Collective on Geoeconomics

4th September 2023

Preamble

In a previous mini-essay, we presented the positive argument of China’s socialism compared to the inherent imperfection in the U.S. capitalism system from a macro-economic perspective by applying the incremental capital output ratio (ICOR) principle that demonstrated the superior application of state-controlled entities and their processes compared to singular enterprise capital endowment. In this article, at a micro-level, we shall display some of China’s deployment of infrastructures and implementation of socio-economic provisions that enable an emerging economy surpassing a developed economy that is at a loss to its financialisation capitalism praxis.

[ A selective repost from The Unz Review ]

Look carefully at the chart below. What do you see?

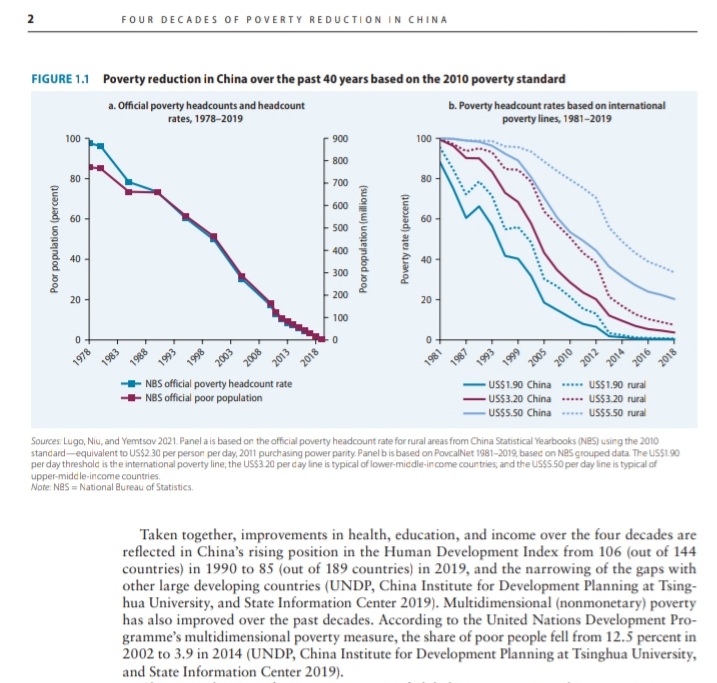

You see the development of a high-speed rail loop system that is unrivaled anywhere on earth. You see the actualization of plan to connect all parts of the country with modern-day infrastructure that reduces shipping costs, improves mobility and increases profitability. You see a vision of the 21st century in which state-directed capital links rural populations with urban centers lifting standards of living across the board. You see an expression of a new economic model that has lifted 800 million people out of poverty while paving the way for global economic integration.

You see an an industrial juggernaut expanding in all directions while laying the groundwork for a new century of economic integration, accelerated development and shared prosperity.

Is there a high-speed rail system in the United States that is comparable to what we see in China today?

No, there isn’t. So far, less than 50 miles of high-speed rail has been built in the United States. (“Amtrak’s Acela, which reaches 150 mph over 49.9 miles of track, is the US’s only high-speed rail service.”) As everyone knows, America’s transportation grid is obsolete and in a shambles.

But, why? Why is the United States so far behind China in the development of critical infrastructure?

It’s because China’s state-led model is vastly superior to America’s “carpetbagger” model. In China, the government is directly involved in the operation of the economy, which means that it subsidizes those industries that enhance growth and spur development.

In contrast, American capitalism is a savage free-for-all in which private owners are able to divert great sums of money into unproductive stock buybacks and other scams that do nothing to create jobs or strengthen the economy. Since 2009 US corporations have spent more than $7 trillion on stock buybacks which is an activity that boosts payouts to rich shareholders but fails to produce anything of material value. Had that capital been invested in critical infrastructure, every city in America would be linked to a gigantic webbing of high-speed rail extending from “sea to shining sea”.

But that hasn’t happened, because the western model incentivizes the extraction of capital for personal enrichment rather than the development of projects that serve the common good.

In China, we see how fast transformative changes can take place when a nation’s wealth is used to eradicate poverty, raise standards of living, construct state-of-the-art infrastructure, and lay the groundwork for a new century.

