Urban low-income families are much more likely to be unemployed or have lower working hours with lower pay, and greater challenges in accessing healthcare.

A. POVERTY AND DEBTS

The migration of low-income groups from rural into urban areas, the increase in unemployment and the influx of foreign workers have contributed to the rise in urban poverty, adding to pressures on urban services, infrastructure and the ecological environment. As a result, Malaysia poverty has become more urbanised.

The UNICEF 2020 Report has shown that low income female-headed households are exceptionally vulnerable, with higher rates of unemployment at 32% compared to the total heads of households. Female headed households also registered lower rates of access to social protection, with 57% having no access compared to 52% of total heads of households.

The recovery of low-income families in Kuala Lumpur has been partial and uneven, with many still struggling to purchase enough food for their families while an increasing number of households have no savings.

Indeed, the national household debt-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio had already surged to a new peak of 93.3% as at December 2020 from its previous record high of 87.5% in June 2020, according to Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM).

1] THE PERSISTENT POVERTY

i) That 7 in 10 households reported that Covid-19 had affected their ability to meet basic living expenses, with 37% saying they struggle to purchase sufficient food for their families. Another 35% are unable to pay their bills on time.

ii) That 68% of households had no savings, compared to 63% in December last year, while those who still had savings have seen the average figure decline by 35%. The situation is worse for female-headed households and heads of households with disabilities, where average savings are at RM342 and RM74, respectively.

iii) That while median household income has increased by 23% to RM2,233 in the months after strict restrictions on movement were lifted, the amount is still 10% lower compared to pre-crisis levels.

iv) That only 14% of heads of households expect their financial status to be better in the next six months, while 37% expect it to be worse. The majority remains pessimistic; though there are some signs of improvement compared to during the MCO.

Most families continue to pawn their valuables and have started to default on their rental payments as cash becomes scarce.

2] ENDURANCE IN EDUCATION

i) The restart of economic activities during the May to September 2020 had led to a 29% rise in monthly household expenditure, driven by spending on education and transport at 283% and 59% respectively.

ii) The extra expenses on education is also driven in part by face mask costs. About 38% of all heads of households and 46% of female-headed households reported difficulties in providing face masks to their children.

iii) About 65% of female-headed households find it difficult to provide pocket money, while 30% struggle to pay for transport fees.

iv) More of concern is a sizeable number of parents had said their children are demotivated, with nearly 1 in 5 parents reporting that their child had lost interest in school.

v) Online learning remains a major challenge due to the lack of suitable equipment. During the MCO, nearly 9 in 10 only used mobile phones as learning devices, and 8 in 10 had no access to computers.

vi) The majority of parents do not want their children to learn online, as cramped living conditions meant that their children had no place to study. Others cite a lack of internet access or no computer, laptop or tablet.

The study suggests that children from low-income families are at risk of dropping out of school as a result of the combined financial and psychological impacts of the crisis.

3] CHALLENGES ON MENTAL HEALTH

i) Mental health remains a significant concern as 22% of heads of households reported feeling depressed or that they experienced extremely unstable emotions.

ii) 42% are worried about their financial conditions, while 32% are worried about not having enough money to buy food for their children and to support their children’s education

iii) Some household members are also experiencing new negative behavioural changes, with 27% of female heads of households experiencing tension and depression among family members.

B. POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

rakyat2 loathe a prime minister who tells citizens are poor because they are lazy, despite working countless hours or a cabinet who tells labour to work two jobs when they are already working 60 hours a week, enraged at a minister who tells rakyat2 not to spend beyond means when they are underpaid and living below the poverty line.

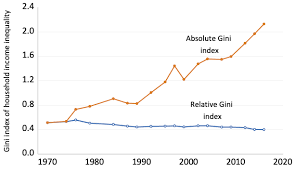

1] Where, according to the UNDP 1997 Human Development Report, and the 2004 United Nations Human Development Report, Malaysia has the highest income disparity between the rich and poor in Southeast Asia, greater than that of Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam and Indonesia.

