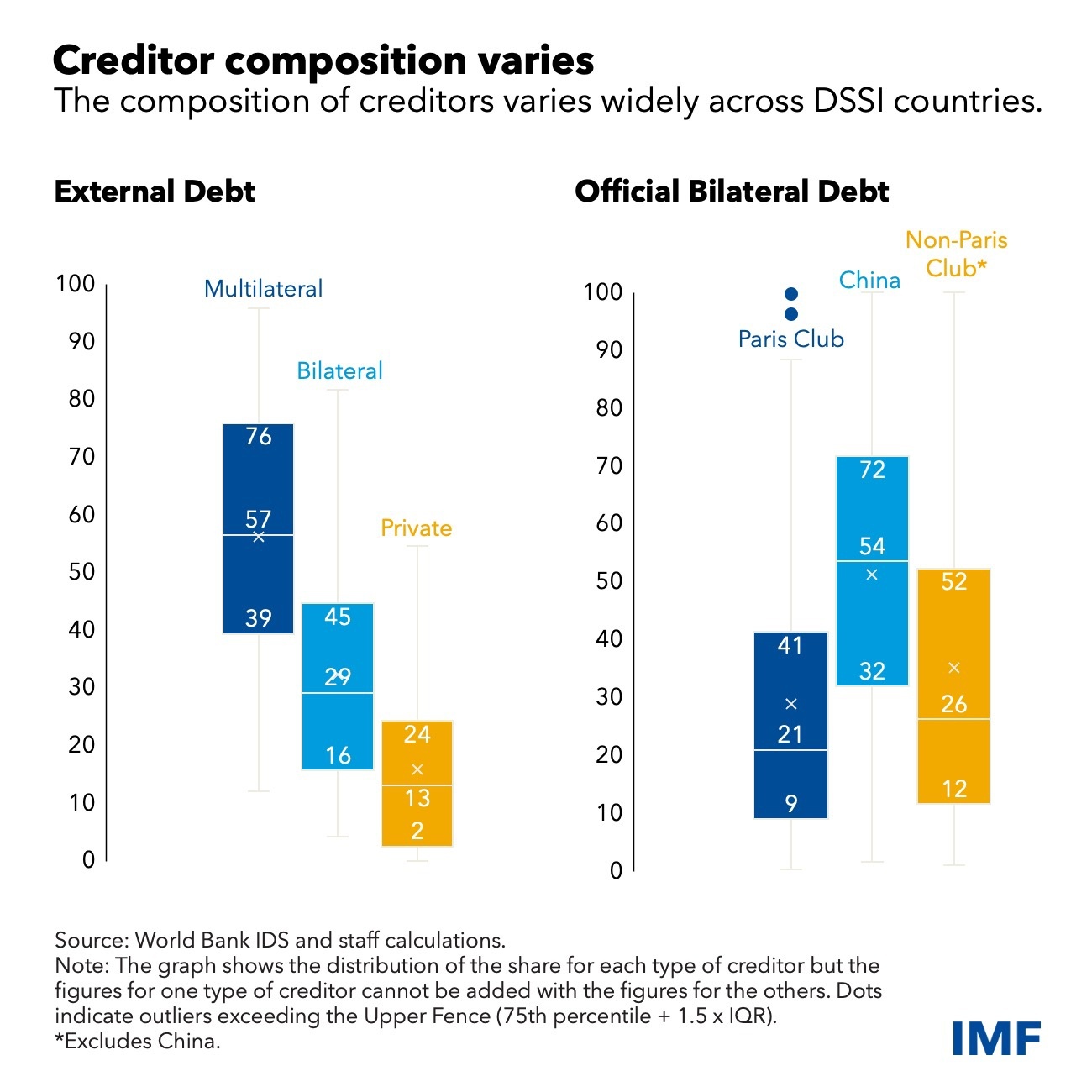

In a significant number of developing economies today, debt restructuring cannot occur without the full participation of foreign private creditors. Most of the private debt, moreover, is owed to bondholders who often, explored above, purchase the right to collect in secondary markets.