Here’s more from a report by the Congressional Research Service on “China’s Economic Rise…”

Since opening up to foreign trade and investment and implementing free-market reforms in 1979, China has been among the world’s fastest-growing economies, with real annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaging 9.5% through 2018, a pace described by the World Bank as “the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history.” Such growth has enabled China, on average, to double its GDP every eight years and helped raise an estimated 800 million people out of poverty. China has become the world’s largest economy (on a purchasing power parity basis), manufacturer, merchandise trader, and holder of foreign exchange reserves…. China is the largest U.S. merchandise trading partner, biggest source of imports, and the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury securities, which help fund the federal debt and keep U.S. interest rates low.( source: China’s Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States, Congressional Research Service.)

Here’s more from an article at the Center for Strategic and International Studies titled Confronting the Challenge of Chinese State Capitalism:

China now has more companies on the Fortune Global 500 list than does the United States… with nearly 75 percent of these being state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Three of the world’s five largest companies are Chinese (Sinopec Group, State Grid, and China National Petroleum). China’s largest SOEs hold dominant market positions in many of the most critical and strategic industries, from energy to shipping to rare earths. According to Freeman Chair calculations, the combined assets for China’s 96 largest SOEs total more than $63 trillion, an amount equivalent to nearly 80 percent of global GDP; see also China Socialism Efficiency

And here’s one more from a report by the IMF titled “Asia Poised to Drive Global Economic Growth, Boosted by China’s Reopening”:

China and India together are forecast to generate about half of global growth this year. Asia and the Pacific is a relative bright spot amid the more somber context of the global economy’s rocky recovery.

In short, the Chinese state-led model is rapidly overtaking the US in virtually every area of industry and commerce, and its success is largely attributable to the fact that the government is free to align its reinvestment strategy with its vision of the future. That allows the state to ignore the short-term profitability of its various projects provided they lay the groundwork for a stronger and more expansive economy in the years ahead. Chinese reformer Chen Yun called this phenom the “birdcage economy”, which means the economy can “fly freely” within the confines of the broader political system. In other words, the Chinese leadership sees the economy as an instrument for achieving their collective vision for the future.