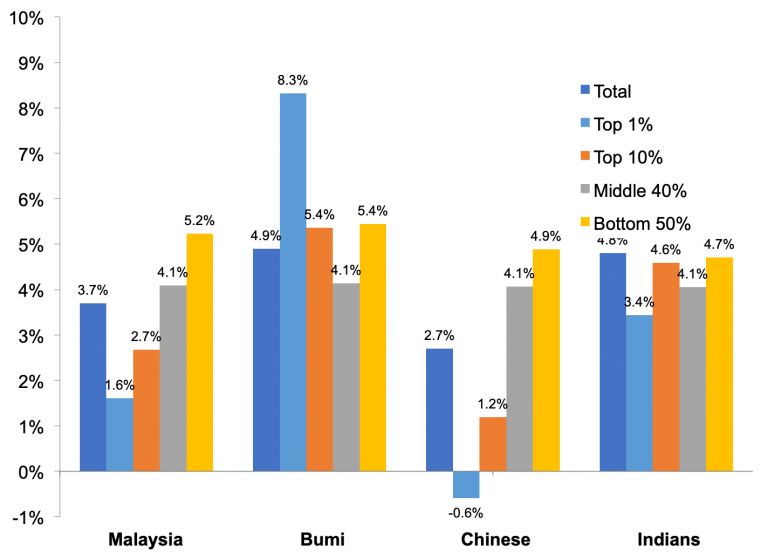

2] Where the share of the wealth is acutely benefitting the high-income group of capital-endowed class – especially the top 1% of bumiputera ethnocapital class is way above the national income, and of, other communities incomes, too.

3] Where the difference between income earned, and wealth disparity, had been accentuated through the years :

4] Where succeeding oligarchy regimes had continued maintaining a clientel ethnocapitalism domination over the working class rakyat2 with 1% of the bumiputera population (see Khalid lse.blog) or about 40,000 ethnocapital political families running and looting – and ruining – the national economy.

5] Where the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) figures released had shown that the average monthly salary and wage received by workers in the country was RM3,224 in 2019; a typical apartment in the Klang Valley is one hundred times say on this basic monthly salary. Presently, there is a total of about 10 million salary and wage recipients in Malaysia. The Household Income & Basic Amenities Survey Report 2019 by DOSM showed that the country’s 2019 median income of a household of four is RM5,873. This means it is sixty times of both parents’ monthly salaries to get a decent shelter.

To read: STORM, The Struggle for Shelter

On Engels thesis, present urban poverty reality has little to do with a lack of jobs or housing shelters , but rather it is firmly rooted in the mode of capitalism itself, and the exploitation and alienation of labour, upon which the system hinged.

C. THE CHALLENGES AHEAD

1] POVERTY ERADICATION

i) There is a need to eliminate the neoliberalism approaches towards economic development because the +60 years of a Neo-Imperialism dominated economy under monopoly-capital that connected with our clientel capital has stagnated the economy (Sudhdave 2020) and indebted the country where the unequal exchange of production has not eradicated, less of all eliminated, poverty in the country.

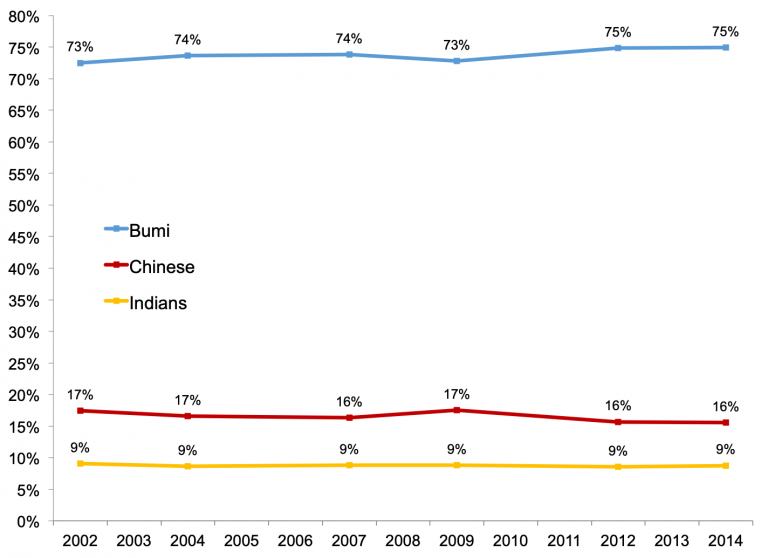

ii) Indeed, throughout the 2002-2014 period, the poor population among bottom 50 per cent of rakyat2 has been consistent, that is, we are ALL still poor: 73 per cent were still bumiputera, 17 per cent were Chinese, and 9 per cent were Indians:

iii) Presently, the top 20% of population – the T20 – possess 46.2% of the national income share, while M40 have 37.4% of the national income share but the bottom 40% of population – the B40 – only get 16.4% of the national income share of wealth.

2] DEBT MANAGEMENT

i) World Bank Group lead economist Richard Record had indicated that Malaysia has already depleted much of its available fiscal space and would emerge from the current pandemic crisis with a larger burden of debt and contingent liabilities despite the debt ratio had been approved by Parliament to increase from 55% to 60% of the gross domestic product (GDP). There would be difficult intertemporal constraints to further expand expenditures on relief and consumption-supporting stimulus over the near term.