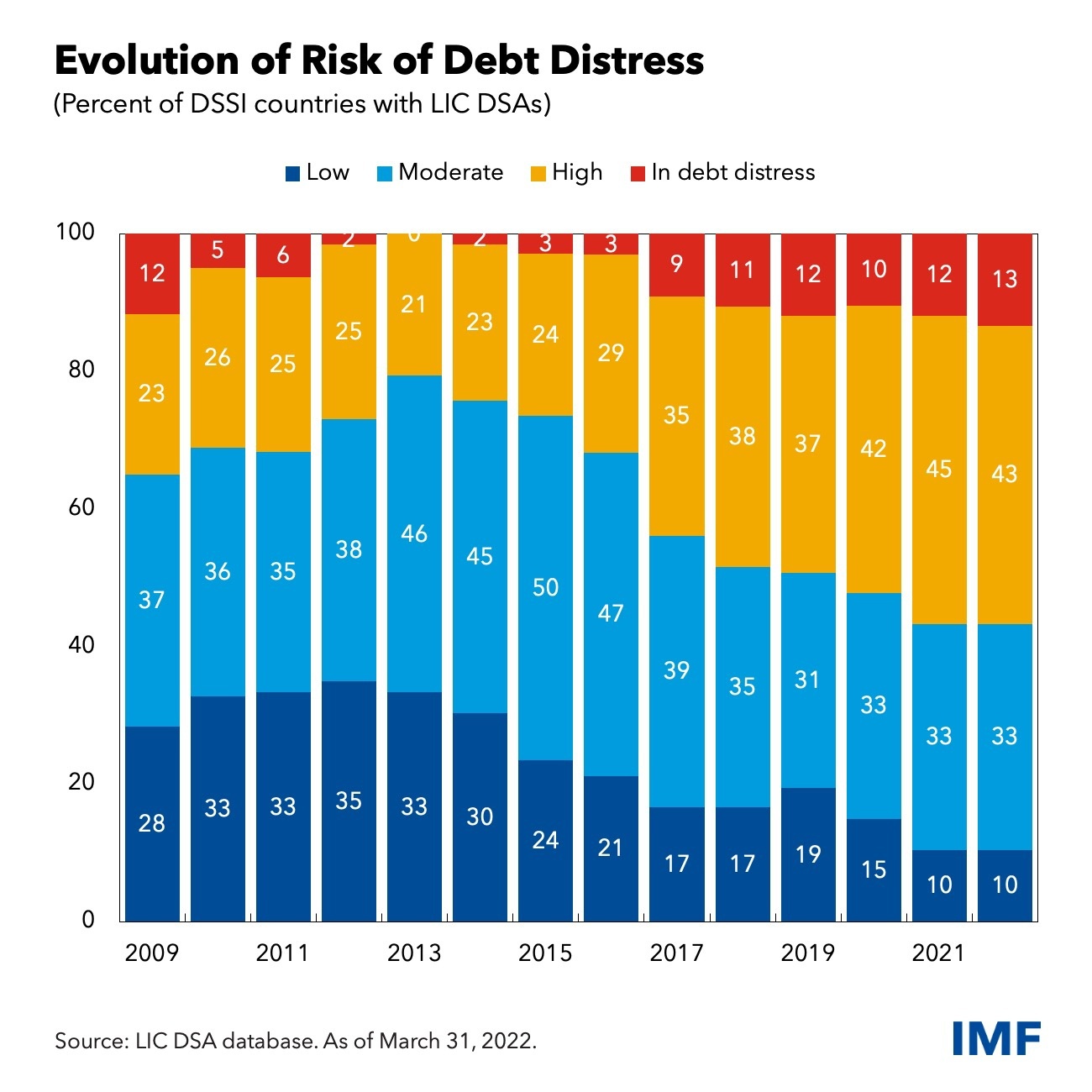

About 40 low-income economies and six middle-income economies are either in debt distress or at high risk of it. For both types of economies, there is only one pathway towards restructuring unsustainable debt. This is either through the Paris Club for middle-income economies and the G-20’s Common Framework for Debt Treatments for low-income economies

However, both approaches have certain process hurdles. Typically, In return for debt relief from foreign government creditors, borrowing countries would have to wrangle equivalent concessions from foreign private creditors – the vulture capitalists – over whom they have no bargaining power.

Not surprisingly, progress has encountered problematic barriers. For instance, just three countries – Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia – have sought relief under the Common Framework. More than a year after they applied, little administrative movement nor process resolution has been resolved adequately.

That is also consistent with the experience of the G-20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which urged (but did not require) borrowing countries to secure comparable concessions from private and government creditors alike. In the DSSI, only one “private” creditor participated, but that was simply a national development bank that identified itself as a private creditor.

4. CONCLUSION

The right to a second chance is enshrined in the corporate bankruptcy laws of most leading economies. Yet the same indulgence is denied to low-income governments with predictably grave consequences for the poorest rakyat2 in the poorest countries. At the end of 2021, governments in low- and middle-income economies owed an estimated $9.3 trillion to foreign creditors, mostly to private creditors and bondholders scattered across multiple countries.

For them, no bankruptcy court exists to ensure a prompt and orderly restructuring if a debt crisis approaches. Instead, they often have to pick their way through a procedural maze that is governed more by quaint conventions than by statute.

Governments have a compelling public interest to legislation to end this imbalance in foreign loan transactions. It is an overdue step to protect their own taxpayers from third party external monopoly-capital exploitation.

The time is urgent to rectify the imbalance in debt restructuring and its repayment. This is more imminently at a time when global growth downturns and interest rates are surging.

Consequently, the risk of a spate of debt crises is also rising – and yet the available mechanisms for tackling them are deeply inadequate and inappropriate because vulture capitalism flies high.

Time is also too short to permit the type of large-scale statutory solutions – such as the Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism – that are designed in reality by a cohort of neoliberalism-is-neo-imperialism entities.