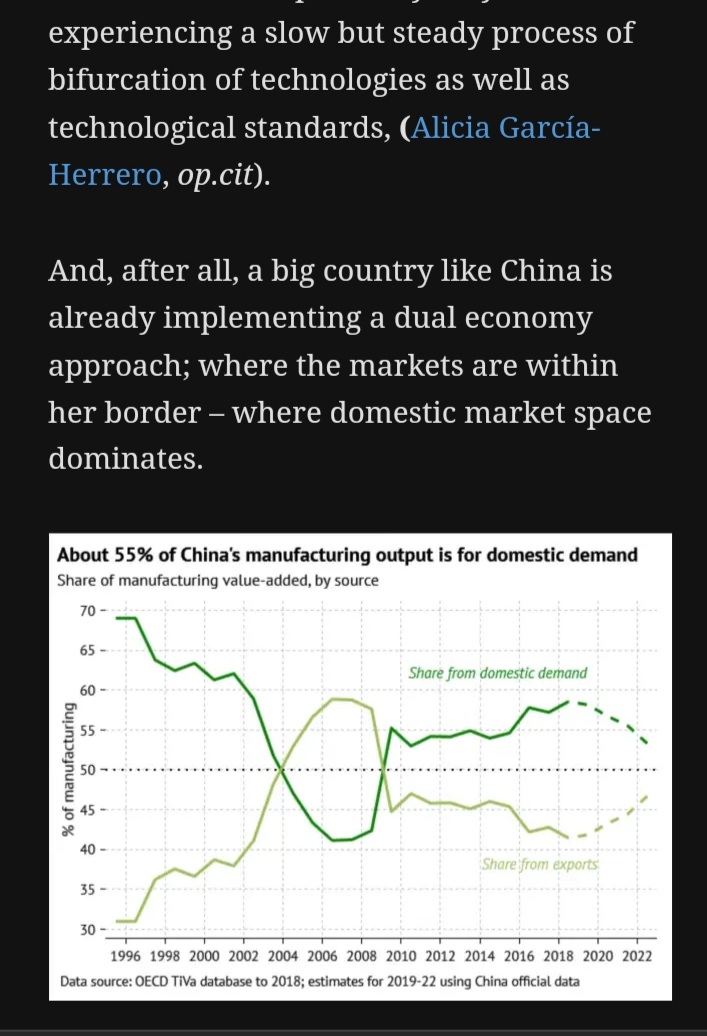

China’s success is only partially due to its control over essential industries, like banking and petroleum. Keep in mind, “the share of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in the total number of companies in the country has dropped to just 5%, though their share of total output remains at 26%.” And even though the state sector has shrunk dramatically in the last two decades, Chinese President Xi Jinping has implemented a three-year action plan aimed at increasing competitiveness of the SOE’s by transforming them into “market entities” run by “mixed-ownership.” Simply put, China remains committed to the path of liberalization despite sharp criticism in the West.

It’s also worth noting that the so-called Chinese Miracle never would have taken place had China implemented the programs that were recommended by the so-called “western experts”. Had China imposed the radical reforms (like “shock therapy”) that Russia did following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, then they would have experienced the same disastrous outcome. Fortunately, Chinese policymakers ignored the advice of the western economists and developed their own gradual reform agenda that produced success beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. The story is summarized in a video on You Tube titled “How China (Actually) Got Rich”. I have transcribed part of the text below. Any mistakes are mine:

The single most stunning economic story of the last few decades has been the rise of China. From 1980 to 2020, China’s economy grew more than 75-fold…. It was the largest and most rapid improvement in material conditions in modern history…. China had been one of the poorest countries on earth but now it is an economic powerhouse… Economists predict it will overtake the US as the largest economy in the world by the end of the decade. People call it The Chinese Miracle. Some people describe this miracle as a straightforward story of the “free market”. They say “it’s a simple story. China was poor (but) then the economy was freed from the grip of the state. Now China is rich.” But this is misleading. China’s rise was NOT a triumph of the free market. ...

Since the 1980s, free market policies have swept the globe. Many countries have undergone far-ranging transformations. Liberalizing prices, privatizing entire industries, and opening up to free trade. But many of the economies that were subjected to the market overnight have since stagnated or decayed. None of them have had a growth record like the one seen in China. African countries experienced brutal economic shrinkage. Latin American countries experienced 25 years of stagnation. If we compare China to Russia, the other giant of Communism in the 20th Century, the contrast is even more staggering.

Under state socialism, Russia was an industrial superpower while China was still largely an agricultural economy. Yet during the same period that Chinese reforms led to incredible economic growth, Russia’s reform led to a brutal collapse. Both China and Russia had been economies that were largely ordered through state commands. ….Russia followed the recommendations of the most “scientific economics” at the time, a policy of so-called “shock therapy” As a basic principle, the idea was that the old planned economy had to be destroyed, to make space for the market to emerge…. Russia was expected to emerge as a full-fledged economy overnight. …When Boris Yeltsin took power he eliminated all price controls, privatized state-owned companies and assets, and immediately opened up Russia to global trade. The result was a catastrophe. The Russian economy was already in disarray, but shock therapy was a fatal blow. (Western economists) predicted some short-term pain, but what they didn’t see coming was how severe and destructive the effects would be. Consumer prices spiraled out of control, Hyperinflation took hold, GDP fell by 40%.

The shock therapy slump in Russia was deeper and longer than the Great Depression by a large margin. It was a disaster for ordinary Russians…. Alcoholism, childhood malnutrition and crime went through the roof. Life expectancy for Russian men fell by 7 years, more than any industrial country has ever experienced in peacetime. Russia did not get a free market overnight. Instead, it went from a stagnating economy to a hollowed-out wreck run by oligarchs. If just getting rid of price-controls and government employment didn’t create prosperity but did destroy the economy and kill huge numbers of people, then clearly, the rapid transition to “free markets” was not the solution. …

Throughout the 1980s, China considered implementing the same type of sudden reforms that Russia pursued. The idea of starting from a clean slate was attractive, and shock therapy was widely promoted by (respected) economists… But in the end, China decided to not implement shock therapy. …Instead of knocking over the entire (economy) at once, China reformed itself in a gradual and experimental way. Market activities were tolerated or actively-promoted in non-essential parts of the economy. China implemented a policy of dual track pricing…. China was learning from.. the world’s most developed nations, countries like the US, UK, Japan and South Korea. Each of these managed and planned the development of their own economies. and markets, protecting early-stage industries and controlling investment.