This scenario shall leave national economy less endowed to invest in lasting recovery while maintaing growth in the future.

A paper published by the International Monetary Fund titled ‘Debt and Growth: Is There a Magic Threshold?’’ stated that countries with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 90 per cent and above could experience a dramatic decline in economic growth.

Even Moody Services had stated that the still-wide deficit for 2021 would increase the government’s fiscal consolidation challenge over the next few years. Further, any back-loading of efforts to reduce its debt burden over the year 2022 and 2023, will leave our national debt to the next generation of political leaders, and the present youth populace, to burden.

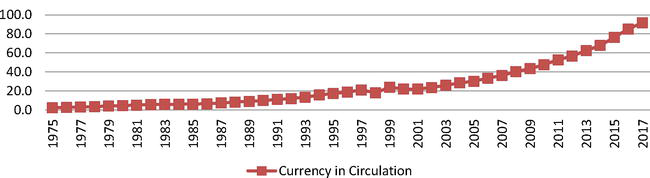

ii) Since 1997, the country had relied extensively on these Malaysian Government Securities for budget deficit financing where part of the budget deficits was financed by creating or printing new currency notes

(“helicopters’ monies”). Also part of the debt papers was monetized; therefore, money supply and currency in circulation increased sharply since 1999:

by Mohamed Aslam and Raihan Jaafar,

published: May 11th 2020

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen

In short, the amount of money floating around is not to generate wealth but within the circuit of financialization capitalism components of FIREs (finance, interests, real estate) are in furtherance of repaying mortgage loans, hire purchases, insurances, real estates tax dues and other debt interests.

iii) Therefore, it is contrary to reason that the government is more concerned with housing developers making high-rise profits than building affordable homes for ordinary Malaysians, particularly when one in four Malaysian families has yet to own a shelter. It is inconceivable, too, that a government refuses to increase the minimum wage (RM$1,200) when the poverty line is now almost double that amount at RM$2,208.

iv) It is difficult to believe that a country – rich in agriculutral resources, minerals endowment besides oil and gas reserves – has one in two of those with a monthly household income of below RM4,000 did not receive the Bantuan Sara Hidup Covid19 relief fund, while only 2% of the self-employed received the SME Special Grant.

v) The Employees Provident Fund (EPF) has revealed that out of Malaysia’s 22 million working-age population, 62% are self-employed, outside the formal labour force, and not covered by any form of social protection such as the EPF or government pension scheme.

Additionally, the low financial literacy rate of 36%, putting Malaysia well behind Singapore and Taiwan, leads to poor spending decisions. Indeed, 70% of Malaysians do not have a “rainy day” fund for emergency expenses, and subsequently high debt.

Yet, EPF contributors are urged to withdraw specific amount from their own accounts to sustain themselves during this stressful period than policy-makers be designing policies to address the deficient gap to reach the target groups as urged by Stephen Barrett, Unicef Malaysia’s social policy chief.

vi) Overall, social protection remains inadequate for low-income workers in the country, as 4 in 10 of those surveyed by the commissioned UNICEF and UNFPA longitudinal study – in partnership with DM Analytics, a Malaysia-based public policy and research led by Dr Muhammed Abdul Khalid – shows that low income families in Kuala Lumpur have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

The study showed that seven per cent of children residing in Kuala Lumpur’s low-cost flats are living in poverty

3] TOWARDS EQUITY AND EQUALITY

i) Short-term – operational – cash aid should be continued to be the most useful assistance for the majority of low-income families, for instance, with rental exemptions being equally helpful.

ii) Mid-term – tactically – Dr. Rashed Mustafa Sarwar, Representative for Unicef in Malaysia, said the country must take opportunities created by the budget and within the 12th Malaysia Plan to rethink social protection in Malaysia “to ensure that no family, and no child, is left behind” (see Towards A Post-2020 Political Economy; REFSA April 2021; blogs.World Bank 2021; PSM 2021, For a better Malaysia; Re-examining Urban Poverty : 2-hour webinar organised by the Center for Market Education, Embassy of Belgium and Bait Al Amanah, KualaLumpur, 15/4/2021).

iii) Long-term – strategically – we need to visionise on building communal organizations and governance to step onto a progressive path beyond capitalism and the capitalist state in economic development and socioeconomic management, and towards a socialist undertaking that shall benefit everyone than the few.

More Malaysian MANUSCRIPTS

°¤¤¤¤¤°

You must be logged in to post a comment.