Western free market economists thought this system would be a disaster …. But China’s leaders did not listen, and while Russia collapsed after following the “shock therapy” program, China saw remarkable success. The state kept control over the backbone of the industrial economy, as well as the ownership over the land.

As China grew into the new dynamics of its economy, state institutions were not degraded to fossils from the past, but were often the drivers at the frontier of new industries, protecting and guaranteeing their own growth. China today is not a free market economy in any sense of the word. It is a state-led market economy. The government effectively owns all land, and China leverages state ownership through market competition to steer the economy. The shock therapy approach advocated around the world was a failure.

The fact that China’s SOEs are shielded from foreign competition and receive government subsidies, has angered foreign corporations who think China has an unfair advantage and is not playing by the rules. That is certainly fair criticism, but it’s also true that Washington’s unilateral sanctions — which have now been imposed on roughly one-third of all the countries in the world — are also a clear violation of WTO rules. In any event, China’s approach to the market under Xi has been ambivalent at best. And while “the state sector’s share of industrial output dropped from 81% in 1980 to 15% in 2005”, (in the spirit of reform) Xi has also ensured that the CCP has greater influence in corporate management and corporate decision-making. Naturally, none of this has gone-over well with US and EU businesses titans who firmly believe that corporate stakeholders should rule the roost. (as they do in the West.)

The larger issue, however, is not that China subsidizes its SOEs or even that China is set to become the biggest economy in the world within the next decade. That’s not the problem. The real problem is that China has not assimilated into the Washington-led “rules-based order” as was originally anticipated. The fact is, Chinese leaders are strongly patriotic and have no intention of becoming a vassal-state in Uncle Sam’s global empire. This is an important point that political analyst Alfred McCoy sheds light on in an article at Counterpunch:

China’s increasing control over Eurasia clearly represents a fundamental change in that continent’s geopolitics. Convinced that Beijing would play the global game by U.S. rules, Washington’s foreign policy establishment made a major strategic miscalculation in 2001 by admitting it to the World Trade Organization (WTO). “Across the ideological spectrum, we in the U.S. foreign policy community,” confessed two former members of the Obama administration, “shared the underlying belief that U.S. power and hegemony could readily mold China to the United States’ liking… All sides of the policy debate erred.” In little more than a decade after it joined the WTO, Beijing’s annual exports to the U.S. grew nearly five-fold and its foreign currency reserves soared from just $200 billion to an unprecedented $4 trillion by 2013. (The Rise of China and the Fall of the US), Counterpunch.

Clearly, US foreign policy mandarins made a catastrophic error-in-judgement regarding China, but now there’s no way to undo the damage. China will not only emerge as the world’s largest economy, it will also control its own destiny unlike western nations that have been subsumed into the oligarch-led system (WEF) that decides everything from climate policy to mandatory vaccination, and from transgender bathrooms to war in Ukraine. These policies are all set by oligarchs who control the politicians, the media, and the sprawling deep state. Again, the issue with China is not size or money; it’s about control. China presently controls its own future independent of the “rules-based order” which makes it a threat to that same system.

If we look again at the first chart (above), we can understand why Washington rushed into its proxy-war with Russia. After all, if China was able to spread its high-speed rail network across all of China in just 12 years, what will the next 12 years bring? That’s what worries Washington.

China’s emergence as regional hegemon on the Asian continent is a near-certainty at this point. Who can stop it?

Not Washington. The US and NATO are presently bogged down in Ukraine even though Ukraine was supposed to be a launching pad for spreading US military bases across Central Asia and (eventually) encircling, isolating and containing China. That was the plan, but the plan looks less likely every day. And remember the importance that national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski placed on Eurasia in his classic The Grand Chessboard nearly 3 decades ago. He said:

“Eurasia is the globe’s largest continent and is geopolitically axial. A power that dominates Eurasia would control two of the world’s three most advanced and economically productive regions. ….About 75 per cent of the world’s people live in Eurasia, and most of the world’s physical wealth is there as well, both in its enterprises and underneath its soil. Eurasia accounts for 60 per cent of the world’s GNP and about three-fourths of the world’s known resources.

The consensus opinion among foreign policy mucky-mucks is that the United States must become the dominant player in Central Asia if it hopes to maintain its current lofty position in the global order. Former Undersecretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz went so far as to say that Washington’s “top priority” must be “to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival, either on the territory of the former Soviet Union or elsewhere, that poses a threat on the order of that posed formerly by the Soviet Union.” Wolfowitz’s sentiments are still reiterated in all of recent US national security documents including the National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy. The pundits all agree on one thing and one thing alone; that the US must prevail in its plan to control Central Asia.

But how likely is that now? How likely is it that Russia will be forced out of Ukraine and prevented from opposing the US in Eurasia? How likely is it that China’s Belt and Road Initiative will not expand across Asia and into Europe, the Middle East, Africa and even Latin America? Check out this brief excerpt on China’s Belt and Road plan:

China is building the world’s greatest economic development and construction project ever undertaken: The New Silk Road.The project aims at no less than a revolutionary change in the economic map of the world…The ambitious vision is to resurrect the ancient Silk Road as a modern transit, trade, and economic corridor that runs from Shanghai to Berlin. The ‘Road’ will traverse China, Mongolia, Russia, Belarus, Poland, and Germany, extending more than 8,000 miles, creating an economic zone that extends over one third the circumference of the earth.

The plan envisions building high-speed railroads, roads and highways, energy transmission and distributions networks, and fiber optic networks. Cities and ports along the route will be targeted for economic development.

An equally essential part of the plan is a sea-based “Maritime Silk Road” (MSR) component, as ambitious as its land-based project, linking China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and the Indian Ocean. When completed, like the ancient Silk Road, it will connect three continents: Asia, Europe, and Africa. (and, now, Latin America) The chain of infrastructure projects will create the world’s largest economic corridor, covering a population of 4.4 billion and an economic output of $21 trillion…

For the world at large, its decisions about the Road are nothing less than momentous. The massive project holds the potential for a new renaissance in commerce, industry, discovery, thought, invention, and culture that could well rival the original Silk Road. It is also becoming clearer by the day that geopolitical conflicts over the project could lead to a new cold war between East and West for dominance in Eurasia. The outcome is far from certain. (“New Silk Road Could Change Global Economics Forever”, Robert Berke, in Oil Price).

The Future Is China

Xi Jinping’s “signature infrastructure project” is reshaping trade relations across Central Asia and around the world. The BRI will eventually include more than 150 countries and a myriad of international organizations. It is, without question, the largest infrastructure and investment project in history which will include 65% of the world’s population and 40% of global GDP. The improvements to road, rail and sea routes will vastly increase connectivity, lower shipping costs, boost productivity, and enhance widespread prosperity. The Belt and Road is China’s attempt to replace the crumbling post-WW2 “rules-based” order with a system that respects the sovereignty of nations, rejects unilateralism, and relies on market-based principles to affect a more equitable distribution of wealth.

The BRI is China’s blueprint for a New World Order. It is the face of 21st century capitalism and it is bound to shift the locus of global power eastward to Beijing which is set to become the de facto center of world.

This article was originally published in The Unz Review.

Michael Whitney is a renowned geopolitical and social analyst based in Washington State. He initiated his career as an independent citizen-journalist in 2002 with a commitment to honest journalism, social justice and World peace.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

(All images in this article are from TUR and csloh.substack.com unless otherwise stated.)

Related Readings

World Bank, 2022, Lifting 800-million out of poverty

STORM, 2023 Fractionalisation in Deglobalisation

Firestorms, 2023, China socialism US capitalism

The reason that China’s overall investment could remain high is the large size of China’s state sector. Whereas U.S.A. in 2022 only 16%, less than one sixth, of U.S. fixed investment was in the state sector, accounting for only 3.4% of GDP.

Indeed, to offset a 10% decline in private investment, U.S. state investment would have to pump up by 50%.

Thus, China’s large state sector has a powerful ecosystem mechanism in keeping her ICOR down and maintaining a high level of investment – and economic growth – with dynamic efficiency.